Introduction

Case Study

For the fiscal year 2022 the U.S. The Government Accountability Office reported $247 billion were spent in payment errors. Over the last twenty years, that amount has totaled to $2.4 trillion. Just a few years ago, an audit by the Office of the Inspector General revealed the Social Security Administration (SSA) in 2018 miscalculated the income of beneficiaries by nearly $1 billion and made $8 billion worth of improper payments. Part of the reason? Outdated technology. What does this misuse of funds look like for average citizens?

For Margaret Fitzwater of Cincinnati, Ohio, it was a letter from the Social Security Administration (SSA) in 2014 claiming that she had been overpaid by $27,000. In December 2018, 53 months later, Fitzwater finally got a hearing on her case, in which a judge determined she still owed the agency $30,000. In Connecticut, Bill and Bess Small, both 85, received similar notifications in March 2019. After two decades of overpayments and just after Bess was diagnosed with dementia, the SSA demanded the couple repay the total overpayment of more than $38,000. The agency admitted the couple are blameless, but denied the couple’s request that the demand for repayment be waived.

The Covid-19 Pandemic additionally brought on plenty of economic challenges, but the irresponsible use of COVID relief funds exacerbated the circumstances. In Broward County, Florida spent “$140 million in COVID-19 relief funds to construct a luxury hotel, complete with 30,000 square feet of pool decks, a rooftop bar, and an 11,000-square-foot spa and fitness center.” In addition, the federal government spends over $1.7 billion a year to maintain 77,000 empty buildings.

Taxpayers are the ones that suffer the consequences of improper payments. Little by little, the combination of mandatory government spending and the mismanagement of taxpayer money contributes more and more to the country’s debt and the struggles of its citizens.

Why it Matters

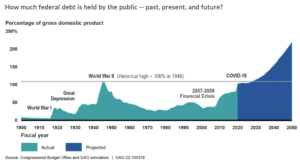

As the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) notes, the federal debt held by the public reached 97% of GDP at the end of 2023 (the latest measure as of March 2024). This marked the highest ratio since 1950, and the ratio has only continued its upward trajectory; by mid-2022, it hovered around 100% of GDP. “The projected growth in debt would dampen economic output over time and pose other significant risks to the nation’s fiscal and economic outlook.”

As the national debt increases, the likelihood that the government cannot pay a debt increases, which means treasury securities (bills, notes, and bonds through which citizens and non-citizens essentially lend money to the government) are riskier investments. When fewer people are willing to invest in government securities, there is also a risk of reduced economic growth, which can negatively impact household income.

Some economists say the debt should be sustainable as long as interest rates remain low, and note investors aren’t worried about the debt and continue to borrow. As interest rates rise, it will become more expensive for the government to borrow money because it will have to pay higher interest rates on the debt; relative to the size of the economy, required interest payments on the debt are projected to triple by 2050. Others argue that debts we accrue now will just need to be paid later, likely in the form of reduced benefits for services such as Social Security. The federal debt and federal deficit have impacts all Americans can feel.

Putting It Into Context

Key Terms

Federal Deficit

The deficit is the amount by which government spending exceeds the revenue it takes in each year. In other words, the deficit represents one year’s worth of “borrowing” by the federal government.

Federal/National Debt

The national debt is the “net accumulation of budget deficits,” or the total amount of money the U.S. government has borrowed. This includes public debt, when the public, the Federal Reserve, or foreign governments buy bills, notes, and bonds issued by the Treasury; and intragovernmental debt, which is money borrowed from one arm of the government to another, such as money from trust funds that are used to pay for programs like Social Security and Medicare.

Discretionary Spending

Discretionary spending is determined through annual appropriation acts authorized by Congress. A number of federal programs including defense, education, and transportation programs rely on the annual appropriation acts from the House and Senate Appropriations Committees. This money is considered “discretionary” because it is not what must be paid annually, but what Congress chooses to spend money on.

Mandatory Spending

Mandatory spending does not normally rely on annual appropriation acts and is instead dependent on legislation. This means mandatory spending is “essentially on ‘autopilot’ unless policymakers change the laws governing the program.” Mandatory spending includes the entitlement programs of Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, as well as smaller programs that involve payments to people and businesses (unemployment compensation, student loans, and retirement programs for federal employees and veterans).

History

The U.S. has been borrowing money since before it was an actual sovereign nation, when colonial leaders borrowed from France and the Netherlands to win independence from Great Britain during the Revolutionary War. This created quite a dilemma, as the Continental Congress did not have the power to tax citizens, and no taxes meant no revenue to pay off a debt. By 1790, the debt stood at $75 million (about $2 billion in today’s dollars), with a debt-to-GDP ratio of 30%. Thankfully, the economy was just starting out and growing well, which helped decrease the debt until the U.S. needed to borrow money to fight Britain again in the War of 1812.

In 1828, the debt was $58 million ($1.5 billion in today’s dollars). President Andrew Jackson referred to it as the “national curse” and sold off federally-owned land to help reduce the debt. While this succeeded, the debt only exploded again during the Civil War. The graph below illustrates this continued pattern of economic growth and debt reduction followed by recession and borrowing:

- Economic growth after the Civil War until World War I (when debt reached $25 billion, $334 billion in today’s dollars)

- Economic growth after WWI until the Great Depression, when debt grew under government expansion with the New Deal

- Economic growth until defense spending led to unprecedented levels of borrowing during World War II (when the debt-to-GDP ratio reached a new record of 113%)

- Economic growth after WWII until the 1970s recession and increased spending on social programs drove up the debt

- Economic growth in the 1990s that brought four years of straight budget surpluses starting in 1998 until the terror attacks on September 11, 2001 slowed things down, followed by borrowing to revive the economy after the Great Recession (CFR, History).

At the end of 2007, federal debt held by the public only stood at about 35% of GDP. The deficits from the bank bailouts and billions of dollars of fiscal stimulus during the Great Recession caused the ratio to double by the end of 2012. Even after the recovery, public debt-to-GDP ratio continued to climb to 78% by the end of 2019, and was just under 100% in mid-2022.

By the end of 2023, total U.S. debt had passed $33 trillion. Total debt-to-GDP ratio hovered around 100% from 2013 to 2019, and spiked to about 125% after spending in response to the coronavirus pandemic. This means the debt is larger than the U.S. GDP of roughly $24 trillion.

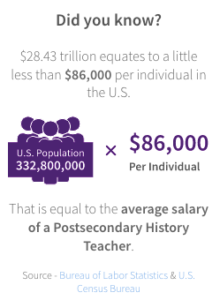

It may be difficult to fully understand the implications of such a large debt. The following graphic from USA Spending’s Data Lab breaks down $28.43 trillion (the U.S. debt at the end of 2021).

The Peter G. Peterson Foundation also helps puts $23 trillion into perspective here:

In 2009, spending cuts and a recovering economy boosted government revenue, which shrunk deficits. However, in September 2016 the budget deficit increased for the first time in five years to $587 billion due to increases in spending, higher interest rates on debt, and the growing number of Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security Recipients. In FY2022, the federal government collected just over $5 trillion in revenue and had expenses of $6.3 trillion, leaving a deficit of $1.4 trillion. This more than triples the 2019 deficit and more than doubles the previous record of $1.416 trillion spent in FY2009, due to increases in spending from healthcare costs, stimulus checks, unemployment compensation, and business rescue programs prompted by the coronavirus pandemic. In FY2021, federal spending was even higher $6.82 trillion, but revenues increased to $4.05, leaving a deficit of $2.77 trillion.

It took 204 years for our country to get to $1 trillion of national debt when it crossed that marker in 1983. We’ve gone on to add $9 trillion in debt in just the last decade. The debt is at a record high, and current projections show the debt exploding over the coming years.

Mandatory and Discretionary Spending History

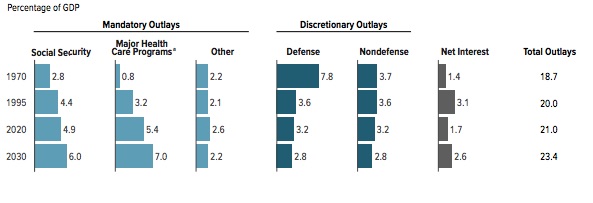

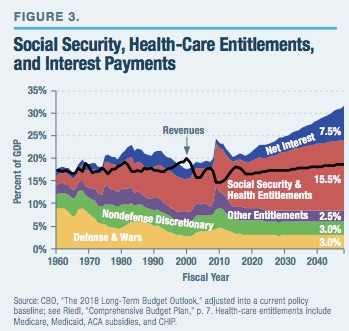

Mandatory spending has taken up a larger and larger chunk of the federal budget over time. The first expansion came with the Social Security Act of 1935, followed by the Medicare Act of 1965 that enacted Medicare and Medicaid. In 1962, before the healthcare programs, less than 30% of all federal spending was mandatory.

In 2022, mandatory spending amounted to $4.1 trillion, about 70% of total government spending and 17% of GDP. Between 2002 and 2021, mandatory spending outlays averaged 12.9% of GDP; increased spending in response to the coronavirus pandemic significantly impacted this.

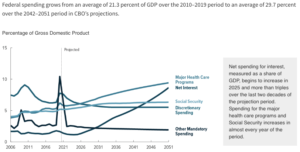

Meanwhile, discretionary outlays have shrunk, as evidenced in the Congressional Budget Office chart below. Discretionary spending averaged about 7% of GDP between 2002 and 2021, and jumped slightly to 7.8% of GDP in 2020.

Khan Academy further breaks down how these two spending sources have essentially switched in terms of total government spending in the last 50 years.

The Role of Government

What role the government should play in managing the debt is contested. Some policymakers place a lower emphasis on this problem, while some see the debt as a dangerous symptom of out-of-control spending. Those who view the debt as a serious problem tend to fall into two lines of thought: seek spending restraint and new rules to enforce it, or expand the power of the federal government by raising taxes and imposing controls on the industries contributing most, such as healthcare.

How Does the Government Contribute to Debt?

Congress, particularly the House of Representatives, holds the “power of the purse,” overseeing taxes and allocating public money for the national government.

Budgets, Bonds, and Borrowing

For every fiscal year, Congress must produce a budget resolution that sets the total amount of discretionary funding (which covers areas from defense and law enforcement to foreign aid and disaster relief) for that fiscal year. The House and Senate Committees on Appropriations are then responsible for separate appropriation bills through which program-by-program funding is determined. Mandatory spending, for programs like Medicare and Social Security, is not part of the appropriations process. It is automatic unless Congress alters underlying legislation; funding is based on parameters like eligibility and benefit formulas.

In addition to relying on revenues from taxes to fund its operations, the federal government borrows money and issues bonds. When the government borrows, “it borrows from people and businesses whose saving would otherwise finance private investment in productive capital…national saving, or the amount of domestic resources available for private investment, therefore declines” (CBO). This means borrowing can be counterproductive, as a more robust economy generates more economic activity and growth, and therefore the government has more to tax. This is why the economic recovery in 2009 had a tremendous effect on deficit reduction. The increased revenue for the government combined with a lower demand for government services, like unemployment assistance and other safety-net programs, helped to reduce the deficit.

The federal government issues debt in the form of Treasury bonds, which are purchased by individual investors, by foreign nations, and even bought back by our own federal government. In fact, the largest single holder of our debt is currently the Social Security Agency, at about 13%. Foreign investors hold over 40% of the total – primarily China and Japan, as each holds over $1 trillion. No other country holds more than $350 billion. See which countries hold the most Treasury securities here.

The Debt Ceiling

The debt ceiling “is the legal limit on the total amount of federal debt the government can accrue.” The debt ceiling was originally enacted in 1917 (during WWI) at $11.5 billion, and has since been increased by Congress and the President nearly 100 times. It increased from less than $1 trillion to almost $3 trillion in the 1980s, to $6 trillion in the 1990s, and to $12 trillion in the 2000s.

Debt ceilings mean the government is not allowed to issue any new debt. Since our federal government spending has significantly exceeded revenues in past years, it constantly needs to further increase the debt ceiling. Hitting the debt ceiling would mean at least a temporary default on obligations ranging from Social Security payments to veterans’ benefits. Defaulting would send both domestic and international markets into economic chaos, as it would mean the U.S. is no longer a safe investment.

The current options to address the deficit are a government shutdown, spending increases, or budget cuts. In response to the deficit, Congress consistently increases spending and the debt ceiling. Brian Riedl, Senior Fellow at the Manhattan Institute, explains that having a penalty default is important but can easily backfire: “If the penalty is too weak, it will not motivate lawmakers to overcome their strategic disagreement. If the penalty is too strong, the parties are more likely to repeal its enforcement without adding a deficit-reduction deal.”

This is key to understanding debts and deficits: reports on the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act reveal government revenue actually increased by 2% in the first seven months of FY 2019. But federal spending also increased by 7% during that period. Outlays in Social Security benefits, Medicare, and Medicaid all increased, dwarfing the revenue increases and reminding us that our nation’s deficits and debt will continue to rise without reigning in spending. No Labels breaks this down further:

Current Challenges and Areas for Reform

Main Drivers of Debt

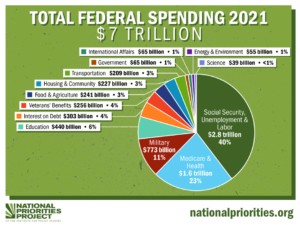

Changing demographics of an aging population, increasing healthcare costs, and rapidly growing interest payments are the main drivers of U.S. debt. The infographic below visually represents the 2021 federal budget. The majority of our government’s annual spending goes toward mandatory spending in the form of entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare. Without major reforms to these programs, our deficits and debt are expected to continue their upward trajectory.

USA Facts also breaks down government revenue and expenditures in this visualization.

Social Security and Changing Demographics

The non-partisan Peter G. Peterson Foundation, which seeks to increase public awareness of America’s pressing fiscal challenges, noted that, because of increases in life expectancy and the aging population of Baby Boomers, “the number of people age 85 and older is expected to triple over the next 30 years.” This also means growth in the entitlement programs (Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid) that serve this population and also play a key role in inflating the debt.

America’s aging population accounts for practically all the predicted spending growth in Social Security. Social Security is the single largest program in the federal budget. The CBO predicts the number of Social Security beneficiaries will rise from 64 million in 2019 to 97 million in 2049, and that spending will rise from 4.9% of GDP to 6.2% over this time period.

The problem is that the programs’ trust funds’ revenues are projected to grow more slowly than expenditures, meaning an eventual deficit. Estimates from an August 2021 report from the Trustees for the Social Security trust fund expect reserves to be depleted by 2034, one year sooner than estimated in April 2020. Starting in 2033, the program would have enough to pay about 75% of scheduled benefits. Slowed population growth, mortality rates, worker productivity during the pandemic, higher inflation, and reduced payroll tax revenue have all impacted trust funds. For more, see The Policy Circle’s Entitlements Brief.

Healthcare

In 2022 the U.S. spent $1.9 trillion, or 29% of GDP, on healthcare, and this is only predicted to grow. Healthcare spending includes Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and Affordable Care Act subsidies. Medicare alone accounts for over 20% of all national health spending. As the population ages, more Americans will qualify for federal healthcare programs, which are already straining against fiscal challenges. Growing costs of healthcare per person accounts for ⅔ of predicted spending growth. As the population ages, more Americans will qualify for federal healthcare programs, which are already straining against fiscal challenges. The U.S. spends far more on healthcare per capita than other advanced countries but does not see better results. Without reforms, these programs – and their budgets – will continue to grow unchecked to bear the increased cost of supporting more people who will also likely require more health care as they age.

In 2022 the U.S. spent $1.9 trillion, or 29% of GDP, on healthcare, and this is only predicted to grow. Healthcare spending includes Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and Affordable Care Act subsidies. Medicare alone accounts for over 20% of all national health spending. As the population ages, more Americans will qualify for federal healthcare programs, which are already straining against fiscal challenges. Growing costs of healthcare per person accounts for ⅔ of predicted spending growth. As the population ages, more Americans will qualify for federal healthcare programs, which are already straining against fiscal challenges. The U.S. spends far more on healthcare per capita than other advanced countries but does not see better results. Without reforms, these programs – and their budgets – will continue to grow unchecked to bear the increased cost of supporting more people who will also likely require more health care as they age.

Experts have long pointed to the system’s waste, estimating about 30% of total healthcare spending “goes to unnecessary, ineffective, overpriced, and wasteful services.” Estimates of total waste range from $600 billion to almost $2 trillion, or 17%-53% of the $3.6 trillion spent annually on healthcare.This does provide many opportunities for lowering costs. Alternative payment arrangements and more visibility in healthcare costs are common reform ideas that go beyond simply clamping down on costs, which would risk shifting costs to other parts of the healthcare system and making access to healthcare more difficult for intended beneficiaries. For more on reform options, see The Policy Circle’s Healthcare Brief.

The Manhattan Institute’s Brian Riedl (2019) breaks down these two main drivers (5 min):

Interest Payments

In 2022, interest payments amounted to $475 billion – the highest dollar amount ever. As a percent of GDP, interest payments are projected to double between 2021 and 2031. The Federal Reserve has been keeping interest rates low in response to the coronavirus pandemic, but inflation pressures are prompting the Fed to consider raising rates. In fact, by 2049, interest costs are predicted to be twice as much as the average government spending on research and development, infrastructure, and education combined. Projected borrowing will also increase interest. Many foreign investors hold Treasury securities, and so increasing interest outlays results in increased payments to foreign investors, meaning a reduction in household income.

Wasteful Spending

The vast amounts of money that come from entitlement programs and discretionary spending – the kinds of spending that are planned for – can sometimes dwarf the spending that is not planned for. But this does not diminish its importance. Improper payments are “payments made by the government to the wrong person, in the wrong amount, or for the wrong reason.” Improper payments can stem from an inability to access or verify data that could help determine whether recipients should receive payment, including death data or financial data. Mistakes inputting, classifying, or processing data can also lead to improper payments. Too many large programs are difficult to manage and keep track of and can result in spending excesses. See The Policy Circle’s Poverty Brief for more on these programs.

Besides improper payments, general waste is also a little known but large problem, particularly in year-end waste when the federal government goes on a “use-it-or-lose-it year-end spending spree” because agencies know that if they leave significant balances in their accounts at the end of the fiscal year, Congress may reduce their budget in the future. Open the Books investigates spending at the local, state, and federal levels, and has documented hundreds of examples of wasteful government spending from end-of-year furniture purchases to improper unemployment insurance payments.

Addressing Crises

Similar to the 2008-2010 stimulus legislation to recover from the Great Recession, but on a much larger scale, the federal government put together a series of relief bills in March 2020 to combat the economic fallout of the coronavirus pandemic. The three pieces of legislation, including the $2 trillion Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, are meant to provide billions of dollars in credit for struggling industries, public health support, direct cash payments to Americans, and a significant boost to unemployment insurance. Even with $2 trillion already committed, lawmakers are still considering taking action on a fourth phase of legislation.

Between October 1, 2019 and March 1, 2020, the U.S. budget deficit for FY2020 was already up to $625 billion. Although necessary to address the current needs of the economy – the small businesses struggling to stay afloat as social distancing affects their operations and the everyday Americans who have lost their jobs because they cannot be done remotely coronavirus spending pushed the 2020 fiscal year deficit to just over $3 trillion, more than triple the 2019 deficit and more than double the previous record of $1.4 trillion record set in 2009.

For the present, says Professor William D. Lastrapes of the University of Georgia, the government can afford to focus on the nation’s public health and mitigating the economic harms as long as fiscal institutions and the long-term productive capacity of the economy are secure. But, eventually, it will be essential to look to debt-reducing measures.

Debt-reducing Measures

Generally speaking, there are various methods a government can use to attempt to reduce debt, but none are without controversy. Some examples that governments have used in the past include the following:

Interest Rate Manipulation

Governments from the United States to the European Union to the United Kingdom have all kept interest rates low to help their economies in the past. When interest rates are low, people and businesses can easily borrow money to spend on goods and services that generate jobs and tax revenue to stimulate the economy. In recent years, “persistently low interest rates have provided a fiscal cushion of the U.S. and kept the deficit from growing even faster,” but the Federal Reserve’s desire to keep rates at record lows at least through 2023 to support economic growth in the wake of the pandemic is encountering the challenge of rising inflation. Additionally, keeping interest rates close to zero does not in and of itself solve the problems of mounting debts and deficits.

Focus on Trade

Nations can also rely on increases in exports and production to reduce their debt burdens, as focusing on trade can also contribute to economic growth. Between 2003 and 2010, for example, Saudi Arabia’s oil production and exports helped reduce its debt from 80% of GDP to just over 10% of GDP. Boosting economic growth, and therefore revenue, had been a goal of the Trump Administration in renegotiating trade deals with Mexico, Canada, and China. See The Policy Circle’s Tariffs Deep Dive (link to come) for more on these trade deals.

Bailouts and Defaults

Bailouts and defaults are more drastic measures when it comes to debts and deficits. A bailout entails debt forgiveness. Jacob Goldstein, host of the podcast Planet Money, says a bailout gives a country “time to get its act together, start growing again, and pay down its debt.” This is what the European Union did during the global financial crisis when it bailed out Greece, Ireland, and Portugal by lending them more money. But long-term, deeper economic troubles can make such loans a bad idea.

When a country can’t repay, it ends up defaulting. Defaulting on a debt includes missing or delaying a payment, or restructuring payments to creditors. This happened to Greece: the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the EU contributed to the country’s bailouts in 2010 and 2012 but its debt was too deep for the loans to make a sustainable difference. In 2015, Greece became the first developed country to default to the IMF, which led to a third bailout for the country that year. Russia, Argentina, and Pakistan have all defaulted on loans since the 2000s. Defaulting impacts current investors and does little to boost confidence for future investments, which can mean high borrowing costs for that country. For example, Argentina missed bond payments in the early 2000s, and over 10 years later interest rates on its bonds were still 12 percentage points higher than those of the U.S. Treasury.

Spending Oversight

Mistakes do happen, and improper payments do not necessarily mean fraud or a loss to the government. However, they “degrade the integrity of government programs and compromise citizens’ trust in the government.” Since all government revenue comes from its citizens, such extraneous spending does come out of paychecks. Putting an end to improper payments and conducting oversight can help reign in spending. End of year fiscal responsibility acts that would prevent federal agencies from “spending more in each of the last 2 months of a fiscal year than the agency’s average monthly spending for the previous 10 months” were introduced in both the House and the Senate in 2019. Targeting programs that lack federal mandates and having the Government Accountability Office “report overlap, duplication, and fragmentation in Federal programs” are other potential sources of oversight.

Spending Cuts and Tax Increases

A combination of spending cuts and tax increases helped reduce the U.S. government debt in the 1940s under the Truman Administration and in the 1950s under the Eisenhower Administration. Spending cuts are often key to reducing debts and deficits; as Investopedia notes, “when cash flows increase and spending continues to rise, the increased revenues make little difference to the overall debt level.”

One of the main issues with either cutting spending or increasing taxes is that “the beneficiaries of tax-payer fueled spending often balk at proposed cuts.” Americans are actively engaged citizens, and many issues Americans care about, from cancer research to solutions for homelessness, are funded by federal dollars. According to the Manhattan Institute’s Brian Riedl, “voters typically prioritize deficit reduction in theory yet oppose nearly all tax increases and spending cuts that would significantly accomplish that objective.” This often means politicians, whose tenures in office depend on the votes of their constituents, avoid taking actions that may be necessary for spending but will likely anger voters. This often means politicians, whose tenures in office depend on the votes of their constituents, avoid taking actions that may be necessary for spending but will likely anger voters.

One of the main issues with either cutting spending or increasing taxes is that “the beneficiaries of tax-payer fueled spending often balk at proposed cuts.” Americans are actively engaged citizens, and many issues Americans care about, from cancer research to solutions for homelessness, are funded by federal dollars. According to the Manhattan Institute’s Brian Riedl, “voters typically prioritize deficit reduction in theory yet oppose nearly all tax increases and spending cuts that would significantly accomplish that objective.” This often means politicians, whose tenures in office depend on the votes of their constituents, avoid taking actions that may be necessary for spending but will likely anger voters. This often means politicians, whose tenures in office depend on the votes of their constituents, avoid taking actions that may be necessary for spending but will likely anger voters.

In the U.S., the CBO predicts cutting noninterest spending or raising revenues each year starting in 2020 by 1.8% of GDP would keep the current level of debt constant in 2049. To decrease debt back to the average of the past 50 years of 42% of GDP, increased revenues and spending cuts would need to total 2.9% of GDP each year.

Another question is how exactly to go about reducing the deficit, and when to start efforts to reduce spending is an important component. Reducing deficits through spending cuts as soon as possible would “require older workers and retirees to sacrifice more but would benefit younger workers and future generations.” Waiting to make such changes in spending “would require smaller sacrifices from older people but greater ones from younger workers and future generations.”

Decreasing deficits is a long-term goal and thus requires long-term thinking. Although cuts in spending or increases in revenue would “dampen overall demand for goods and services, thus decreasing output and employment,” such a dampening is only expected to be temporary. Prices and interest rates would respond in accordance with supply and demand, and the Federal Reserve would also take monetary policy actions. The Manhattan Institute’s Brian Riedl suggests long-term adjustments such as setting a specific target so lawmakers share a goal to work towards in negotiations, and creating “laws that impose gradual reforms down the road” for future savings. For more on these economic effects, see The Policy Circle’s Economic Growth Brief.

Conclusion

Economic experts and policymakers may not all agree on how serious a problem excessive debt is, but it is clear the country is living beyond its means and is not on a fiscally responsible path. The nation’s debt, and projections of the debt, need to be brought down to a sustainable level. Understanding the primary drivers of our debt is half the battle, but amounts to little without actually taking steps to enact reforms that foster a fiscally solvent agenda. The sooner our leaders start pursuing sensible reforms to put our country on a sustainable path for the long-term, the easier they will be to implement.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Find out what your state and district are doing about budget concerns.

- Do you know the state of budget and finances in your community or state?

- What are your state’s budget policies and tax policies?

- Is there a task force or organization that addresses this, or does one need to be formed?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Who leads your state’s Office of Management and Budget?

- Who in your community is a subject matter expert? Consider financial institutions, professionals in the financial field, or teachers.

- What steps have your state’s or community’s elected and appointed officials taken?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with local hospitals, community organizations, school boards, and local businesses.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, communications@thepolicycircle.org, for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policy makers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Educate yourself – read frequently, or see what resources may be available at your community organizations, local financial institutions, or local businesses.

- Educate others – can you be a mentor through a community organization, financial institution, or with your school district?

- Visit your state’s Office of Management and Budget website to take a closer look at your state’s finances.

- See how your state ranks in terms of debt, and how it compares to other states.

- Hold your public officials accountable. Which committees oversee state finances?

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.

Thought Leaders and Additional Resources

- COVID Money Tracker

- Initially formed to advocate for the recommendations made by President Reagan’s Grace Commission, Citizens Against Government Waste continues to highlight wasteful government spending. They are perhaps best known for their annual Congressional Pig Book Summary of the most glaring and irresponsible pork-barrel projects passed by Congress. Here’s a survey that lists some government programs that CAGW thinks should be cut.

- The libertarian CATO Institute has a Downsizing the Federal Government project that provides some very specific ideas about how to get spending under control in an agency-by-agency review.

- The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget comprises a group of some of the country’s leading budget experts, including many of the past Chairmen and Directors of the Budget Committees, the Congressional Budget Office, the Office of Management and Budget, the Government Accountability Office, and the Federal Reserve Board. They are a good source of reliable information about the debt and deficit, and tend to favor tax increases as much as spending restraint.

- This Wired article has some helpful tips on the best ways for constituents to reach their members of Congress, noting that “the consensus among activists and staffers alike is phone calls are better than email, and that showing up in person to district offices or town halls is better than phone calls. But email and social media make a difference too, as long as those communications are personalized.

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.

State Briefs

Want to learn more about how states are dealing with this issue? Read our state-specific briefs below: