Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

Case Study

Construction workers in North America “are roughly six times more likely than workers in other manufacturing, industrial, and service industries to become addicted to opioids.” In Massachusetts, where the construction industry employs 4% of the state’s workforce, construction workers accounted for 25% of all opioid overdose deaths between 2011 and 2015.

Construction workers tend to perform the same tasks every day, many of which require carrying heavy loads that can lead to injuries. Workers can easily turn to strong prescription drugs and develop substance use disorders.

A 2019 report of data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the National Institute of Drug Abuse noted the construction industry was less productive and saw increasing costs due to opioid use. In fact, a construction company’s yearly average healthcare cost per worker is roughly $2,900; for workers with a substance use disorder, that cost jumps to $4,700. At the same time, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce reported in its 2020 fourth quarter survey that 40% of contractors had to turn down work because of difficulty finding workers.

“Many contractors deal with the issue by putting naloxone, a drug that can revive overdosed users, on site, a sign they are focused on short-term fixes for a long-term health crisis.” Some industry groups and unions, however, are looking for long-term solutions, such as creating education materials for companies to teach workers, like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s Sharing Solutions Project. Others are working on their own programs to provide treatment, counseling, education, and recovery support.

Why it Matters

As a declared national crisis, the opioid epidemic is not an individual problem; it affects society as a whole, hindering economic growth and draining the healthcare system. Americans directly suffering substance use disorders experience the most upheaval in their day-to-day lives, as they may also deal with mental health problems, homelessness, issues finding or keeping a job, and financial strains. By extension, friends, family, coworkers, employers, health practitioners, and emergency responders are also impacted by addiction.

Putting it in Context

History

The history of opiates dates back to 3400 B.C., when human societies first learned about the use of opium, a narcotic obtained from poppy. People were able to derive from opium a number of drugs with similar properties, from morphine and heroin to prescription painkillers like Vicodin and OxyContin.

Opium and its derivatives, such as morphine, are referred to as natural opioids, but there are also compounds that “act on the same targets in the brain” even though they are manufactured in a laboratory. These are referred to as synthetic opioids and include methadone and fentanyl. Opioids are particularly useful in regulating pain by interacting with the body’s reward system. “That makes opioids powerful painkillers, but also debilitatingly addictive.”

In the 1990s, pharmaceutical companies “reassured the medical community that patients would not become addicted to prescription opioid pain relievers, and healthcare providers began to prescribe them at greater rates.” In 1996, Purdue Pharma introduced OxyContin, the extended release form of oxycodone, marketing it as a “safer” form of opiate that reduced the likelihood of addiction. However, “people soon discovered that the capsules could be crushed into powder and then injected or snorted.”

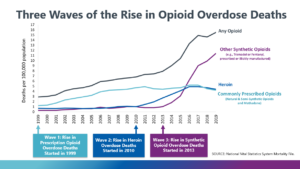

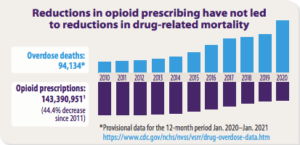

In response, Purdue developed a different capsule in 2010, one that was harder to crush, and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) issued new guidelines stipulating that doctors should try approaches such as exercise and behavioral therapy instead of opioids. Opioid prescriptions began to drop, but as they became more scarce and their street price went up, drug cartels saw an opportunity. Heroin flooded the market, followed by Illicitly manufactured synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, and people who could not afford opioids turned to these options. The chart below shows how the majority of opioid overdose deaths have changed from being principally from prescription opioids to heroin and synthetic opioids.

TED-ed explains more (8 min):

By the Numbers

Doses

A Washington Post investigation of the Drug Enforcement Agency’s (DEA) database that “tracks the path of every single pain pill sold in the United States” revealed three companies manufactured almost 90% of all opioids, and six companies distributed 75% of all opioids. Between 2006 and 2012 (before opioid prescriptions started to fall), these companies distributed 76 billion opioid pain pills, “enough pills to supply every adult and child in the country with 36 each year.”

Consequences

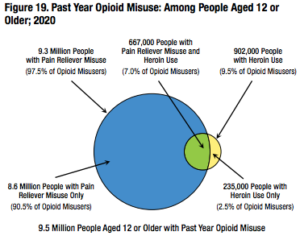

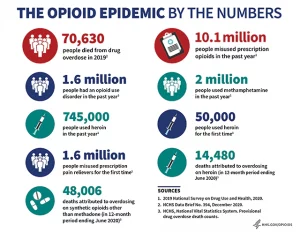

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, roughly 20-30% of patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain misuse them, and between 8-12% of those patients develop a substance use disorder. In 2020, an estimated 9.5 million people aged 12 or older misused opioids.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CD) estimates the economic burden of prescription opioid misuse, including costs of healthcare, lost productivity, addiction treatment, and criminal justice involvement, amounts to $78.5 billion annually in the U.S.

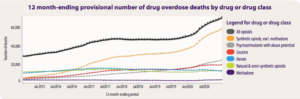

Despite a significant reduction in opioid prescriptions, there has been no corresponding reduction in drug-related deaths due to a substantial increase in illicit drugs and synthetic opioids (mainly methamphetamine, cocaine, and fentanyl).

In 2019, U.S. overdoses reached record numbers; nearly 72,000 Americans died from drug overdoses. Opioids accounted for more than two-thirds of these fatalities.

In 2020, the U.S. saw a 29% rise over this record, hitting a new record of 93,000 overdose deaths. Opioids accounted for almost three-quarters of death and fentanyl in particular was involved in more than 60% of overdose deaths.

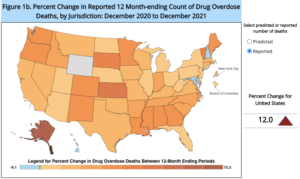

In 2021, more than 107,000 Americans died of drug overdoses, a 15% increase from 2020’s record. Deaths involving fentanyl were up another 23% over 2020. These numbers reveal that roughly one American dies of a drug overdose every 5 minutes, and that more Americans die from drug overdoses than from car accidents or gun violence.

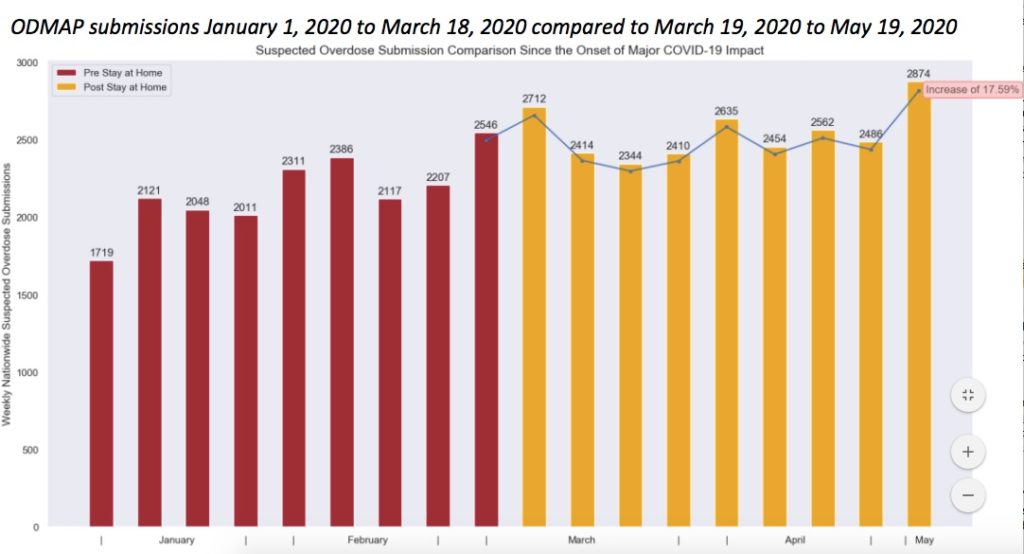

Fatalities were rising even before the coronavirus pandemic, which has only made the crisis worse; national, state, and local reports suggested overdoses increased by almost 20% after stay-at-home orders were implemented. A survey of U.S. adults in September 2020 revealed 15% of respondents had started or increased substance use to deal with stress or emotions related to the pandemic.

The Role of Government

Federal

The executive branch plays the primary role in combating the opioid epidemic at the federal level. The main coordinating federal agency is the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP). The office coordinates the federal government’s anti-drug efforts by developing a National Drug Control Strategy; funds and coordinates law enforcement and community-based initiatives; and funds and coordinates the 16 federal agencies that are involved in combating the opioid crisis.

Of these agencies, the Department of Health and Human Service (HHS) and the agencies under it – including the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) – have the biggest federal footprint in the opioid fight. The CDC’s Overdose Data to Action cooperative agreement awards funds to help support state and local health departments gather timely data about drug overdoses and use this information in prevention and response efforts. SAMHSA offers an Opioid Overdose Prevention Toolkit for community members, family members, and healthcare professionals to learn the signs and symptoms of substance use disorders. The FDA makes important drug approval and removal decisions; see a full timeline of FDA involvement with the opioid epidemic since the 1990s here.

Other actively involved agencies include:

- Customs and Border Protection and Immigration and Customs Enforcement under the Department of Homeland Security to combat drug smuggling and trafficking across international borders;

- The Office of Foreign Assets Control under the Department of the Treasury to enforce economic and trade sanctions against international narcotics traffickers;

- The Commerce Department to fight illegal and unapproved drug sales;

- The Drug Enforcement Administration and the Federal Bureau of Investigation under the Department of Justice (DOJ) to identify and stop opioid sales as they appear on the market.

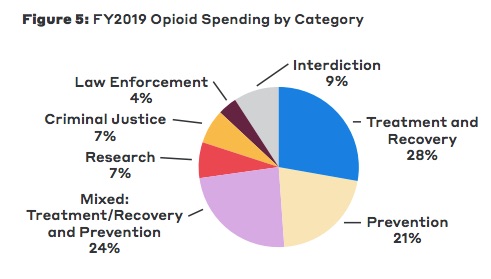

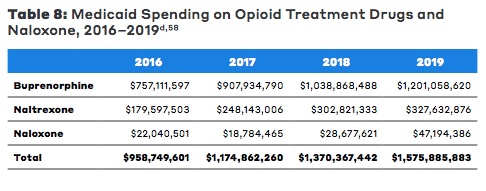

These agencies received over $35 billion to implement the nation’s drug control policies in FY2021 (Sept 2020 – Oct 2021). As estimated by the Bipartisan Policy Center, federal opioid funding may take about 20% of this total; total opioid funding amounted to $7.6 billion in FY2019. Roughly 75% went to treatment, recovery, and prevention efforts. The remaining funds went to research, law enforcement, and interdiction (disrupting trafficking). This total, however, only includes discretionary funding, and so does not include Medicaid coverage of medications used for opioid use disorders. Total Medicaid spending on these medications was estimated at $1.6 billion in 2019.

The December 2020 funding package in response to the coronavirus pandemic included $4.25 billion in mental health and substance-use emergency funding, and the March 2021 American Rescue Plan provided an additional $3.5 billion worth of block grants for mental health and substance use, targeted funding that mostly went to addiction-treatment providers and state or local agencies having to manage tighter budgets due to the economic impact of the pandemic.

The December 2020 funding package in response to the coronavirus pandemic included $4.25 billion in mental health and substance-use emergency funding, and the March 2021 American Rescue Plan provided an additional $3.5 billion worth of block grants for mental health and substance use, targeted funding that mostly went to addiction-treatment providers and state or local agencies having to manage tighter budgets due to the economic impact of the pandemic.

State

At the state level, many states are working to combat opioid addiction by expanding access to evidence-based treatment. States are working to expand treatment programs and health insurance coverage to address opioid abuse, either by expanding Medicaid or by enacting legislation. As of January 2022, 38 states had implemented policies related to setting opioid prescription limits. See Ballotpedia’s report for legislation and the National Roadmap on State-Level Efforts to End the Nation’s Drug Overdose Epidemic from the American Medical Association.

Many states have also taken it upon themselves to designate opioid task forces to oversee efforts and initiatives in combating the opioid epidemic. Designing programs at the local level instead of in Washington, D.C. allows the assistance to be tailored to fit the needs of the issues feeding addiction in each community. When it comes to federal funds, grants appear to be going to the counties with the highest number of overdose deaths, and states are required by the grants to target those resources accordingly.

See the map from the Bipartisan Policy Center for state-by-state opioid appropriation data.

The Private Sector

Although the public sector tends to spearhead the fight against the opioid epidemic, the private sector is just as involved. Businesses have a strong incentive; federal data indicates that the total number of truck and bus drivers, commercial pilots, railroad operators, and pipeline workers who failed federal drug tests increased by 77% since 2006. With a considerable number of job applicants failing pre-employment drug tests, companies are grappling with worker shortages, which affects not only individual businesses’ productivity but also economic growth of the nation as a whole. Failed drug tests that prevent employment also make it harder for Americans to get back on their feet.

Some companies are taking the unique approach of implementing treatment programs for failed applicants. Dr. Mitchell Rosenthal, founder of the non-profit substance abuse treatment organization Phoenix House and president of the Rosenthal Center for Addiction Studies, worked with Belden Inc. in Richmond Indiana to develop a program that committed to hiring people who tested positive for drug use. Applicants start as probational employees and are placed in treatment with local nonprofit and community groups, with the promise of a normal full-time job if they continue treatment and pass follow-up tests.

Employee assistance programs, or other partnerships and volunteer opportunities with philanthropic organizations, can help companies foster workplace environments in which employees feel comfortable seeking help, but this often depends upon the quality of the program. According to a report by the University of Massachusetts Lowell, such programs get mixed reviews from workers. For example, surveyed workers reported positive feedback when they felt the programs maintained a high level of confidentiality. Other respondents noted that some standard low-cost programs were not very helpful due to a lack of provided services.

The private sector also has the potential to “harness American brain power, entrepreneurship, and innovation…to present new ideas and invent solutions,” says Roger Krone, Chairman and CEO of information technology company Leidos, Inc. One example: Innovative healthcare technology companies are producing medical devices that can help treat pain and are developing monitoring programs that can assess patients who are at risk of addiction or overdose.

Challenges and Areas for Reform

Despite stereotypical ideas of what drug addiction looks like, the opioid epidemic affects Americans across the country at all levels of the socio-economic ladder. Catelin Morris explains more about the price of opioid addiction and stigma (10 min):

Gathering Data

Those at the highest risk of developing substance use disorders – including justice-involved populations, rural populations, veterans, and adolescents – need special attention and resources. Whether the billions of dollars of federal and state funding meets the needs of those at the highest risk is difficult to determine; annual overdose deaths are essentially the only measure of the effectiveness of interventions. Other evidence-based evaluations, such as non-fatal overdose data and data on use of naloxone, are necessary to understand whether grants are meeting the needs of at-risk populations.

The Overdose Detection Mapping Application Program (ODMAP), run by the University of Baltimore, for example, “provides near real-time suspected overdose surveillance data” to help link first responders to track overdoses, respond faster, and strategically analyze data across jurisdictions. See if any counties in your state participate here.

Curbing the Spread

Synthetic opioids and heroin have been the leading cause of opioid-related deaths in recent years. These drugs primarily come from international locations. China has been the primary source for trafficked fentanyl in the U.S., and even though China’s government banned the production and sale of fentanyl in 2019 (under international pressure), Chinese vendors continue to use online networks to ship directly to the U.S. as well as to drug cartels in Europe and Mexico. Mexico is also the primary source of heroin coming to the U.S., with a number of cartels controlling production and using major U.S. cities as distribution hubs.

An international dilemma often requires international cooperation. The Joint Criminal Opioid and Darknet Enforcement Team (J-CODE), under the DOJ, joined Europol in “a coordinated international effort to disrupt opioid trafficking on the Darknet,” essentially an international online black market. In September 2020, the operation reported it had confiscated over 500 kg of drugs worldwide, amounting to approximately $6.5 million worth of drugs.

Domestically, “pill mills” are what local and state investigators have termed doctors, clinics or pharmacies that prescribe or dispense narcotics inappropriately or for non-medical reasons. Even with the decrease in opioid prescriptions in recent years, Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs (PDMPs) are still highly effective. PDMPs “collect, monitor, and analyze electronically transmitted prescribing and dispensing data submitted by pharmacies and dispensing practitioners.” Each state manages its own PDMP, and uses the gathered data to support efforts in education, research, enforcement and abuse prevention.

Interventions

Medications

Naloxone (Narcan) is a short-acting drug which will bring a patient out of an opiate overdose by stripping the opiate from the opiate receptor. It is a life-saving drug. Naltrexone is a short-acting opiate/alcohol blocking agent, and Vivitrol is an extended-release form of Naltrexone. This blocks the opioid, causing withdrawal, yet provides no opioid to relieve pain during withdrawal.

Methadone is a gradually-acting opioid that reduces withdrawal symptoms that often drive users back to drug dependency. Buprenorphine is a synthetic opioid that produces weaker euphoric effects than heroin or methadone, which helps during withdrawal because it reduces or eliminates symptoms. There is also a relatively low risk of overdose.

These medications are proven to work, and when it comes to recovery from addiction, are especially effective through medication-assisted treatment (MAT). MAT uses medication in combination with counseling and behavioral therapies that can be tailored to meet individual patient needs. Many physicians also hope to reduce reliance upon opioids for treating pain in the first place. Alternative approaches to pain management are particularly important for patients with mood disorders. Chronic pain patients with mood disorders receive 51% of all opioid prescriptions and are at “increased risk of abusing opioids.” Cognitive behavioral therapy, acupuncture and acupressure, physical therapy, and massage are possibilities, but doctors often say it is easier to simply prescribe a pill because alternative treatments may be more expensive or receive less insurance coverage.

Community-based Efforts

Because 911 receives most emergency calls, law enforcement and emergency departments “have become the safety nets for behavioral health crises” due to a “lack of adequate and organized crisis services.” Jails are also in the mix; the prevalence of mental illness and substance use disorders in jails and prisons is three to four times greater than that of the general population.

Community-support models can address mental health, homelessness, and addiction without straining emergency departments and jails. The Police Assisted Addiction & Recovery Initiative (PAARI), a national network of almost 600 police departments across 34 states, provides resources to help law enforcement personnel develop non-arrest pathways for people with substance use disorders to receive treatment and recovery.

ODMAP is also fostering partnerships between law enforcement personnel and health departments, such as in Erie County, New York (3 min):

And in New Jersey (3 min):

For more on the role of police, see The Policy Circle’s Understanding Law Enforcement Brief.

SAMHSA’s National Guidelines for Behavioral Health Crisis Care also suggests ways to reduce the burden on law enforcement. A Regional Crisis Call Center as an alternative to 911 can “serve as an entry point to crisis services in many states and provide information and referral to callers on where to obtain assistance from local and national social services, government agencies, and non-profit organizations.” The FCC approved a new 3-digit behavioral health crisis number to replace the current National Suicide Prevention Lifeline’s number to make it easier to connect callers in crisis to resources. It is expected to take effect in mid-2022.

SAMHSA recommends Mobile Crisis Response Teams – small teams including a clinician and peer support professional – to be dispatched when individuals are experiencing behavioral health crises, and accompanied by emergency responders or police if necessary. To reduce the burden on emergency departments and jails, Crisis Receiving and Stabilization Facilities could assess and address mental health and substance use crisis problems. Supportive Housing programs also address the needs of homeless individuals with substance use disorders and acknowledge how homelessness and drug problems are intertwined.

Many communities already have programs that work at the local level. Anchor Recovery Community Center in Rhode Island deploys Peer Recovery Specialists to overdose hotspots. These peers engage with high-risk individuals without adding strain on law enforcement resources. In Manchester, New Hampshire, fire stations took the lead in serve individuals seeking help for substance use disorders. Through the Safe Station Program, fire department personnel conducted brief medical assessments and connected individuals to treatment and recovery resources until the opening of the Doorway of Greater Manchester, part of a state-wide network of recovery services.

Promoting physical activity can also be a way to replace addiction with something positive. A nonprofit group called The Phoenix provides access to a free gym for anyone who has been sober for at least 48 hours and a support network for people battling addiction. Since it was founded in 2006, The Phoenix has expanded to 36 states, with more than 77,000 members. CBS News took a deep dive into the Phoenix gym (6 min):

Funding

According to the Commonwealth Fund, Medicaid expansion is “associated with a wide range of positive insurance coverage, treatment access, and mortality outcomes for substance-use patients. With the federal government funding 90% of the cost, Medicaid expansion can be a key source of external funding for states to sustain opioid care providers and facilitate better access to patients.” Nationally, Medicaid expansion is associated with a 6% reduction in total deaths from opioid overdoses in states that have undergone expansion compared to non-expansion states. However, more data is necessary; some experts say that while Medicaid expansion has made addiction treatment more accessible, it has also made it less costly to obtain prescription opioids in the first place.

For more on the effects of Medicaid expansion, see The Policy Circle’s Affordable Care Act Brief.

In addition to Medicaid, emergency federal dollars are helping, but states say they need more sustainable and long-term funding in order to continue prevention and rescue efforts while still ensuring opioid addiction treatment is available. These costs are estimated to be at least $78 billion per year, which federal funding is not covering. In 2016, Congress authorized over $10 billion in federal funding for states, but only $2 billion was paid out between 2017 and 2019. In almost all states where legislatures have tried to place special taxes on opioid painkillers, drug company lobbying has prevented these measures from passing. Many state officials are instead counting on settlements in civil cases against drugmakers and distributors to bolster needed funds.

Lawsuits

Drugmakers, distributors, and pharmacies “have been sued by virtually every state and thousands of city and country governments.” Well over 2,000 lawsuits allege “the industry’s overly aggressive marketing of prescription painkillers and lax oversight over drug distribution contributed to widespread opioid addiction.” These suits coalesced in a district court in Ohio in 2018; over 10 companies were sued “in federal court in Cleveland by nearly 2,000 cities, towns and counties alleging that they conspired to flood the nation with opioids… The companies, in turn, have blamed the epidemic on overprescribing by doctors and pharmacies and on customers who abused the drugs.” Many of these companies have already paid over $1 billion in fines to the Justice Department and the FDA over opioid-related issues, and hundreds of millions to settle past state lawsuits.

Other settlements include:

- A $20 million settlement between Rochester Drug Cooperative (the sixth largest pharmaceutical distributor in the U.S.) and the federal government (April 2019);

- A $527 million settlement between Johnson & Johnson and Oklahoma (August 2019);

- A $260 million settlement between two Ohio counties and AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, McKesson, and Teva Pharmaceuticals. This settlement is on top of a previous $66.4 million settlement, but is not the end: “The settlement, if extrapolated to a nationwide deal resolving all litigation for the four defendants, suggests a settlement value of around $48 billion.” (October 2019);

- A $1.6 billion settlement between Mallinckrodt PLC (the country’s largest manufacturer of prescription opioid pills from 2006 to 2012) and 47 states and U.S. territories, plus lawyers representing thousands of local governments (February 2020);

- An $8.3 billion settlement between Purdue Pharma and the Justice Department, in which Purdue will also plead guilty to three felony counts of criminal wrongdoing (November 2020);

- Purdue Pharma was dissolved and the owning Sackler family are to pay $4.5 billion to settle opioid claims (September 2021)

- A $26 billion settlement between state attorneys general and three drug distributors (Amerisource Bergen, Cardinal Health, and McKesson) and Johnson & Johnson (February 2022).

In most cases, states and localities will receive the funds over the course of a set period of time, mostly through trusts meant to address the costs of opioid-addiction treatments that communities have been grappling with. See other settlements with the Opioid Settlement Tracker.

COVID-19

Although opioid-related fatalities were increasing before the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, national, state, and local reports suggest overdoses have increased. From social isolation and related anxiety to economic instability and challenges getting support, treatment providers and public-health officials have said the pandemic has only exacerbated the opioid epidemic.

As outlined in The Policy Circle’s Economic Growth Brief, people derive happiness and meaning through their work. The coronavirus pandemic has decimated the economy and job market, leaving millions of Americans unemployed or furloughed. Local economic conditions are generally strong predictors of drug-related deaths; a number of studies have found associations between increased state and local unemployment rates and drug overdoses, as well as links between county-level opioid overdose mortality rates and unemployment or factory closures. A strong economy provides stability and opportunity, and is an important component in the fight against the opioid epidemic and related problems of homelessness, hopelessness, and poverty.

Data from ODMAP indicated a 17.6% increase in suspected overdoses between mid-March and mid-May 2020, when states implemented stay-at-home orders, compared to overdoses before mid-March. More than 60% of participating counties reported an increase in suspected overdoses.

The pandemic prompted the federal government to relax rules around prescribing methadone and buprenorphine; doctors are no longer required to meet with patients in person before prescribing these medications, and can now dispense up to four week’s worth of medication rather than requiring daily visits. Take-home doses are associated with increased treatment engagement and hospitalization reductions.

Although this has helped, social isolation and lack of emotional support is still a problem for those in treatment. Opioid-related treatments are typically facilitated through in-person clinic visits; shutdowns and physical distancing have meant fewer patients go to facilities. This has also left addiction treatment specialists struggling; as patient volumes drop, costs at facilities have risen.

Additionally, pandemic-related transportation disruptions and border closings have interrupted supply chains of illegal drugs crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. Cutting the supply of drugs may seem like a positive turn of events, but it can also “heighten risks for users who seek new dealers and buy unfamiliar products” and make it “harder for people to judge the strength of the drugs they’re using.”

Conclusion

The federal government dedicates billions of dollars to addressing the nation’s opioid epidemic, but costs are far higher in terms of effects on the economy, the healthcare system, and individual American lives. A comprehensive national effort that coordinates local, state, and federal public policy with innovative solutions from the private sector and local communities has the potential to help individual Americans get the assistance they need and get back to safe, productive lives that will benefit all of American society.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Find out what your state and district are doing about the opioid epidemic and other drug crises.

- Do you know how prevalent drug overdoses or addiction are in your community or state?

- Has your governor declared a state of emergency?

- What are your state’s laws in relation to prescribing opioids?

- Is there a task force or does one need to be formed?

- Does your state or county have an agency participating in ODMAP?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Who are the members of drug- or opioid-related task forces in your state?

- Who is your state’s Prescription Drug Monitoring Program contact?

- What steps have your state’s/community’s elected/appointed official taken?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with law enforcement personnel, first responders, faith-based organizations, local hospitals, community organizations, school boards, or local businesses.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, communications@thepolicycircle.org, for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policy makers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Check your state’s department of health website for information on addiction, overdoses, legislation, and treatment programs.

- See what nonprofit and community organizations near you are targeting overdoses, and if there are volunteer opportunities.

- Contact your local businesses, or even your local Chamber of Commerce, to see how opioid addiction is affecting the workplace in your community.

- Learn what schools in your district are doing to teach students about substance use disorders.

- Are there mentorship opportunities for at-risk youth in your community?

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.

Thought Leaders and Additional Resources

- Dreamland by Sam Quinones

- 5 books to help you understand the opioid crisis.

- TedTalk: Everything you think you know about addiction is wrong

- Politico: The Opioid Crisis: What Caused it and How Bad is It?

- AEI’s Faces of Policy Docuseries: The Opioid Crisis

- Quit Heroin – resources: homeless, addicted, incarcerated

- American Association for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence

- Center of Excellence for Integrated Health Solutions (Funded by SAMHSA)

- Overdose Detection Mapping Application Program

- WaPo: DEA Pain Pill Database

- National Safety Council: National Plan to Address Opioid Misuse

- NCSL: Database – see legislation that focuses on prescription drug monitoring programs, prescribing guidelines and limits, pain clinics and management, etc.

- Bipartisan Policy Center: Tracking Federal Funding to Combat the Opioid Crisis

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.