Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

Listen to The Civic Leader Podcast for an audio version of this brief.

Watch The Policy Circle’s Move the Needle Virtual Experience: Health Care Landscape & 2021 Forecast:

Case Study

In Marion, North Carolina, the Buchanan family decided to go without health insurance for the first time in their lives, rather than pay $1800 per month. Although their income puts them in the top fifth of households, their insurance premium was three times the price of their mortgage. In addition, their high deductible meant having and using their health coverage would cost over $30,000 annually. Instead, they now pay about $200 per month for membership in a local doctors’ practice that allows them unlimited office visits and discounts on medications and lab testing

In Phoenix, Arizona, the Bobbies and their son will remain uninsured, hoping this savings will help them pay for the special heart treatments their nine-year-old daughter needs. Their daughter qualified for Arizona’s Medicaid program, but the family was later told they made too much money to get low-cost state coverage. Before their daughter had turned three, medical costs amounted to over $1 million, and caused the Bobbies to lose their house and car. When coverage through the Affordable Care Act became available to them in 2014, the Bobbies were able to buy a policy for Sophia that costs just over $200 per month, but this did not solve their problems by any means; it is only affordable if the rest of the family remains uninsured (Bloomberg).

Why It Matters

Health care is generally defined as the organized provision of medical care. In discussion regarding how to provide health care, the conversation centers around health care systems, “the organization of people, institutions, and resources that deliver health care services to meet the health needs of target populations.”

Health insurance is a type of insurance that typically pays for medical expenses incurred by the insured by either reimbursing the insured for expenses, or paying the care provider directly. Health insurance can be privately provided by a health insurance company or publicly provided by the government. It is often included in employer benefit packages, or can be purchased individually.

The Constitution does not address health care as a specific right, but it promotes life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, of which health is a crucial part. Evidence shows that, in comparison to people without health coverage, people with health insurance have fewer out of pocket medical costs, see the doctor more often, get more preventative care, and report that they feel healthier and less depressed. It is helpful to take a look at our current health care issues — specifically the rising cost of medical insurance — to understand where we are and what can be done to improve access to health care and health insurance for all Americans.

Putting it in Context

History: The Origins of Health Insurance

According to author John Steele Gordon, modern medicine has been practiced for a very short amount of time: “More than 90 percent of the medicine being practiced today did not exist in 1950.” The ancient Greeks were the first to recognize that disease had natural, not supernatural, causes, but great innovations in medicine were still centuries away. Tools such as the stethoscope, ideas such as germ theory, and medicines such as anesthesia paved the way for great advancements in the 1800s.

The 19th century was a turning point for hospitals; originally for the poor, hospitals gradually became treatment centers as better sanitary procedures were introduced. With more use, however, came more costs, and hospitals quickly suffered financial problems. A way to finance running hospitals was through hospital insurance, a precursor to modern health insurance. Groups of hospitals quickly joined together to offer plans, and this became the model for the first health insurance company, Blue Cross, which opened in 1932.

During World War II, another health care development emerged: employer-paid health insurance, when the federal government instituted wage controls and companies began looking to provide non-cash benefits to compensate their employees. The IRS ruled employer-paid health insurance was a tax-deductible business expense, which made it attractive for employers to offer. Working Americans began to take the plans their employers provided, which sometimes meant Americans did not search for the most cost-effective plan. Additionally, subsidies for employers often destabilize the individual market.

Government became involved in health care during the 1960s, when President Johnson signed the bill that led to the introduction of Medicare and Medicaid; these programs had a structure similar to that of Blue Cross, but since the government was making the payments, health care providers were pleased because even more people could afford medical care. This also gave state governments the ability to influence policy decisions at hospitals, many of which were political rather than economic.

The highly controversial 2010 Affordable Care Act (also known as the “ACA” or “Obamacare”) resulted in even greater government involvement in the health care system. The ACA allowed millions of Americans to purchase health insurance via new government exchanges or obtain coverage through Medicaid. Through the act, the government also introduced subsidies for people with annual incomes below 400 percent of the poverty line to offset the costs of insurance premiums for plans available on the state exchanges.

All of these developments in health care came with a price tag: In 1930, Americans spent $2.8 billion on health care, approximately $23 per person and 3.5% of GDP. In 2020, that figure was $4.1 trillion —$12,530 per person and 19.7% of GDP. Adjusted for inflation, per capita medical costs in the U.S. are now over 30 times higher than they were 90 years ago. Costs for 2021 are projected to total $4.3 trillion, although government spending as a portion of overall health spending is projected to decline from its pandemic high.

See this timeline from PBS for more on the history of U.S. health care, and this video for background on how the U.S. health care system works. Note the statistics in this video are out of date, but the overview of how the system functions is accurate (10 min):

Where do Americans get insurance?

For the most part, the U.S. has a third-party payer system, meaning health insurance plans (third parties) reimburse doctors for costs of services provided to patients. There are both public and private programs available to Americans.

Public

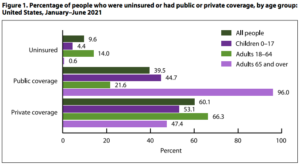

In 2021, 39.5% of Americans had public healthcare coverage. Adults age 65 and over were the most likely to have public coverage (96%). The four major public healthcare programs are Medicaid, Medicare, the military health system, and the health system offered by the Department of Veterans Affairs. These four programs provide healthcare for seniors, low-income Americans, members of the military, and veterans, respectively.

Medicaid includes coverage by Medicaid, Medical Assistance, and Children’s Health Insurance Plan (CHIP). Medicaid is a state-run program, jointly financed by state and federal funds, that serves about 58 million lower-income U.S. residents. To receive federal funding, state Medicaid programs must cover children in families below 138% of the federal poverty line, pregnant women and children in families below 138% of the federal poverty line, as well as seniors and people with disabilities who receive SSI benefits through Social Security. About ten million low-income seniors and people with disabilities qualify for both Medicare and Medicaid. CHIP is similar to Medicaid in structure but is specifically for children.

Medicare includes coverage by Medicare and Medicare Advantage and is the largest federal health care program that serves almost 60 million elderly and disabled people in the U.S.. There are four parts of Medicare:

- Part A (Hospital) pays for your care in a hospital, skilled nursing facility, nursing home (as long as it’s not just for custodial care), hospice and certain types of home health services.

- Part B (Medical) covers medically necessary services or supplies needed to diagnose and treat a medical condition. It also covers preventive services for illnesses such as the flu, including inpatient and outpatient physician services and some limited outpatient prescription drugs.

- Part C (Medicare Advantage), also known as MA plans, is sold by private companies. MA plans come in two varieties – HMO plans and PPO plans – and take the place of Medicare Part A, Part B and, often, Part D coverage. Many offer extras such as vision, dental, hearing aids and wellness services.

- Part D (Prescription Drugs) provides prescription drugs from a list (called a formulary). Each Medicare prescription drug plan has its own list. Most plans place drugs into different “tiers,” with each tier having a different cost.

TRICARE through the Department of Defense is the government’s health insurance coverage for 9 million members of the military and their families. The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) provides health insurance and other benefits to 3 million American veterans. Combined, these two healthcare programs cost $136 billion dollars in 2020, only 3.5% of overall healthcare spending in America.

Private

In 2021, 60% of Americans had some form of private insurance, mostly through their employer. Adults age 18-164were the most likely to have private coverage (66.3%). For individuals whose employers do not offer insurance or who are self-employed, there is also the option to purchase private insurance. Another 9.6% of Americans were uninsured.

Employer-paid insurance includes coverage through a current or former employer or union, as a policyholder or dependent. In 1943 the IRS ruled that employees do not have to pay taxes on group health insurance premiums paid on their behalf by their corporate employers. This tax exclusion meant that the value of the health care benefit to the employee was greater than if a company offered the employee the same amount of cash, which would have been taxable. Thus, more and more employers began offering health insurance plans as part of attractive compensation packages for their employees. Each year, the single largest tax exemption, worth an estimated $352 billion, is the IRS’s decision to exempt employer-provided healthcare premiums from federal payroll and income taxes. This tax exemption is worth more than the annual cost of implementing the Affordable Care Act.

Kite and Key Media further explains “America’s Accidental Healthcare System” (2 min):

The Role of Government

Federal and state government is currently deeply involved in health care. Its spending, regulations, and its tax code all play a large role in structuring the current market. Much of government involvement in the health care system comes from the Department of Health & Human Services (HSS), which includes agencies such as the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

The following Congressional Committees have jurisdiction over health care matters:

Senate Committees

- Committee on Finance

- Committee on Health, Education, Labor & Pensions (HELP)

- Committee on Appropriations

House Committees

- Committee on Ways and Means

- Committee on Energy and Commerce

- Committee on Appropriations

- Committee on the Budget

At the state level in particular, states provide health insurance coverage for their respective state employees. In terms of the ACA marketplaces, 21 states have at least some control over their exchanges with either state-based, federally-supported, or partnership exchanges.

Of the $4.1 trillion spent on health care in 2020, the U.S. government contributed half, mainly through Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and military and veteran health. The federal government contributed 36% of spending while state and local governments accounted for 14%. Medicare cost about $830 billion and Medicaid and CHIP cost about $670 billion in 2020.

Federal expenditures on healthcare increased by 36% between 2019 and 2020, almost entirely due to increased spending in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) indicates Medicare paid $16.6 billion, an average of $24,033 per beneficiary, for almost 700,000 COVID-19 hospitalizations from January 2020 to March 2021.

Proponents of single-payer government healthcare system argue that the government should guarantee and subsidize universal coverage, consolidate providers into large organizations, and have experts manage federal spending in a way that drives efficiency throughout the health care system. Calls for “Medicare for All,” which would involve complete or majority control of the health care system by the government, have been making headlines in recent years. See more on Medicare for All below.

Free-market advocates favor increasing competition to make insurance more affordable so that people will voluntarily buy it and introduce more market-based approach to consumption. They believe the government should take a more modest role and allow a functioning market to emerge. This creates a closer relationship between the consumption and payment of health services, and empowers consumers within that market.

For more on the history of the role of government in the health care system, see this CMS report.

Current Challenges and Areas for Reform

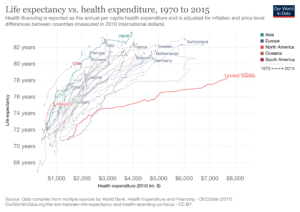

A frequently cited statistic is that the U.S. spends significantly more on health care than other developed countries but does not report much better health outcomes in areas such as infant mortality and life expectancy. These statistics, however, need to be understood in context to truly grasp the challenges the U.S. health care system faces and how to best fix them. For example, as Sally Pipes of the Pacific Research Institute points out, different countries have different definitions of infant mortality, and “America’s seemingly poor performance is largely attributable to lifestyle and social factors – not the quality of the institutions that make up its health care system.”

Author John Steele Gordon explains that the U.S. health care system was originally designed around temporary treatment in hospitals. Today, however, the “serious, long-term, expensive-to-control illness” is the new normal. The design of the health care system has not changed to meet this new challenge of managing chronic disease, which leaves room for improvement: current barriers to health services in the U.S. include high costs and lack of coverage, and uneven distribution of services.

Cost

In 2020, the U.S. spent almost 20% of its GDP on health care, mainly because of pandemic-related health expenditures. Health spending as a portion of GDP is not predicted to decline to pre-pandemic levels, and instead could surpass 20% of GDP by 2030 if health spending continues to grow more quickly than the overall economy.

Costs also vary widely within the U.S.: an MRI of the lower back costs about $140 at an imaging center in Louisiana but costs over $7,600 at a center in California. A Wall Street Journal analysis of private insurance found prices for COVID-19-related hospitalizations within the same hospital ranged from $55,000 to $94,000, and that prices did not depend on the care provided to the patients but rather “reflect the leverage than an insurer has to wrangle discounts, as well as the hospital’s market power to drive up its rates.” Experts also speculate price differences result from differences in demand for health care services or supply of providers, provider and insurer market power, and even health characteristics of the populations.

You can compare health care prices and use levels across the country with Health Cost Institute’s interactive Healthy Marketplace Index.

Author John Steele Gordon also recommends reforming the present system to be more transparent by requiring providers to make their prices public. “Once prices are known and can be compared, competition…will immediately drive prices towards the low end,” he says. “Posting prices will also force hospitals to become more efficient and innovative, in order to stay competitive.” In November 2019, then-President Trump announced a rule that would require hospitals to disclose prices for services and treatments such as x-rays, outpatient visits, and lab tests, arguing it would help patients “obtain an estimate and understanding of the individual’s out-of-pocket expenses and effectively shop for items and services.”

Some medical organizations including the Federation of American Hospitals and the American Hospital Association warn that revealing costs could cause confusion, and “undercut the way insurers pay for hospital services” because there are large differences in how services are reimbursed by Medicare and private insurance. The American Hospital Association sued to stop the initiative, but a federal judge ruled in favor of the policy, which took effect January 1, 2021. Federally mandated price disclosures have revealed the absurd variation in price for a single procedure. At one California hospital, the cost of a C-section ranged from $6,241 to $60,584, based on what various insurance plans negotiated to pay the hospital.

In July 2021, the Biden administration proposed higher penalties for large hospitals that don’t make their prices public. A Wall Street Journal found that hundreds of hospitals use special coding embedded in hospital price webpages to prevent them from being displayed in search engine results. Price transparency startup Turquoise Health reported no usable pricing data from roughly one-third of almost 5,000 acute care, children’s or rural primary care hospitals.

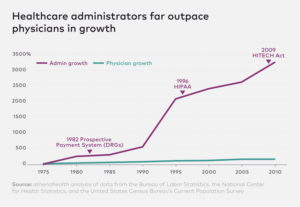

Administrative Costs

Several layers of separation exist between consumers of healthcare and insurance companies. Each insurance company sets its own price for thousands of different drugs and medical procedures. The interaction between thousands of different employers, health insurance companies, doctors and hospitals, and drug companies requires a massive bureaucracy to process medical billing and negotiate prices and premiums. This is why the growth of administrative positions has far outpaced the increase in the number of doctors over recent decades. Administrative costs make up a higher proportion of healthcare spending in the United States than in other developed countries.

Prescription Drugs

In 2020, the government, consumers, and insurers spent $348.8 billion on prescription drugs, according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The Rand Corporation estimates annual spending on prescription drugs to be closer to $460 billion.

Insurance plans handle negotiations for drug pricing in the U.S., but this does little to lower costs. Some of these drugs, like intravenous solutions, are used by hospitals and have been identified by the FDA to be in short supply, which greatly affects prices. Between 2008 and 2016, costs for generic oral prescription drugs rose almost 10% annually, and injectable drug prices rose over 15% annually.

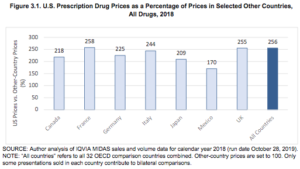

In international comparisons, U.S. prices for drugs are for the most part considerably higher than other countries. U.S. drug prices in 2018 were 256% of prices in 32 OECD comparison countries. U.S. prices were slightly lower than international averages for unbranded generic drugs, but were substantially higher for brand-name drugs. Brand-name drugs account for 11% of U.S. prescription drug volume but 82% of U.S. prescription drug spending.

Congress has tried to address drug pricing, specifically in Medicare and Medicaid. It is important to remember that while the U.S.’s high drug pricing is an issue that garners a lot of attention, it’s also a contributing factor to U.S. scientific innovation. One study found about $2.5 billion in revenue is required to “support the invention of one new chemical entity.” Additionally, the U.S. has more clinical trials than anywhere else in the world, accounting for almost half of the world’s total.

The Wall Street Journal explains how drug prices in the U.S. work:

The FDA and “Right to Try” Laws

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) undergoes a lengthy approval process to show that newly developed drugs are safe and effective at their intended purpose before they reach consumers. This process can have benefits and drawbacks: the process prevents dangerous or ineffective drugs from harming American consumers, but also means that patients can die waiting for life-saving drugs to work their way through the approval process.

To prevent this, the federal government and many states like Arizona have passed “right to try laws” that allow people with terminal illnesses to use experimental treatments that have passed the first phase of clinical trials, but not full FDA approval.

Hospitals

As of early 2022, there are 6,093 hospitals across the United States. Around 200 of these hospitals are directly run by federal agencies such as the Military Health System, Department of Veterans Affairs, and Indian Health Service to serve specific groups of patients like Americans serving in the military, veterans, and Native Americans.

The vast majority of hospitals in the United States are part of America’s network of just over 5,000 community hospitals, which are non-federally funded and serve the general public in surrounding communities. One-fifth of these hospitals are funded by state and local governments. In 2019, state and local governments spent $322 billion on public hospitals.

Around 60% of America’s hospitals are organized as non-profit organizations, which means they are exempt from federal and state taxes in exchange for providing charitable benefits to surrounding communities. However, just under half of nonprofit hospitals make a profit each year, and seven of the ten most profitable hospitals in America are officially tax-free, nonprofit entities.

Rural Hospitals

Even before the pandemic, America’s rural hospitals system was in a state of financial crisis: between 2013 and February 2020, 100 hospitals closed across rural America. Before the pandemic started, 800 rural hospitals, 40% of the hospitals serving rural communities across America, were at risk of closing. These hospital closures would affect at least 20 million Americans’ access to healthcare.

Hospital closures have left many rural communities more than an hour’s drive away from the nearest emergency room, and a limited number of ambulances are spread thin over larger and larger areas. This travel time can mean the difference between life and death in emergency situations: one study of hospital closures in rural California identified a 5.9% increase in mortality rates in the affected communities.

Hospital closures in rural areas have a disproportionate impact on low-income and senior Americans. The patient populations that rural hospitals serve are more likely to receive Medicare or Medicaid, or be uninsured. Because these government health insurance programs generally reimburse hospitals less than private insurance, medical services are provided at a lower profit margin, or even a financial loss.

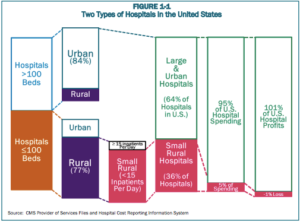

As the image above shows, hospitals in rural areas tend to be much smaller and face inherent economic challenges as a result. There are 3,200 counties in the United States, and the majority of them have fewer than 26,000 residents. The typical rural hospital in America takes in no more than 15 new patients per day, and has fewer than100 beds. This makes rural hospitals very unprofitable because the fixed overhead costs of facilities, personnel, and equipment can only be covered by revenue from a very small number of patients.

Rural hospitals across America continued to close throughout the Covid-19 pandemic. A study from the University of North Carolina found that 19 rural hospitals closed in 2020, followed by two more closures in 2021 and one as of early 2022. One-time, emergency funding granted through the 2020 CARES Act provides a temporary band-aid, but a more sustainable solution to this problem will probably require changes to Medicare and Medicaid reimbursed in policy proposals like the Rural Hospital Support Act.

Certificate of Need Laws

If a given state or region is facing a shortage of hospital beds and medical facilities that is driving up prices and increasing wait times, can investors or nonprofit philanthropists just open a new hospital to address this need? In 35 different states and Washington DC, Certificate of Need Laws mean that building new facilities or adding more hospital beds and equipment to existing facilities requires proving to state regulatory boards that a shortage of these services exist.

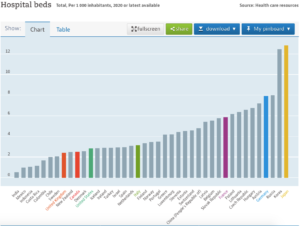

These laws were originally passed as part of federal effort to centrally plan the construction of new healthcare facilities, with the reasoning that a greater supply of medical facilities and equipment would somehow increase the price of medical treatment. A state regulatory board in Virginia denied a hospital’s request to build neonatal intensive care units because another facility nearby protested about unwanted competition, and regulators in Michigan restricted access to a promising new cancer treatment on similar grounds. These regulations contributed to a scarcity of hospital beds in the United States relative to America’s population.

Doctors and Patients

According to Seema Verma, former administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, the fee-for-service method creates “perverse incentives to offer more care.”

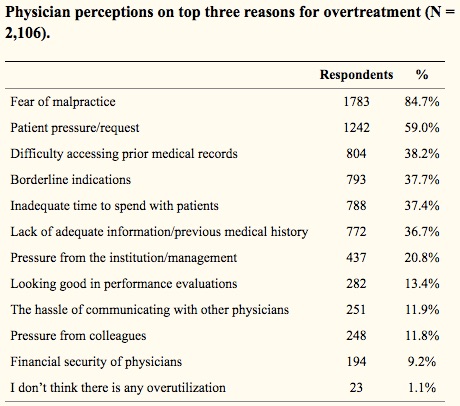

Most experts agree that patients in the U.S. are frequently overtreated, although one Johns Hopkins’s study also found overtreatment was not usually due to high incomes for doctors and hospitals; the two most common reasons cited for overtreatment were patient demand and fear of malpractice. Medical practices and treatments pursued to avoid malpractice litigation are called defensive medicine, and can cost somewhere in the realm of $50 billion annually. Addressing medical malpractice reform with the costs of defensive medicine in mind may help lower excess health care spending.

The Affordable Care Act

The 2010 Affordable Care Act was introduced as a solution to many of the pressing problems of cost and access. The objective of the ACA was to offer access to health insurance to the nearly 48 million people in 2010 unable to get health insurance — or good health insurance — through employers. The following are a few main features of the law:

- Millions could purchase health insurance via new government exchanges or obtain coverage through Medicaid, the government-run health-care program intended for the poor, which many states dramatically expanded via incentives in the ACA.

- For those who qualify, the government provides subsidies to offset the costs of insurance premiums for plans available on the exchanges.

- Insurance companies are required to offer health insurance to people with pre-existing conditions on the same terms as to others.

- All would be required to purchase health insurance; those who did not would have to pay a fine (effective 2019, this tax was eliminated when Congress passed the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.)

- A new tax on expensive employer-provided policies was instituted to control costs.

The ACA got off to a rocky start, but has since extended coverage to almost 20 million people, meaning more Americans have access to health insurance.

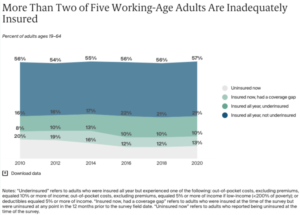

Although uninsured rates are still at all-time lows, the number of uninsured Americans began to rise starting in 2017, growing from 26.7 million in 2016 to 28.9 million in 2019. An estimated 30 million Americans were uninsured in 2020. This was due to declines in Medicaid coverage as rising wages left fewer people eligible for Medicaid, and due to the fact that more people are foregoing insurance since the individual mandate tax was reduced to zero. What’s more, the ACA is just not working for many Americans as the cost of health care continues to rise faster than Americans’ incomes: “the cost for many people to buy a health plan – if they don’t get it from a job or the government – is higher than ever.”

*(As millions have lost their jobs and potentially their health insurance due to the coronavirus pandemic’s effect on the economy, the number of uninsured Americans has likely increased further).

More people than ever are underinsured thanks to high out-of-pocket expenses and deductibles. An estimated 45 million people were underinsured in 2020, up from 29 million in 2010. Compared to insured adults with adequate coverage, underinsured adults are more than twice as likely to not fill a prescription, to skip a recommended test, treatment, or follow-up appointment, and have medical debt.

While opponents of the ACA have not reached a consensus on a replacement plan, several policy prescriptions have attracted widespread support:

- The ability to buy health insurance across state lines to create more market competition and choice in policies;

- Secure renewal of health insurance that is guaranteed so people who have health insurance can keep it and not see premiums soar if they get sick;

- Cost transparency so people can know the price of their insurance and medical services

For more on the ACA, see The Policy Circle’s Affordable Care Act Deep Dive.

Medicare for All

Medicare for All is the plan for universal health care that expands Medicare coverage to everyone and would be funded through taxes. It is referred to as the single-payer health care system. In a single-payer health care system, everyone is covered by one government-run health plan that pays for all services. In some cases, as in the bill presented by Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) private insurance would be outlawed. Other ideas involve giving more people access to government-funded health care by lowering the eligibility age for Medicare or offering a public option through Medicare or Medicaid buy-in. In these cases, private insurance would remain, as would Medicare Advantage, through which the government pays private companies to run Medicare plans. In all cases, the government insurance plan competes with private-insurance.

Costs

The most widely-cited Medicare for All plan is Senator Sanders’s bill. Mercatus and the Urban Institute both estimate the costs of this plan over the next 10 years would add about $30-$34 trillion to the federal budget – this would be on top of the estimated $17 trillion in federal government spending on health care over the next decade, projected by the Congressional Budget Office. Federal government spending on health care makes up about 28% of all health care spending, amounting to just over $1 trillion annually.

Proponents of single-payer government healthcare programs point to administrative cost savings as one of Medicare for All’s advantages, on the reasoning that one government agency handling medical billing would streamline the process of medical billing because providers like doctors and hospitals would only be processing most medical billing through a single government agency rather than dozens of different health insurance companies.

Some doctors voice opposition to single-payer systems on the basis of payment; at present, public programs reimburse doctors at a rate much lower than in the private market. Based on this trend, doctors would be paid less, and the autonomy of their medical practices would be impacted.

Runaway costs are also frequently a problem in health care, as Sally Pipes of the Pacific Research Institute notes in her book, False Premise, False Promise: The Disastrous Reality of Medicare for All (p. 32). When Medicare added dialysis coverage in 1972, the actual cost ended up being more than twice the estimated amount of $209 million, and that was only for one small piece of coverage. Additionally, Medicare made over $25 billion worth of improper payments annually since 2019.

This means the single-payer system may cost much more than the projections estimate, which means more taxes will be needed to fund the system. The Rand Corporation estimates a single payer plan in New York would require about $140 billion in new state tax revenue, approximately double what New York currently collects in taxes.

The Washington Post Fact Checker takes a closer look at the costs of a single-payer system:

Quality of Care

In a health care system, there are limited numbers of doctors, hospitals, services, and amenities, from treatments to testing to hospital beds, but there is a potentially unlimited demand from patients. This will inevitably lead to longer wait times. In her analysis of the UK’s and Canada’s single-payer systems, Sally Pipes, a Canadian, found the quality of care available in these countries is very different than in the US (p. 64). For example, average wait times in Canada for a CT scan are 4-5 weeks, mainly because there are fewer than 20 machines for every million people. For an MRI, of which there are about 10 per million people, waiting times are 10-11 weeks. Between hospitals and outpatient care facilities, the U.S. has 44 CT scanners per million people and almost 40 MRI machines per million people.

In the Fall of 2019, only 74.5% of patients seeking care in Accident and Emergency (A&E) units in the UK were seen within four hours, marking the lowest percentage since the target of 95% was set in 2004. In the U.S., average emergency department waiting time is an hour and a half. For non-emergency treatment, as of June 2019, over 4 million people across the UK were waiting due to a lack of available hospital beds and available staff. Meanwhile, the UK’s National Health System doctors and nurses work an average of 3-4 hours of unpaid overtime per week.

This doesn’t even begin to touch on the procedures and prescription drugs that are not offered by other countries’ health systems. For example, in countries such as Canada, Germany, and Japan, governments engage in negotiations with drug manufacturers to keep prices low, but Sally Pipes notes this also means these health systems choose to limit the drugs they offer because they are too expensive to begin with (p. 107). In the U.S., consumers spend about three times as much on drugs as European consumers do, but much of that spending is because American patients have more access to newer and more expensive treatment options. Additionally, that spending contributes to innovation and research that leads to widespread development of procedures and prescription drugs, and explains the U.S.’s low mortality rates for breast, colorectal, and cervical cancers in comparison to other countries.

While average prices for medical procedures, hospital costs per day, and prescription drugs are higher in the U.S. than elsewhere, patients in the U.S. actually have greater, easier, and faster access to these treatment options and services. Sally Pipes outlines how these services can be improved through other means. For example, short-term health insurance plans and Health Savings Accounts are options that could allow more people to get coverage that fits their specific health and budgetary needs. On the supply side, expanding licensing reciprocity so professionals can practice around the country without needing to seek state-specific license can ensure there is no shortage of physicians in the U.S.

Employer-based and Private Insurance

The tax exclusion that gave employers the incentive to offer employees health insurance has created a number of problems over the past 60 years. According to health care policy expert Tom Miller at the American Enterprise Institute, the tax exclusion “has been criticized for raising – and hiding – the overall costs of health insurance and health care.” It also limits choices for individuals, and “dispenses its rewards disproportionately to higher-income workers in larger companies with better-paying jobs.”

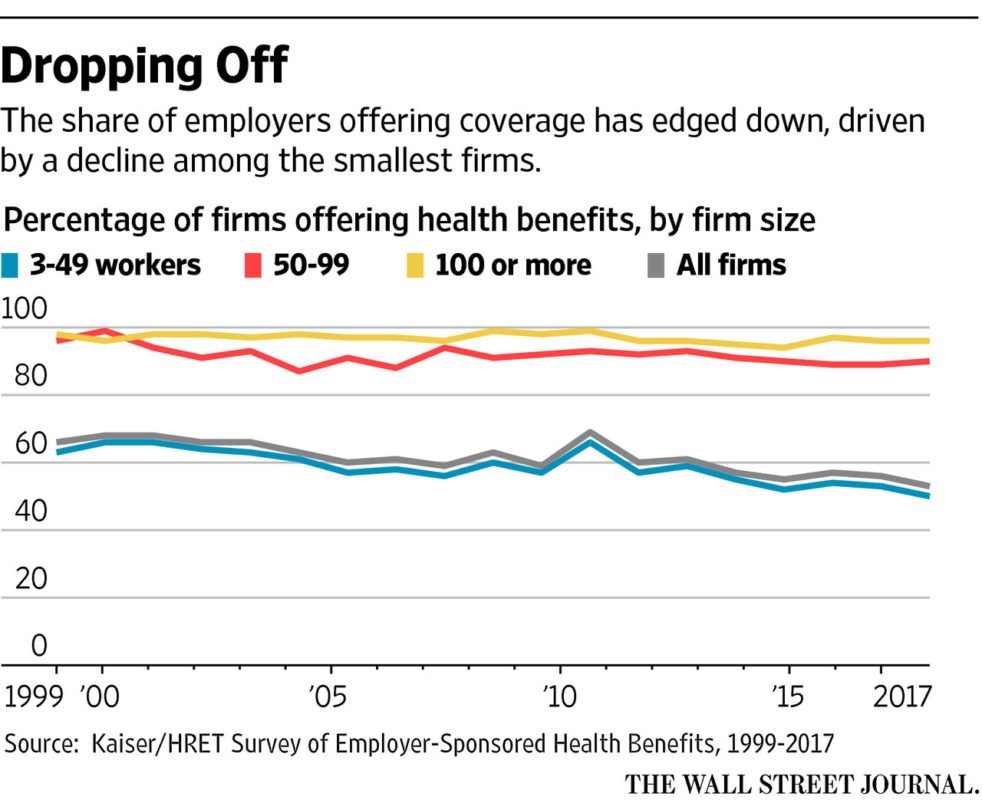

This is mainly because large companies have the most leverage when negotiating with insurance companies. Whereas only 40% of small companies with fewer than 25 employees offer health insurance, 97% of companies with over 100 employees offer coverage. The average premium for family coverage has increased 22% since 2016 and 47% since 2011. In 2021, the average total cost of employer-provided health coverage rose to over $22,221 for a family plan (a 4% increase from 2020) and to $7,739 for individual plans (a 4% increase from 2020). On average, employers bore 71% of the costs. Individuals who are self-employed, unemployed, or not offered insurance by an employer have additional difficulties facing rising prices, steep premiums, and meager benefits.

You can look at hospital price comparisons with the Employer Hospital Price Transparency Project, from the Employers’ Forum of Indiana and the Rand Corporation. The project gives employers access to information on hospital prices, from which many employers have seen unexplained and unsustainable health care cost increases over the past few years. For example, one of the studies found employers in Indiana were paying hospitals anywhere from two times to over three times the amount that Medicare was paying. For all medical services, Medicare rates average about 40% lower than private insurance rates, well below the costs of providing these services.

According to Gloria Sachdev of the Employer’s Forum, health plan contracts frequently include clauses that prohibit parties within the network from disclosing what the prices are, which prevents employers from being able to shop for health care for their employees. To find the best quality for the best price, one option is to address these clauses so employers can hold hospital systems and health plans accountable for price negotiations.

Another difficulty is that health insurance is regulated differently by each state. This patchwork regulation dramatically limits competition in the insurance market, causing high prices. Employers and individuals alike must purchase plans that comply with state mandates–-creating monopolies of one or two insurance companies in many states. For those who suffer from pre-existing health conditions that are serious and costly, the individual market is rarely an affordable option.

Another option is to give states a more prominent role in reforming their health insurance markets since states have a better understanding of local needs and are having trouble offering their own plans given current mandates. Idaho’s Blue Cross insurer, for example, tried to implement a plan that would help the state financially but would charge higher premiums for sick people or people with preexisting conditions. Federal officials struck the plan down but “encouraged Idaho to explore offering similar policies as short-term plans…” The problem with short term plans is that, although they tend to be less-expensive options, they lack the consumer protections that come with ACA plans.

State budgets have been in trouble for at least a decade due to health care expenditures like Medicaid and retiree health care benefits. States pay for a portion of health care bills for retired public workers, promising hundreds of billions of dollars in retiree health benefits that have resulted in a nation-wide $600 billion dollar gap. This has prompted a number of states to start “testing how far they can reduce health benefits…as a way of coping with mounting liabilities and balancing budgets.” For example, In 2017, Kansas began charging retirees the full cost of health coverage in 2017. After this, 75% of former beneficiaries dropped out, and Kansas saw its health care liability fall from over $6 million to just over $500,000.

The Role of Technology

Telehealth is an area for opportunity that could help improve health care delivery and reduce costs, which has been highlighted during the coronavirus pandemic. According to the Health Resources Services Administration, “telehealth” is defined as “the use of electronic information and telecommunications technologies to support long-distance clinical health care, patient and professional health-related education, public health and health administration. Technologies include videoconferencing, the internet, store-and-forward imaging, streaming media, and terrestrial and wireless communications.”

Telehealth includes clinical (e.g., a virtual exam) and non-clinical applications (e.g. training on how to use equipment or holding administrative meetings). Seema Verma has noted key ways that telehealth “is changing the very face of health care. Telehealth innovations could help usher in a new world of health care that is embraced by both patients and providers, that identifies new avenues of care delivery, and that improves the value of care by increasing its quality while lowering its cost.” Telehealth can be a long-term solution that allows patients to more quickly and easily access the services of specialists without the imposition of travel.

For example, Amazon’s Alexa “can track blood glucose levels, describe symptoms, access post-surgical care instructions, monitor home prescription deliveries and make same-day appointments at the nearest urgent care center.” The Apple Heart Study, a combined effort between Apple and Stanford University, uses data from Apple watches to improve technology detecting irregular heart conditions. Developments in telehealth could also reduce the burden on doctors, nurses, and medical practitioners, who often complain that entering medical information into electronic health records is currently time-consuming and takes away from interactions with patients.

Another example of digitization in practice is the Australian health system’s remote care coordination for Type 2 diabetes patients, which saw a drop in patients’ blood glucose levels by a full percentage point when managed remotely compared to only seeing a traditional doctor. Additionally, the annual cost of care per individual dropped by $900. Digital and pharmaceutical technologies “can move most chronic care from centralized hospitals, surgery centers and clinics into patients’ homes,” turning health care from a “high-cost destination” to a “low-cost delivery system” focused on value and empowering patients.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, many regulations that limited the impact of telehealth were repealed for emergency reasons, but patients and regulators are questioning whether the rules made sense in the first place. Before the pandemic, Medicare rules stated that seniors could only use telehealth services if they lived in an area that the Department of Health and Human services officially declared to have a shortage of healthcare professionals. About 40% of Medicare recipients’ doctors appointments between April and July 2020 were done virtually, and the Telehealth Modernization Act could enable 61 million seniors who receive Medicare to continue consulting with medical professionals without having to leave their homes.

Even if Medicare rules change, state medical licensing rules are a major barrier to a doctors’ ability to conduct telehealth appointments. If a patient travels across state lines to an in-person appointment with an expert doctor who specializes in their condition, the doctor can’t conduct virtual follow-ups or prescribe medication without obtaining a medical license in the patient’s home state. In summer 2021, Arizona made emergency telehealth measures created during the pandemic permanent by allowing doctors licensed in other states to conduct telehealth appointments with patients in Arizona and requiring insurance companies to cover telehealth services at the same rate as equivalent in-person appointments.

Other states like Montana and Missouri adopted similar pandemic measures that addressed a shortage of doctors by allowing licensed medical professionals in other states to treat their residents. Federal legislation can also promote reciprocal recognition of medical licensing through the federal government’s mandate to regulate and promote interstate commerce. You can find out what telehealth services your state allows in this report.

You can read more about telehealth in The Policy Circle’s Digital Landscape Brief.

Conclusion

Health care reform is one of the most contested issues in U.S. politics, as all Americans are facing high costs and limited access. Current laws and mandates do not work for everyone. Even before the coronavirus pandemic, reform was necessary and inevitable. It is important for lawmakers, businesses and employers, and individual citizens to be aware of the current state of health care and the reforms under consideration to come up with the best solution for Americans.

What You Can Do/Ways to Get Involved

Many options for health care reform are being considered. It is essential that American citizens remain aware of the options so they can contribute to dialogue and make their voices heard. Here are some resources to explore:

- Research your elected representatives’ positions on health care law and his or her vision for how to tackle the health care challenges facing Americans at large and your community specifically.

- Start by searching on your state or municipality’s website for your local Department of Health using keywords such as health care or department of health.

- You can also search for health care in your state on Ballotpedia.

- At the national level, GovTrack tracks bills in the House and Senate.

- Make your voice heard

More resources:

Department of Health and Human Services

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

USA.Spending.gov

Why Are the Prices so Damn High?

Notable Organizations:

- Network for Regional Healthcare Improvement is an organization representing other state and regional affiliated partners working to collaborate health care improvement across regions.

- The Kaiser Family Foundation is a nonprofit organization that focuses on national health issues.

- The RAND Corporation is a nonpartisan, nonprofit organization that does research and analysis on areas including security, health, education, sustainability.

- The Galen Institute is a non-profit public policy research organization that focuses on policies to create a patient-centered health sector that offers greater freedom and more affordable health care choices.

More:

The Galen Institute President Grace-Marie Turner testified before Congress about the path to universal coverage in the U.S. Read the full transcript here.

The Pacific Research Institute’s CEO and health care expert Sally Pipes discussed the future of health care and how single payer systems actually function. Listen to the podcast here.

Education and Health care face similar debates, centered around what role the government and individuals should each play in making decisions and controlling resources in these service industries. First, both face “rising prices, consumer criticism,” and questions of quality. Additionally, both are subsidized by the government, who is not the consumer, which means consumers have little power over producers and producers have little incentives to cut costs.

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.

Deep Dives

Want to dive deeper on Health Care? Consider exploring the following:

State Briefs

Want to learn more about how states are dealing with this issue? Read our state-specific briefs below: