Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

Listen to the Trust Your Voice Podcast for an audio version of this brief.

Watch The Policy Circle’s Conversation with Education Trailblazer Ian Rowe

Why it Matters

A quality education provides the foundation upon which one can build a productive life. Yet, based on recent evaluations, U.S. education lags behind other developed nations and declined in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic. The latest 2023 report from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), otherwise known as the Nation’s Report Card,” revealed the “single largest drop in math in 50 years and no signs of academic recovery following the disruptions of the pandemic.“

Prior to the pandemic, studies of American students indicate little improvement in education over the last several decades, even though spending continues to increase.

Through education, students obtain a breadth of knowledge and learn fundamental skills for critical thinking, future learning, employment, independence, and the confidence to accomplish their dreams. A quality education provides opportunities to learn about the world and opens doors to determining and fulfilling dreams and ambitions, enabling individuals to establish themselves and contribute to society.

Putting it in Context

History

George Washington proposed the U.S.’s first public education system as he left office in 1796 “to grow the country economically, but also to create a well-informed populace to participate in America’s newly founded democracy.” In the 17th century, New England colonies and townships first established mostly religious-based schools, which evolved to primarily teach elite children how to read and write. The general public’s education depended almost entirely on families, communities, and churches.

The earliest form of what we now understand as “public schools” were called Common Schools. These schools were parent-funded by tuition and housed students of all ages – as young as five to adults – in one room with one teacher and sparse materials. With rapid population growth and mass immigration in the late 1800-early 1900s, public education became a way to provide social integration, English learning, and a shared experience among children from a variety of backgrounds in addition to academics. By the mid-19th century, education became almost entirely a public endeavor. A systematic structure for education truly began to take shape when schools became more publicly available and the federal government created the Department of Education in 1867. The purpose of the agency remains the same today: to collect information on educational outcomes and teaching, and to assist states in providing effective education systems. Federal aid to states periodically increased throughout the 20th century to include vocational education in agriculture and industry, and a surge in scientific, mathematical, and technical fields for national defense.

By the Numbers

The National Center for Education Statistics(NCES) report from 2019-2020 indicates U.S. schools number just under 130,000:

Public schools: 98,469

Pre-kindergarten, elementary, and middle: 70,039

Secondary and high school: 23,529

Other: 4,901

Private Schools: 30,492

Pre-kindergarten, elementary, and middle: 18,870

Secondary and high school: 3,626

Other: 7,996

NCES reports that pre-k through grade 12 public school enrollment in the fall of 2021 totaled approximately 49.5 million, and 4.7 million students attend private schools.

As of the 2020-2021 school year, public schools employ approximately 3,032,471 teachers, while private schools employ about half a million teachers.

Women make up just over 75% of all public and private school teachers. In public schools particularly, women comprise 89% of elementary school teachers, 72% of middle school teachers, and 60% of high school teachers.

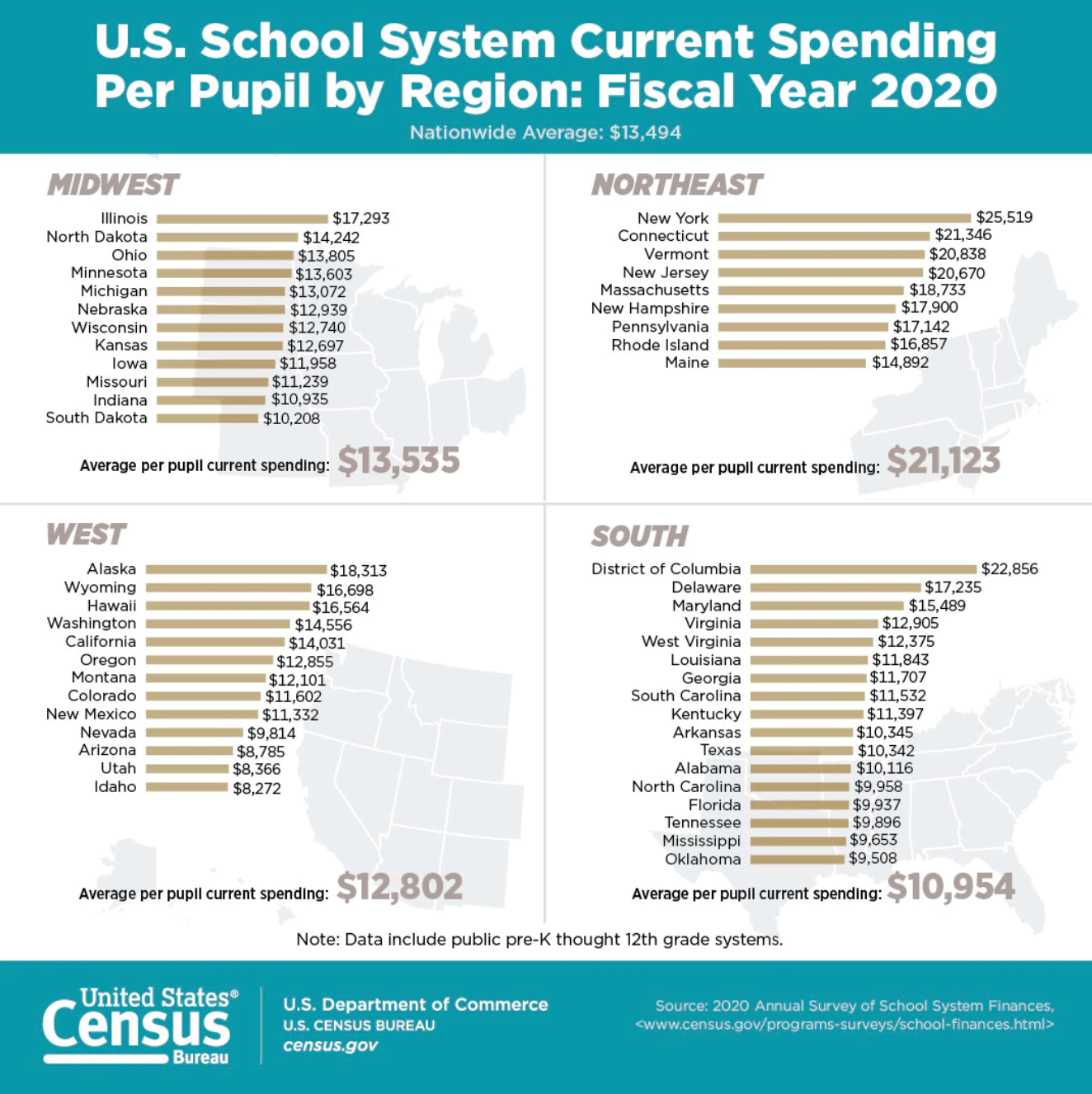

Over $751 billion was spent on public K-12 education across local, state, and federal levels for the 2020 fiscal year. Here’s a regional look. Per pupil expenditures, also known as PPE, averaged $13,200 per student nationwide.

Role of Government

Federal

The U.S. Constitution does not directly address education. The 10th Amendment states:

“The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

In plain terms, this amendment limits the federal government only to the powers provided by the Constitution and gives states, and thereby the people, the power to govern themselves. The real beauty of this amendment is that our founding fathers sought to ensure State autonomy.

How does this work in education? First, the federal government passes legislation. In turn, the federal agency establishes regulations to implement the legislation, states determine their own laws and regulations, and, finally, local education agencies (school districts) establish policies to implement state laws and regulations.

Legislation

Presently, the mission of the U.S. Department of Education is to promote “educational excellence and equal access” and provide a portion of monetary support to states. The U.S.’s very first piece of education legislation was the National Defense Education Act (NDEA) passed by Congress in 1958 to provide monetary support for schools to boost American competition with the Soviet Union” in response to the Soviet launch of Sputnik.

The next decade brought significant change to legislation addressing education in the U.S. and widely addressed equal access for all students. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 expressly provides protections against discrimination in public education on the basis of race, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 prohibits discrimination on the basis of gender, and the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (specifically Section 504) expressly provides protections against discrimination against individuals with disabilities.

Not only were these three pieces of legislation pivotal in providing protections against discrimination, but they also prohibit discrimination by recipients of federal funds. Quite simply, any state or local education agency that receives federal funds is prohibited from discriminating against students on the basis of race, sex, or disability.

Additionally, the 1965 Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) provides federal grants to improve the overall quality of elementary and secondary education. Title I of the ESEA is a program that provides federal aid to local education agencies and schools with high percentages of low-income children. The funds are intended to help schools with additional resources to provide all children meet state academic standards.

In 2002, the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) updated the ESEA and increased school accountability to educate disadvantaged students to the federal government. The law required states to test all K-12 students to indicate educational progress or lack thereof and linked federal funds based on test results.

In 2015, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) reauthorized the ESEA, replacing NCLB but maintaining the federal government’s requirements for schools to continually work to improve educational outcomes for disadvantaged students. The improved ESSA offered new grants and funding for schools to provide more support to districts, schools, and resources for teachers to work towards the goal of a “full educational opportunity” for all students.

Spending

Federal money flows to states primarily through grants designed to minimize funding gaps. These grants rely on formulas that consider the needs of each state, the average cost of education for students, and estimated poverty data from the Census. For this reason, some states receive more than others; Alaska, Mississippi, South Dakota, and New Mexico all received at least 13% of their revenue from the federal government in 2019, while New Jersey, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New York received less than 5% of their revenue from the federal government.

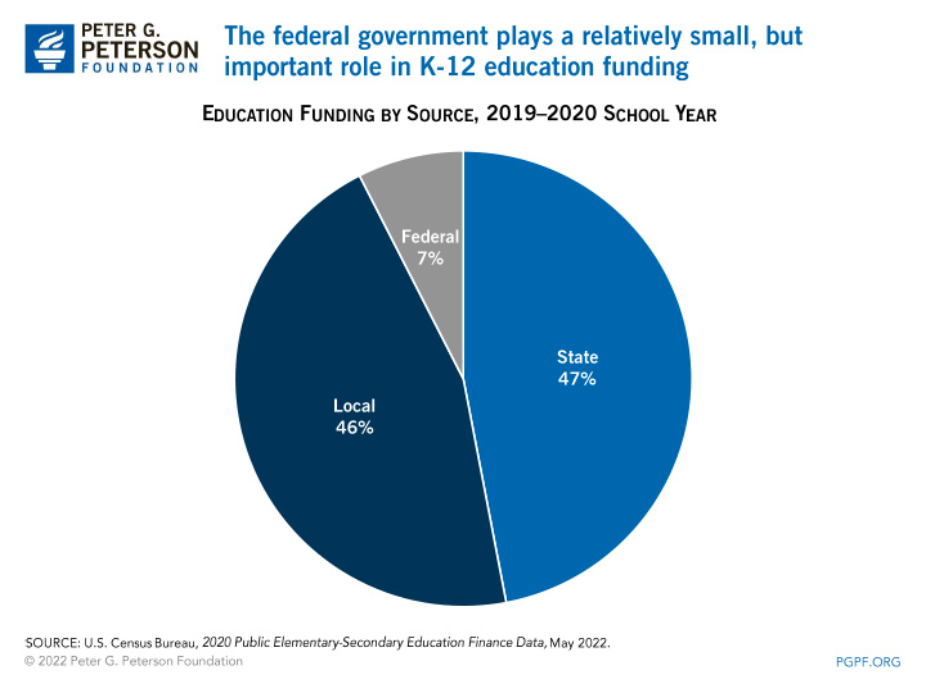

According to recent data, of the roughly $771.1 billion in expenditures for public elementary and secondary schools during the 2019-2020 school year, only 8% came from the federal government. This includes contributions from the U.S. Department of Education and other federal agencies including the Department of Health and Human Services (which runs the Head Start program) and the Department of Agriculture (which runs the School Lunch program). The majority of federal funding usually comes in the form of Title I funds, special education programs, and child nutrition programs.

Another important source of federal funding is supplemental funds for K-12 schools to educate children with disabilities. The Individuals with Disabilities Act, specifically Part B, stipulates the U.S. government will assist states in the endeavor to provide special education and related services to ensure children with disabilities receive a free and appropriate public education, also called FAPE. In the 2020-2021 school year, the U.S. provided $11.6 billion to states for the purpose of educating 7.2 million (15% of the total) children enrolled in special education. The majority of the responsibility falls to the states, as outlined above.

State and Local

The Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment requires states to provide each child equal access to public education. Children are assigned to the nearest public schools based on where they live, also known as zoning. There are just under 50 million students attending 91,328 public schools in 13,452 school districts in the U.S. See a full list here.

At the local level, school districts are “governed by multiple-member boards that oversee school district policies, finances, superintendents, and collective bargaining agreements with teachers and other staff.” At the state level, each state has a department or agency that oversees elementary and secondary public education. An elected or appointed state executive, usually referred to as the superintendent of schools or chief school administrator, heads the department. At both the state and local levels, school board members are either elected or appointed by mayors or governors. School boards share authority with local government or state departments of education. See The Policy Circle’s Understanding School Boards Engagement Guide for more on this topic.

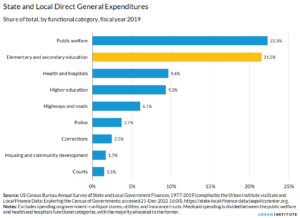

State legislators set state budgets and use funding formulas to determine how much each school district will receive from the state. Each state’s funding formula is meant “to diminish somewhat the high degree of inequality in revenues per pupil that would result if funding were based only on local taxable resources and the willingness of local citizens to tax themselves,” and thus “provide at least some limited degree of ‘equalization’ of spending and resources” for all districts across the state. The state applies funding towards operations (e.g. salaries and benefits for teaching, guidance counseling, materials like textbooks, transportation, and facilities like libraries) as well as maintenance and construction of public schools.

State and local funding are almost equal to a national average, with state governments providing around 47% of revenue and local governments providing about 45%. But individual state shares vary widely; Hawaii has no local educational agencies, so almost 90% of funding comes from the state. On the other hand, the District of Columbia has no state government, so almost 90% of its revenue comes from local sources. You can see your state’s distribution in this Congressional Research Service Report (last updated 2019).

Revenues are raised mainly from taxes; state revenues mostly come from income and sales taxes, while property taxes generate local revenue.

Challenges and Areas for Reform

Spending and Outcomes

According to data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), total public elementary and secondary school spending amounted to $800 billion for the 2018-2019 school year). Per-pupil spending increased every year since 2015. The largest increase of 5% occurred during the 2019-2020 school year in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

“Money can matter, but spending more on schools does not yield big improvements,” explains Mark Dynarski of Brookings Institution. Despite overall spending increases, the “Nation’s Report Card” from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) reveals there has been little improvement in student performance since 2011. A 2019 report from Michigan State University analyzing long-term education spending trends found that, based on the NAEP scores, “there was no clear correlation between spending increases and test improvements from 2003-2015.” According to the latest NAEP results as of June 2023, students scores in reading and math plunged.

U.S. student performance amidst higher spending has remained stagnant at an international level as well. In 2018, the U.S. average spending per K-12 student ($14,400, including capital expenditures) was 34% higher than the average spending for Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries ($10,800). Despite the spending differences, results from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), which measures performance in reading, math, and science among 15-year-olds in dozens of countries every three years, show U.S. scores have not significantly changed since the early 2000s. The most recent PISA results, from 2018, placed the U.S. 13th in reading, 37th in math, and 17th in science out of 77 education systems.

Evidence that indicates how money is spent, rather than how much money is spent, plays an important role in the conversation about funding for public schools. Students in predominantly low-income districts often have the greatest need for educational services and resources. A 2018 report from the Education Trust compared the most recent data on educational spending and found that even if governments could decrease the per pupil spending gap with additional funds, the issue of equitable spending was still significant; meaning additional funds did not quite close the gap between available resources to schools, teachers, and, ultimately, students.

How does this influence educational outcomes?

Preliminary data suggest a link between state education finance reforms and higher test scores among students, higher rates of high school graduation, and better earnings among graduates. State education finance reforms typically increase overall spending and specifically increase spending in low-income districts relative to high-income districts. Because some reforms are not temporary increases, they allow lower-income schools to make long-term investments. Finance reforms have been shown to reduce achievement gaps between high- and low-income school districts. A National Bureau of Economic Research paper found “significant gains for students in poorer school districts in the wake of court-ordered state funding increases.” However, if either temporary or long-term finance reforms do not address or provide improvements to resources, curricula, and teacher development, the increase in outcomes is short-term.

Many education policy leaders, parents, and advocates are now increasingly raising concerns about how school funding is really being spent and where money is allocated. The national conversation about education, teachers, and funding has gained traction in the last couple of years as the country returns to pre-COVID conditions and outcomes are reported.

Literacy is one of the most impactful areas of education. Explore how spending and other factors that impact education influence literacy in our brief: Failing Grade: Literacy in America

Teachers

According to reports from state education agencies to NCES, the projected number of public school teachers is 3,032,471 in 2021, which puts the student/teacher ratio at 15.4. This is a 17% drop from 3,679,000 public school teachers in 2019.

Each state requires its own qualifications to teach in K-12 schools; a teaching certificate, a bachelor’s degree, state licensure, or advanced degrees depending on the subject or “assignment” taught. At a minimum, states require individuals to become certified in the state to teach. The U.S. Department of Education indicates states are required to report teacher qualifications to the federal government to ensure qualified individuals teach students and that the state distributes qualified teachers equally. Information regarding teacher qualifications is “public information” which means the public has access to some, but not all, personnel records of district employees. The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) protects the information. If you are curious about your child’s educator, contact your state or school district administration to inquire.

Teachers’ pay is determined by qualifications, undergraduate and postgraduate degrees, advanced certifications, and experience. A public school teacher’s total earned income in 2018 was $62,200, while a private school teacher’s salary started at $50,340. Salary estimates for the 2020-2021 school year put public school teachers at $65,090. Teacher pay fluctuates between states and even between neighboring school districts. See what your state pays teachers here.

In his 2017 study, “Back to the Staffing Surge,” Professor Ben Scafidi notes that “the productivity of American public schools has fallen rather dramatically over the past few decades. And, in retrospect, the staffing surge in American public schools has appeared to have been a costly failure.”

This video synopsis explains further (8 min):

Quality

Teacher quality matters when it comes to student outcomes. Hoover Institute Senior Fellow Eric Hanushek commentson a 2012 article “Great Teaching” that the “evidence shows that bad teachers cost hundreds of thousands of dollars in lost income and productivity each year that they remain in the classroom.” According to a University of Melbourne review of over 65,000 papers exploring the effects of various classroom interventions, “‘[a]ll of the 20 most powerful ways to improve school-time learning identified by the study depended on what a teacher did in the classroom.’”

PolicyEd explains why investing in good teachers pays off (1 min):

Since teachers must obtain minimum qualifications to teach K-12, which determines salaries coupled with experience, many seek to advance their qualifications.

The U.S. Department of Education’s TEACH Grant Program offers up to $4,000 yearly to students who plan to become teachers who agree to serve four (4) years teaching in a high-need teaching field and underserved school. Another federal program offered by the DOE is the Teacher Quality Programs (TQP) which aims to “improve our nation’s schools and student achievement” by supporting state efforts to improve and retain quality teachers and principals and encouraging local education agencies to partner with communities and postsecondary schools.

Similarly, the National Education Association (NEA), one of the two main teacher unions in the nation (discussed below) offers grants to teachers for professional development and prospective teachers to aid in the costs associated with obtaining state licensure or certification.

Teach For America is a program that finds educational leaders and offers extensive leadership courses and opportunities to enhance their understanding of the needs of underserved populations. The program requires members to teach low-income students in a public school setting for at least two years with the goal of partnering with the community to better meet the needs of the students.

In the 2021 fiscal year, the federal government appropriated $5,571,845 for the National Professional Development Program which aims to improve instruction for English Learners.

Unions

Teacher unions originated as local associations and “grassroots efforts to support teachers through improved salaries, benefits, and working conditions.” The two largest unions, the National Education Association (NEA) and the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) were first organized in 1857 and 1916, respectively, to represent the interests of the profession and improve salaries and working conditions for teachers. Now, almost 70% of all public school teachers affiliate with teachers’ unions or an employee association.

As education reform gains traction nationwide, teachers’ unions are seen “either as the major hurdle standing in the way of true reform, or a potentially valuable tool in bringing about the sort of change needed in education today.”

Whether teachers’ unions’ effect is positive or negative remains a key debate in education reform. A 2018 study from the University of Michigan found that “states with stronger unions saw more of the money earmarked for education actually reach the classrooms” or used for teacher compensation; whereas states with weak unions saw funding for schools being used to cut local property taxes.

Unions acquire funding through donations, dues, and fees paid by members and non-members who stand to benefit from union efforts. Political spending and endorsements by teacher unions is an area of debate. . A Pennsylvania-based education policy organization, the Commonwealth Foundation, reported the NEA spent roughly $45 million on political activities in 2016-2017.

Unions faced considerable scrutiny over their resistance to returning students to in-person learning in some states in the fall of 2020 and 2021. Forbes reports private and religious-based schools found creative ways to get their students learning again, which public school districts could have, but failed to, model to deliver students similar learning and instructional opportunities.

Compensation

What was once occasional news, teacher strikes made headlines at the beginning of the 2022-2023 school year. The strikes bring attention to the issue of teacher pay, as it has in previous years, but additional federal funds in response to the COVID-19 pandemic spurred additional requests by teacher unions. Teachers in Columbus, Ohio went on strike for the first time since 1975 over salaries, classrooms, building conditions, student-to-teacher ratios, and resources, among other issues.

According to NCES data from 2016, 16% of public elementary and secondary school teachers have summer jobs and 6% have second jobs during the school year, which makes up 5-10% of their annual income. See this Business Insider report for a state-by-state ranking accounting for salary.

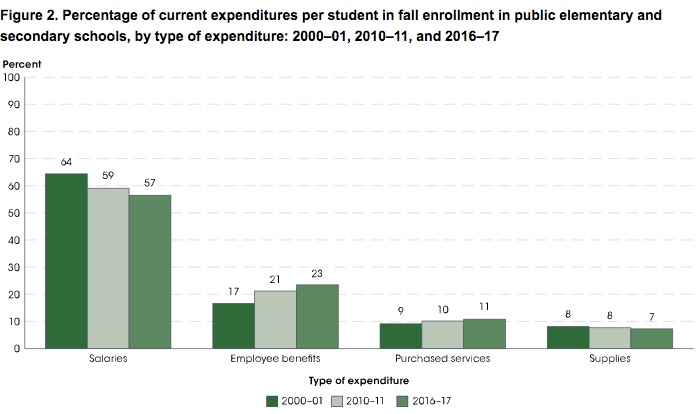

Real spending on education has increased by almost 40% since the 1990s, but teachers have seen little of this in their salaries. Per pupil spending increased between 1992 and 2014 by 27%, but teacher salaries decreased by 2% over that same period. Education scholar Frederick Hess calculated teacher salaries in West Virginia would have increased by more than $17,000 since the early 1990s if salaries had increased at the same rate as per-pupil spending.

On the other hand, substantial retirement and healthcare benefits make total teacher compensation higher than average salaries indicate. Public school teachers receive over $6 per hour in retirement compensation; the average civilian employee receives less than $2 per hour in retirement benefits. However, in some cases where school funding has gone up, payments go to paying down pension debt rather than funding better benefits for current teachers. According to Chad Adleman of Bellwether Education Partners, teacher salaries in Kentucky would be $11,400 higher “if the state wasn’t forced to spend vast sums paying down pension debt.” Paying for existing obligations remains a challenge that many states have yet to figure out.

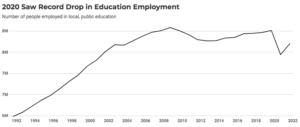

The teacher strikes that were common in 2018 and 2019 had a lull during the coronavirus pandemic, during which time teachers had to manage “unprecedented classroom concerns, such as masking, vaccinations, remote learning, and hybrid learning,” and found themselves “on the front lines of a mental health crisis among adolescents who also incurred significant academic losses due to remote learning[.]” These demands and pressures have left many teachers citing burnout. In 2020, there was a record drop in public education employment, and in 2022 strikes restarted in cities from Minneapolis to Chicago to Sacramento.

Some states and districts are considering using leftover funds from the American Rescue Plan to offer raises and signing bonuses, but whether these incentives can spark long-term change and offset problems in the education system that have been growing for years remains to be seen. For example, staffing shortages are not new; student loan debt has increased, and many college graduates tend to select careers that pay more than teaching.

Education Choice

Another component of education reform debates centers around school choice. Some argue that families should be able to access the best school for their child, particularly among low-income or minority student groups, or students with specific educational needs such as autism or physical needs such as cerebral palsy. Advocates argue that if parents can choose the school that is best for their child, it can generate better quality educational options and promote greater access to higher quality or more specifically designed education.

This report maintains that the public school system is designed to provide an equal education for all students to promote an equal, standardized education in the U.S.’s economic prosperity, funded by taxpayer dollars. As determined earlier in this brief, public schools are funded by the number of students who attend them; therefore, funding streams diminish if students seek an education outside the public education system.

Recently, religious-based schools have received harsh criticism for taking federal funds but failing to provide a basic education to students. Students interviewed for the article stated they “graduated” from one of these schools but still had to teach themselves how to read and write. NYC Mayor Eric Adams called for an independent investigation. Here’s the link for the New York Times investigation.

Some are concerned that school choice may negatively affect public schools by taking students and funding away from struggling district schools, or those lower-income families with few additional resources will not be able to take advantage of school choice options.

The latest polling and report from Edchoice.org also showcases continued support for school choice policies from both school parents and the general public alike.

School Choice Week further breaks down the types of schools in K-12 Education (2 min):

Vouchers

According to Edchoice.org, “School vouchers give parents the freedom to choose a private school for their children, using all or part of the public funding set aside for their children’s education. Under such a program, funds typically spent by a school district would be allocated to a participating family in the form of a voucher to pay partial or full tuition for their child’s private school, including both religious and non-religious options.”

There are 29 voucher programs operating in 16 states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico, of which just under 250,000 students are recipients.

Tax Credit Scholarships

Tax credit scholarships “allow taxpayers to receive full or partial tax credits when they donate to nonprofits that provide private school scholarships. Eligible taxpayers can include both individuals and businesses. In some states, scholarship-giving nonprofits also provide innovation grants to public schools and/or transportation assistance to students choosing alternative public schools.”

There are 26 tax credit scholarship programs in 21 states, of which just under 330,000 students are recipients.

Education Savings Account (ESA)

Education Savings Accounts (ESAs) are a more recent innovation in parent choice programs that “allow parents to withdraw their children from public district or charter schools and receive a deposit of public funds into government-authorized savings accounts with restricted, but multiple uses such as private school tuition or outside educational services.”

ESAs gained attention due to the coronavirus pandemic when Congress proposed the Education Freedom Scholarships and Opportunity Act (EFS). Through an annual federal tax credit for businesses and individuals who donate to certain certified organizations, funds would pay for K-12 education options such as private school tuition, private tutoring, online classes, instructional materials for home education, and even after-school or daycare programs. In the short term, EFS serves as a means of providing emergency assistance to students and their families. The California Policy Center, for example, notes parents have been investigating options such as virtual schools, homeschooling, and private schools. Others argue this would undermine public schools that are struggling and facing budget cuts amidst the pandemic. Conversely, educational innovation has been a positive result of the COVID-19 pandemic as parents explore alternative, and possibly more appropriate, options outside of the public school system, and districts must now compete.

For more on ESAs and EFS, see The Policy Circle’s Education Savings Accounts Brief, or watch The Policy Circle’s Virtual Circle Discussion (46 min):

For a deeper exploration into School Choice listen to Sylvie Legeré’s Podcast Episode: Hostages No More with Guest Former US Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos.

For what school choice options exist in your state, see the National Conference of State Legislature’s guide.

Vocational Schools

Vocational and career and technical education (CTE) is “‘organized education programs offering a sequence of courses which are directly related to the preparation of individuals in paid or unpaid employment.’” This avenue of career training provided students with labor market skills while preparing them for jobs in technical fields.

In the 1980s, there was a shift away from vocational and CTE classes as schools increased academic requirements for students. In an effort to push high school graduates to apply to college, vocational and CTE classes were dismissed by claims that vocational training in high school would lead to “dead end jobs.” Conversely, some high school graduates likely will not succeed in college and seek gainful employment in a vocational skill or trade after graduation. This argument, combined with the reality of worker shortages in skilled professions, led to increased attention towards vocational and CTE training as the potential difference between high- and low-paying jobs for many students. In 2018, legislators proposed over 250 CTE-related bills in 42 states, mostly to increase state funding for programs, and the numbers have only increased since.

The development of regional vocational and technical high schools, entire schools devoted to vocational and career-oriented instruction, also indicates vocational training is viewed as more than just auto mechanics. Today, it “encompasses everything from welding, to sports management, to computer science.” Programs such as P-Tech, a partnership with IBM, and other programs incorporate dual enrollment opportunities with local community colleges or apprenticeships. Engaging with local businesses can also ensure students are getting skills that lead to employment, especially in a local job market. For more on CTE and vocational training, see The Policy Circle’s Creating Career Pathways Brief.

Gaps

Early Childhood Education

Research is fairly clear that high-quality early childhood education is an important part of student success. Longitudinal studies find that “those who participated in these early childhood educational interventions persist in education, have higher earnings and commit fewer crimes than the control group.”

Some studies of government-funded preschool programs, such as Head Start, have found evidence of “fadeout,” which indicates that higher test scores early on fade as they move into grade school. While other studies show the programs work “particularly for students who otherwise would not be in center-based care.” According to the RAND Corp., in preliminary assessments, “researchers found that returns of $2 to $4 were typical for every dollar invested in early childhood programs,” on top of social benefits such as school readiness that continue into adulthood.

Summer Learning Loss

“Summer learning loss” describes scores that decline over the summer, which results in students starting the year behind where they should be. According to a Brookings report, studies found on average, “students’ achievement scores declined over summer vacation by one month’s worth of school-year learning.”

This disproportionally particularly affects low-income students based on the “faucet theory,” that all students have access to resources during the school year, but the flow of resources slows or stops for students from low-income backgrounds.

Summer vacation can be important to help students retain, or even master, academic skills. Professor Paul T. von Hipper of the University of Texas at Austin claims “every summer offers children who are behind a chance to catch up.” However, summer program coordinators have trouble attracting high-quality teachers as well as appealing to students and families to participate. Program costs are another dilemma, especially for low-income students. Professors David Quinn and Morgan Polikoff of the University of Southern California suggest that lower-cost home-based summer programming can still positively affect learning outcomes. Additionally, when extensive school-based options are infeasible, districts can pursue more cost-effective strategies such as targeted interventions for “students most at risk of backsliding.”

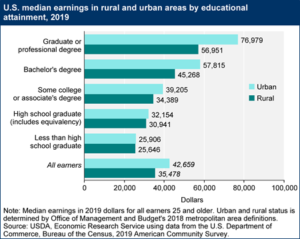

Geography

“The educational attainment of people living in rural (nonmetropolitan) areas has increased markedly over time but has not kept pace with urban (metropolitan) gains,” says the U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. Low populations of students and difficulty recruiting teachers present a challenge in rural areas. On the opposite end of the spectrum, inner cities and urban districts also face staffing and funding shortages. Problems associated with urban poverty, including housing, food insecurity, high dropout rates, criminal justice system involvement, and high proportions of students whose first language is not English, also pose challenges to educators in inner cities.

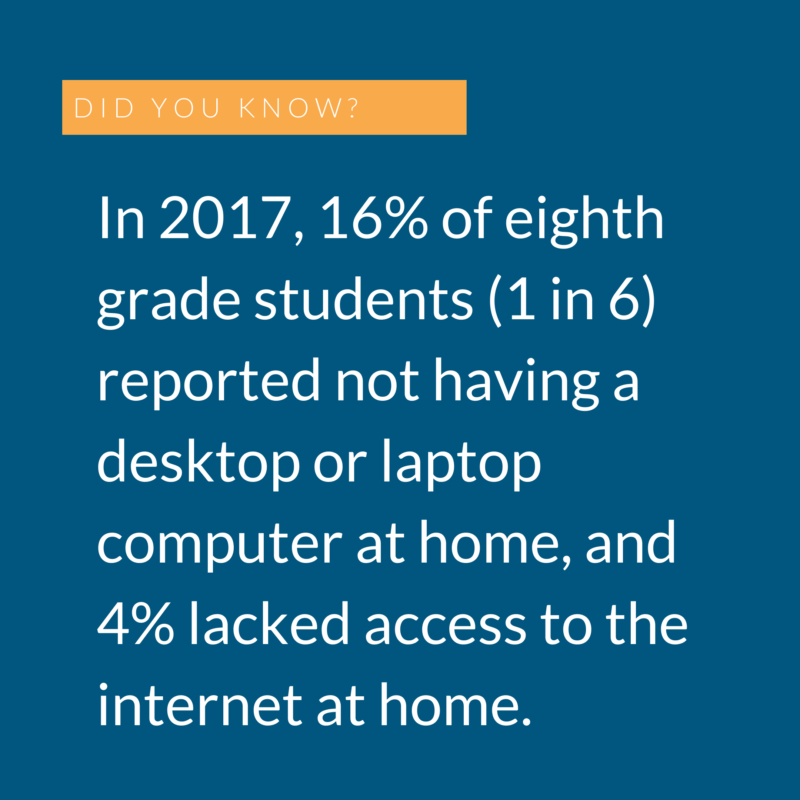

Online Learning & The Digital Divide

Online education can be a cost-effective means to fill gaps and offer more course choices and access, but the quality of online schools varies greatly. Additionally, the issue of the “digital divide,” that not all households have access to reliable high-speed internet, presents a problem for many students. See The Policy Circle’s Digital Landscape Brief for more on the digital divide.

The problem has become even more prominent due to the coronavirus pandemic. A poll in California at the beginning of the pandemic revealed 50% of low-income families said they lack sufficient devices to access distance learning at home. Nationally, principals in the highest-poverty schools reported a full 20% of students did not have adequate access to internet services at home.

Online learning also requires technology proficiency for teachers and access to resources necessary to teach and virtually engage students. A RAND analysis of the American Educator Panel’s Fall 2020 COVID-19 Surveys found 80% of teachers reported feelings of burnout since the start of the pandemic, and two-thirds reported they did not receive adequate guidance on how to support students. Resources that support teachers can help them best implement personalized learning through flexible approaches and interventions for students at risk of falling behind or dropping out.

Detailed assessments of each school in the district can help identify what stressors impact the ability of children to learn, which, in turn, will help determine what resources can be leveraged to meet students’ needs. Understanding the needs of students, families, and communities can open avenues of communication with local philanthropic organizations, utility and technology providers, and businesses for public-private partnerships.

Professor Paul Reville of Harvard’s Graduate School of Education suggests taking advantage of youth-serving organizations and institutions to form “children’s cabinets,” which can “bring together community members, government officials, business leaders, parent organizations, and student organizations to develop strategies to better student outcomes.” For example, school buses outfitted with Wi-Fi were used as hotspots in South Carolina; Staples in Tennessee began printing materials free of charge for students who could not afford it; and partnerships with Comcast brought free internet to students in school districts including Caldo Parish, Louisiana, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

The Coronavirus & The Future of Schools

Coronavirus-induced school closures in 188 countries affected 1.7 billion children and their families. In the U.S. alone, 55 million children under the age of 18 were learning from home in the spring of 2020. In 2022, even as schools reopened, a considerable number of parents chose to homeschool their children. Across 18 states that shared data, the number of homeschooled students increased by 63% in the 2020-2021 school year, then fell by 17% in 2021-2022. Before the pandemic, only about 3% (2 million students) were homeschooled, which did not prompt much consideration from governments. For example, there are no federal guidelines for homeschooling resulting in little uniformity. Connecticut and Nevada require little to no information from parents, while New York and Massachusetts require instruction plans and assessments. How state legislatures proceed, and whether this trend will decrease over time, remains to be seen.

even as schools reopened, a considerable number of parents chose to homeschool their children. Across 18 states that shared data, the number of homeschooled students increased by 63% in the 2020-2021 school year, then fell by 17% in 2021-2022. Before the pandemic, only about 3% (2 million students) were homeschooled, which did not prompt much consideration from governments. For example, there are no federal guidelines for homeschooling resulting in little uniformity. Connecticut and Nevada require little to no information from parents, while New York and Massachusetts require instruction plans and assessments. How state legislatures proceed, and whether this trend will decrease over time, remains to be seen.

While some believe the negative side effects of learning disruptions will fade by the time students complete their education, the abrupt shutdowns brought to the forefront “needs which have been so glaringly exposed in this crisis,” ranging from food deficits and inadequate access to health and mental health resources to housing instability and inadequate access to educational technology and internet services. The resource-based advantages and disadvantages between students will likely affect the extent to which K-12 students experience learning loss.

The most recently reported findings by NCES in The Nation’s Report Card compared learning in 2020 to 2022. The study indicates decreases in math and reading scores in all student categories, high- and low-performing students alike.

Congressional relief aid for K-12 schools came in the form of the $2 trillion stimulus package (CARES Act) in March 2021, which included $13.2 billion for K-12 schools. Calls for action at the federal level continue, as states and school districts “are not only overstrained but also facing imminent budget cuts caused by the pandemic, with an inability to incur deficit spending.” The federal spending bill passed in March 2022 increased public school spending by $2 billion over 2021 funding levels.

According to the State Policy Network, a significant weakness in the education system is that it is “built for one approach and a single learning style,” causing the pivot to virtual learning all the more difficult for schools, teachers, and students. Emma García, an education economist at the Economic Policy Institute, highlights the limitations of standardized testing, especially in a virtual learning environment. Assessments besides standardized tests tailored towards online learning or representative of various learning styles, such as diagnostic tests, project-based assessments, or capstone projects, can better measure students’ progress.

Finally, schools play essential roles in non-academic areas. The CARES Act touched upon this with over $25 billion for SNAP and child nutrition programs, as well as a key provision that gave school districts greater flexibility in providing meals to students and their families. This provision, which Congress extended through September 2021, allowed schools to use summer rules when distributing food, allowing families to pick up food at community locations. Still, one study reported that just over 60% of families who were supposed to receive free or reduced-price meals during the school year received meal assistance during school closures.

The Economic Policy Institute takes this one step further and recommends “institutions that create education policy and practice must make many changes to ensure that schools teach and reward the development of cognitive and socioemotional skills,” rather than only academic skills. Brookings Institution’s Emiliana Vegas, EdD, argues for “teaching students transferable skills, including creativity, problem-solving, and analytical thinking.” The March 2022 federal spending bill includes $1.2 billion in grants supporting school safety and student health.

Conclusion

Over the past few decades, increases in educational spending have not led to improved educational outcomes, nor have they closed achievement gaps. Students, teachers, and schools face complicated dilemmas – from food insecurity to the digital divide – all of which were exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic. Providing students, parents, and teachers with the necessary resources and flexibility is key to the U.S. education system’s ability to best prepare young people for successful careers beyond school and far into adulthood.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Find out what your state and district are doing about K-12 education.

- Do you know the state of K-12 education in your community or state?

- Do you know how your district’s public school ranks? Are there private or vocational options?

- Are there afterschool programs to engage children, or local organizations dedicated to this?

- Do you know your school district’s budget? How are teachers compensated while they teach and after retirement?

- What are your state’s laws on school choice?

- Does your state offer tax credit or similar scholarships?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Who are the members of the school board in your community? Who is your state’s superintendent of schools?

- Who is your school district’s superintendent, and who are the principals?

- What steps have your state’s or community’s elected or appointed officials taken in terms of education?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with community organizations, school boards, or local businesses.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, communications@thepolicycircle.org, for connections to the broader network, advice, and insights on how to build rapport with policymakers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Meet with a family who chooses private or charter schools as an option for educating their children, and ask their views.

- Volunteer at your child’s school to learn how the school runs and how decisions are made.

- Volunteer as a mentor or tutor for an organization or support an after-school program, maybe by sharing your own professional talents such as cooking or gardening.

- Ask to meet with a school board member, or attend school board meetings to ask questions, find out about priorities, and review annual budgets.

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.

Thought Leaders and Additional Resources

Thought Leaders and Organizations

- Economist Roland Fryer, founder and faculty director of the Education Innovation Laboratory at Harvard University on why he was drawn to education reform and why accidents of birth should not determine our access to a high-quality education:

- Dr. Fryer was also the lead on a research project that determined the five effective habits of charter schools.

- The Education Trust is a nonprofit organization that promotes closing opportunity gaps by expanding excellence and equity in education for students of color and those from low-income families from pre-kindergarten through college.

- Foundation for Excellence in Education focuses on personalized learning, in addition to choice and accountability.

- The American Federation for Children website compiles data on parent choice programs available across various states in an easy-to-use map format.

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.

Deep Dives

Want to dive deeper on Education: K-12? Consider exploring the following:

State Briefs

Want to learn more about how states are dealing with this issue? Read our state-specific briefs below: