Disparities in health and health care across the United States reveal weaknesses in the country's health systems. Understanding what these disparities are, how they originate, and their effects on health outcomes and the health care system can help determine strategies and policies that benefit the health of individuals, their communities, and the United States as a whole.

Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) defines health disparities as, “‘differences that exist among specific population groups in the United States in the attainment of full health potential that can be measured by differences in incidence, prevalence, mortality, burden of disease, and other adverse health conditions’.” These are linked to social, economic, and environmental differences ranging from concentrated poverty and insufficient access to healthy food to limited transportation or exercise options and unsafe housing. The “conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age,” referred to as the social determinants of health, can have lasting impacts on individual and community health.

The presence of these disparities in the U.S. is illustrated simply by U.S. life expectancy. Life expectancy is a statistical estimate of the average lifespan of people in a given country. For instance, America’s life expectancy in 2002 was 77.1 years. This means that public health officials collected data on the mortality rate of Americans from various causes of death in the year 2002, then calculated how long the average person born in 2002 would live if the mortality rate remained the same over their entire lifetime.

From 2014 to 2018, for the first time in a century, American life expectancy declined for five years in a row. The pandemic only made this situation worse, with further decreases in life expectancy due to Covid-19 in 2020 and 2021: America’s life expectancy decreased from 78.9 years in 2019 to 76.2 years in 2021.

That’s at the national level; when broken down, life expectancy looks very different. For example, Americans born in Hawaii, California, New York, Minnesota, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New Jersey, Washington, and Colorado can expect to live longer than 80 years. Meanwhile, those born in West Virginia, Mississippi, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Tennessee, Kentucky, and Alabama all live less than 76 years on average.

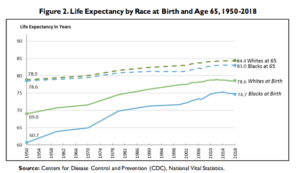

Differences in life expectancy also correlate to race:

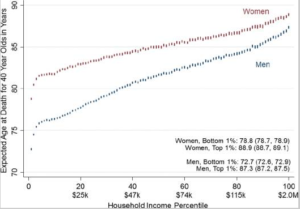

And by socioeconomic status (which measures income, education, and occupation):

Explore more data with the CDC’s National Vital Statistics Report.

Why it Matters

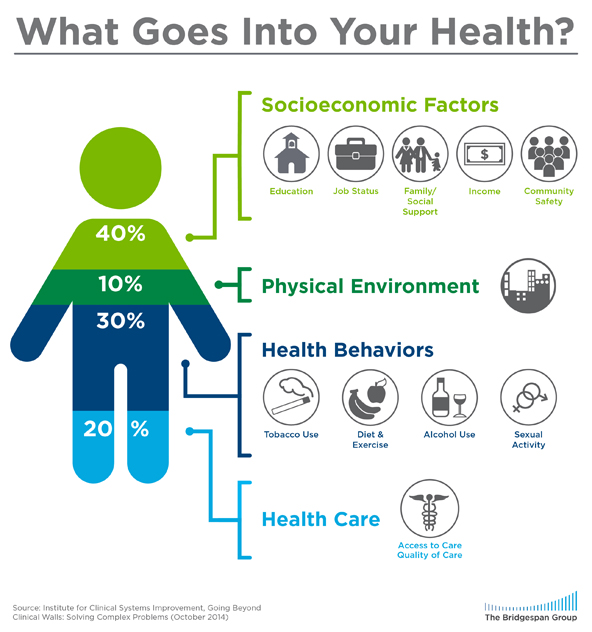

The National Academy of Medicine estimates medical care, the care you receive directly from a medical practitioner, accounts for only about 10-20% of health outcomes. Health outcomes are measures of well-being such as quality of life and chronic disease burden. This means that at least 80% of health outcomes may depend on social, economic, and environmental factors and their effects. If such a large fraction of health is left unaddressed, says the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), it “may increase the risk of developing chronic conditions, reduce an individual’s ability to manage these conditions, increase health care costs, and lead to avoidable health care utilization.”

Greater shares of the population experiencing poorer health outcomes can significantly put the health of all Americans at risk by increasing public spending and health care costs. These expenditures can limit overall gains in quality of care. By one estimate from the Kaiser Family Foundation, “disparities amount to approximately $93 billion in excess medical care costs and $42 billion in lost productivity per year as well as economic losses due to premature deaths.” As calls to reform the health care system grow louder, it will be impossible to do so without an understanding of all the factors that contribute to health.

Putting it in Context

History

In 1983, HHS produced a report on the health of the U.S. that indicated “major disparities existed in ‘the burden of death and illness experienced by blacks and other minority Americans as compared with the nation’s population as a whole’.” This prompted a government task force to conduct a study of minority health problems, which produced the “Report of the Secretary’s Task Force on Black and Minority Health” in 1985, commonly known as the Heckler Report after HHS Secretary Margaret Heckler. The report “offered a stark and compelling account of the prevalence of health disparities among racial and ethnic minorities in the United States.” This was the first comprehensive government study of minority health status ever. One year later, in 1986, the Office of Minority Health was established under HHS and major health care organizations including Robert Wood Johnson and The Commonwealth Foundation began addressing health disparities.

By the Numbers

Access to and availability of health care services, access to nutritious foods, access to education and employment opportunities, and geographic location all impact rates of chronic disease and overall well-being, and exist across dimensions such as “gender, sexual orientation, age, disability status, socioeconomic status, and geographic location.” Taking all these factors into consideration as it relates to healthcare is crucial for developing policy solutions for all Americans.

Access

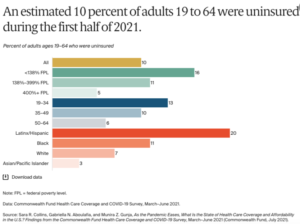

When people lack access to health care services, they delay care and preventative services or their health needs go unmet, which can result in increased risk of chronic disease and related complications. People may delay or lack access to care based on their physical location if they live far from health services, or based on cost, if they lack health insurance, for example. The Commonwealth Fund breaks down the uninsured rates by race and ethnicity, based a 2021 survey:

Education and Employment

In the U.S., the most commonly reported types of disabilities are related to mobility and cognition. People with these disabilities have”an increased likelihood of not having a high school education, less likelihood of employment,” and “an increased likelihood of having an annual income less than $15,000.” Studies have shown that education- and income-level disparities are associated with chronic health conditions as well as poor mental health stemming from “navigating everyday circumstances, anxiety about insecure and unpredictable living conditions, and perceived lack of control.”

Maternal Health

According to the CDC’s 10 year study on pregnancy-related mortality, non-Hispanic black and non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native women over 30 experience pregnancy-related deaths per 100,000 births at a rate four to five times higher than white women. In particular, chronic conditions such as hypertensive disorders contributed to more pregnancy-related deaths among non-Hispanic black and non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native women than white women. These differences hold regardless of levels of education and geographic location.

Food Insecurity

Households that do not always have access to enough food are referred to as food insecure. In 2020, the Department of Agriculture reported rates of food insecurity were higher than the national average (10.5%) for Hispanic households (17.2%), Black households (21.7%), and households with children headed by a single woman (27.7%) and single men (16.3%). Food insecure households often rely on foods that are less expensive, more convenient, and less nutritious; consumption of these less nutritious foods have been linked to increases in chronic disease from high blood pressures to diabetes to cancer.

Geography

Between states, life expectancy can vary by up to 7 years for males and 6.7 years for females. Even in smaller geographic areas, there can be large disparities; data from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation illustrates life expectancy between neighborhoods in Kansas City has differed by 14 years, and by 25 years in New Orleans. Some determining factors of neighborhood disparities include food insecurity, violence, pollution, and the availability of resources such as hospitals, transportation options, and green spaces.

For more data on your state, see your state’s profile from America’s health Ranking (start page 57). At the local level, use data from PLACES, a collaboration between the CDC and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation that provides health data for small areas across the country.

The Role of Government

Federal Agencies

According to the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion’s Healthy People Framework, “Health and well-being of all people and communities are essential to a thriving, equitable society.” Achieving this goal involves “eliminating health disparities, achieving health equity, and attaining health literacy.”

The Office of Minority Health (OMH) under HHS is tasked with research, investigations, and data collection; shaping policies, programs, and practices that raise public awareness; and building networks, coalitions, and partnerships. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) reauthorized OMH in 2010 and further established Offices of Minority Health within six other HHS agencies: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Food and Drug Administration, and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

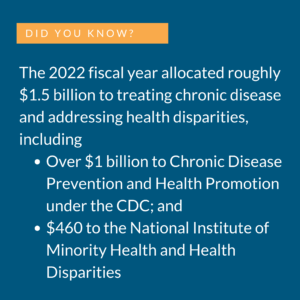

The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) under the National Institutes of Health (NIH) also “raises national awareness about the prevalence and impact of health disparities” through research programs, publications, and partnerships that focus on “effective individual-, community-, and population-level interventions to reduce and encourage elimination of health disparities.” The National Advisory Council on Minority Health and Health Disparities, composed of community representatives, health professionals, and subject matter experts, advises the HHS Secretary and the NIH and NIMHD Directors on health disparity issues and approves proposed research concepts, so the scientific community knows which areas of special interest are being considered for funding. See the members of the council here.

The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) under the National Institutes of Health (NIH) also “raises national awareness about the prevalence and impact of health disparities” through research programs, publications, and partnerships that focus on “effective individual-, community-, and population-level interventions to reduce and encourage elimination of health disparities.” The National Advisory Council on Minority Health and Health Disparities, composed of community representatives, health professionals, and subject matter experts, advises the HHS Secretary and the NIH and NIMHD Directors on health disparity issues and approves proposed research concepts, so the scientific community knows which areas of special interest are being considered for funding. See the members of the council here.

Congress

In the legislative branch, a number of committees influence health care through oversight and spending allocation.

In the Senate:

- The Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor, and Pensions has jurisdiction over most of the agencies, institutes, and programs under HHS.

- The Senate Committee on Finance, including the Subcommittee on Health Care, has jurisdiction over programs including Medicare and Medicaid, and other HHS programs financed by taxes.

In the House of Representatives:

- The Committee on Oversight and Reform oversees federal agencies, with the Subcommittee on Healthcare, Benefits, and Administrative Rules overseeing those agencies responsible for health.

- The House Committee on Energy and Commerce, and particularly its Subcommittee on Health, has jurisdiction over consumer protection, food and drug safety, public health research, and environmental quality.

State and Local

Each state, territory, and even community has specific needs that require carefully tailored and individualized approaches to identify and address health disparities. The Office of Minority Health (OMH) has partnership grants for the state and tribal health offices and agencies to address health disparities and promote health equity.

According to the Association of State and Territorial Offices (ASTHO) health equity state snapshots, there are (as of 2019 data):

- over 2,000 independent local health agencies;

- 99 independent regional or district health offices;

- over 600 state-run local health agencies;

- over 325 state-run regional or district offices.

You can find and reach out to your state’s minority health contacts here. See the profile for your state’s or territory’s public health agencies here.

Partnerships to improve health equity (either through public/private partnerships or collaborations between public agencies) are plentiful, but data is not always available: the last time the Office of Minority Health released a report addressing health disparities was 2016. they lack ways to evaluate their effects: “the development of meaningful metrics and objective measurement of their partnerships’ impact on improving community health.”

Additionally, while federal grant support is often important in the short term, it is rarely a long-term source of funding for ongoing operations. A majority of states participated in the State Partnership Initiative, but those partnerships only ran from September 2015 to July 2020. Partnerships have also seen unsteady levels of funding over the last decade: grants to improve minority health that ran from 2010-2013 allocated $5.9 million across all states; grants to address health disparities that ran from 2015-2020 allocated $4.1 million across all states.

The Private Sector

Non-government hospitals, universities, and community organizations play a large role outside of partnerships with the public sector. Faith-based and other community organizations help empower individuals at the local level and bring these individuals together to act collectively. The private sector also has the potential to improve employee health by communicating with employees to determine how to best promote health equity among employees, and what existing community resources may support this endeavor. For example, the Community Outreach and Patient Empowerment Program partners with the Navajo Nation Community Health Representative Outreach Program, bringing in health care teams and community advocates to create programs that focus on barriers and gaps in the community health care system. In partnership with the Alaska Tribal Health System, the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium provides for the health and wellness of Alaska Native and American Indian people through medical services, disease research, and even sanitation systems construction.

The University of Michigan’s Library has compiled resources, publications, and research on health disparities in the U.S., including a list of health equity organizations and resources.

Challenges and Areas for Reform

Social Determinants of Health

The CDC estimates 60% of premature deaths in the U.S. can be associated with nonmedical factors – the social, environmental, and behavioral influences known as the social determinants of health. In total, these factors, relating to housing, communities, social isolation, education, employment, diet, and physical activity, among others, account for at least 80% of health outcomes.

The CDC estimates 60% of premature deaths in the U.S. can be associated with nonmedical factors – the social, environmental, and behavioral influences known as the social determinants of health. In total, these factors, relating to housing, communities, social isolation, education, employment, diet, and physical activity, among others, account for at least 80% of health outcomes.

Clinical Care

The timely use of health care services helps achieve greater health outcomes for individuals and communities, but barriers to clinical care due to lack of available resources hinders more positive health outcomes.

Health Deserts

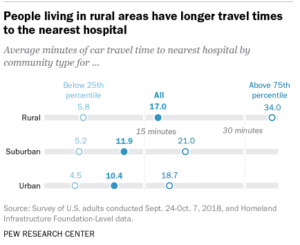

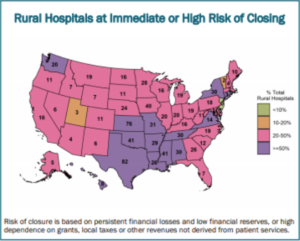

In the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine’s Roundtable on the Promotion of Health Equity and the Elimination of Health Disparities, participants addressed “‘health deserts’ – regions that have no hospitals and very few physicians.” Many hospitals, particularly in low-income communities and rural areas, “are under intense financial pressures, and many have closed down, because they cannot remain financially viable.”

In Washington, D.C., for example, there is only one hospital south of the Capitol; it alone serves “a very large, predominantly lower-income population.” Rural America saw 100 hospitals close between 2013 and 2020, and almost 900 hospitals are at risk of closing. Hospital closures have left many rural communities more than an hour’s drive away from the nearest emergency room, and a limited number of ambulances must be spread thin over larger and larger areas. This travel time can mean the difference between life and death in emergency situations: one study of hospital closures in rural California identified a 5.9% increase in mortality rates in the affected communities.

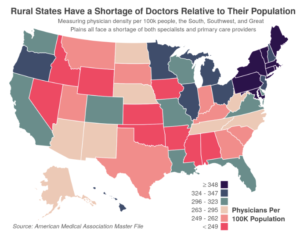

Physician Shortages

According to the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC), the U.S. population will need more doctors over the course of the next decade. The aging U.S. population will continue to grow and increase the number of Americans living with chronic conditions. Additionally, current doctors and physicians will also start retiring; about one-third of currently practicing doctors will be older than 65 within ten years. In total, the AAMC study expects a physician shortage of nearly 140,000 clinicians by 2033. The study also notes, however, that more important than an overall shortage is the “marked maldistribution of doctors;” while rural and urban underserved areas are already experiencing physician shortages, there are surpluses of doctors and specialists in affluent communities.

The coronavirus pandemic made the challenge of physician shortages an immediate concern. A number of states addressed these shortages by modifying their licensing laws to allow healthcare personnel to offer their services across state lines. Temporary changes in licensing and patient privacy laws also increased use of telehealth services in an effort to provide non-urgent care to patients in their homes. Telehealth has been most impactful for expanding access to mental health and substance abuse resources. Telehealth accounted for 10% of overall doctors’ visits in spring 2020, but 40% of mental health appointments. These strategies in the long term could serve as “effective means to reach medically underserved” populations.

Health Behaviors

Health behaviors “are actions taken by individuals that affect health or mortality,” such as smoking, physical activity, sleep, or adherence to medical treatments. These behaviors are linked to personal responsibility just as much as they are to social and economic conditions that shape or limit choice. For example, there are “‘statistically significant negative relationships’ between active travel (walking and cycling) and self-reported obesity as well as between active travel and diabetes.” However, available infrastructure (roads and sidewalks) and community safety can influence personal decisions about active travel.

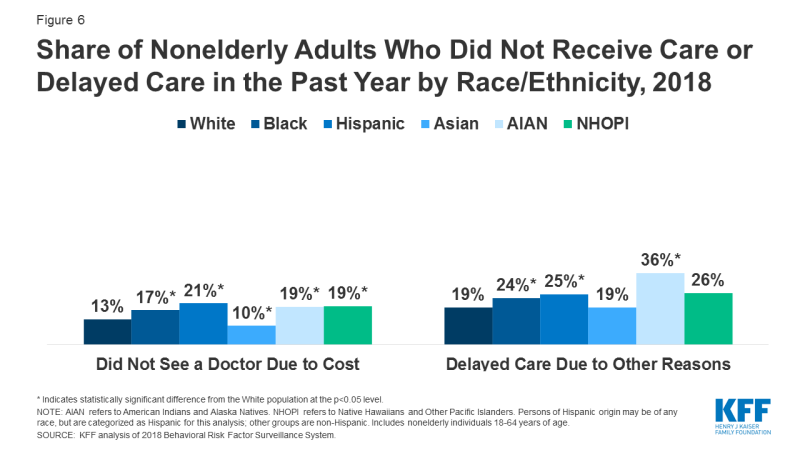

Seeking medical care is another health behavior that depends on a number of factors. The U.S. Federal Reserve reports that 25% of U.S. adults that skipped medical care in 2019 cited cost as the reason, even among those with health insurance; high out-of-pocket expenses and deductibles that consume significant portions of income leave many with inadequate insurance. The Policy Circle’s Health Care Reform Brief further breaks down the effects of cost and underinsurance.

HHS also found the LGBTQ community faces barriers to accessing care, ranging from “exclusion from a partner’s health insurance, provider-related discrimination… and poor matches between the needs of LGBT people and the kinds of services that are available.” The coronavirus has been another factor influencing access to and whether or not people seek out care. A study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association looking at excess deaths during the coronavirus pandemic in the U.S. in March and April found “[l]arge increases in mortality” from chronic conditions including heart disease and diabetes “caused by disruptions in society that diminished or delayed access to health care and the social determinants of health.”

Lack of Trust

Lack of trust in the healthcare system is an important but often overlooked factor. In an Emory University study, Hispanic and black respondents “were more likely to report believing that doctors don’t see them as equals or were less concerned for their wellbeing.” Another research initiative by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation found that low-income patients, uninsured patients, family caregivers, and non-English speakers all “reported widespread distrust of the health care system and the feeling they were seen as ‘less than’ by health care professionals” on the basis of their income, insurance status, and race. Physician behaviors such as “brushing off patient concerns and symptoms, and ignoring adverse events that patients reported from prescribed treatments” have been linked to “stereotypes, racial profiling, and implicit bias,” according to the Association of American Medical Colleges. On the patient side, histories of biases and poor treatment, such as in the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, have contributed to and perpetuated mistrust.

Rebuilding confidence in the health care system requires an understanding among health care professionals that trust is not automatically “conferred on the physician along with degrees and professional credentials.” Training doctors to be aware is a fundamental component of addressing the social determinants of health. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), a private, nonprofit organization that reviews graduate medical education programs and their sponsoring institutions, has made sensitizing medical students and fellows to health inequities a priority in its accreditation system. This includes clinical learning environment reviews (CLERs) and getting regular feedback not only from faculty members and medical staff but also from family members and patients. Programs involve identifying health disparities in the clinical site’s surrounding community and developing “cultural competencies relevant to the patient population served by the clinical site.” In the ACGME’s 2019 report on CLERs, they found residents and fellows were aware of and able to identify health disparities in the populations served by the clinical site, and they incorporated this knowledge when providing direct health care services.

The Florida International University NeighborhoodHELP program tried something similar. See highlights of the program here (4 min):

Social, Environmental, and Economic Factors

Education & Health Literacy

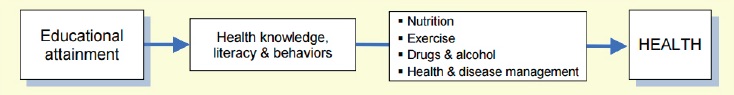

When looking at the root causes of health inequities, the NIH has found correlations between overall levels of educational attainment and certain health indicators and behaviors, including life expectancy, obesity, smoking, and alcoholism. Among working men who self-reported having fair to poor health, research from the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) revealed a 16% gap between those with less than a high school education and their college-educated counterparts.

American adults with a four-year college degree live 3 years longer than Americans without college degrees. Since 2012, life expectancy for American adults without a college degree has been declining. Many point to declining economic prospects for those without post-graduate education, highlighting the increasing number of “deaths of despair” – drug overdoses, suicides, and alcohol-related health issues that are concentrated among middle-aged white Americans without college degrees.

Educational attainment greatly affects knowledge of how to “access, understand, appraise, apply and advocate for health information and services,” referred to as health literacy. A health literacy meta-analysis found lower levels of health literacy correlated with “increased hospitalizations, greater emergency care use, lower use of mammography… poorer ability to interpret labels… and, among seniors, poorer overall health status and higher mortality.” In fact, the study also found evidence that health literacy “potentially mediates disparities between blacks and whites.”

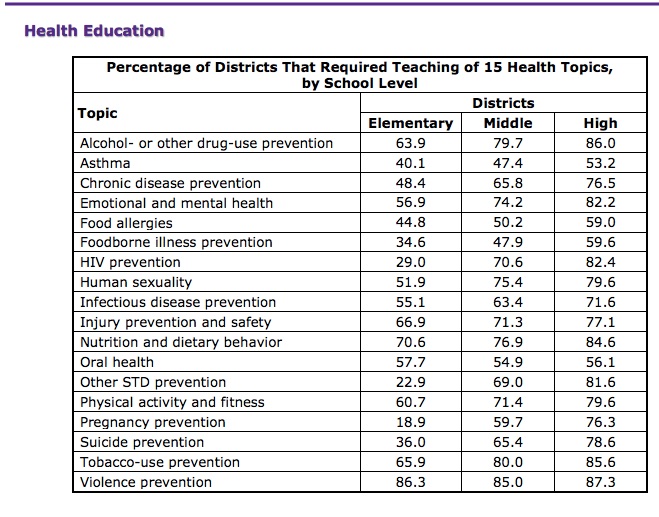

Many children and young adults learn about health in schools. The CDC’s Healthy Youth School Health Policies and Practices deems 15 topics essential for students to comprehend, but not all schools across the country require all topics to be taught. Across the country, roughly 40% of schools require students in grades 6 through 12 to take a health education course in order to graduate. Outside of school, “[f]amily values, behaviors, routines, and decisions, borne out of the recurring patterns of interactions within and outside the home,” also affect children and young adults’ understanding of the health care system and health-promoting behaviors. For example, family eating habits can improve children’s eating habits; frequency of shared family meals is related to lower levels of obesity, disordered eating, and healthy eating patterns in children.

Many children and young adults learn about health in schools. The CDC’s Healthy Youth School Health Policies and Practices deems 15 topics essential for students to comprehend, but not all schools across the country require all topics to be taught. Across the country, roughly 40% of schools require students in grades 6 through 12 to take a health education course in order to graduate. Outside of school, “[f]amily values, behaviors, routines, and decisions, borne out of the recurring patterns of interactions within and outside the home,” also affect children and young adults’ understanding of the health care system and health-promoting behaviors. For example, family eating habits can improve children’s eating habits; frequency of shared family meals is related to lower levels of obesity, disordered eating, and healthy eating patterns in children.

Building educational skills and health literacy skills can empower individuals with the necessary resources to advocate for their health. The Project SHARE Curriculum (Student Health Advocates Redefining Empowerment), an endeavor by the University of Maryland, Baltimore, “aims to build high school students’ skills to reduce health disparities at the personal, family and community level.” In addition to standard health topics such as nutrition, the curriculum includes lessons on the social determinants of health, how to locate and evaluate health information, and how to understand family health history. By equipping students with this knowledge, the program hopes to promote health and wellness in the surrounding community. Outside of schools, HHS’s National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy recommends infusing health literacy skills into curricula for adult education, ESOL, and family literacy programs. This can involve community partnerships that bring medical librarians or health professionals to classes as guest lecturers.

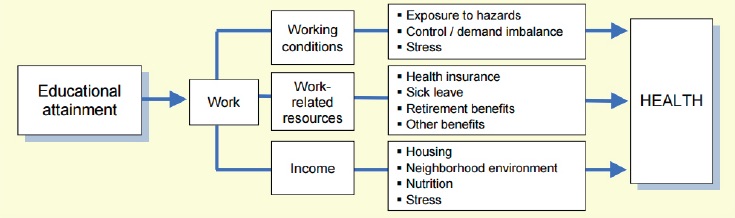

Employment and Income

Educational attainment also has a strong effect on employment opportunities and related factors of income and working conditions. AEI’s Health and Poverty study notes the correlation between education, employment, and income: “low-skilled and low-income workers are more likely to find themselves in jobs that do not support good health.” This can be in terms of physical environments, such as in the agricultural or construction sectors, where workers face numerous safety, environmental, and respiratory hazards. Jobs that do not support good health can also reflect salary, security, or health and social benefits.

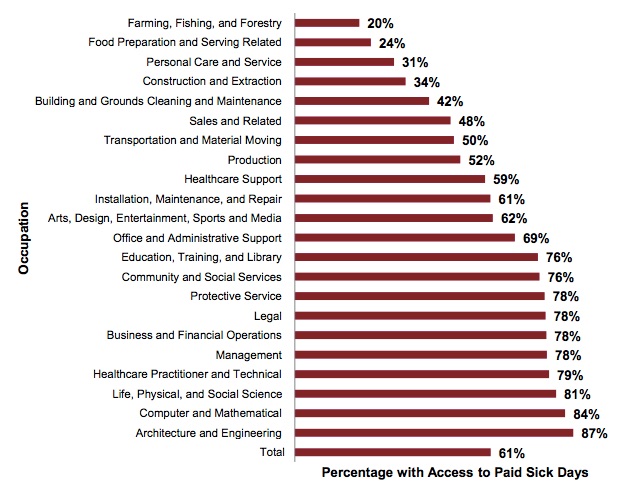

Inequities in employment are also associated with demographics. For example, Hispanic workers comprise 17% of the workforce but account for over 50% of both the agricultural workforce and the construction industry, and are much less likely than white, Asian, and black workers to have access to paid sick leave. Black workers make up 12% of the workforce but 25% of service industry employees, and less than one-third of workers in service-related occupations have access to paid sick leave. Overall, only 46% of black workers and 41% of Hispanic workers have access to employer-sponsored health insurance, compared to 66% of white workers.

When it comes to unemployment, individuals who lose their jobs “are 54 percent more likely to report that they are in fair or poor health and 83 percent more likely to develop a stress-related health condition such as heart disease or stroke.” Stress in and of itself is an important player: “Unemployment, precarious employment, and employment conditions continue to be routinely linked to increased psychological distress.” Unemployment rates for black workers, American Indian and Alaska Native workers, and Hispanic workers are consistently higher than unemployment rates for white workers.

By providing nearly 180 million employees and family members (56% of the population) with employer-based insurance, the private sector has an important role in employee health. Economic opportunity, workforce development and growth programs, employee health and wellness programs, and healthy work environments and policies all have the ability to foster healthier, more productive employees, which in turn promotes overall economic growth.

The Business Group on Health is an organization that addresses health care issues facing employers, focusing on health care policy, creating sustainable employee well-being programs, and designing leave programs. Current members include Aetna, LabCorp, Allstate, FedEx, Fitbit, and Marriott International, among many others. Marriott International’s TakeCare program focuses on providing employees with opportunities to make healthy choices through fitness challenges, nutrition lessons, stress management techniques, and financial well-being services. In 2019, the program was extended from Marriott’s properties to associated organizations, teams, and communities.

Environment

Where people work, live, and spend considerable amounts of time greatly affects their sense of security, well-being, and opportunities. Unsafe streets and highways can present health issues for people who would otherwise walk or cycle for transportation or exercise, and the presence of environmental hazards such as pollution, second-hand smoke, or unclean water have negative consequences on health and well-being.

Aging infrastructure like lead-lined pipes and older housing stock with lead paint puts 2.6 million Americans at risk of lead poisoning, which can cause infertility and developmental issues in young children, because of lead found in paint chips or lead-lined water pipes. To address this issue, the Biden Administration’s 2021 Infrastructure Bill allocated $3 billion in funding to replace lead-lined pipes and housing with lead paint across America. See The Policy Circle’s Water & Power Brief for more on this topic.

Asthma symptoms can also be linked to where families live and the physical environment of their homes. A study from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that black and Hispanic communities experience disproportionate exposure to pollution from industrial facilities, and that “the share of exposure risk born by blacks and Hispanics generally exceeds their share of employment at the polluting facilities.”

Small interventions can make big differences. In Washington, the Seattle-King County Healthy Homes Project connected community health workers to low-income families with children with uncontrolled asthma. When these workers conducted regular home visits, the families’ use of urgent care services fell by almost two-thirds. Social supports are important components of community environments; exposure to crime or violence can influence feelings of safety and security, and hinder social cohesion. Interventions that build social cohesion can serve as part of larger community care management efforts. Los Angeles County’s Gang Violence Reduction Initiative began the Parks After Dark program in 2010, focusing on areas of high crime during the summers when schools are closed and youths have fewer opportunities for recreation and social activities. The program extends parks’ evening hours and offers various programs to community members from cooking classes and concerts to organized sports and resource fairs. Entire families across communities have participated, allowing police officers to build trust and establish relationships with community members. Violence fell by almost 50% in the first four years.

Nutrition

In the U.S., the 10 counties with the highest numbers of food-insecure households all spanned urban cities, including Chicago, Phoenix, Los Angeles, Houston, and New York. Limited access to grocery stores also exists in rural areas. Predominantly black and Hispanic neighborhoods also frequently have fewer supermarkets and grocery stores than predominantly white and non-Hispanic neighborhoods; instead, these areas tend to rely on convenience stores that generally have less variety of foods, inferior produce, and higher prices. These regions that “often feature large proportions of households with low incomes, inadequate access to transportation, and a limited number of food retailers providing fresh produce and healthy groceries for affordable prices” are called food deserts.

Fewer supermarkets makes accessing healthier foods difficult. And, says Nancy Roman, President and CEO of the Partnership for a Healthier America, the issue is not just “lack of access to nutritious food like fruits and vegetables… it is excess supply of processed foods with added sugar and high levels of sodium.” Part of this excess is related to federal agricultural subsidies. The most heavily subsidized crops – corn, soy, wheat – are primarily used to make ultra-processed foods, such as those with sweeteners like high fructose corn syrup.

Both food insecurity and poor diet are associated with higher rates of chronic diseases such as cancer and diabetes, hypertension, obesity, and, in children, birth defects and developmental problems. The opposite is also true; the University of Washington Center for Public Health Nutrition found closer proximity to supermarkets was related to consumption of more fresh produce, lower levels of obesity and diabetes, and lower body mass index.

In California, South Los Angeles-based start-up Everytable started in 2016 as a grab-and-go restaurant targeting “low-income food deserts and populations which might otherwise only have access to fast food. Six years later, the company has locations across Los Angeles where meals cost as little as $5 in an effort to provide healthy, chef-prepared meals inexpensively. Sourcing directly from farms and preparing food in-house helps keep costs low, and partnering with institutions such as the City of Los Angeles helps get food to vulnerable individuals.

Impacting food insecurity goes beyond access; when people are more involved in the growth, purchase, preparation, consumption, and sharing of food, it changes the way they interact with food. The Delta Health Center, which in 1965 became the first rural Federally Qualified Community Health Center, serves the communities in the Mississippi Delta. The Center’s Community-Oriented Primary Care Model community development projects that improve health, including an agricultural co-op. Combining skills and resources with a local university and with local community members, advocates, growers, and food retailers through the Delta Fresh Foods Initiative, the co-op produces fruits and vegetables on almost 7 acres of land. Not only are healthy foods available, but consumers are actively encouraged to take part; for example, diabetes patients that visit Delta Health Center clinics receive a ticket that allows them to access produce on the farm, at no cost.

Ron Finley, the “Urban Gangsta Gardener,” started growing his own food on a small strip of grass outside his home in South Central Los Angeles. His project helps communities “embrace the act of growing, knowing and sharing the best of the earth’s fresh-grown food.” See his story (5 min):

Obesity

Closely related to nutrition is one of America’s greatest health challenges: the rising rate of obesity. Between 2017 and 2020, the U.S. obesity prevalence was 41.9%, up from 30.5% from 1999-2000. The rate of severe obesity increased from 4.7% to 9.2% over that time period. Black Americans (49.9%) had the highest prevalence of obesity, followed by Hispanic Americans (45.6%), White Americans (41.4%), and Asian Americans (16.1%).

“The association between obesity and income or education level is complex,” according to the CDC. Men and women with college degrees on the whole had lower rates of obesity when compared to those with less education. However, among men, obesity prevalence was lowest among the low-income and high-income groups, as compared to the middle-income groups. Such statistics make it difficult to make generalizations.

For Americans ages 2-19 between 2017 and 2020, the prevalence of obesity was 19.7% and affected about 14.7 million children and adolescents. Prevalence was 26.2% among Hispanic American children, 24.8% among Black American children, 16.6% among White American children, and 9% among Asian American children.

Obese children are 5x more likely to become obese as adults. However, regular childhood physical activity through sports and recess can build lifelong healthy habits: physically active children tend to move more as adults. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that children get 60 minutes of physical activity per day, but only a quarter of children have this level of physical activity, and many states don’t require a minimum level of physical education or recess time.

A growing number of community groups across America have formed to address a lack of physical activity among Americans of all ages. Bartendaz, a group that began in New York City, is making activity accessible to people without gym memberships by promoting bodyweight works with calisthenics movements like pull ups that require very little equipment.

Community-based Solutions

Communities are “the bedrock of health, shaping lives and behaviors.” What is prevalent in communities is prevalent among community members; in areas with more liquor stores, for example, alcohol consumption rates are higher. The reverse can also be true – making health and well-being a shared vision and value starts in communities. Consequently, addressing health inequities requires community input; local stakeholders are most impacted by interventions, and as such have firsthand knowledge of which policies and programs are working, which determinants of health are of greatest concern, and which community strengths and resources can be built on. Health Impact Assessment (HIA) tools help analyze the effects of proposed interventions and policies by incorporating data from local stakeholders in the community.

Watch how the Indianapolis Congregation Action Network (IndyCan, now Faith in Indiana), used their community-based knowledge (4 min):

Conclusion

Addressing health inequities requires a holistic approach that considers all factors impacting health and well-being. Programs that engage all stakeholders in communities – schools and small businesses, faith-based institutions and nonprofit organizations, health care professionals and law enforcement personnel – can best serve the community. These stakeholders have the first-hand experience necessary to speak to the determinants that have the greatest impact on population health, and can act as partners in facilitating solutions to help make health and wellbeing a community value.

Addressing health inequities requires a holistic approach that considers all factors impacting health and well-being. Programs that engage all stakeholders in communities – schools and small businesses, faith-based institutions and nonprofit organizations, health care professionals and law enforcement personnel – can best serve the community. These stakeholders have the first-hand experience necessary to speak to the determinants that have the greatest impact on population health, and can act as partners in facilitating solutions to help make health and wellbeing a community value.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Find out what your state and district are doing about health disparities in your communities.

- Do you know the state of health inequities in your community or state? What unique challenges exist in your community?

- How does your community rank on the County Health Rankings?

- What are your state’s policies addressing health disparities?

- Is there a task force or project in existence, or does one need to be formed? See what’s going on in your community.

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Who are the members of task forces or coalitions in your state and community?

- Who promotes or delivers health-related education in schools and for adults?

- What steps have your state’s/community’s elected/appointed officials taken?

- Who is your State’s Minority Health Contact?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement.

- Engage with coalition members at the local, state, and national levels.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with law enforcement, first responders, faith-based organizations, local hospitals, local businesses, sports clubs, and community organizations

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, communications@thepolicycircle.org, for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policymakers, and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Create a Health Equity Action Plan for your community.

- Fill out your plan with this 7 step guide.

- Use a Health Impact Assessment tool to consider the effects of a proposed policy.

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.