Introduction

Case Study

Lelia Adams was born in a Nigerian village where she had to walk a mile daily to get water. She was a teenager when her father applied for the Diversity Immigrant Visa Program – “the Green Card Lottery.” Millions of applications are received yearly, but only 50,000 applicants are randomly selected.

Adams didn’t fully understand the lottery, and the idea of moving to the U.S. seemed like a dream. “I’d look up to the sky and just thought America was in heaven,” she said. “I’d seen airplanes up there. I’d never seen them land, so I thought it stayed in the heavens as a child.”

Lelia’s family was selected, and they moved to the U.S., with all five sharing a one-bedroom apartment. Due to a technicality, her mother was deported. Lelia was devastated but decided to attend law school to fight for her mother. Lelia graduated from Stetson University College of Law in 2009 and was admitted to the Missouri State Bar the following year. All the while, her mother remained in Nigeria.

Lelia filed for her mother’s case in 2012, and it took ten years to secure her visa back in the U.S. Lelia now specializes in immigration law to help other families, especially those who have had to leave a family member behind in their home country.

“I’m just so in awe of how she handles her life,” said Lelia’s mother.

Why It Matters

In mid-January 2024, President Biden stated that illegal immigration is a “crisis” and vowed to “seal the border with Mexico if Congress passed legislation that would give him emergency authority to do so.”

Many Americans agree that this crisis at the border is one of their top concerns. A recent Harvard CAPS-Harris survey found that immigration is now the top concern of voters, outranking inflation and the economy. In addition, 68% of all respondents and 50% of Democrats want stricter border enforcement.

Economics

Immigrants play an essential role in today’s economy and are projected to account for a substantial proportion of the U.S.’s labor force growth through 2030. According to the Bureau of Labor and Statistics, foreign-born workers comprised 18.6% of the civilian labor force in 2023, up from 15.3% in 2006. A complete 25% of all entrepreneurs in the U.S. are immigrants, and some of the largest U.S. companies, from Kraft to Tesla, were founded by immigrants. Ensuring skilled immigrants can pursue their ventures in the U.S. is just as important as ensuring immigrants have access to the education and training needed to advance their careers and build the skills necessary to meet the needs of the U.S. labor force.

To learn more about how high-skilled immigration drives innovation, watch this Kite & Key Media video :

Society

Foreign-born residents present both opportunities and social and political challenges for local governments. Particularly in urban areas with large populations of immigrants, policymakers and citizens play a role in community planning and ensuring communities do not become unequal or divided due to demographic changes.

Additionally, immigration is important to the census because it drives population projections that help report the impact of immigration on the future size and age composition of the U.S. population. The census has further implications with regard to redistricting and distribution of federal funds.

Border – Public Safety & National Security

Illicit Drugs

The U.S.-Mexico border extends 1,954 miles, spanning four states and about 26 land Ports of Entry (POEs).

U.S. Customs and Border Protection’s (CBP) Border Patrol and Office of Field Operations (OFO) together seized nearly 549,000 pounds of illicit drug substances nationwide in F.Y. 2023. CBP must interdict illicit substances across this vast and sometimes rugged expanse, both between and at POEs. Seizures of heavier, less-potent drugs like marijuana are down. In contrast, illicit fentanyl, a drug 100 times more potent than morphine, is up significantly: 480 percent higher at the southern border in fiscal year (F.Y.) 2023 compared to F.Y. 2020.

Crime & Gang Activity

Border arrests of migrants with criminal records hit an all-time high in 2023, causing concern among Americans about public safety.

Further, extensive media coverage of a “migrant crime wave” has garnered significant attention in this 2024 election year. New York City Police Commissioner Caban recently claimed there is a “migrant crime wave.” NYC police officials announced a Bronx raid and listed a litany of crimes likely committed by migrants, including robberies by men on mopeds. The Federation for American Immigration Reform compiled examples of migrant crime here.

It has been reported by the U.S. Customs and Border Protection that criminal convictions of illegal immigrants, including violent crimes, have seen a significant increase since 2020. Assault and battery convictions among noncitizens have risen by 502.8% from 2020 to 2023, and overall arrests of noncitizen offenders have jumped by 526.2% between 2020 and 2023.

Yet, some contend that the current data does not seem to support the recent comments about the crime wave, but crime data is fraught with delayed and inaccurate accountings. Some studies show the migrant population is not more violent than U.S. citizens. See a Stanford University study showing migrants were imprisoned at lower rates than people born in the United States. In 2020, a University of Wisconsin-Madison study noted that undocumented immigrants in Texas tended to have fewer felony arrests than legal residents. Other analyses conducted at both the state and federal levels find that immigrants—including undocumented ones—are less crime-prone than native-born Americans.

States far from the southern border are also reporting an uptick in what they label migrant-related crime. Montana is experiencing a 30% increase in illegal apprehensions this fiscal year compared to the entire northern border. Historically, unlawful border crossers mainly were Canadians, but last year, for the first time, they were comprised of primarily Mexican nationals. Migrants have been arrested for a range of crimes in Montana, including drug smuggling (an 11,000% increase in fentanyl seizures by anti-drug task forces in Montana since 2019 – reported by the Montana Attorney General) and human trafficking.

National Security

With illegal crossings of U.S. borders increasing (discussed below), many have become concerned about who is entering the U.S. and their intentions. The number of asylum seekers from China has also been trending upward since February 2023, with more than 52,000 recorded encounters in FY2023 and an additional 14,000 since the start of the new fiscal year. The U.S. is the largest destination for hopeful Chinese asylees, driven by a desire to escape Xi Jinping’s crackdown on civil society and individual freedoms ranging from expression to religion. We’ve seen a similar uptick in migrants from India following diminishing protections for Christians, Muslims, and Sikhs under Prime Minister Narendra Modi—in FY2023, nearly 42,000 encounters along the U.S. southern border were Indian nationals, an increase of 128% from FY2022.

With Europe tamping down on irregular migration, including through the recent passage of the E.U.’s Pact on Migration and Asylum, more refugees and migrants across the African continent are fleeing to Nicaragua and then trekking to the U.S. border on foot.

In a recent hearing of the House Committee on Homeland Security, Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Director Christopher Wray confirmed that there is an urgent national security threat posed by the nearly 1.8 million known “gotaways,” which are noncitizens who evade capture at a U.S. Border. Wray further confirmed that there is a rising number of individuals on the terrorist watchlist who have been apprehended crossing the Southwest border. Director Wray also confirmed joint terrorism task forces in all 56 of the agency’s field offices are occupied with threats coming across the border.

According to U.S. Customs and Border Protection officials in San Diego, militants associated with the Israel-Hamas war “may potentially be encountered at the southwest border.” The intel document shows various insignias worn by Hamas, the Lebanese militant group Hezbollah, and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad group. It urges CBP personnel to be on the lookout for military-age men wearing military gear and traveling alone at the border. No data is currently available that tracks

Putting it in Context

History

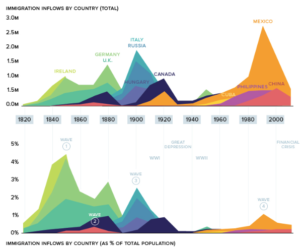

Immigration to the U.S. was low during the first half of the 19th century but slowly increased during the mid- and late-19th century, primarily due to famines in Europe and the U.S. victory in the Mexican-American War. While the United States “has long been considered a nation of immigrants…attitudes toward new immigrants by those who came before have vacillated over the years between welcoming and exclusionary,” and the influx of migrants saw a rise in anti-immigrant sentiment, first with the Know Nothing Party in the mid-1850s. Tensions surrounding immigration were prevalent in legislation such as the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, “the first and only major federal legislation to explicitly suspend immigration for a specific nationality.

See this comprehensive history of immigration with extensive data points by the Migration Policy Institute.

To manage increasing numbers of immigrants, the Immigration Act of 1882 levied a tax of 50 cents on all immigrants landing at U.S. ports and restricted who was allowed to enter the U.S., such as convicts and individuals deemed likely to become public charges. In order to enter, the federal government needed to determine whether or not the immigrant was capable of supporting her/himself and would not become a burden on society.

Restrictive immigration legislation during the 1920s included the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the National Origins Act of 1924, which placed caps on national immigration that favored Western Europeans and barred Asian immigrants altogether. Additionally, the Great Depression in the 1930s and the succession of two World Wars contributed to a sharp drop in new arrivals: most countries mistrusted foreigners during this time, and were unwilling to increase immigrant quotas, especially for impoverished refugees.

Today, U.S. immigration policies are rooted in the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, supported by Senator Ted Kennedy. This act established a system based on reuniting immigrant families and attracting skilled labor to the United States. Enacted during the era’s civil rights movement, it abolished national origins quotas, but established country origins; limits on immigration from Western Hemisphere countries were associated with an increase in unauthorized immigration from Mexico. Additionally, President Reagan signed the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) in 1986. The IRCA called for tougher border enforcement, penalized employers who hired unauthorized immigrants, and provided a path to citizenship for unauthorized immigrants. This legislation, however, did little to stem the tide of illegal immigration “because the strict sanctions on employers were stripped out of the bill for passage.”

See these timelines of the history of immigration in the U.S., from Sutori and Immigration History (provided by the University of Texas), and visualize two centuries of immigration to the U.S., from Visual Capitalist:

By the Numbers

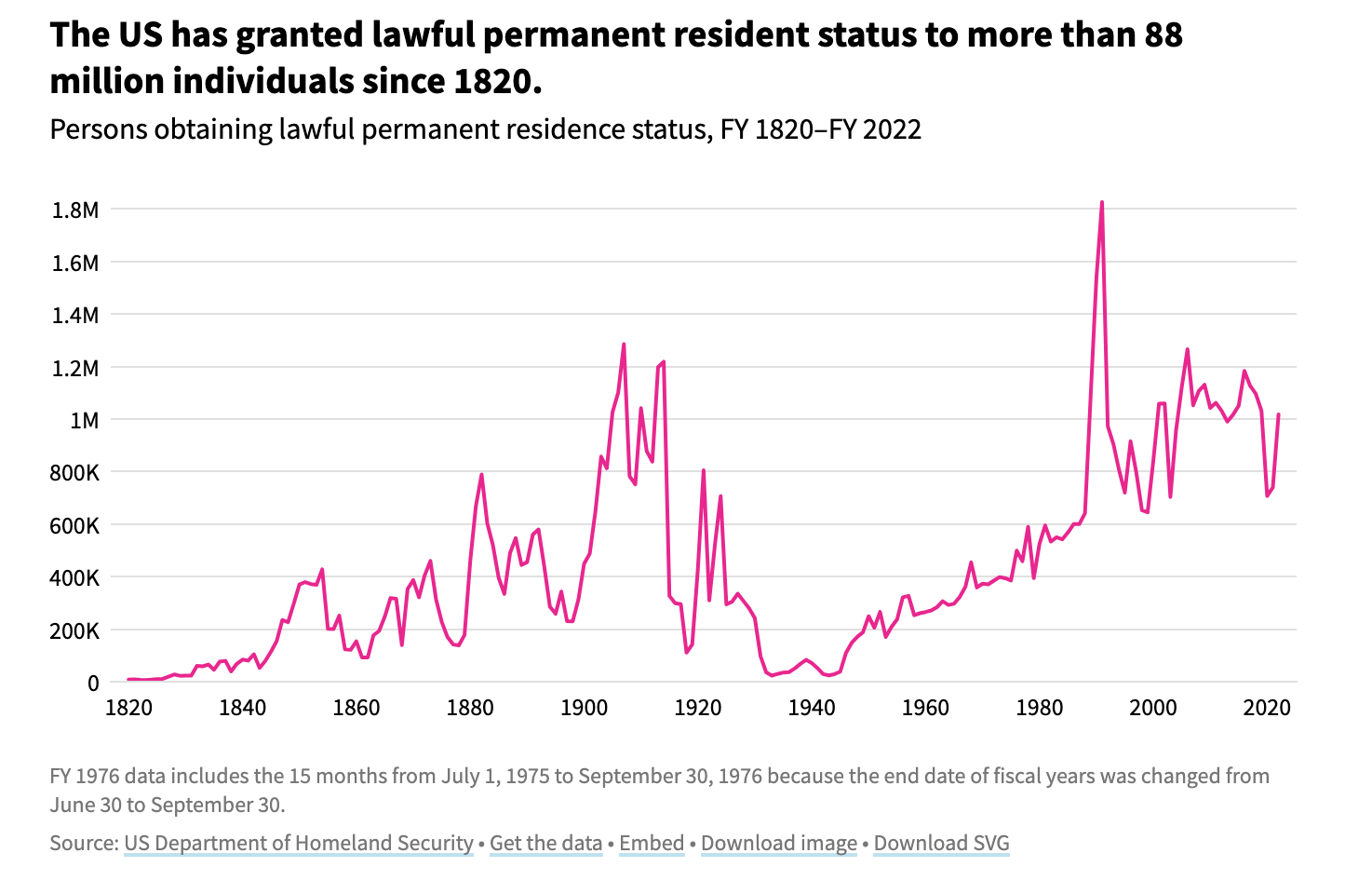

The United States welcomes more immigrants in total numbers (as opposed to a percentage of population) than any other country. After the 2008 recession, about 1 million people moved to the U.S. annually. As of 2022, 13.9% of the population was foreign-born, nearly three times higher than 1970. The most recent Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey in October 2023 showed that the total foreign-born or immigration population was 49.5 million.

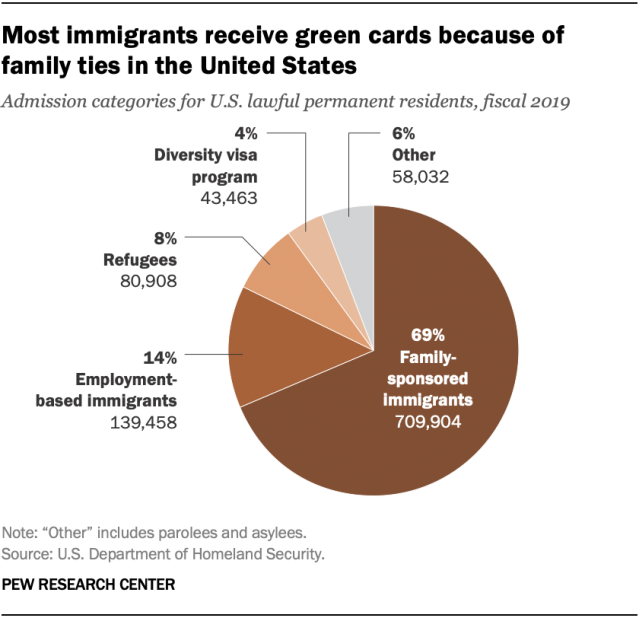

Green Cards

The U.S. issues over 1 million green cards, otherwise known as Permanent Resident Cards annually – half go to new arrivals, and half are renewals for expired green cards. A green card holder is someone who has been granted permanent residency in the United States, which is the authorization to live and work in the U.S. on a permanent basis. A green card holder can apply for U.S. citizenship after living in the U.S. for five years.

In FY2023 the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) “received 10.9 million filings and completed more than 10 million pending cases- both record-breaking numbers in the agency’s history.” This reduced the USCIS backlog by 15%.

Work Visas

In addition to green cards, in FY2023 the USCIS coordinated with the Department of State and issued more than 192,000 employment-based visas. H-1B visas are a “temporary visa category that allows employers to petition for highly educated foreign professionals to work in “speciality occupations” that require at least a bachelor’s degree or equivalent.” There is an annual cap for the H-1B visa at 65,000, with 20,000 additional visas for foreign professionals with a master’s degree or doctorate from a U.S. Institution. The cap was met for FY2023. This number also reflects that for the second year in a row, no available visas went unused.

At U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, the department that administers the U.S. immigration system, there are 1.5 million pending work-permit applications as of September 2023, up from about 650,000 in 2019. It took an average of 3-4 months to process an application in 2019; in 2021, it took 9-11 months, and is approximately 6.7 months as of 2023.

Refugees & Asylum Seekers

See Policy Circle Brief on Refugee Crises

“Under United States law, a refugee is someone who: Is located outside of the United States. Is of special humanitarian concern to the United States. Demonstrates that they were persecuted or fear persecution due to race, religion, nationality, political opinion, or membership in a particular social group.” – U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

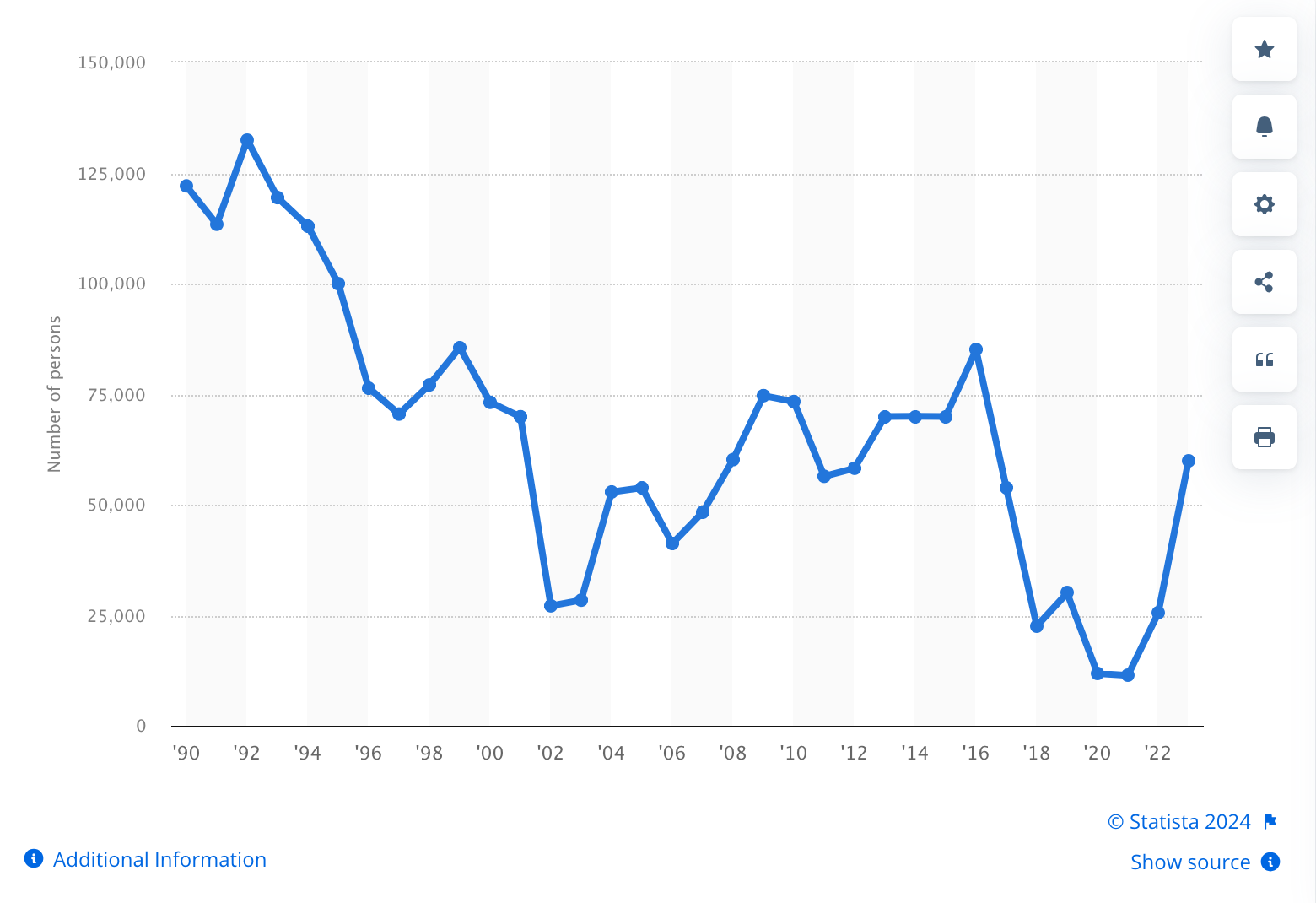

The U.S. admitted only 11,411 refugees in FY2021, the lowest number since the 1980 Refugee Act was passed. Low admissions is due in part to the pandemic (the U.S. admitted 12,000 refugees in FY2020 after suspending admissions) and partly due to low admissions caps set by the Trump administration prior to the pandemic. In FY2023 the USCIS interviewed over 100,000 refugee applicants, which is more than double the amount in FY2022. The USCIS admitted 60,014 refugees in FY2023, which was a significant increase from the 25,465 refugees admitted in FY2022.

According to Amnesty International, “an asylum seeker is a person who has left their country and is seeking protection from persecution and serious human rights violations in another country, but who hasn’t yet been legally recognized as a refugee and is waiting to receive a decision on their asylum claim. Seeking asylum is a human right. This means everyone should be allowed to enter another country to seek asylum.” As of May 2023, more than 1.3 million asylum applications were still awaiting processing.

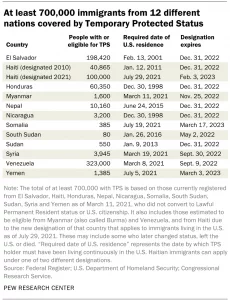

In addition to refugees, an estimated 700,000 immigrants have or are eligible for reprieve from deportation under Temporary Protected Status, or TPS, “a federal program that gives time-limited permission for some immigrants from certain countries to work and live in the U.S.” The program is for those who have fled designated nations because of conditions that make it dangerous to live there, such as war or natural disaster.

Of the 49.5 million immigrants noted in the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (October 2023), Census Bureau data indicates about 10.5 million of these immigrants are unauthorized, although some experts note self-reported Census data may not be accurate and the number could be as much as 20 million. Including immigrants’ U.S.-born children brings that total to 26% of the overall U.S. population.

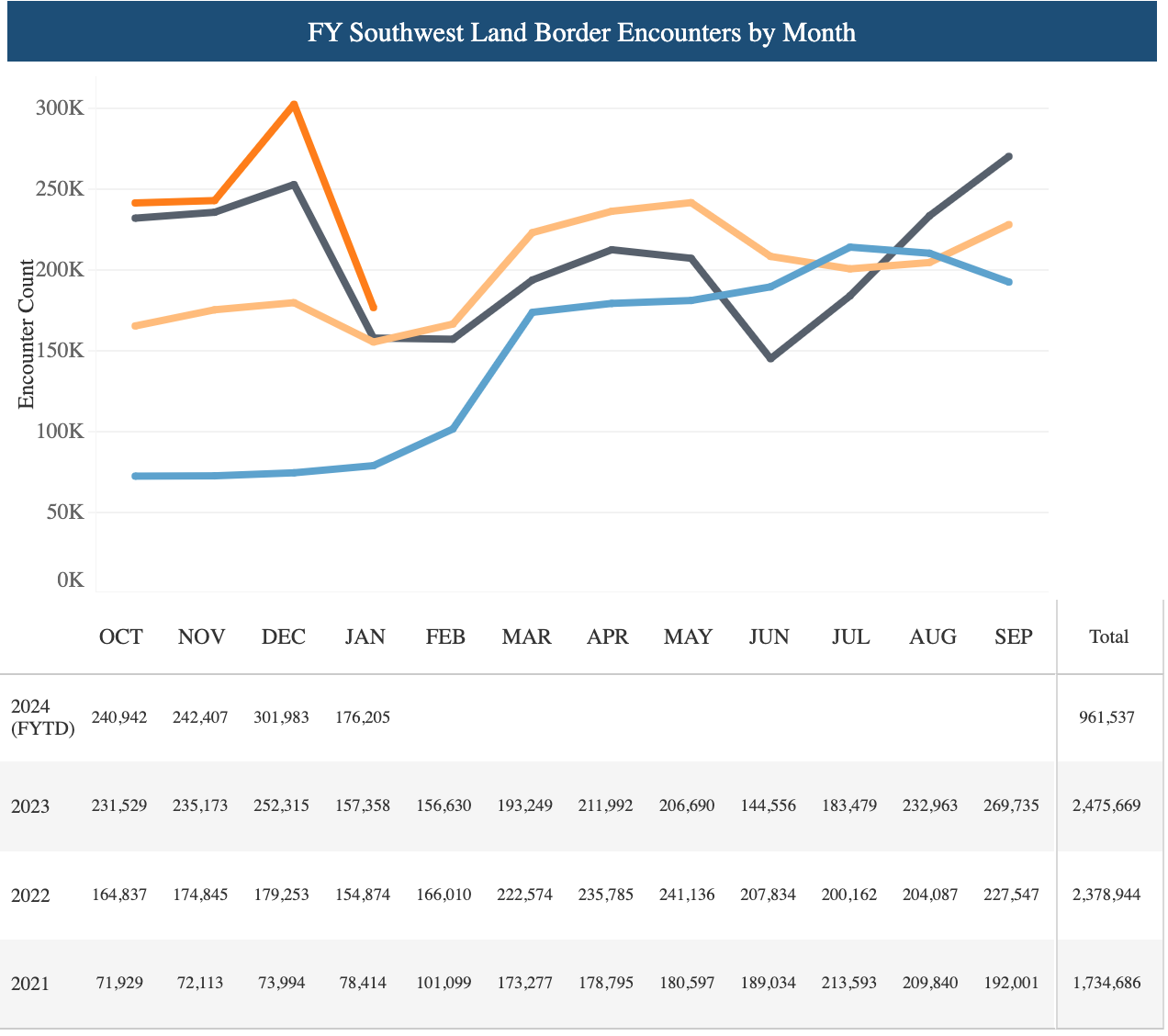

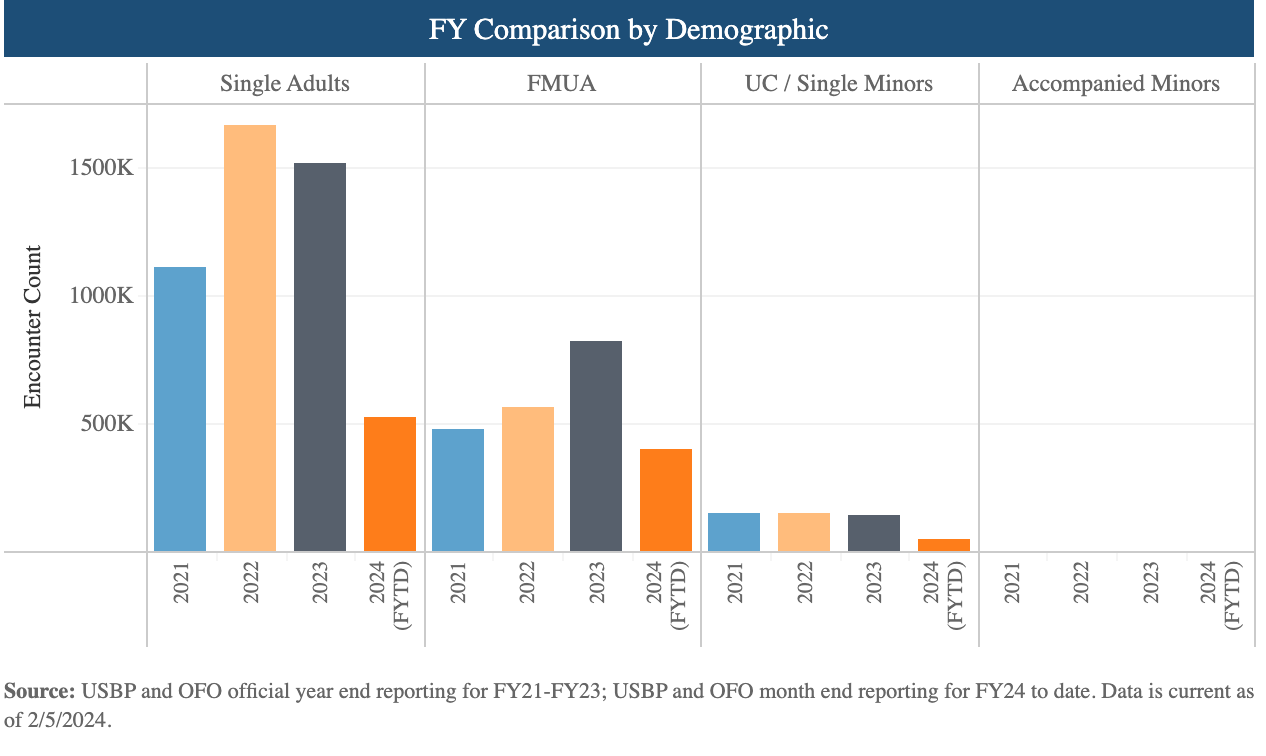

Illegal Immigration

In general, the number of unauthorized immigrants in the U.S. remained relatively stable from 2017-2021, however the rate of migrants coming to the U.S. southern border has reached historic levels. The U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) reported in FY2023, that encounters at the Southwest Border (SWB) increased over 40% since FY2021. The FY2023 SWB encounters totaled 2.47 million.

The majority of people crossing the border have been single adults, mainly young men looking for work. The encounters of single adults at the SWB total 176,205 in January of 2024 (latest measurements as of March 2024). To see a full breakdown of SWB encounters by year and demographic, see charts below:

Removal and Backlog

As one follows coverage of the current statistics, it is helpful to consider this terminology:

- Apprehensions: Migrants are taken into custody in the U.S., at least temporarily, to await a decision on whether they can remain in the country legally, such as by being granted asylum. Apprehensions are carried out under Title 8 of the U.S. code, which deals with immigration law.

- Expulsions: Migrants are immediately expelled to their home country or last country of transit without being held in U.S. custody. Expulsions are carried out under Title 42 of the U.S. code, a previously rarely used section of the law that the Trump administration invoked during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. The law empowers federal health authorities to stop migrants from entering the country if it is determined that barring them could prevent the spread of contagious diseases.

Illegal immigrants may face deportation from the country. Removal proceedings commence when the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) charges a foreign national with an immigration violation under Title 8 of the U.S. Code and files a Notice to Appear (NTA) in immigration court. OHS components may charge individuals at the U.S. border or within the U.S. interior with grounds of inadmissibility (e.g., attempting to enter the United States unlawfully) or deportability (e.g., committing certain criminal offenses or violating a nonimmigrant status or condition of entry). In spite of increases in funding and staffing, there is currently a backlog of 2 million cases in immigration courts.

Role of Government

Article I, Section 8, clause 4 of the Constitution entrusts the federal legislative branch with the power to “establish a uniform Rule of Naturalization.”

Specifically, Congress is responsible for crafting the laws that determine how and when noncitizens can become naturalized citizens of the United States. But control over naturalization does not necessarily mean control over immigration, meaning “the federal government is not explicitly granted a general power to exclude or remove noncitizens from the United States.” For the first century after the nation’s birth, many states enacted laws regulating and controlling immigration across their own borders. It was not until the late 19th century that Congress began to actively regulate immigration on a national level, with measures designed to restrict Chinese immigration.

Congressional committees most involved with immigration include the House Subcommittee on Immigration Integrity, Security, and Enforcement under the House Committee on the Judiciary; and the Senate Subcommittee on Immigration, Citizenship, and Border Safety under the Senate Committee on the Judiciary.

Today, U.S. immigration policy, set by Congress, is executed through a component of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) called U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). The agency seeks to “secure America’s promise as a nation of immigrants by providing accurate and useful information to our customers, granting immigration and citizenship benefits, promoting an awareness and understanding of citizenship, and ensuring the integrity of our immigration system.” Other agencies involved include U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) which combines “customs, immigration, border security, and agricultural protection into one coordinated an supportive activity,” and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) that focuses on border security and “the illegal movement of people, goods, and funds into, within, and out of the United States.” In the State Department, the Bureau of Population, Refugees, and Migration also plays a role, specifically in assisting refugees and displaced persons.

State and Local Level

The federal government is primarily responsible for enforcing immigration laws, but it may delegate some duties to local and state law enforcement; for example, states still exert influence over immigration policy through their power to issue or withhold state issued identification (driver’s licenses), state-level benefits and state-level cooperation (or lack thereof) with federal officials.

Undocumented immigrants are allowed to apply for driver’s’ licenses in California but not in Pennsylvania. Arizona permits police to question people about their immigration status, but Montana does not. Several states and municipalities that limit their cooperation with federal immigration policy have been labeled “sanctuary cities.” Lack of coherence across state and even county lines is a topic of contentious debate. To learn more about the role of state and local government in the development of immigration policy, visit the Immigration Policy Project or the Immigration Legislation Database.

Many states have enacted laws designed to help integrate immigrants into society. Efforts include legislation to support civic education classes to help immigrants pass the naturalization test, to fund immigrant integration programs that teach English, and to reduce licensing barriers that would permit educated immigrants to practice their professional skills.

Florida enacted SB 1718 into law in May 2023, which invalidated out-of-state driver’s licenses given to illegal immigrants, requires hospitals to quantify uncompensated care given to them, and, compels employers with at least 25 employees to use E-Verify to check new hires’ legal status. Many predicted this would cause a labor shortage and have a detrimental impact on the Florida economy.

Florida avoided those impacts by using the H-2A agricultural guestworker program, which lets farmers employ foreign guest workers for up to three years at a time if they’re able to navigate the program’s red tape.

Sanctuary Cities & Border Enforcement

According to the American Immigration Council, there is no legal standard definition of sanctuary policies. The current map of Sanctuary Cities can be found here.

The Center for Immigration Studies Studies Director Jessica Vaughan defines it this way, “These cities, counties, and states have laws, ordinances, regulations, resolutions, policies, or other practices that obstruct immigration enforcement and shield criminals from ICE — either by refusing to or prohibiting agencies from complying with ICE detainers, imposing unreasonable conditions on detainer acceptance, denying ICE access to interview incarcerated aliens, or otherwise impeding communication or information exchanges between their personnel and federal immigration officers.”

Case Study – New York City

New York City became a sanctuary city back in the 1980s, focused more on public safety because it allows undocumented immigrants to report crimes, seek medical help, and go to court — without fear they’ll be turned over to immigration authorities. After being a staunch advocate for continuing as a sanctuary city, NYC Mayor Eric is now calling for an overhaul of the city’s approach to illegal migrants.

New York hastily launched a new migrant reception system in the spring of 2022, and since then, more than 170,000 people have passed through it. “The unfortunate reality is that we’ve been getting hundreds of people a day every day for nearly two years,” Kayla Mamelak, a spokesperson for Mayor Eric Adams, said. “We’re out of space, and we’re out of money.”

More than 1 million illegal immigrants live in NYC (as of 2023) and cost the city an estimated $9.9 billion in taxpayer resources.

Case Study: Texas Border

In 2021, Texas Governor Greg Abbott launched the Operation Lone Star initiative and declared an emergency disaster over illegal migration and cartel drug trafficking in Texas, which gives him authority to deploy thousands of National Guard soldiers and state troopers to the border. In the last 2 years, the program has expanded to empower local law enforcement to jail migrants on trespassing charges through Texas Senate Bill 4. Funds have been used to build a section of border wall. The Texas legislature has supported the operation by increasing penalties for smuggling and authorizing local police to take on immigration enforcement.

As part of this Texas initiative, concertina wire was installed along the Rio Grande. U.S. Border Patrol cut through parts of the barrier. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton filed a lawsuit against DHS, claiming federal agents had illegally destroyed state property. A U.S. district court judge based in Del Rio sided with the federal government, ruling that Border Patrol agents didn’t violate any laws by cutting the wire. In January 2024, the U.S. Supreme Court ordered Texas to allow federal border agents access to the state’s border with Mexico, where Texas officials have deployed miles of concertina wire. The order did not explain justices’ decisions. For now, it effectively upholds longstanding court rulings that the Constitution gives the federal government sole responsibility for border security.

Senate Bill 4, which gives local law enforcement authority to enforce immigration laws, was challenged. U.S. District Judge David Ezra rejected the law, calling it unconstitutional, but a federal appeals court stayed that ruling, and the Justice Department asked the Supreme Court to intervene. On March 4, 2024, the U.S. Supreme Court extended a pause to determine the constitutionality of the law and is expected to make a ruling any day now.

Current Challenges and Areas of Reform

Various Viewpoints

Historically, opinions on immigration policy vary widely and fall along party lines. With the recent surge in illegal border crossings, more bipartisan approaches are being considered.

Open Borders Policy

This point of view favors allowing relatively free movement across national borders. Professor Bryan Caplan of George Mason University says this concept has different visions; it could be likened to how European Union citizens can travel between E.U. countries, but there could still be security measures like TSA in place. He explains, “The way I sometimes describe it is, ‘Unless you belong in jail, you can go where you want.'” Some support this approach for benevolent reasons based on the belief that America is a land of opportunity that should be open to all. In contrast, others support such a policy for economic reasons based on the belief that the U.S. economy faces a population problem. Open borders would allow people to take a job anywhere they can find one.

Increased Restrictions on Immigration

Others believe that our immigration policies should be more restrictive because levels of immigration have ballooned over the years. There is particular concern about the number of illegal immigrants living in the U.S. With so many immigrants living in the nation, it leaves many asking, “What…is the absorption capacity of the nation’s schools and infrastructure? How will the least-skilled Americans fare in labor market competition with immigrants? Or…how many immigrants can the U.S. assimilate into its culture?” An additional component to this is that most immigrants come to the U.S. to work, but they support family members back home, so much of their profits are invested outside of this country.

Benefits for Immigrants

Some argue that we do not do enough for individuals trying to make it in America and that we should provide Medicaid, food stamps, and welfare programs to illegal immigrants. Others express concerns about immigrants, such as whether immigrants will put additional pressure on welfare programs.

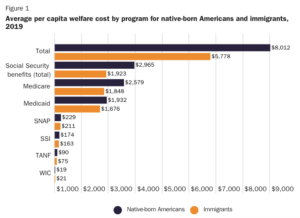

Evidence suggests that immigrants do not consume considerable amounts of welfare funding. A 2018 study by CATO Institute found that the average value of welfare benefits per immigrant (which included lawful permanent residents, guest workers, temporary migrants, refugees, asylees, and illegal immigrants) amounted to $3,718 in 2016, versus the $6,081 average value of welfare benefits per native U.S. citizen, meaning immigrants consumed 21% fewer benefits than native-born Americans on a per capita basis.

This held when the study was updated in 2022 with 2019 data; as of 2019, immigrants consume 28% less welfare and entitlement benefits than native-born Americans per capita, with the average welfare benefits per immigrant amounting to $5,778 and the average value of welfare benefits per native-born American amounting to $8,012.

The studies also found that while immigrants consume more than native U.S. citizens in some categories (SNAP and Medicaid in 2016 and WIC in 2019), this consumption is offset by the fact that native U.S. citizens consume significantly more than immigrants in Medicare and Social Security retirement benefits. (Medicare and Social Security are critical drivers of the U.S. debt – read more about these two programs in The Policy Circle’s Federal Debt Brief or Safety Net Programs Brief.)

Policies In-between

Many Americans support policies in between the ones outlined above, favoring generous but still restricted levels of immigration. For example, some support increasing the level of high-skilled immigrants, whereas the current system tends to favor family reunification. A widespread reform on both sides of the aisle is the mandatory nationwide implementation of E-Verify. This system allows businesses to verify a potential employee’s immigration status before hiring the individual. However, some in the business community and the agriculture community in particular say worker visa reforms must come ahead of an E-Verify requirement. The agriculture community faces hardship due to the slow visa processing times – immigrant agricultural workers frequently do not receive their authorization until after the growing season has passed.

These various viewpoints inform current opinions and challenges in the immigration debate. Of the few comprehensive reforms introduced in recent years, Congress has failed to reach a consensus or compromise and pass immigration legislation.

Efforts have mainly focused on:

- Securing borders (particularly the southern border with Mexico),

- Curbing and reforming illegal immigration, and

- Creating a merit-based immigration system.

Securing the Border

Operational Control

The U.S. Border Patrol strategy is Operational Control (OPCON), described as the ability to:

- “perceive and comprehend the operating environment.”

- “mobilize assets, infrastructure, and barriers to prevent criminal activity.”

- “and respond to and resolve any illicit cross-border incursions.”

Creating operational control of the U.S. land border with Mexico consists of deployed agents, fences, and technology such as sensors, cameras, and unmanned devices in areas where humans cannot provide timely coverage. Close coordination with partner agencies and foreign government partnerships will also help with intelligence gathering. The strategy for achieving operational control consists of a combination of enforcement tactics depending on the terrain.

Former President Trump planned to “build a wall” at the country’s southern border to curb illegal immigration and to enact policies that would deter migrants from coming across the border, such as the Zero-Tolerance Policy, which received backlash for separating children from families.

Still, many crossed the border without authorization because of long delays, and officials say the strain on staffing and resources is unprecedented. For a visual representation, see this Wall Street Journal graphic.

The Trump administration’s Migrant Protection Protocols (MPP) program, also referred to as “Remain in Mexico,” a joint effort with Mexico, was “one of the few congressionally authorized measures available to process the approximately 2,000 migrants who are currently arriving at the nation’s southern border daily.” Under the policy, families could live and work in Mexico while their asylum cases were adjudicated in the U.S. In response to the coronavirus pandemic, all pending MPP hearings were suspended, although people continued to be placed in the program.

The Biden administration terminated the program in mid-2021. Still, a U.S. District Court determined the termination was not issued in compliance with the Administrative Procedure Act and ordered Homeland Security to continue to enforce MPP until the program can be properly terminated. In Biden v. Texas, the Supreme Court ruled that the Biden Administration could end the Remain in Mexico policy.

The Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has been experiencing a “system-wide emergency” since 2019. After declining at the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, the number of migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border has been rising since April 2020 and was “on pace to hit a 20-year peak” in 2021. The higher-than-average trend has continued into 2022, as the graph from Customs and Border Patrol indicates.

CBP notes that the “large number of expulsions during the pandemic has contributed to a larger-than-usual number of migrants making multiple border crossing attempts, which means that total encounters somewhat overstate the number of unique individuals arriving at the border.” Over one-third of encounters in June 2021 were individuals with at least one border encounter in the previous 12 months, compared to an average rate of 14% between 2014 and 2019.

Based on a COVID-19-related public health order (Title 42), adults and families are being turned away, but the number of unaccompanied minors is surging. By law, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) “has custody and must provide care for” unaccompanied minors. The child border crossings are putting extensive strains on U.S. facilities, so much so that FEMA was sent to provide support. The support has helped relieve pressure and reduce overcrowding for unaccompanied minors, but overall, migration is still elevated. Reports of migrants being mistreated by border patrol agents have added to the attention on the southern border.

Title 42 expired on May 11, 2023, when the public health emergency for COVID-19 was lifted.

Poverty, gang violence, natural disasters, pandemic-related job losses, and even favorable rhetoric in the U.S. have all been cited as reasons for the surge in migrants. Most migrants are coming from the Central American countries of El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala (referred to as the Northern Triangle). Still, there has also been an increase, since 2021, of migrants from other countries, namely Ecuador, Brazil, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Haiti, and Cuba. Migrants from all other countries besides the Northern Triangle and Mexico are 20% of encounters as of mid-2021, up from 5% in 2018.

In June 2022, the Biden administration announced the Los Angeles Declaration on Migration and Protection, a non-binding migration agreement with Latin American countries that marks “a shift in the approach countries take to refugees and migrants amid unprecedented movement across the region.” Particularly for countries including Colombia, Ecuador, Panama, and Costa Rica that have hosted hundreds of thousands of displaced migrants, efforts will include building up asylum systems, providing more work visas, and increasing border security.

Immigration courts are also facing record-breaking backlogs in cases, with a backlog of 1.6 million cases. The overwhelming caseload has many concerned about whether immigrants will receive notice of their hearings so they know when and where they need to go. One solution is to hire more judges, but many argue this will not fix the issue as judges “require legal assistants, judicial law clerks, interpreters, and front-window staff – support roles that are critically under-filled[.].”

Immigration judges do not have summary judgment authority that allows them “to refuse to schedule cases that lack legal merit,” meaning “meritless cases clog the dockets.” Streamlined procedures that will enable asylum officers to decide cases or give judges summary judgment authority would save resources and time: “Cases that are granted would reduce the numbers being added to court caseloads and those eligible for protection would get it promptly, while those who are ineligible would be returned to their home country.” Legislation to make legal immigration faster and easier for those seeking opportunity and a better life would also close loopholes that encourage “the use of asylum claims as the preferred method to enter the U.S.”

The Entry-Exit System

An entry-exit system is our nation’s way of monitoring who enters and leaves the country. The 9/11 Commission recommended a biometric entry/exit system. The system has been approved and funded by Congress on at least six other occasions but has yet to be implemented nationwide. The U.S. utilizes a biometric system to track who enters the country at all points of entry, but exit capability is not deployed at the land border with Mexico. This is a large gap since about 45% of all entry inspections—land, air, or sea—occur at the southwest land border.

Why has the implementation been delayed? The proposed immigration entry-exit system would be based on digitized physical markers, like fingerprint images, photographs, or iris scans, and is estimated to be a 7 billion dollar investment. Additionally, implementation is hindered at the southwest land border due to space limitations and the potential for unintended economic impacts on the U.S. trade relations with Mexico.

The argument for installing a biometric exit system is that visa overstays account for a large percentage (possibly 40%) of illegal immigrants in our nation today. Biometric entry-exit systems can provide precise statistics and better tracking for people who have overstayed their visas.

DACA/DAPA Dreamers

Some argue that children of illegal immigrants should be awarded legal status because the illegal action taken by their parents was out of their control. Others argue that such an exception rewards and continues the cycle of illegal immigration.

The USCIS.gov provides this overview of DACA:

“On June 15, 2012, the secretary of Homeland Security announced that certain people who came to the United States as children and meet several guidelines may request consideration of deferred action for a period of two years, subject to renewal. They are also eligible for work authorization. Deferred action is the use of prosecutorial discretion to defer removal action against an individual for a certain period of time. Deferred action does not provide lawful status.”

In November 2014, the Obama Administration took executive action to shelter the parents of DACA-eligible children from deportation – Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (DAPA) – and expanded the eligibility requirements for DACA. DAPA has received scrutiny for its constitutionality and experienced several setbacks in court review. As a result, the policy has not been implemented. These policy measures outlined in DAPA were rescinded in September 2017, but the action was blocked by three district court judges and the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals.

In June 2020, the Supreme Court rejected in a 5-4 decision the Trump administration’s attempt to cancel the program but did not rule on the legality of the program itself. In July 2021, a district judge ruled DACA was unlawful because the executive branch does not have the power to grant reprieves to immigrants in the U.S. without authorization, meaning the president overstepped by creating the program.

In September 2023, a federal judge in the U.S. Southern District of Texas issued a ruling declaring DACA illegal. This decision does not affect the current protections offered to DACA recipients and their ongoing ability to renew their status. An appeal of his ruling will be heard by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, which previously ruled against DACA. If the Fifth Circuit rules that DACA is illegal, the case will likely be appealed to the Supreme Court.

DHS has said it is working on a regulation to codify a program for this purpose. Congress has made little progress in finding “a legislative solution for undocumented immigrants who arrived in the country as minors.” In the meantime, until other courts weigh in, the ruling prevents new DACA applicants from being approved, although current recipients can maintain and renew their status under the program.

See age, date and education requirements in the following video on DACA.

Read more about DACA, DAPA, and the court battle here.

Economics of Immigration

Two main options exist for reforming the immigration system: to increase legal immigration, so there are fewer cases of illegal immigration, and to authorize undocumented immigrants already in the U.S..

Research from the University of Pennsylvania Wharton finds that increasing legal immigration in the U.S. can have long-term fiscal benefits, while policies that legalize unauthorized immigrants could potentially increase government debt. The research concluded that legal immigration reduces the burden on native-born younger workers to provide for older retirees. As the children of new immigrants enter the workforce, this becomes a multi-generational effect. As detailed in The Policy Circle’s Federal Debt Brief and Safety Net Programs Brief, the current benefit formula for Social Security has benefits growing faster than revenues because today, there are fewer than three workers paying for each Social Security beneficiary, compared to more than 16 workers per beneficiary in 1950. Increased employment-related immigration could reduce this discrepancy in U.S. demographics.

In the case of offering legal status to unauthorized immigrants, there is a productivity boost to the economy in the short term. However, the research found that unauthorized immigrants earn about 50% less than citizens and lawful immigrants and are more likely to be older and, therefore, less likely to have children that will add to the labor force. With fewer earnings and a smaller second generation, legalization policies could cause output per capita to drop in the long run.

Wage Impact

Many have called on Congress to update wage protections to ensure U.S. workers compete on a level playing field. In 2013, when negotiating the Gang of Eight bill, the U.S. Chamber and the Department of Labor expressed disagreements over wages for immigrant workers and which industries would be included. The focus was heavily on temporary worker programs – low-skilled workers who would be brought in to fill jobs in construction, hotels, resorts, nursing homes, restaurants, and other industries.

During the latest economic recovery, the vast majority of the jobs created were part-time jobs and some analysis has shown that foreign-born workers were taking these jobs at a higher rate than native-born workers. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that in 2018, “foreign-born workers were more likely than native-born workers to be employed in service occupations” such as construction, maintenance, production, and transportation-related occupations, and “less likely to be employed in management, professional, and related occupations.” The difference in occupations often affects differences in wages.

According to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report, “over a dozen studies indicate (e) that immigration does reduce wages primarily for the least-educated and poorest Americans. It must be pointed out, however, that there remains some debate among economists about immigration’s wage impact.”

As the U.S. economy still recovers from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, fewer immigrants have impacted the labor force. The Wall Street Journal reports that industries with above-average levels of foreign-born workers are more likely to have high job opening rates.

Read here about shortfalls in wage requirements.

Professor Antony Davies of Duquesne University breaks down the economic effects of immigration (5 min):

Conclusion

Recent administrations have all endeavored to address U.S. immigration policy, but there have been few lasting changes, a testament to the complexities of immigration reform. Congress recently failed to enact legislation in spite of calls from both parties to address the current crisis. The Wall Street Journal explains the obstacles to changing immigration policies (6 min):

Ways to Get Involved/What Can You Do

Measure: Find out what your state and district are doing about immigration.

- Do you know the state of immigration in your community or state?

- See data points for your state regarding DACA participants.

- What are your state’s laws?

- Has your state or county enacted sanctuary policies?

- Is there a coalition or task force, or does one need to be formed?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Who are the members of coalitions or task forces in your state?

- Which committees do your elected representatives serve on?

- What steps have your state’s or community’s elected and appointed officials taken?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with law enforcement, first responders, faith-based organizations, local hospitals, community organizations, or local businesses.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, communications@thepolicycircle.org, for connections to the broader network, advice, and insights on how to build rapport with policymakers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Consider reaching out and asking your local business owners or your local Chamber of Commerce about the economic effects of immigration.

- You can find your local Chamber of Commerce here.

- Learn about your local businesses and if owners are first- or second-generation immigrants.

- Find out if your local schools or higher education institutions offer English as a second language classes.

- Explore USCIS’s Adult Citizenship Education Strategies for Volunteers to understand the basics of second language acquisition or the naturalization process.

- See if there are community-based organizations serving immigrants in your community with USCIS’s locator.

- Consider hosting a community dialogue to bring those with different opinions together to understand other points of view and strengthen the community.

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.

Thought Leaders & Additional Resources

- Dave Seminara at the Manhatten Institute’s City Journal

- Bush Center’s Immigration Focus

- U.S. Chamber – pro-business stance on immigration

- U.S. House Sub- Committee on Immigration

- U.S. House Sub-Committee on Border Security

- The Migration Policy Institute is a nonprofit organization that conducts nonpartisan research and analysis to help improve and develop immigration and integration policies

- The Center for Immigration Studies is a nonpartisan, nonprofit research organization that seeks to provide policymakers, news media, and citizens with accurate and reliable immigration information.

- Immigration Research, a free research library maintained by the University of Massachusetts Boston

- Immigration History, a timeline provided by the University of Texas, Austin

Key Terms

Migrate: To move to a new place

Emigrate: To leave one’s country to live in another

Immigrate: To come into another country to live

ICE: Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the agency that is known for detaining and deporting undocumented immigrants. A call to “abolish ICE” gained traction due to immigration policies such as the one that led to family separations.

Asylum: Protection given to noncitizens

Asylum seeker: An individual seeking international protection, whose claim has not yet been finally decided on by the country in which he or she submitted it. Asylum seekers apply at a port of entry when they seek admission or within one year of arriving in the U.S. (affirmative asylum) or if they are caught in the US illegally (defensive asylum).

Refugee: When an asylum seeker’s application for asylum is approved, he or she becomes a refugee. This means they have officially been deemed someone who has fled their country of origin and is unable or unwilling to return because of a well-founded fear of being persecuted. Refugees apply for admission generally from a “transition country” that is outside their home country. They are eligible to become lawful permanent residents one year after admission to the U.S. as a refugee.

Green card: Also known as a Permanent Resident Card, green cards allow people to live and work permanently in the US. Green card holders are referred to as “lawful permanent residents” (LPR). A Green card holder can apply for U.S. citizenship after living in the U.S. for five years.

Visa: A travel document placed in a passport that allows a traveler to travel to a port of entry (such as an airport or land border crossing) and request permission to enter the country. A visa does not guarantee entry, but indicates that an embassy or consulate has determined the traveler is eligible to seek entry. You can learn more about the different types of US visas here.

Wage Requirements: These are put in place to make sure employers do not take advantage of immigrants. For example, visa programs (like the H1-B or H2-B employment visas) require employers to prove they are not paying a foreign worker less than an American worker.

Birthright Citizenship/“Anchor babies”: The 14th Amendment grants citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States,” although there is debate as to whether this applies to any individual born on U.S. soil. Some lawmakers have pursued legislative efforts to define the 14th Amendment as applying only to babies born to a parent in the military, a lawful permanent resident, or a U.S. citizen.

Sanctuary Cities: There is no specific legal definition for what constitutes a sanctuary jurisdiction; however, such cities often do not allow municipal funds or resources to be used to enforce federal immigration laws, usually by not allowing police or municipal employees to inquire about an individual’s immigration status. Local law enforcement officials are not required to alert U.S. authorities about the immigration status of individuals with whom they come in contact.

E-Verify: An Internet-based system operated by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) in partnership with the Social Security Administration (SSA). It provides a link to federal databases to help employers determine employment eligibility of new hires and the validity of their Social Security numbers. Some states have passed legislation making its use mandatory for certain businesses. E-Verify is currently free to employers and available in all 50 states.

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.

Deep Dives

Want to dive deeper on Immigration? Consider exploring the following: