Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

By nature, police and communities are intertwined, and both are essential stakeholders in debates surrounding police reform. Dr. Karen Bartuch, Sgt. Sofia Rosales-Scantena, and Toni McIlwain joined The Policy Circle to discuss the role of police and the role of community involvement, and how citizens can help bridge gaps between communities and police officers:

According to Sir Robert Peel’s Nine Principles of Policing, the basic mission for which the police exist is “to prevent crime and disorder,” but it is also necessary to “recognize always that the power of the police to fulfill their functions and duties is dependent on public approval of [police] existence, actions and behavior, and the ability of the police to secure and maintain public respect.” This is because police officers are in a unique position, being “both part of the community they serve and the government protecting that community.” This position was the focus of the Obama administration’s President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, an endeavor to strengthen relations between law enforcement officers and the communities they serve, and it was at the heart of nationwide protests that erupted in May 2020 and sparked national debate over the role of police.

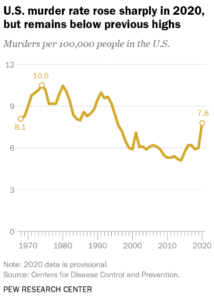

After over two decades of declining crime, there was a resurgence of homicides and gun violence in 2020. A July 2020 analysis of crime statistics by the Wall Street Journal found that reported homicides were up 24% for the first 7 months of 2020, compared with 2019. In 36 of 50 cities examined, homicides rose at double digit rates, including Milwaukee (37%) and New York City (23%). The FBI Uniform Crime Report shows a 30% increase in homicides for all of 2020 over 2019.

After over two decades of declining crime, there was a resurgence of homicides and gun violence in 2020. A July 2020 analysis of crime statistics by the Wall Street Journal found that reported homicides were up 24% for the first 7 months of 2020, compared with 2019. In 36 of 50 cities examined, homicides rose at double digit rates, including Milwaukee (37%) and New York City (23%). The FBI Uniform Crime Report shows a 30% increase in homicides for all of 2020 over 2019.

A May 2021 report from the National Commission on COVID-19 and Criminal Justice found that homicide rates declined from their 2020 peaks during the first quarter of 2021, but are still elevated compared to recent years. Aggravated and gun assault rates are also elevated. On the whole, 2021 saw homicide counts continue to climb, but at a slower pace than in 2020.

Crime maps indicate city centers, the sites of anti-police protests, did not experience these upticks; rather, the low-income neighborhoods outside of the city centers are seeing violence peak. These increases in criminality – and in some cases disregard for the law – have made life on the street for the average police officer much more difficult. Lockdowns and protests against the police sidelined the social institutions that tend to keep communities safe, leaving streets emptied “of eyes and ears on their communities.”

Why it Matters

Feeling safe and knowing that someone will help if you are threatened, attacked or your property is damaged is the foundation of confidence in oneself, in a community and in the world. Without safety people live in fear, and living in fear hinders well-being. People will not feel protected if they believe police are ineffective, or that they do more harm than good. At the same time, the role of police in protecting communities and stopping criminals has become more complex as officers are asked to respond to a broader breadth of community needs outside of law enforcement. Police need resources and support to carry out their duties, but they need to do so without using tactics that generate animosity. To understand how best to find this middle ground, let’s understand how law enforcement functions and is managed today.

Putting it in Context

In colonial times, law enforcement was a localized endeavor, carried out voluntarily by citizen groups, or sometimes by part-time officers privately funded by local communities. The Texas Rangers that patrolled Texas settlements in the 1800s became the basis from which state law enforcement agencies grew. In 1838, Boston established the first municipal police department, and was quickly followed by New York City, Chicago, New Orleans, and Philadelphia.

Police

There are over 660 law enforcement academies that train the officers who go on to work in almost 19,000 local, state, and federal law enforcement agencies. The bulk of these agencies are at the state and local level; state and local police departments employ over 930,000 people, with roughly 718,000 officers with power of arrest. In total, there are about 2.2 officers for every 1000 individuals living in the U.S.

Spending

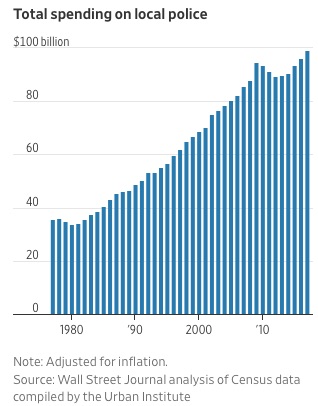

Spending on state and local police increased from $42 billion in 1977 to $115 billion in 2017 (adjusted for inflation), over 85% of which is local spending. Local spending on police “has outpaced the overall growth of city and county budget” over that time period, “rising faster than K-12 education, sanitation and parks and recreation.” Determining how much is spent on policing is difficult because funding comes from multiple sources; it is not enough to look at a city, county, or state budget alone for a full picture. In 2017, for example, Las Vegas spent less than 2% of its budget on police, but Clark County spent 15% of its budget on police; in Chicago that same year, the city spent almost 20% of its budget on policing, but Cook County only spent 2% of its budget.

Violent Crime & Deaths

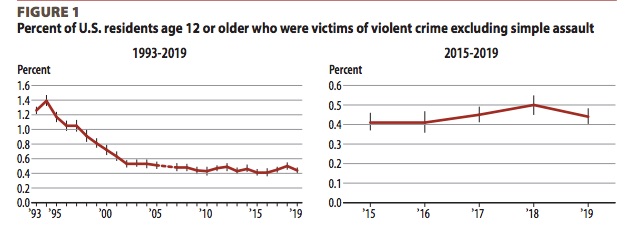

Based on the FBI’s annual report of serious crime and the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ annual crime survey, crime in the U.S. fell by 50%-70% between 1993 and 2018. Yet in 18 out of 22 surveys conducted between 1993 and 2018, at least 60% of respondents said they believed there was more crime in the U.S. compared to the year before. There are on average 8.25 million criminal offenses each year, resulting in about 10 million arrests.

As of mid-2022, the most recent statistics available are from 2020. Since 2015, law enforcement agencies have been transitioning to a detailed (but more complicated) format known as the National Incident-Based Reporting System. The new system involves financial and technical hurdles for many police departments across the country. Less than 60% of America’s local law enforcement agencies voluntarily submitted data in the new format, meaning national-level and state-level crime data is not universally available.

Crime statistics from the FBI for 2020 show that homicides rose 30% between 2019 and 2020, to 6.5 killings per 100,000 people. In the 1990s, this rate peaked at 9.8 per 100,000 people. Experts have pointed to the pandemic, fallout from social justice protests, and economic disruptions as possible causes, although overall crime fell by 6% between 2019 and 2020. Agencies across the country voluntarily submit data for these statistics. For 2020, 85% of eligible agencies submitted data; some missing include agencies in New York, Chicago, and New Orleans.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Crime Victimization Survey, through which U.S. residents self-report whether they have been victims of violent crime, reported 4.6 million total violent incidents in 2020, down from 5.8 million in 2019. In total, numbers have held relatively steady since 2010. It is important to note differences between self-reported crime and national statistics; based on comparisons to statistics from the FBI, about 40% of violent victimizations were reported to police in 2020.

According to the Washington Post’s police shootings database, 1,021 people were shot and killed by police in the U.S. in 2020. Of those civilians who lost their lives, 652 were reportedly in possession of a gun and 175 were reportedly in possession of a knife, while 60 were reported unarmed. An article published in The Lancet indicates deaths involving police may have been undercounted in the U.S. (by as many as 17,000 data back to 1980) due to discrepancies between independent tallies and government data of death certificates. Others note the independent tallies come from crowd-sourced databases, which may not be reliable based on specific criteria used in classification.

Although Black Americans made up 14% of the U.S. population in 2019, they accounted for 26.6% of arrests and 24% of individuals shot and killed by police. White Americans, at 60% of the population, accounted for 69.4% of arrests and 45% of individuals shot and killed by police. “A simple count of the number of police shootings that occur does little to explore whether racial differences in the frequency of officer-involved shootings are due to police malfeasance or differences in suspect behavior.” In light of population proportions, some point to these figures as proof of systemic racism and that Black Americans are more likely to be killed by police than White Americans. Others look at violent crime statistics that indicate Black Americans are more frequently involved in criminal incidents, which could mean they are more likely to have encounters with police.

Diving deeper into these statistics, the FBI estimates Black Americans were 39% of offenders in murder incidents in 2019, almost three times greater than their share of the population. Still others point to statistics that indicate Black Americans are even more likely to be victims of violent crime than offenders; at 14% of the population, Black Americans were 54% of murder victims in 2019.

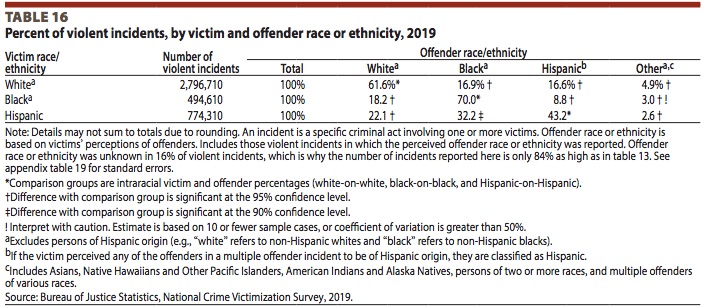

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ 2019 Crime Victimization Survey, violent criminal incidents with Black offenders and Black victims accounted for 70% of violent incidents involving Black Americans in 2019, a share much greater than their share of the population. In comparison, violent crimes with white offenders and white victims, at 62% of criminal incidents involving White Americans, is approximately equivalent to the population of White Americans. According to the 2020 survey, this rate did not significantly change over the course of the next year.

The chart from the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ 2019 Crime Victimization Survey examines the race and ethnicity of violent incident offenders and victims.

The Role of Government

Federal

The U.S. Constitution “established a federal government of limited powers. A general police power is not among them.” Congress does, however, have legislative powers that allow it “to enact legislation that relates to law enforcement matters.” Federal laws, such as those related to immigration, bankruptcy, civil rights laws, and tax fraud, apply in every state. Data collection on crimes and law enforcement is mainly done at the federal level to compile national statistics. The federal government is also the largest provider of law enforcement training, primarily through the Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers under the Department of Homeland Security. Finally, the federal budget includes provisions for supporting state and local law enforcement via justice assistance grants and public safety programs.

Federal Agencies

The Department of Justice (the DOJ) is the primary federal agency dedicated to public safety and controlling crime. The Attorney General (AG) supervises and directs the DOJ and its agencies, such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI); the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA); the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives; the Bureau of Prisons; and the U.S. Marshals Service.

For FY2021, total funding for the DOJ amounted to $55.3 billion. Law enforcement operations totaled $18.7 billion.

In total, there are 65 federal agencies and 27 offices of inspector general that employ full time personnel authorized to make arrests and carry firearms. These include the DOJ offices mentioned above as well as U.S. Customs and Border Protection under the Department of Homeland Security (DHS); the Park Service Rangers under the Department of the Interior; and lesser known security offices and details under the Departments of Commerce, Labor, and State, among others.

Congress

Congress can influence policing at the local level via the relationship between the DOJ and police throughout the country. Both the House and Senate Committees on the Judiciary provide oversight of the DOJ and DHS. In the Senate, the Judiciary Committee’s Subcommittee on Crime and Terrorism oversees the DOJ’s criminal division and most offices, including the FBI and DEA. In the House, the Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism, Homeland Security, and Investigations has jurisdiction over the Federal Criminal Code, sentencing, prisons, parole, and pardons.

State and Local

The Constitution gives authority over policing to the states. Each state and territory has its own legal and court system to handle criminal matters. State and local agencies make up the bulk of the almost 19,000 law enforcement agencies across the country, and local police departments employ the vast majority of all law enforcement officers, employing approximately 650,000 officers.

Each state has an attorney general who acts as “the chief legal officer of the state” and oversees law enforcement and reform. The attorneys general of each state and Washington D.C., and the chief legal officers of Puerto Rico, the Northern Mariana Islands, American Samoa, Guam, and the Virgin Islands are all members of the National Association of Attorneys General (NAAG).

At the local level there are municipal, county, tribal, and regional police departments that “uphold the laws of the jurisdiction, provide patrol, and investigate local crimes.” Sheriffs offices are granted authority by the state to enforce the state law at the local level in the more than 3,000 counties in the U.S. Police chiefs, who oversee departments, report to local elected officials such as a mayor, a city manager, or a city council.

Local police department officers have the most interaction with their communities. City, county, and municipal officers are those who respond to 911 calls, and monitor roadways and enforce traffic laws. Traffic stops are the primary way most people interact with law enforcement personnel. Most importantly, local law enforcement, like hospitals, operate 24 hours, 7 days a week; people turn to police departments when they do not know who else to turn to.

Current Challenges and Areas for Reform

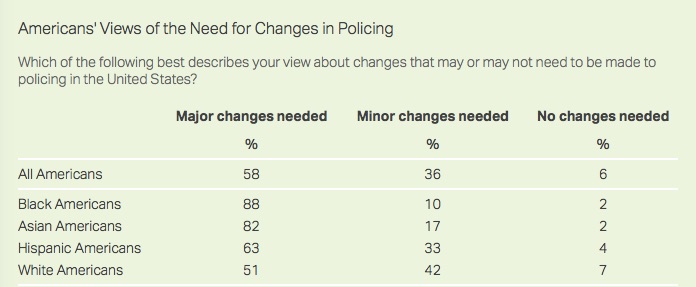

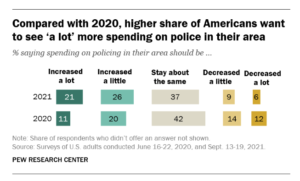

A series of incidents of excessive use of force in 2020, including the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Elijah McClain, sparked calls for more police oversight and reform. Mounting concern about violent crime in the U.S. has tempered some of these calls. In a July 2020 poll by Gallup, 58% of all Americans said that there were “major changes needed” for police reform. In mid-2021, 61% of Black Americans, 41% of White Americans, and 30% of Hispanic Americans reported having very little or no confidence in the criminal justice system. By late 2021, the share of adults who want more funding for policing in their area increased to 47%, up from 31% in June 2020.

Accountability

Misconduct & Excessive Use of Force

Use of force is one of the greatest concerns for many Americans. A June 2020 PEW poll found that only 35% of Americans believe the police do a good or excellent job of “using the right amount of force.”

Finding data to verify these assumptions is difficult. A 2017 Harvard study on police use of force and racial bias found “[d]ata on lower level uses of force…are virtually non-existent,” and “the analysis of police behavior is fraught with difficulty including, but not limited to, the reliability of the data that does exist.” The study examined data from New York’s City’s Stop and Frisk policy, the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ Police-Public Contact Survey, and officer-involved shooting data reported voluntarily from twelve police departments across the country. The main findings (p. 29-30) report:

“On non-lethal uses of force, there are racial differences – sometimes quite large – in police use of force, even after controlling for a large set of control designed to account for important contextual and behavioral factors at the time of the police-civilian interaction. As the intensity of force increases…the overall probability of such an incident occurring decreases but the racial difference remains constant. On the most extreme uses of force, however – officer-involved shootings with a Taser or lethal weapon – there are no racial differences in either the raw data or when accounting for controls.”

Federal legislation can establish a national use of force standard and a national database to keep better track of use of force data. Clearly defined legal standards means data can be objectively analyzed and paired with accountability measures. For example, federal grants can be tied to ensuring police departments adhere to standards and report data.

Mandating body cameras is a suggestion for ensuring reliable data and accountability. Live footage can guarantee police reports are accurate. It will also help target individual officers for wrongdoing as opposed to intense and lengthy investigations into entire police departments that may interfere in officers’ abilities to respond to community needs. As of mid-2022, seven states mandate body cameras for law enforcement personnel (Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Maryland, New Jersey, New Mexico, and South Carolina). About half of local police departments have acquired body cameras as of 2018. Urban Institute further breaks down each state’s body camera laws and regulations.

While body cameras have generally received wide-spread support, other means of equipping police officers have been called into question. The 1033 program authorizes the transfer of U.S. military equipment to state and local law enforcement agencies. This includes necessary ammunition and medical supplies, but also sometimes armed assault vehicles and weapons reserved for military conflict. Equipping local law enforcement officers properly is essential to their protection and that of their communities, but excessive weaponization of police has been linked to more cases of excessive use of force, and “exacerbates the gap between police and those they are supposed to serve.”

Unions & Collective Bargaining

Other barriers to holding police officers accountable for misconduct can sometimes be found in police contracts negotiated by unions. Police unions emerged alongside many other labor unions at the beginning of the 20th century. Although they initially enjoyed little public support, roughly two-thirds of American police officers are part of police labor unions today.

Police officers are government employees who require civil service protections in terms of demotions or transfers, layoffs or discharges, and pay and benefit determination. Additionally, due to the nature of police officers’ work, misconduct by officers can have more serious consequences than misconduct by other public employees. For this reason, state labor laws and Law Enforcement Officers’ Bill of Rights (LEOBRs) “provide police officers with due process protections during disciplinary investigations that are not given to other classes of public employees.” Collective bargaining by unions ensures these laws are included in police department contracts to protect officers who use their discretion in dangerous situations.

The concern is how collective bargaining contracts can affect departmental policies and even entire disciplinary processes. A study of 178 police union contracts around the country found that many “contain provisions banning civilian oversight, obstructing brutality complaints, inhibiting investigations in police misconduct, and restricting the ability of officials to track and identify officers with a pattern of civilian abuse.” Most frequently, contracts:

- Limit departments’ abilities to investigate civilian complaints, such as throwing out complaints that have been filed after a certain period of time following an incident;

- Mandate the destruction of disciplinary records after a certain period of time, which means officers that have been fired or have resigned over misconduct can be hired elsewhere with an apparently clean record;

- Limit the influence of a civilian oversight board, or prevent civilian oversight entirely;

- Dictate the disciplinary process police commissioners must follow and give arbitrators instead of police supervisors the authority to make final disciplinary decisions.

Despite having the authority “to compel cities, under threat of litigation, to invest in costly reform measures aimed at curbing officer wrongdoing,” even the DOJ still needs to work around union contracts. This makes interventions at the national level difficult. Instead, states can mandate transparency in police union contract negotiations. According to the Empire Center’s Ken Girardin, collective bargaining agreements are usually negotiated in private between union representatives, some elected officials, and certain police department officers. One argument for making collective bargaining open to the public is that groups who are most affected by the police – those who live in the communities police serve, and therefore are at the greatest risk of police misconduct – would be present at the negotiating table.

Qualified Immunity

Another barrier to accountability is what is known as qualified immunity, “a judicial doctrine that shields public officials, like police officers, from liability when they break the law.” Section 1983 of the Enforcement Act of 1871 strictly states that any state actor (like a police officer, a government employee) is liable for “‘the deprivation of any rights’” of citizens. In the 1960s, the Supreme Court judicially amended Section 1983 with the qualified immunity doctrine so the new standard of liability was the deprivation of “‘clearly established’” rights rather than “‘any rights’.”

Under the new terminology, “‘clearly established’” refers to precedent. This is another protection for officers who use their discretion in dangerous situations, but it also creates “a high and unnecessary bar” for proving officer wrongdoing. For example, when deputies in Georgia accidentally shot a 10-year-old child when aiming for a dog, the lawsuit the family filed was thrown out because the court “could not find precedent declaring this type of conduct unconstitutional.”

Ending qualified immunity would require federal legislation, which has been just one piece of the contentious debates in Congress. As of mid-2022, lawmakers have been unable to reach an agreement on police reform; bills passed the House but not the Senate.

States can take matters into their own hands. For example, they can bypass qualified immunity through their own legislation. Colorado’s SB217 “essentially bars government actors from using qualified immunity in state courts.” At a department level, liability insurance for law enforcement personnel, much like medical malpractice insurance for doctors, could offer police officers protection without shielding them from discipline. At the individual level, body cameras can protect officers from dubious claims while still holding them accountable for wrongdoing.

Reimagining the Police & Communities

Police Culture

“Police have become society’s de facto responders for a host of social problems – from homelessness and substance misuse to mental health crises, among others – for which they are both unprepared and ill-qualified to respond to.” With so much on their plates, law enforcement personnel doubt whether the public truly understands what they are asked to do and what they face on a daily basis. One PEW Research study found only 14% of police officers believe the public has a basic understanding of the risks and challenges they face on the job.

In addition to the inherent dangers of their profession, police officers “experience job-related stressors that can range from interpersonal conflicts to extremely traumatic events, such as vehicle crashes, homicide, and suicide.” Congress passed the Law Enforcement Mental Health and Wellness Act of 2017 in acknowledgement of the need for mental health resources for police officers, but whether this has made a significant difference is unclear; according to Blue H.E.L.P., officer suicides increased from 149 in 2016 to 239 in 2019, then fell to 174 in 2020 and 177 in 2021.

The FBI reported 89 officers were killed in line of duty in 2019, 93 were killed in 2020, and 129 were killed in 2021.This means more officers die by suicide annually than in the line of duty, and that is already considering suicide deaths are likely undercounted since there is no database that collects suicide-related data specific to law enforcement.

Low-risk encounters can inadvertently escalate when officers face heightened pressure, stressors, and trauma while on the job. Feeling overburdened, ill-equipped, and misunderstood creates a scenario in which officers can feel alienated from the communities they serve. Resources dedicated to helping officers develop techniques such as stress-coping skills, crisis management, and emotional intelligence training is one step towards addressing the “‘police warrior’” mindset and bridging gaps in community-police relations.

One method may be to redistribute officers across districts; a study from the National Bureau of Economic Research found more experienced officers use less force and make fewer arrests, but due to seniority-based process, districts with the most violent crime are staffed with less experienced cops that may be less effective at reducing that crime. Based on the assumption that senior officers are more effective at deterring crime, resolving situations, and exercising judgment due to experience, researchers determined crime would be reduced by almost 5% if senior officers were distributed across districts.

Sergeant Fred Jones notes that while “there will always be those that will not comply with the laws of society, and they will do anything not to be taken into custody,” emotional intelligence training plays an important role in police officers’ behavior, affecting how they treat others and themselves as they face these challenges on a daily basis (15 min):

Police Department Budgets

Spending on police has outpaced spending on education and community services in the past few decades. The premise behind the movement to defund the police “is that government budgets and ‘public safety’ spending should prioritize housing, employment, community health, education and other vital programs, instead of police officers.” Those who advocate defunding the police seek to redistribute a portion of funds that previously went to policing operations and correctional facilities. Instead of calling the police “to handle every societal failure,” funds and resources would instead be redirected to “supports for housing, mental health, addiction and employment” that could be more effective than arrests and jail time in solving underlying problems.

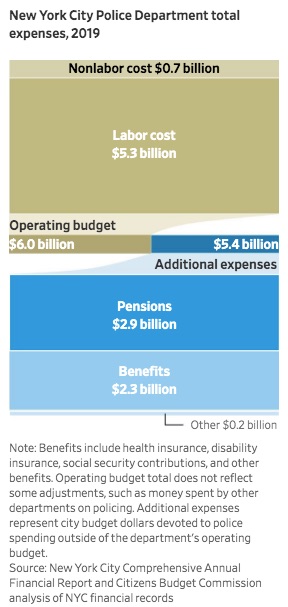

This relates to reducing the burdens on police officers’ plates, but police budgets are not that simple. State and local elected officials set police budgets, and it is usually police chiefs that need to work with the budget given to them. This includes accounting for “multiyear labor contracts negotiated with unions” and “pension obligations that last for decades,” which police chiefs have no authority to change. On average, two-thirds of police spending is dedicated to payroll (salaries and benefits), with more set aside for pensions. There are also costs of equipment, training, and day-to-day expenses, and unexpected costs can arise and eat into the budget as well. According to a WSJ analysis, “The 10 U.S. cities with the largest police departments paid out more than $1 billion in settlements and judgments from 2010 through 2014.”

This relates to reducing the burdens on police officers’ plates, but police budgets are not that simple. State and local elected officials set police budgets, and it is usually police chiefs that need to work with the budget given to them. This includes accounting for “multiyear labor contracts negotiated with unions” and “pension obligations that last for decades,” which police chiefs have no authority to change. On average, two-thirds of police spending is dedicated to payroll (salaries and benefits), with more set aside for pensions. There are also costs of equipment, training, and day-to-day expenses, and unexpected costs can arise and eat into the budget as well. According to a WSJ analysis, “The 10 U.S. cities with the largest police departments paid out more than $1 billion in settlements and judgments from 2010 through 2014.”

All of this makes cuts difficult, and the jobs of police chiefs to work within these constraints is made more difficult as well. In fact, by October 2020, 18 police chiefs from the U.S.’s 69 largest cities had “resigned, retired, been pushed out or fired,” citing protests for police reform and calls for budget cuts. On the whole, however, reporting from late 2021 indicates law enforcement staffing as a whole has been fairly stable.

Across the country from New York to Los Angeles, elected officials approved plans to cut police budgets, although “many of the cuts are cosmetic, temporary or represent a relatively small part of budgets.” Bloomberg CityLab data reports that 50 of the largest U.S. cities reduced their 2021 police budgets by about 5%, but that most of this was part of “broader pandemic cost-cutting initiatives,” and law enforcement as a share of expenditures was practically unchanged and even increased slightly in these cities. Cities including Minneapolis and Seattle paused these changes, and many more proposed funding increases for 2022 after rises in crime over the course of 2020. In New York City, current mayor Eric Adams ran on a platform that kept police funding stable.

Even with intentions to redistribute funds elsewhere, defunding the police could backfire. “When police command staff are presented with a reduced budget,” explains former FBI special agent Errol G. Southers, “[t]hey will cut the costs of the many programs police departments provide that are outside of day-to-day law enforcement,” mainly those that engage young people and police officers. This leaves few interactions between the community and the police, and therefore few opportunities to increase levels of trust.

A compounding issue is that drops in police-civilian contact are often followed by increases in crime, particularly in minority communities, according to Harvard economist Roland Fryer. In these communities and many others, response infrastructure and regular patrols mean that police officers are often the quickest to respond to 911 calls.

Public concern about violent crime in the U.S. has shifted attitudes about police funding, with decreasing support for defunding the police and increasing support for more local police funding.

Another possibility could be, instead of defunding the police, ensuring police first responders have the funds to equip them with the training and resources necessary to respond appropriately to all calls for help.

Others “are skeptical that existing police departments can ever be reformed” and believe “demolishing what is currently in place and starting from scratch” is the best option for transforming policing in America. They call not only to defund but to abolish the police. What this looks like is unclear. In June 2020, Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood closed down precincts in response to mass demonstrations, and police did not respond to calls coming from the neighborhood. A group of local business owners sued the city, claiming, “‘Seattle’s unprecedented decision to abandon and close off an entire city neighborhood, leaving it unchecked by the police, unserved by fire and emergency health services, and inaccessible to the public’ resulted in enormous property damage and lost revenue.”

On the opposite side of the country, Camden, New Jersey embarked on a campaign that actually did abolish the police department in 2013, but the city had a clear plan in place that “set about rebuilding the police force with an entirely new one under county control.” Prior to 2013, “the police were despised by residents for being ineffective at best and corrupt at worst,” and in one case five officers were charged with evidence planting, fabrication, and perjury. The transition took time and involved dismantling police union contracts and overhauling the system for rating officers’ performance. Today, the force still faces issues with transparency and high turnover rates, but the homicide rate and rates of excessive use of force have dropped considerably. For more on Camden’s transition, see this feature (5 min):

Community Policing

Community policing is “a police strategy that utilizes local partnerships and greater decision-making authority among street-level officers in an effort to solve community problems.” Focusing on partnerships between police and communities directly addresses the conditions that result in public safety issues, and has been found to reduce crime as well as fear of crime and increase public satisfaction and positivity towards police. The Department of Justice’s Community Oriented Policing Service saw an increase in funding for FY2022.

Implementing community policing does not always result in a department-wide mindset shift; instead, many departments treat “this model of policing as a one-sided transaction carried out by a few officers in a special unit or through sporadic events or meetings.” Such departments may sustain the “‘police warrior’” culture with tactics such as suppression style policing, which “casts a wide net over a high crime area” by flooding it with law enforcement personnel. In doing so, explains Josh Crawford of Pegasus Institute, “you catch the big fish that are committing the overwhelming majority of violent crime in that area. The problem is, you catch a whole lot of small fish and you catch a whole lot of things that aren’t fish at all.”

This tactic presents a challenge for police-community relations. While it may be effective in catching criminals and deterring crime, there is “a growing body of research that suggests that citizen evaluations of the police are more connected to the way the police interact with the public than to the effectiveness of policing on crime.” If a community does not trust the police, they may not be willing to cooperate and it may be more difficult for police to solve crimes. If police have low crime resolution rates, the community may be even less trusting, creating a cycle of police-community alienation. Captain Chip Huth explains how these tactics affected the Kansas City Police Department, and what happened when officers changed their systems and mindsets (10 min):

Within individual cities and communities, changing training priorities may help police officers and citizens find middle ground. Of the 700 hours of average training for police recruits, about 60 hours are dedicated to firearms training and 50 hours to self-defense training. In contrast, fewer than 30 hours are dedicated to community policing, which includes mediation skills, conflict management, and human relations. The New Haven Police Department incorporated community policing as a training requirement for recruits. Recruits completed community projects in the city, such as organizing after-school activities or playing sports with kids at local parks. After the projects, recruits noted their time “substantially altered their perception of the neighborhoods” they would be serving.

Social worker Derrick Jackson of the Washtenaw County, Michigan Police Department explains how problem-oriented policing works, and how even former convicted criminals can make positive changes in their communities when the opportunities exist (9 min):

Increasing communications is an important step police departments can take. Although studies suggest citizens do not frequently access police department websites, the ones who do have positive views of police effectiveness and legitimacy. This provides police departments with an opportunity to create user-friendly websites and engaging social media accounts that support community-police collaborations by disseminating information to the public as well as inviting the public to share information.

Communities in Action

Communities have taken steps to reimagine public safety, stepping up and doing their part to find ways to collaborate with law enforcement so as to best serve the needs of residents. Across the country, and even around the world, “community safety professionals” are taking it upon themselves to assist law enforcement through “youth outreach, conflict mediation, community patrol, and addressing low-level crime and disorder.”

Eugene, Oregon: CAHOOTS

When calls to the Eugene Police Department do not involve legal issues or risk of violence, dispatch operators will forward those calls to the medics and crisis workers that are part of the White Bird Clinic’s Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets (CAHOOTS) program. CAHOOTS, a collaboration between community social workers and police, has served as an alternative to police intervention since 1989. After receiving a call, a medic and crisis worker “go out and respond to the call, assess the situation, assist the individual if possible, and then help that individual to a higher level of care or necessary service if that’s what’s really needed.” On average, the clinic’s teams answer between 15% and 20% of the calls that come to the police, and have needed to call for police backup on less than 1% of calls. The estimated savings for the city of Eugene are around $8.5 million annually.

See more about CAHOOTS in this feature (5 min)

Greater Syracuse, New York: 211

The city of Syracuse and surrounding suburbs have struggled with high levels of poverty since the 1970s, but the area’s plan to end unsheltered homelessness has been fairly successful. Instead of calling 911, a “robust 211 provider coordinates outreach response and shelter referrals and provides diversion assistance on a 24/7 basis” under the Continuum of Care system. Through the process, “City and County staff, who are charged with addressing homelessness, pro-actively engage with police, fire/EMS, and other first responders, as well as the local healthcare, criminal justice, and child welfare system.”

Volunteers in Police Service

Volunteer programs can also help law enforcement agencies “fulfill their primary functions and provide services that may not otherwise be offered,” such as social media outreach, community meetings, surveys, and civilian oversight boards. In Fort Wayne, Indiana, and Memphis, Tennessee, faith-based institutions have partnered with local police departments for specialized academies that train clergy members on police activity, allowing them to serve as ambassadors that can help build trust and communication among the congregation, community, and police.

The Volunteers in Police Service (VIPS) program, managed by the International Association of Chiefs of Police and the Bureau of Justice Assistance under the DOJ, is a support system for police departments seeking to develop or expand citizen volunteer programs, or citizens looking to be more involved with their local law enforcement agencies.

Research is another integral component in helping law enforcement. Programs, volunteers, and community organizations are essential, but indications as to which services and systems are having the greatest impact is not always clear. This is where the University of Chicago’s Crime Lab saw an opportunity to assist. See what they’re doing (7 min):

Conclusion

The role of the police is to ensure the safety and security of those who uphold the law, and to protect and help communities from those who do not. But they need to do so without using tactics that disrespect civil liberties or generate animosity in the neighborhoods they serve. Policies and practices that focus on transparency and accountability can help bridge gaps between law enforcement personnel and communities. Individuals and communities that take responsibility for their safety can also foster mutual trust and understanding with law enforcement. Collaboration and opportunities to work together can make officers’ roles easier and make communities safer for everyone.

Thought Leaders and Resources

The Policy Circle would like to thank the following contributors for their assistance during the creation of this brief:

Brianna (Walden) Nuhfer, Stand Together Associate Director of Criminal Justice

Greg Glod, Americans for Prosperity Criminal Justice Fellow

Phil Andrew, Principal of PAX Group consultancy and former FBI agent and crisis negotiator

Quentella Enty, Director of Strategic Sourcing & Sustainability at KFA, Inc.

NCSL: Law Enforcement Overview

George Mason University Center for Evidence-Based Crime Policy

University of Chicago Crime Lab

National Initiative for Building Community Trust and Justice

Top Priority Podcast on Qualified Immunity with Greg Glod of Americans for Prosperity and Casey Mattox of Charles Koch Institute.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Find out what your state and district are doing about policing.

- Do you know the rates of crime in your community or state, or what social problems are prevalent?

- Start by investigating the FBI’s Crime Data Explorer or the DOJ’s Uniform Crime Reporting Statistics.

- Do you know how much your state or city spends on policing, and where these dollars come from (grants, police activity fines, philanthropy)?

- USA Today breaks down police department budgets in the 50 most populous cities in the U.S. – be mindful that some departments’ budgets are also funded by the county.

- What are your state’s policies regarding reforms such as body cameras or use of force definitions?

- How does your state or local law enforcement agency report data? Are they part of the Police Data Initiative?

- Does your community collaborate with law enforcement? Is there a community safety program?

- Has your city or state enacted community policing legislation?

- Do you know how law enforcement officers are trained in your state or community?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Are you familiar with your local law enforcement officers and their day-to-day roles?

- Who is your state attorney general?

- Do you know the role of police unions in your state?

- Are there organizations or programs in your community, such as faith-based organizations or after-school programs, that engage with law enforcement?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with law enforcement officers, first responders, faith-based organizations, local hospitals, community organizations, school boards, local businesses, and academic institutions.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, [email protected], for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policy makers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Volunteer with your police department or ask to participate in a ride-along to better understand police responsibilities.

- Attend a town hall meeting. Contact your local elected officials in advance to let them know you would like to discuss law enforcement.

- Ask your local officials to review local and county budgets, and ask them to invite public comment on budgeting to identify resources and funding gaps as well as understand what police obligations contribute to funding levels.

- Consider if there is an opportunity to bring a police-mental health collaboration to your community.

- Rethink policing by working with other stakeholders to define quantitative and qualitative measures for what successful policing looks like in your community.

- Consider assessing the components that are integral to the function of police departments

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.