Terror groups and rogue states all represent distinct threats to U.S. national security and the safety of our allies. Read on for a deep dive into prominent terror groups and rogue states, their impacts locally and globally, and responses from the U.S.

Introduction

Read The Policy Circle’s Executive Summary here. To review The Policy Circle’s Brief on Foreign Policy in the Middle East click here.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) defines International Terrorism as “violent, criminal acts committed by individuals and/or groups who are inspired by, or associated with, designated foreign terrorist organizations or nations (state-sponsored).”

A rogue state is a term used to “designate regimes that employed terrorism as an instrument of state policy and attempted to acquire weapons of mass destruction in pursuit of policy goals.”

The U.S. Secretary of State designates Foreign Terrorist Organizations through the State Department’s Bureau of Counterterrorism’s (CT) continual monitoring. When examining possible organizations, CT “looks not only at the actual terrorist attacks that a group has carried out, but also at whether the group has engaged in planning and preparations for possible future acts of terrorism or retains the capability and intent to carry out such acts.”

Once a group is identified, the Bureau prepares a record of information that proves the requirements are met to be designated as a Foreign Terrorist Organization. If the Secretary of State, the Attorney General, and the Secretary of the Treasury decide to make the designation, Congress is notified and given seven days to review. Unless Congress opposes the designation, it takes effect. Organizations designated are allowed to seek judicial review within 30 days of the designation.

The Secretary of State can delist Foreign Terrorist Organizations if the circumstances for the original designation have improved or the national security of the U.S. requires the designation to be revoked.

Criteria for Designation

- The organization must be a foreign organization;

- The organization must engage in terrorist activity, according to definitions set by the Immigration and Nationality Act, or retain the capability and intent to do so;

- The organization’s terrorist activities must threaten the security of U.S. nationals or U.S. national security.

Legal Ramifications

- No U.S. persons can knowingly provide material, informative, or financial support or resources to designated groups;

- Representatives and members of designated groups, if they are aliens, are not allowed entry to the U.S. and, in some instances, are removable from the U.S.;

- Financial institutions that become aware of their possession of or control over funds tied to a designated group must report those funds to the U.S. Department of Treasury.

Other impacts of designation include efforts to curb terrorism financing and international encouragement to do so, and national and international awareness, stigma, and isolation.

See a full list of U.S.-designated foreign terrorist organizations here. This Policy Circle Deep Dive focuses on the following foreign terrorist organizations:

Hamas

Overview

Hamas is a militant movement that also serves as one of the Palestinian territories’ two major political parties. This entity is a Palestinian Sunni Islamist group. In 2006, it won a majority of seats in the legislature and formed a government. It governs more than 2 million Palestinians in the Gaza Strip and “is best known for its armed resistance to Israel.” The United States, the European Union, and many other countries have designated Hamas as a terrorist organization, although it should be noted that “some apply this label to only its military wing.”

Hamas is an acronym for Harakat al-Muqawama al-Islamiya, which translates to “Islamic Resistance Movement.” Hamas was founded by Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, who was a Palestinian cleric and went on to become an activist in local branches of Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood. In 1987, Yassin established Hamas as the political arm of the Brotherhood in Gaza following the first intifada, “a Palestinian uprising against Israeli occupation of the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem.”

2023 Conflict

“Not since the Holocaust has this large a number of Jews been killed in a single day.”

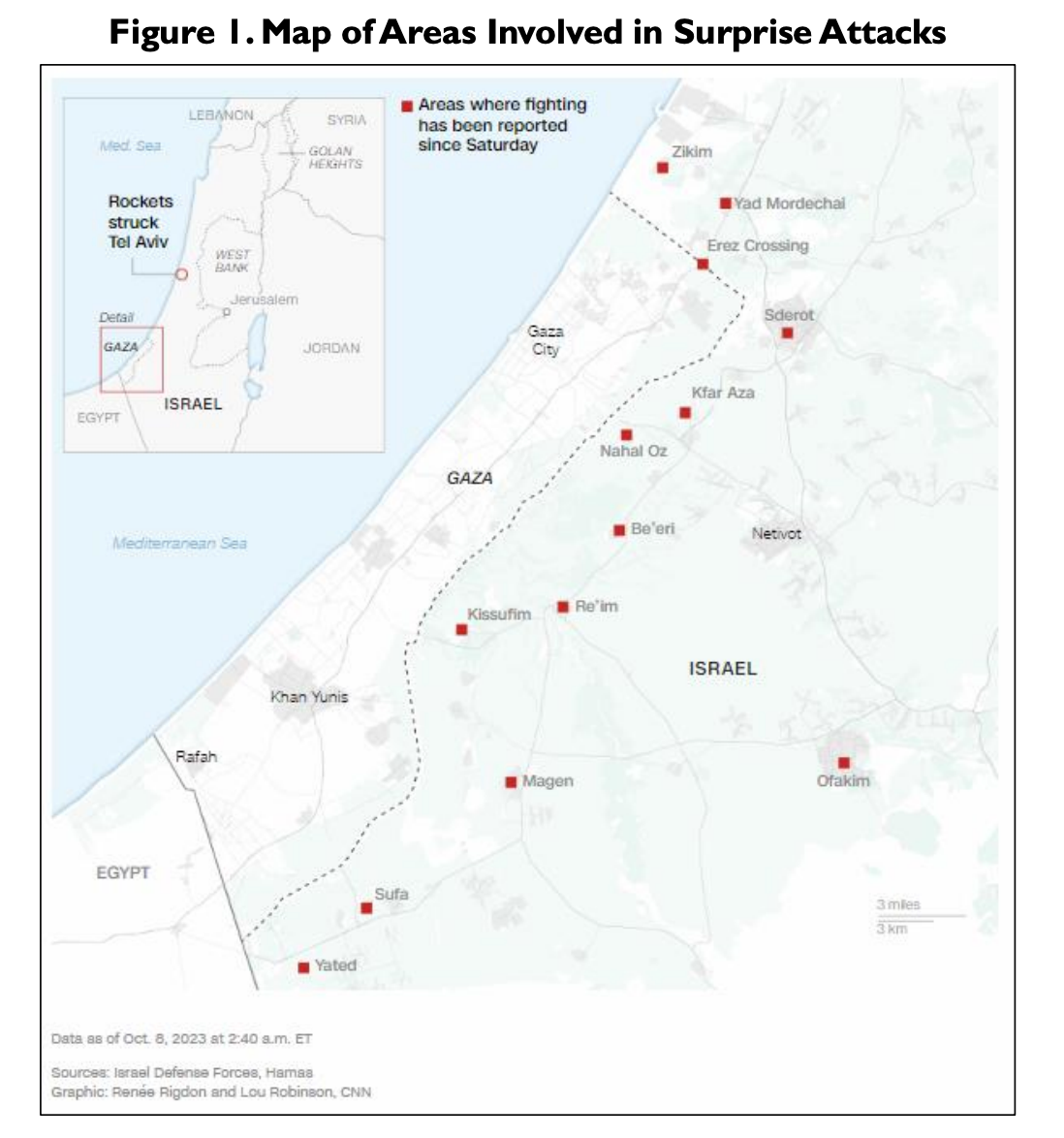

In October 2023, Hamas launched a series of surprise attacks by land, air, and sea against Israel. The attacks were launched during the Jewish high holiday of Simchat Torah. This attack comes after nearly 50 years following a previous attack in 1973 that sparked the Yom Kippur War.

See Figure 1. below for a map of areas involved in the attacks

The multipronged assault on Southern Israel has killed nearly a thousand Israelis, including civilians and children, and already has “killed more people than all Hamas attacks since 2007 combined.” Hamas has also taken an estimated 150 Israeli hostages, many of them civilians. The White House confirmed that at least 32 Americans were killed in the ongoing violence (as of 10/27/23), and many more are unaccounted for and have possibly been taken hostage.

While speculation surrounding Iran’s role continues to grow, the Biden Administration and Israel have shared publicly that there has been no confirmed evidence that the Iranian government played a direct planning role. However, the Shia Islamist group Hezbollah (a U.S. designated Foreign Terrorist Organization) made claims that Hamas did receive support for the attacks from Iran. Further, a number of “Iranian officials have praised the assault publicly.” Qatar also plays a unique role in the conflict. Qatari mediators and Qatar’s foreign ministry have confirmed its involvement in mediation talks with Hamas and Israeli officials, including over a possible prisoner swap. Hezbollah has exchanged fire “in solidarity” with Hamas, and escalation with Hezbollah and Israel is possible.

Israel’s response has been a massive push for swift action, with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu declaring war and launching Operation Iron Swords. The Israeli government announced a “total siege” on Gaza and has conducted a massive wave of airstrikes in Gaza, with an estimated 680 Palestinians killed. It should be noted that “Hamas has reportedly threatened to kill hostages in the event of Israeli strikes on civilian targets in Gaza.”

Read on to learn more of the background of Hamas and the U.S. response and strategy.

Supporters of Hamas

Hamas is cut off from any aid from the United States and European Union due to its designation as a terrorist entity. Qatar is a strong financial supporter and foreign ally of Hamas. Qatar has reportedly transferred $1.8 billion to support Hamas.

Under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Turkey has been increasingly supportive of Hamas, and before the violence in October 2023, expressed support for Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh. Though Turkish Officials share that their support only extends politically, it has in previous years been accused of financially funding terrorist efforts of Hamas.

Historically, Hamas had opportunities to increase revenue through a series of tunnel networks built into Egypt and moving goods through the tunnels. Egypt most recently shifted in 2013, when President Adel Fatah al-Sisi took office, and Egypt became more hostile towards Hamas. While the Egyptian army shut down a majority of the underground tunnels within its borders, the Egyptian government did allow some commercial goods to enter Gaza through its border in 2018.

Today, Iran is one of the largest supporters of Hamas and reportedly provides around $100 million annually to Hamas and other Palestinian groups that the United States designates as terrorist organizations.

Areas of Operation

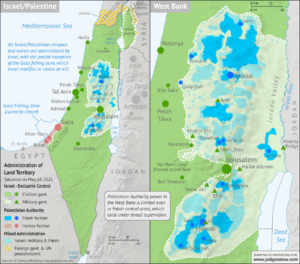

Hamas formed a unity government with rival party, Fatah in 2006, but the two continued to clash, and Hamas expelled Fatah from the Gaza Strip in 2007. Additionally, “Hamas is organizationally split across four sectors: the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, the Palestinian diaspora, and Israeli prisons.”

Key Beliefs/Ideology

Hamas’s original 1988 charter called for “the destruction of Israel and the establishment of an Islamic society in historic Palestine” in Israel’s place. The group views all of the land of Mandate Palestine (with the exception of the land that became modern-day Jordan) “as an Islamic birthright that has been usurped.” Hamas refuses to recognize the state of Israel and rejects peace talks and a two-state solution. In 2017, Hamas attempted to soften its image with a new document calling for “an interim Palestinian State,” but still refuses to recognize Israel and reaffirms its dedication to “armed resistance.”

Hamas is “firmly in control of Gaza’s government institutions and security services.” The political bureau is Hamas’s principal authority, but the Shura Council serves as Hamas’s central consultative body and is responsible for making decisions. Smaller committees under the Shura council supervise government activity, including military operations and media relations. Additionally, regional political bureaus oversee the affairs of Palestinians in the West Bank, the Palestinian diaspora, and Israeli prisons.

Since it is designated a terrorist organization, Hamas does not receive official international assistance. Islamic charities have channeled money to Hamas-backed social service groups, but the U.S. Treasury has frozen many of these assets. Private donors in the Gulf provide a significant amount of funding, and Iran contributes funds, weapons, and training. Turkey insists it “only backs Hamas politically” but has been accused of funding Hamas. Cryptocurrencies have also been an option to “bypass international financial sanctions.”

Egypt and Israel have largely kept their borders with Gaza closed since 2006. The blockade essentially forces a reliance on international aid for Gazan Palestinians, mainly through UN agencies. Egypt began to allow some commercial goods to enter Gaza in 2018, and Hamas reportedly collects $12 million per month from taxes on these imported goods.

Violence between Israel and Gaza has been constant over the past few decades. Hamas has a history of using suicide bombings as a tactic against Israeli citizens since the 1990s and has also launched rockets into Israel. Militants frequently fly weaponized balloons toward Israel, which spark fires. In 2014, Israel accused Hamas of kidnapping and murdering three Israeli teens in the West Bank; there were indications that a rogue cell abducted the teens, highlighting “Hamas’s inability to control all those affiliated with it, analysts say.” In May 2021, Hamas and Israel “entered their deadliest conflict in six years” when riots broke out among Palestinians in Jerusalem and Israeli police. It should be noted that this was the deadliest up until the recent October attacks. Hamas launched rockets from the Gaza Strip into Israel, claiming it was in retaliation for Israeli aggression towards Palestinians during the riots. Israel and Hamas continued to fire rockets at each other for ten days before the U.S. and Egypt brokered a ceasefire.

Interaction With the Local Population

Hamas won a majority of seats in the legislature and established a government in 2006, earning votes for the social services it provided. It also established a judiciary and governed “in accordance with the Sharia-based Palestinian Basic Law,” although it is much more restrictive and reportedly represses the media, activism on social media, political opposition, and NGOs. In 2020, Freedom House reported the “Hamas-controlled government has no effective or independent mechanisms for ensuring transparency in its funding, procurements, or operations.”

However, after the May 2021 conflict, Hamas won more support “as the champion of the broader Palestinian national movement for the first time in years by attacking Israel in response to tensions in Jerusalem.” It also continues to provide social services to Palestinians. At the same time, conflict has made life infinitely more difficult for those living in Gaza; the United Nations has assessed that the conflicts between Israel and Hamas in 2008-2009, 2012, 2014, and 2021 have cumulatively killed over 4,000 people in Gaza, destroyed over 245,000 homes in Gaza, and cost $5.7 billion in damages in Gaza.

A June 2021 survey found “positive perception among Gazans of their living conditions stood at 14%,” and 40% indicated they would consider leaving Gaza permanently. According to Palestinian authorities, 70% of the 2 million residents in Gaza are under the age of 30, and unemployment amongst these young adults stands at 62% as of summer 2021. There are no updates yet for local surveys following the October 2023 attacks, but humanitarian groups and civilians are working to protect those stuck in the blockade of Gaza and ongoing fighting.

U.S. Strategy

The U.S. designates Hamas as a terrorist organization and refuses to recognize the legitimacy of the Hamas government. The U.S. also works with the international community in relation to Hamas. The Middle East Quartet – the United States, the UN, the EU, and Russia – “asserts that any Palestinian government involving Hamas can only receive international recognition and aid if the group recognizes Israel, renounces violence, and accepts the [Palestinian Liberation Organization’s] signed agreements with Israel.

Following the attacks in October of 2023, President Biden shared that “all appropriate means of support to the Government and people of Israel” will be offered. The U.S. Congress has already appropriated $3.3 billion a year for Israel in Foreign Military Financing through FY 2028. The spokesman for the National Security Council, John Kirby, also shared that the first batch of immediate “military aid in the wake of the violent assault by Hamas militants is making its way to Israel.” U.S. officials are on high alert and watching Hezbollah closely alongside extremists and militant groups in the region. With the ongoing support for Ukraine and the additional support to Israel, alongside the need to maintain security for America, some have raised concerns about the supply of munitions. Army Secretary Christine Wormuth shared the need for swift Congressional action to pass funding for support as needed. U.S. officials may also consider a provision of humanitarian assistance to Palestinian civilians.

See these overviews from the Council on Foreign Relations and the Counter Extremism Project for more information.

Hezbollah

Overview

Hezbollah is a Shiite Muslim political party and militant group that resists Israeli and Western involvement in the Middle East. Hezbollah, translating to “Party of God,” is an Iran-backed militant group. It established itself in 1982 during the Israeli Occupation of Southern Lebanon. It maintains an extensive security apparatus, political organization, and social services network in Lebanon, where the group is often described as a “state within the state.” However, as it has become increasingly embroiled in the Syrian civil war supporting the Assad regime, it has alienated some of its Lebanese constituents, predominantly Sunni Muslim Syrian rebels. The U.S. government and other countries have designated Hezbollah as a terrorist group. Following the developments of the October 2023 Hamas attacks on Israel, reports have emerged of Hezbollah’s involvement in the planning of the attack and direct involvement following firing across the Israeli border. Hezbollah described the deadly recent attack as a “decisive response to Israel’s continued occupation.”

Areas of Operation

Hezbollah controls most of Lebanon’s Shiite-majority areas, which include parts of Beirut, southern Lebanon, and the eastern Bekaa Valley region. The group has also been accused of committing acts of terrorism against Israeli and Jewish targets abroad, and there is evidence of Hezbollah operations in Africa, the Americas, and Asia. Hezbollah also has “its own camps to train members as well as members of other terrorist organizations.”

Key Beliefs/Ideology

Hezbollah’s 1985 manifesto outlined the goals of seeking “to destroy Israel, to expel Western influences from Lebanon and the wider Middle East, and to combat its enemies within Lebanon… The group considered the international system and the 1985 Lebanese government subject to imperial influences and hostile to Islam, and it denied Israel’s right to exist…”

A new manifesto in 2009 signaled a shift when Hezbollah transformed into a hybrid state actor and “began to consider the established Lebanese political system an appropriate channel through which to gain influence.” It no longer calls for “Islamic governance as the only option for Lebanon’s future.” However, it continues to highlight its goal of liberating Palestine, its opposition to the United States, and its commitment to fight Israeli expansion and aggression.

Structure & Activities

The Shura Council is the main organizational body of Hezbollah, with five sub-councils: the political assembly, the jihad assembly, the parliamentary assembly, the executive assembly, and the judicial assembly. All together, Hezbollah has strong military, political, and social branches and has been a part of the Lebanese government since 1992, when eight members were elected to Parliament. The party has held cabinet positions since 2005.

Animosity continues between Israel and Hezbollah, even after Israel officially withdrew from southern Lebanon in 2000. Constant conflict “escalated into a month-long war in 2006, during which Hezbollah launched thousands of rockets into Israeli territory.” There has been no relapse into war, but Western officials suspect Hezbollah has attacked Israel with sophisticated technology supplied by Iran. Hezbollah’s military arm is estimated to have up to ten thousand active fighters, and the Center for Strategic and International Studies reported in 2018 that it was “the world’s most heavily armed non-state actor.”

Hezbollah’s activity in Syria also poses concerns for U.S. interests in the region. In 2011, Hezbollah sent military advisors to aid the al-Assad regime in Syria’s civil war; in 2013, Hezbollah confirmed it deployed combat forces to aid Assad’s troops. Extending influence into Syrian territory also “provided routes for transporting Iranian missile parts and weapons.”

Hezbollah reportedly “receives hundreds of millions of dollars from legal businesses, international criminal enterprises, and the Lebanese diaspora.” Even so, Iran is Hezbollah’s primary patron, and American sanctions on Iran have affected Hezbollah’s financing. Hezbollah has had to shut offices in Lebanon and cut the pay of its employees and militants. Further, as of a 2023 Congressional Research Services Report, the expansive network of collaborators that Hezbollah built has continued to expand its efforts to fund the trafficking of drugs and firearms throughout the EU and beyond.

Interaction With the Local Population

Hezbollah is often called a “state within a state” because, in addition to its terrorist activities, it is also a political group providing social services to the Lebanese population. Social services Hezbollah provides include “infrastructure, health-care facilities, schools, and youth programs,” which have garnered support for Hezbollah among both Shiite and non-Shiite Lebanese.

At the same time, some analysts believe Hezbollah faces backlash that focusing on the war in Syria led it to neglect domestic interests. Sunni Muslims have also been less supportive, as the Assad regime particularly threatens Sunni Muslims.

Protest movements may be a threat; in January 2020, the “formation of a Hezbollah-backed government under Prime Minister Hassan Diab failed to appease anti-establishment protesters,” and unemployment, poverty, and debt have persisted.

On August 4, 2020, an explosion at Beirut’s port that killed at least 200 people brought on protests against government corruption. In response, Prime Minister Diab dissolved the government on August 10. After 13 months of political stalemate, a new government was formed in September 2021, although the economic collapse – shortages of food, fuel, and medicine, with 75% of the population living in poverty – has not improved. The World Bank described the economic collapse as one of “the three worst crises anywhere in the world since the mid-1800s” and blamed political stalemate. Hezbollah denied it intentionally delayed the process by not cooperating with the proposed government.

U.S. Strategy

U.S. strategy has often relied on targeting Hezbollah’s revenue streams. In 2015, Congress passed the Hizballah International Financing Prevention Act, “which sanctions foreign institutions that use U.S. bank accounts to finance Hezbollah. Saudi Arabia and the U.S. also co-lead the Terrorist Financing Targeting Center, meant to “disrupt resource flows to Iran-backed groups such as Hezbollah.”

The U.S. is also in talks with Egypt and Jordan “to help find solutions to Lebanon’s fuel and energy needs,” as Lebanon faces a “financial crisis which the Lebanese state and its ruling factions, including Hezbollah, have failed to tackle even as fuel has run dry and shortages have triggered deadly violence.”

President Biden’s administration has, within the last few years, sanctioned individuals connected to the financing arm of Hezbollah. With Lebanon in a very precarious political situation and geographical location in the region, Hezbollah has seized the opportunity to continue to expand in spite of sanctions and other measures.

Following the October 2023 attacks, the U.S. government and senior level officials warned Hezbollah and other groups in the region, with senior U.S. defense officials sharing that they are “deeply concerned about Hezbollah making the wrong decision and choosing to open a second front to this conflict.”

See these overviews from the Council on Foreign Relations, the Counter Extremism Project, and Stanford’s Center for International Security and Cooperation for more information.

Islamic Republic of Iran

Overview

Known as Persia until 1935, Iran became an Islamic republic in 1979 after the monarchy was overthrown and “[c]onservative clerical forces led by Ayatollah Khomeini established a theocratic system of government.” Relations with the U.S. became strained in November 1979 when a group of Iranian students seized the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and held embassy personnel hostage until mid-January 1981. The U.S. cut off diplomatic relations with Iran in April 1980. From 1980-88, Iran fought a war with Iraq that eventually expanded into the Persian Gulf and involved clashes between U.S. Navy and Iranian military forces. Iran has been designated a state sponsor of terrorism and remains subject to U.S., UN, and EU economic sanctions due to its “continued involvement in terrorism and concerns over possible military dimensions of its nuclear program.”

Key Beliefs/Ideology

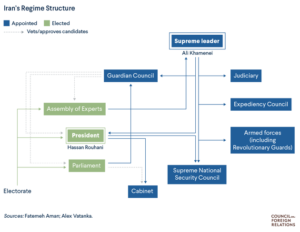

The aim of the Iranian Revolution “was to upend the reign of the shah and restore Islamic ideology to Iranian society. Under Khomeini, “the Iranian religious and political landscapes were dramatically transformed, making Shia Islam an inseparable element of the country’s political structure.” Following the 1979 revolution, changes to the constitution established a system of government with three branches – executive, judicial, and legislative – and Khomeini sitting at the top, arguing “that governments should be run by those with higher rank among clergies.” The Iranian system “is dominated by a small cadre of religious clerics and revolutionary forefathers,” which leaves church and state heavily intertwined.

Iran’s leadership is comprised of both elected and appointed institutions:

- The Supreme Leader (Ayatollah Khamenei, Khomeini’s successor): The most powerful individual in the Iranian regime

- Assembly of Experts: An 86-member group of clerics that elects the supreme leader

- President (Ebrahim Raisi): The top of the executive branch officially, but answers to the Supreme Leader

- Majlis: Parliament, made up of 290 members who represent Iran’s 30 provinces. Passes legislation.

- Council of Guardians: Reviews legislation for consistency with Sharia law, made up of 12 members, 6 appointed by the Supreme Leader and 6 approved by the Majlis.

- Expediency Council: Resolves disputes between the Majlis and the Council of Guardians.

- Supreme Court: Highest judicial body – sets judicial precedent.

- Special Clerical Court: Tries clergy members for crimes, especially ideological ones. Overseen by the Supreme Leader

The Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) is another entity that wields considerable power in Iran. As the Counter-Extremism Project explains, “the IRGC is Iran’s primary instrument for exporting the ideology of the Islamic Revolution worldwide. It is…Iran’s main link to its terrorist proxies, which the regime uses to boost Iran’s global influence.” The IRGC operates separately from the regular military and is believed to have influence over at least half of the Iranian economy.

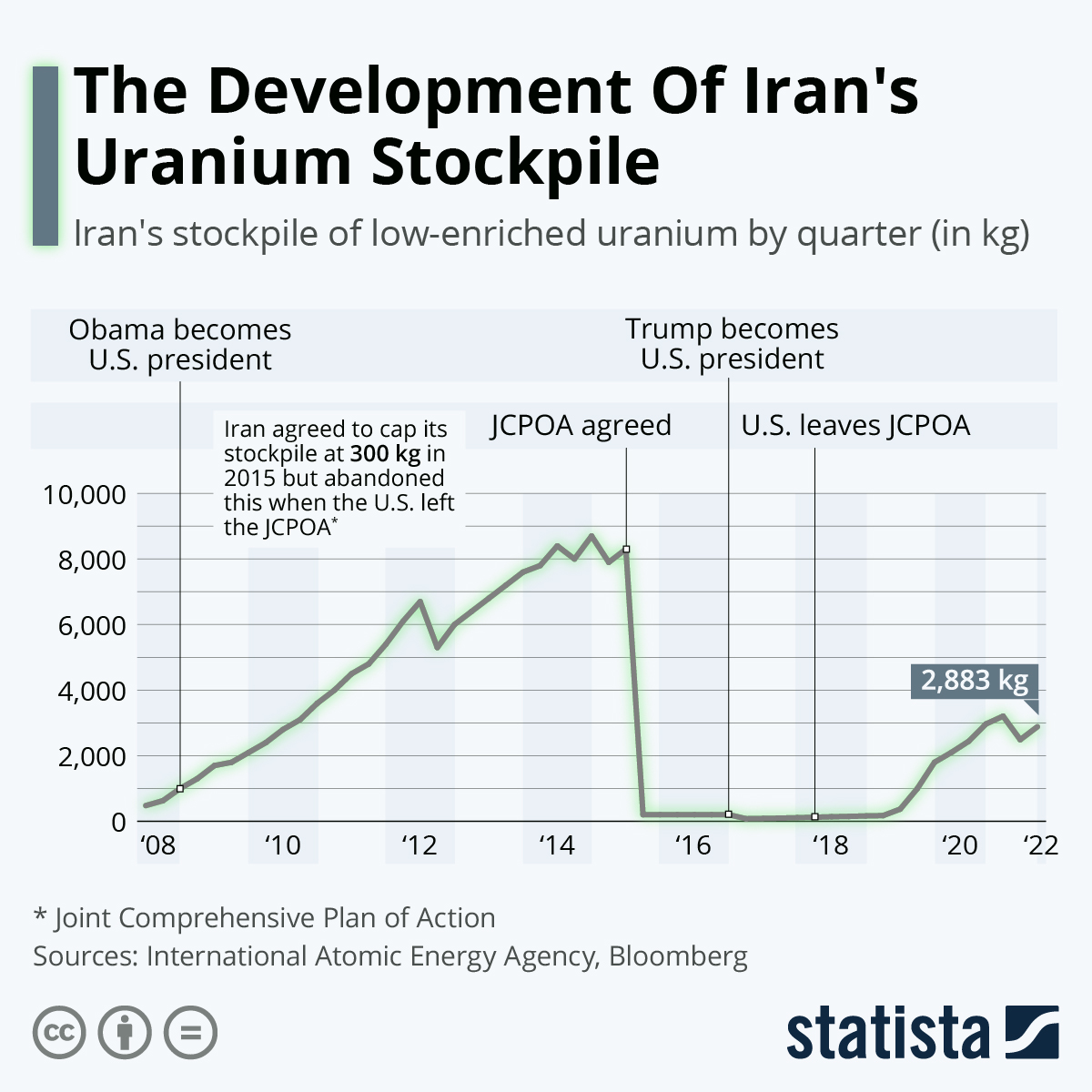

Iran’s quest for nuclear weapons, “ballistic missile program, and support for terrorism” are also areas of increasing concern. The international community endeavored to address this with the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), an agreement involving the UK, China, France, Germany, and Russia that would limit Iran’s nuclear capabilities in return for eased economic sanctions. When the U.S. withdrew from the JCPOA, Iran began to violate the terms of the deal, claiming the violations were in response to the U.S. withdrawal.

Inspectors from the United Nations reported in early 2023 that Iran had “enriched trace amounts of uranium to nearly weapons-grade levels, sparking international alarm.”

The Biden administration attempted in 2022 and the early months of 2023 to revive the nuclear deal. However, due to Iran’s recent deal with Saudi Arabia, brokered by China, and Iran estimated to be between four to nine months away from reaching the nuclear threshold, the nuclear deal is off the table.

Iran supports the Assad regime in Syria; has reportedly provided support to Houthi insurgents fighting against the U.S.-supported Saudi-led coalition in Yemen; supports Hezbollah in Lebanon, and supports Shia militia groups against U.S.-backed Sunni and Kurdish groups in Iraq.

In September 2023, five Americans were released from wrongful imprisonment in Iran for years and returned to American soil. The group of Americans were freed in conjunction with a prisoner exchange agreement negotiated by the Biden Administration and Iranian officials. Through the prisoner exchange agreement, Tehran was able to access $6 billion in “oil revenues frozen under U.S. sanctions and also saw five Iranian nationals released from U.S. custody.”

Interaction With the Local Population

The Iranian regime is extremely repressive. Amnesty International deemed 2018 the “year of shame” after Iranian authorities arrested over “7,000 protesters, students, journalists, environmental activists, workers and human rights defenders, many arbitrarily.” The State Department’s 2020 Human Rights Report on Iran found human rights abuses included “numerous reports of unlawful or arbitrary killings,” “forced disappearance and torture by government agents, as well as systematic use of arbitrary detention and imprisonment,” “serious problems with independence of the judiciary,” “unlawful interference with privacy,” “severe restrictions on free expression, the press, and the internet,” widespread corruption at all levels of government,” “lack of meaningful investigation of and accountability for violence against women,” “violence against ethnic minorities,“ and “crimes involving violence and threats of violence targeting [LGBTQ] persons…”

Triggered by the death of Masha Amini in September 2022, “while in the custody of the Guidance Patrol (also known as the ‘morality police’) for allegedly violating the hijab dress code,” civilians erupted in protest against the Islamic Republic. While nationwide demonstrations quieted in 2023, the ACLED reported that between mid- September and December 2022, Iran experienced the highest number of violent protests since 2016.

U.S. Strategy

The U.S. has not had diplomatic relations with Iran since the U.S. embassy in Tehran was seized in 1979, after which Iran “ground[ed] its identity and legitimacy in anti-Americanism.” In 2013, former Iranian President Rouhani and former President Obama held the first phone conversation between the two countries since 1979. They began discussions for the eventual JCPOA. The JCPOA was criticized for many reasons, and former President Trump officially withdrew U.S. participation in May 2018, “citing a lack of progress limiting Iran’s nuclear weapons development program and a failure to adequately deal with Iran’s missile program.”

The Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” strategy reimposed sanctions to compel Iran to renegotiate a new version of the JCPOA. Since mid-2019, Iran has responded to increasing sanctions by decreasing its nuclear commitments to the JCPOA. Some experts note sanctions “have arguably not, to date, altered Iran’s pursuit of core strategic objectives,” although they have restricted Iran’s government and brought on Iran’s worst economic crisis in 40 years.

Since May 2019, U.S.-Iran tensions have been high: the Trump administration blacklisted the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) as “a foreign terrorist organization” in April 2019. Other conflicts included attacks on oil tankers and a U.S. surveillance drone being shot down. Additionally, “Iran and Iran-linked forces have attacked and seized commercial ships, caused destruction of some critical infrastructure in the Arab states of the Persian Gulf, and posed threats to U.S. forces and interests.” Tensions have continued since early 2020, when an American contractor was killed at an Iraqi military base and a drone strike killed Iran’s top general Qassem Soleimani.

Since, the U.S. confiscated Iranian oil on the way to Venezuela, claiming this was in violation of U.S. sanctions (August 2020); Iran blamed Israel, a key U.S. ally, for killing a top nuclear scientist (November 2020); the U.S. carried out air strikes against Iran-backed targets in Syria, in response to threats against the U.S.-led coalition in Iraq (February 2021); the U.S. blamed Iran for an attack on an Israeli-linked tanker (August 2021); the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps have claimed responsibility for a missile attack near a U.S. military base in Iraq (March 2022).

Regarding the impossibility of resurrecting the Iran Nuclear Deal, the Biden administration has pivoted its strategy dealing with a soon-to-be nuclear powerful Islamic Republic of Iran. The United States currently “seeks to prevent an Iranian bomb, avoid the risky escalation that could come with heightened pressure, and kick the can on a diplomatic solution in the hopes that conditions for a new deal to replace the JCPOA become more favorable over time.”

Following the October 2023 Hamas attacks on Israel, and the potential involvement and support from Iran, the Biden Administration has shared that it is “reserving the option to halt Iran’s access to $6 billion it is set to receive as part of a prisoner exchange deal.”

The Taliban

Overview

The Taliban emerged in 1994 in the power vacuum left after the Soviet Union withdrew from Afghanistan. “Disappointed that Islamic law had not been put in place following the ousting of communist rule,” leader Mullah Omar gathered a group of students and promised stability after years of conflict among mujahideen groups. Taliban means “students” in Pashto, and Pashtuns are the majority ethnic group in Afghanistan, particularly in the south and east and in Pakistan’s north and west.

The Taliban gained widespread support and came to power in Afghanistan in 1996 and ruled according to a strict interpretation of sharia law that “required women to wear the head-to-toe burqa, or chadri; banned music and television; and jailed men whose beards it deemed too short.” In 2001, U.S. and NATO forces removed the Taliban from power. The Taliban regrouped in Pakistan and spent two decades leading “an insurgency against the U.S.-backed government in Kabul,” which in August 2021 resulted in the Taliban regaining control of Afghanistan. To read more on the collapse of Afghanistan in 2021, visit the Council on Foreign Relations’ report here.

Areas of Operation

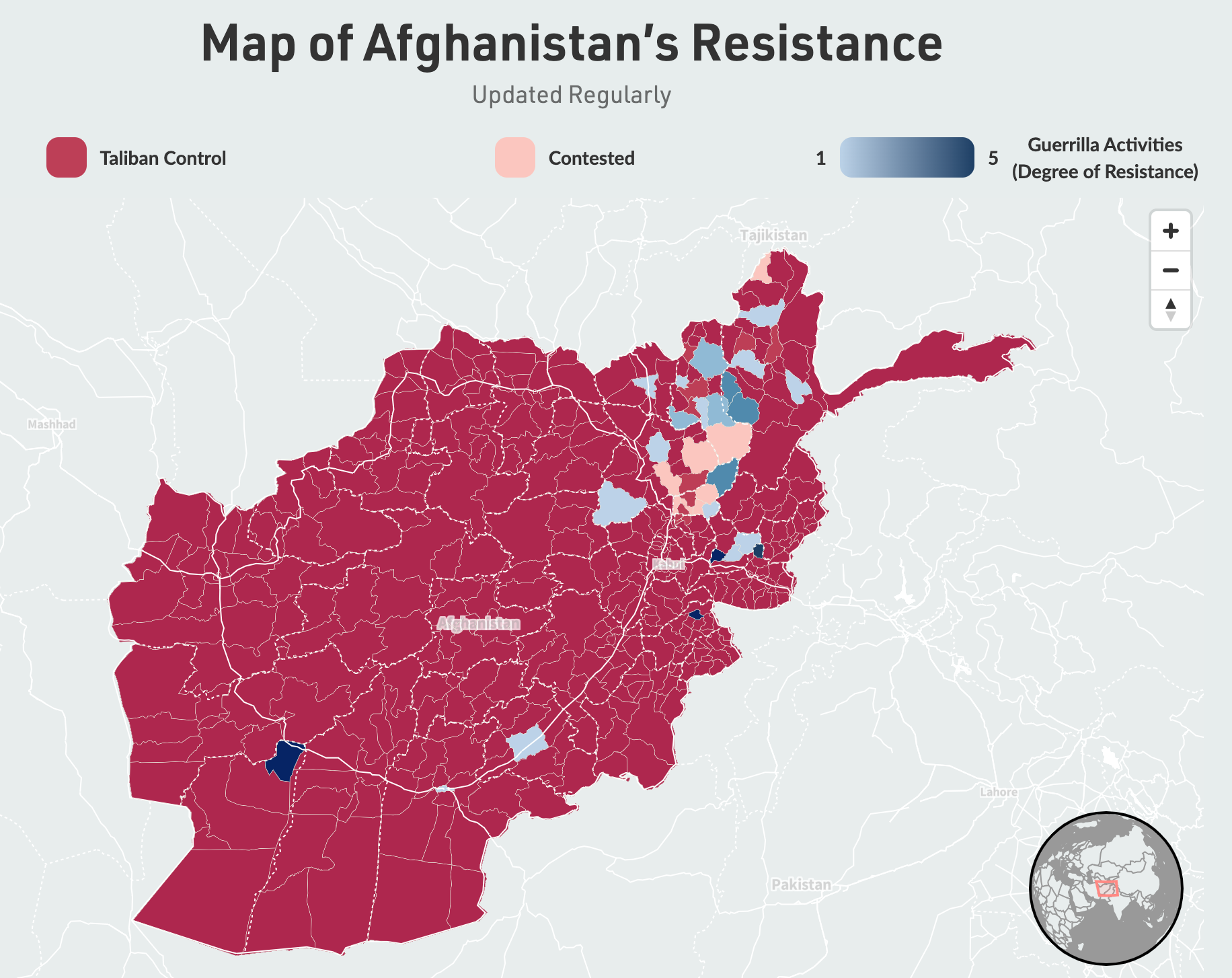

The Taliban operated in Afghanistan until 2001 when the U.S. invaded and helped overthrow the Taliban for harboring al-Qaeda. After 2001, it primarily operated from hideouts in Pakistan and in some border areas of Afghanistan. By 2005, the Taliban had recovered enough influence and power to begin an insurgency that directly challenged the United States and international military forces. After the United States led a “surge” against the Taliban between 2009 and 2011, the number of U.S. forces decreased in Afghanistan, and Afghan forces worked to take control of the nation’s security.

The Taliban gained more ground in Afghanistan; in 2018, the Taliban was in full control of 14 districts, or about 4% of the country, and active in another 263 districts, or 66% of the country. Over the summer of 2021, as U.S. and NATO troops withdrew, the Taliban quickly advanced and took full control of Afghanistan.

While the Taliban quickly defeated the last remains of resistance within a month of taking the capital city of Kabul on August 15, 2021, the National Resistance Front gained momentum by the Spring of 2022. Despite sending forces into districts known for resisting the Taliban’s rule, the Taliban has been unsuccessful in eliminating Afghanistan resistance in 2023.

Key Beliefs/Ideology

According to Stanford University’s Mapping Militant Organizations project, “the Taliban’s main goal is to establish a Taliban-controlled government in Afghanistan.” The ideology is seen as a shift away from traditional Islam towards a more “strict interpretation and enforcement of Sharia law.” Osama bin Laden’s jihadist and pan-Islamist views are also represented in Taliban governance.

Taliban rhetoric often includes “religious and historical references” and asserts “that the Taliban are engaged in a righteous jihad aimed at establishing a divinely ordered Islamic system in Afghanistan.” Despite “a narrow social base” with much of the power concentrated in the hands of leaders, the Taliban “focuses on internal affairs,” “maintaining cohesiveness,” and “enforcing their doctrine of obedience,” according to the United States Institute of Peace.

Structure & Activities

After 2001, most experts believed the Taliban’s leadership was based outside the country, primarily in Pakistan. The leadership council, known as the Quetta Shura, makes decisions for all political and military affairs. Mawlawi Haibatullah Akhundzada is the current leader of the council since the deaths of the original leader, Mullah Omar, in 2013 and his successor, Mullah Akhtar Mohammad Mansour, who was killed in a 2016 U.S. airstrike in Pakistan.

The Taliban collaborates closely with the Pakistan-based terrorist Haqqani network. This militant Sunni Islamist organization was allied with the Afghan Taliban during the 1990s and is considered “the most lethal and sophisticated insurgent group targeting U.S., Coalition, and Afghan forces in Afghanistan.” The Taliban does not, however, have the same relationship with ISIS; the Taliban views ISIS “as a threat to its goal of establishing a unified Islamist movement with the goal of expelling Western powers due to its extremism.”

Al-Qaeda remains close with the Taliban, heightening concerns that the Taliban is providing a haven for terrorists. The UN reported in April of 2022 “that al-Qaeda is likely using Afghanistan as a “friendly environment” to recruit, train, and fundraise.”

The Taliban earns revenue through criminal activities, including “opium poppy cultivation, drug trafficking, extortion of local businesses, and kidnapping,” the UN monitoring group reports. Additionally, the Taliban levies taxes on commercial activities in the territories it controls and collects customs revenue at border crossings. Annual income estimates vary widely but range as high as $1.6 billion.

Interaction with the Local Population

The Taliban does have some small support among the local populace. It has “sponsored opium poppy cultivation in Afghanistan, and the jobs and income it provides for ordinary Afghans” generates political capital. The “governance is brutal and inadequate and not something most Afghans wish for,” but the Taliban has occasionally “reduced violence and overly-restrictive edits to generate acceptance by local populations.”

The Asia Foundation, a nonprofit organization based in the U.S., conducted a study in 2009 that found half of Afghans had sympathy for armed government opposition groups, primarily the Taliban. However, following the resurgence and rule of the Taliban, an “overwhelming majority surveyed said it was important to protect women’s rights, freedom of speech, and the constitution” and grew concerned.

Since establishing rule in Afghanistan in August 2021, the Taliban vowed to “respect women’s rights, forgive those who fought them, and ensure Afghanistan does not become a haven for terrorists as part of a publicity blitz aimed at reassuring world powers and a fearful population.” The group imposed a strict form of Islamic rule in the late 1990s, so many are skeptical of the promises, and the world has witnessed major setbacks in the Taliban’s approach to human rights.

Women are particularly concerned. A Taliban spokesman promised the Taliban “would honor women’s rights within the norms of Islamic law” but gave no specifics. Promises made in support of women’s freedoms were broken early on in the Taliban’s rule, validating most Afghan women’s fears that the Taliban never moderated their views. Annie Pforzheimer, deputy chief of mission at the embassy in Kabul from 2017-2018 said, “Afghanistan will no longer have women businesspeople, judges or other representatives,” and many female judges in particular, fear for their lives.

In September 2021, the Taliban announced an interim government made up of senior Taliban figures, “some of whom are notorious for attacks on US forces,” including one on a UN blacklist and another on the FBI’s wanted list. No women hold positions.

Girls above the sixth grade have been prevented from attending school since August 2021, and in December 2022, the Taliban banned women from working at NGOs, which has seen a catastrophic result of many organizations suspending aid work in the country. This came just weeks after the Taliban banned women and girls from attending middle school through college.

Across the country, Afghan citizens protested, and several people were reportedly killed by Taliban fighters firing into crowds. A Norwegian intelligence group report said the Taliban has targeted “Afghans on a blacklist of people linked to Afghanistan’s previous administration or U.S.-led forces that supported it.” Residents in Kabul, the capital, “say groups of armed men have been going door-to-door seeking out individuals who worked with the ousted government and security forces.” Between August 2021 and June 2022, “The UN Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) recorded at least 237 extrajudicial executions between the Taliban takeover.”

On top of these concerns, Afghanistan’s economy is collapsing; foreign aid, which composed a significant portion of the nation’s finances, has mostly been suspended since the Taliban took control in August 2021. Since the takeover, the economy has shrunk by nearly 30%, and 90% of the population suffers from food insecurity. Most Western countries have made girls returning to school a condition for restarting aid procedures and recognizing Taliban rule. Food prices have increased substantially, leaving many unable to afford food and at risk of malnutrition. Medicines that also came from foreign countries are in short supply, drastically reducing the capacity of the healthcare system.

U.S. Strategy

Although the U.S. toppled the Taliban in the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan, militants maintained a presence and continued to target the U.S.-backed Afghan National Security Forces. In 2017, the Trump administration announced it would send more troops to Afghanistan and appointed a top U.S. envoy for Afghanistan reconciliation, Zalmay Khalilzad, to help with peace talks between the Taliban and senior Afghan political figures.

Peace efforts suffered a number of setbacks throughout 2018 and 2019. In early 2020, the U.S. and Taliban negotiators “reached a preliminary deal that demanded a reduction in violence from the insurgent camp in exchange for a drawdown of U.S. troops in Afghanistan.” The Afghan government was not part of the agreement, but representatives from the Taliban, the Afghan government, and civil society met for the first time in September 2020, after nearly 20 years of war.

Although the UN Security Council reported the Taliban “‘shows no sign of reducing the level of violence in Afghanistan to facilitate peace negotiations,’” the U.S. began to withdraw troops in May 2021. The Taliban said it would not participate in any negotiations or conferences on the future of Afghanistan until foreign troops had left. By August 11, 2021, 95% of U.S. troops had been withdrawn, and the Taliban took complete control of Kabul on August 16. There were multiple reports that the Taliban had seized an array of American military equipment – including guns, ammunition, and combat aircraft – after overrunning Afghan forces.

Many have questioned whether the U.S. made the correct decision in withdrawing troops and ending military presence in Afghanistan. There are accusations of a “messy” withdrawal strategy and failures on the part of Afghan security forces. The U.S. deployed six thousand troops to assist with evacuating U.S. and allied personnel and to secure Kabul’s international airport since chaos erupted as thousands of Afghans attempted to flee the country.

The Taliban’s international legitimacy depends largely on these proceedings, especially given the Taliban’s struggles to run a government and deliver services to the people in the 1990s. While no country has officially recognized the Taliban as the legitimate government in Afghanistan, China and Russia have recently expressed interest in a relationship with the Taliban.

See the World Bank’s Afghanistan profile, Council on Foreign Relations’ timeline and overview, and overviews from the Counter Extremism Project and Stanford’s Center for International Security and Cooperation for more information.

Al-Qaeda and its Affiliates

Overview

Al-Qaeda first gained mainstream attention in the U.S. with its 1998 bombings of U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. On October 12, 2000, suicide bombers linked to al-Qaeda attacked the destroyer USS Cole as it was refueling in the Yemeni port of Aden, killing 17 American sailors and injuring 39. Osama bin Laden publicly took credit for the attack. According to the 9/11 Commission Report, the Clinton administration’s failure to respond militarily to the Cole attack emboldened al-Qaeda and led to a spike in recruits and contributors from the Gulf states. Since al-Qaeda’s September 11th, 2001 attacks on the Pentagon and the World Trade Center, the group has been considered one of the greatest threats to American security and values.

Areas of Operation

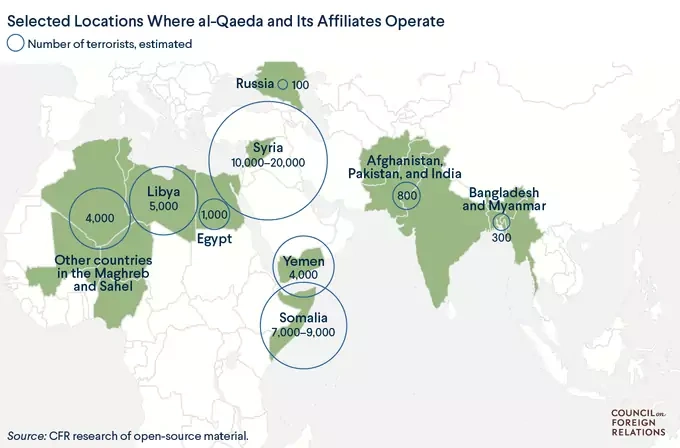

Al-Qaeda originated in Afghanistan and Pakistan, and its leadership is still largely based there. The group may have underground cells in dozens of countries and its main areas of activity include the Arabian Peninsula, Syria, East Africa, North and West Africa, and Central, South, and South-East Asia.

Between 2022 and 2023, there has been a significant rise of AQAP (Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula). In Yemen, AQAP focused its attention on the southern part of the country, targeting UN employees, “including the country director for the UN Department of Safety and Security,” and a convoy of Security Belt Forces.

Key Beliefs/Ideology

According to al-Qaeda scholar Katherine Zimmerman of the American Enterprise Institute, al-Qaeda aims to “unify the umma, Muslim community” and eventually build a caliphate, a political and religious Islamic state ruled by a caliph or chief Muslim ruler. Zimmerman claims that al-Qaeda’s attacks against the U.S. and the West were meant “to compel them to retreat from the Muslim world and end their support for state governments…Attacks against the West were always subordinate to the larger aims” of uniting the Muslim world.

Structure & Activities

In the aftermath of September 11th, 2001 and during the war in Afghanistan, al-Qaeda’s core leadership fled to Pakistan and regrouped in tribal areas along the Afghan border. Although U.S. Special Operations killed Osama bin Laden in 2011, and the subsequent U.S. drone program has killed top al-Qaeda leaders, the terrorist group remains intact. Al-Qaeda is a multinational operation with many affiliates such as al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, and Jabhat al-Nusra. However, a 2021 UN Security Council report noted al-Qaeda has suffered “severe leadership attrition, calling into question its ability to bring about a succession.”

While seeking refuge in Kabul, Afghanistan, al-Qaeda emir Ayman al-Zawahiri was killed by a targeted CIA attack in July 2022. Although al-Zawahiri’s death led the terrorist group to only its second leadership transition, “al Qaeda likely does not have an established succession plan to facilitate an orderly transition of power.” As of May 2023, al-Qaeda has yet to announce al-Zawahiri’s successor, although “veteran al-Qaeda operative Sayf al-Adl has become the group’s de facto leader.” Additionally, the future of al-Qaeda remains uncertain after counterterrorism operations diminished the ranks of senior leaders.

The group and its affiliates have a history of financing their terrorism with a variety of illegal activities, including ordinary crime and drug trafficking, as well as kidnapping and holding Western civilians for ransom. Some funds are procured via donations from wealthy supporters. In recent years, the groups have turned to “modern technology, social media platforms, and cryptocurrency” for more financial resources.

Interactions With the Local Population

In Afghanistan, the Taliban granted al-Qaeda sanctuary under cleric Mullah Omar, although there were tensions between the two groups. Al-Qaeda continues to cooperate with the Haqqani Network insurgent group in Afghanistan and Pakistan. With ISIS, a partnership was not out of the question, but ISIS rejected al-Qaeda’s authority and al-Qaeda criticized ISIS. Counterterrorism scholar Daniel Byman explained the two were essentially competing for leadership and the “soul” of the jihadist movement.

In areas it controlled, al-Qaeda imposed a strict version of sharia, a religious legal system derived from the Quran, Islam’s holy book. The group “became notorious for its sectarian suicide bombings against Shia Muslims in crowded markets and mosques, and for showcasing its grainy but gory execution videos… The group was equally brutal in suppressing populations over which it could exert power.”

Recruiters are primarily in the Middle East, and “patrol certain mosques known for extremist interpretations of Islamic texts,” while in Europe al-Qaeda “has sought recruits from those marginalized by society.” International recruitment efforts focus on young adults “who have not yet solidified their identities” and who are easily reached online, as online recruitment has grown sophisticated.

U.S. Strategy

In the wake of the September 11th attacks, the U.S. “relentlessly pursued Al Qaeda, targeting its leadership, disrupting its finances, destroying its training camps, infiltrating its communications networks, and ultimately crippling its ability to function.” The death of Osama Bin Laden also further diminished al-Qaeda’s influence.

However, the group has still become larger, more agile, and more resilient over the years. Thanks in part to the Internet, it is “geographically dispersed,” with tens of thousands of members operating in at least ten countries. There are four times as many related terrorist groups designated by the U.S. State Department as foreign terrorist organizations than there were in 2001.

The 2019 attack by a Saudi sleeper agent at a U.S. Navy air base in Pensacola, Florida – which killed three people and wounded eight others – “was a reminder that al-Qaeda is still able to mount international terrorist operations by working through one of its dedicated, highly capable franchises,” the Council on Foreign Relations explains. U.S. counterterrorism measures overall have succeeded in preventing another event like 9/11, but the challenge going forward will be balancing a number of competing national security challenges and diminished fiscal resources. An additional factor is the Taliban’s presence in Afghanistan, as the agreement between the Taliban and the U.S. included the Taliban committing to suppressing international terrorist threats.

See these overviews from the Counter Extremism Project, Stanford’s Center for International Security and Cooperation, and the UN Security Council for more information.

Islamic State (ISIS)

Known as Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS), Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), ISIL stands for the Arabic acronym “Daesh” or “Da’ish.” The Islamic State started as an al-Qaeda splinter group. It is a militant Sunni movement that aims to create a caliphate across Iraq, Syria and beyond. The group implements Sharia Law, rooted in eighth century Islam.

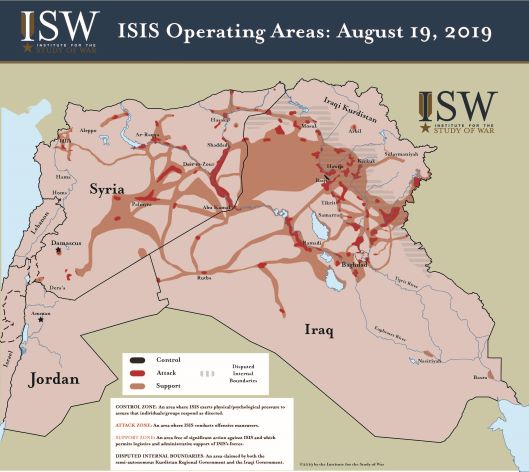

In 2011, the withdrawal of American troops from Iraq created a power vacuum, which ISIS filled. Throughout 2013 and 2014, with the onset of the Syrian Civil War, the group seized territory in Syria and Iraq. In 2014, the group “unilaterally declared a caliphate spanning eastern Syria and western Iraq” and named leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi its caliph. Over the course of 2017, U.S.-backed Iraqi forces pushed ISIS out of Iraq. In Syria, U.S.-backed Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces took over Baghuz, the last ISIS stronghold, and declared the territorial defeat of the Islamic State and the end of the caliphate in March, 2019.

Areas of Operation

ISIS’ main operations were in Syria and Iraq, but it has sympathizers around the world. A February 2021 report by the U.S. Department of Defense Office of Inspector General believes ISIS remains a “‘cohesive organization’” that continues to operate in Iraq and Syria and has declared provinces in Egypt, Libya, Algeria, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, Afghanistan, Mozambique, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, India, Pakistan, and Turkey. Although ISIS does not have the capability to launch large-scale attacks, it still has carried out attacks in Europe (such as vehicle attacks) and in Turkey, Morocco, Tunisia, the Philippines, Lebanon, Bangladesh, Indonesia, and the Palestinian territories. The graph below shows the shrinking geographical reach of ISIS’s control over a four year period.

Key Beliefs/Ideology

Ideologically, ISIS “identifies with a movement in Islamic political thought known as Jihadi-Salafism, or jihadism for short,” according to scholar Cole Bunzel. The jihadi strain “emerged in response to the rise of Western imperialism and the associated decline of Islam in public life.” Salafism is a Sunni Muslim doctrine that focuses on eradicating idolatry and considers Shi’a Muslims apostates. Although both ISIS and al-Qaeda adhere to jihadism, ISIS’s doctrine is more uncompromising than al-Qaeda’s doctrine.

Structure & Activities

ISIS’s leader was “the self-proclaimed caliph Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi,” who spent time in U.S.-run prisons in Iraq, where cells were organized. These cells, along with “remnants of former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein’s ousted Arab-nationalist Ba’ath party,” were high-ranking members. In a video released at the end of April, 2019, Baghdadi appeared for the first time in five years. He died in a U.S. special operation in late October 2019.

The U.S. Treasury Department described ISIS as “probably the best-funded terrorist organization we have confronted.” Extortion, robbery, human trafficking, and involvement in the oil industry brought plenty of funding to ISIS, although it lost significant amounts of income as it lost territory. However, without a physical caliphate, ISIS has no financial responsibilities to maintain a state, which allows it to exploit other revenue streams. ISIS “launders its cash reserves through investments in legitimate businesses across the Middle East such as hotels, car dealerships, and real estate.”

ISIS is skilled at using social media and the Internet to recruit fighters, both Arab-speaking Muslims in the Middle East and foreigners abroad. In the Middle East, ISIS “has capitalized on Sunni disenfranchisement in both Iraq and Syria.” Abroad, ISIS propaganda also continues to inspire lone-wolf attacks using means such as cars and homemade explosives. For this reason, ISIS-coordinated and ISIS-inspired attacks are a security threat around the world. Between 2014 and 2016, ISIS carried out or inspired 143 attacks in 129 countries, killing 2,043 people. An ISIS splinter group claimed responsibility for the 2019 Easter bombings in Sri Lanka that killed over 300 people.

The shift in government focus toward public health during the coronavirus pandemic appears to have allowed ISIS to increase its pace in attacks; in Iraq, “fighters have carried out increasingly sophisticated attacks targeting military checkpoints and Iraqi military housing.” In Syria, there has been “a steady campaign of assassinations, ambushes, and bombings.” In Afghanistan and Pakistan, Islamic State Khorasan (ISIS-K), which receives support from ISIS, has been responsible for hundreds of clashes with the U.S., Afghan, and Pakistani security forces and nearly 100 attacks on civilians since January 2017. A sworn enemy of the Taliban, ISIS-K adds additional security challenges for Americans in Afghanistan.

Interaction With the Local Population

ISIS’s state-building project to establish a caliphate in Iraq, Syria, and Libya was “characterized more by extreme violence than institution building.” ISIS imposed sharia law and “was notorious for killing civilians en masse, often by public execution and crucifixion.” In 2015, the United Nations reported it believed ISIS was holding 3,500 people as slaves, mostly from the minority Yazidi community.

Governments in Iraq and Syria “have struggled to reintegrate the tens of thousands of IS affiliates held in prison and security camps.” Camps for internally displaced people “have reportedly become ISIS’s new frontier for recruitment and radicalization,” as tens of thousands of former ISIS fighters live in these camps in the Levant, where they face starvation and exploitation.

U.S. Strategy

In 2014, the U.S. Department of State announced the formation of a broad international coalition of 74 countries to provide military support, stop ISIS’s finances, and address the humanitarian crisis. The U.S. and its coalition partners used air strikes and ground offensives led by the local U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces. Since the territorial defeat of ISIS, the international coalition is now dedicated to stabilization projects for liberated communities in the region.

In the fall of 2019, President Trump announced the withdrawal of troops from Syria, claiming “he wouldn’t allow U.S. troops to be in the middle of a longstanding feud between Turkey and Kurdish fighters.” Critics say the decision to withdraw without addressing the 20,000 ISIS detainees in north-east Syria could be dangerous and allow a resurgence of ISIS. Additionally, withdrawal without first guaranteeing the security of the U.S.’s Kurdish allies paved the way for a Turkish military offensive in Syria to seize territory held by U.S.-backed Kurdish forces. The Trump administration responded with the threat of economic sanctions on Turkey and emergency financial assistance to Kurdish allies. Meanwhile, the Kurdish officials quickly forged an agreement with the Syrian Assad regime to confront the Turkish military campaign, bringing “a U.S. partner in the fight against the Islamic State into alignment with Russia and Iran.”

Although U.S. troops under the Biden Administration remain diligent in combating ISIS in Syria, the terror group gained ground in central and southern Syria, where President Bashar-al-Assad’s regime remains in control. “In these regime areas, ISIS is back to controlling territory too, having recently defeated a six-week offensive by Syrian and Russian forces in a lightly populated stretch of the central desert.”

Given the ground ISIS gained during 2020, many U.S. military analysts believe ISIS poses a direct threat to regional governments and are concerned that further reducing U.S. troops in the region will “hinder the ability of the United States to maintain pressure against the group.”

See the Council on Foreign Relations’s backgrounder, or these overviews from the Counter Extremism Project and Stanford’s Center for International Security and Cooperation.