Each state offers various amenities and lifestyles, from tax rates to climate. In the United States, we have the freedom to move within our state or move to a different one. Domestic migration patterns have shifted in the last decade. Where are people leaving from and where are they going? What are the factors driving people away from, or towards, a certain location? What are the effects of state to state migration and how does it affect the country as a whole?

Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

Case Study

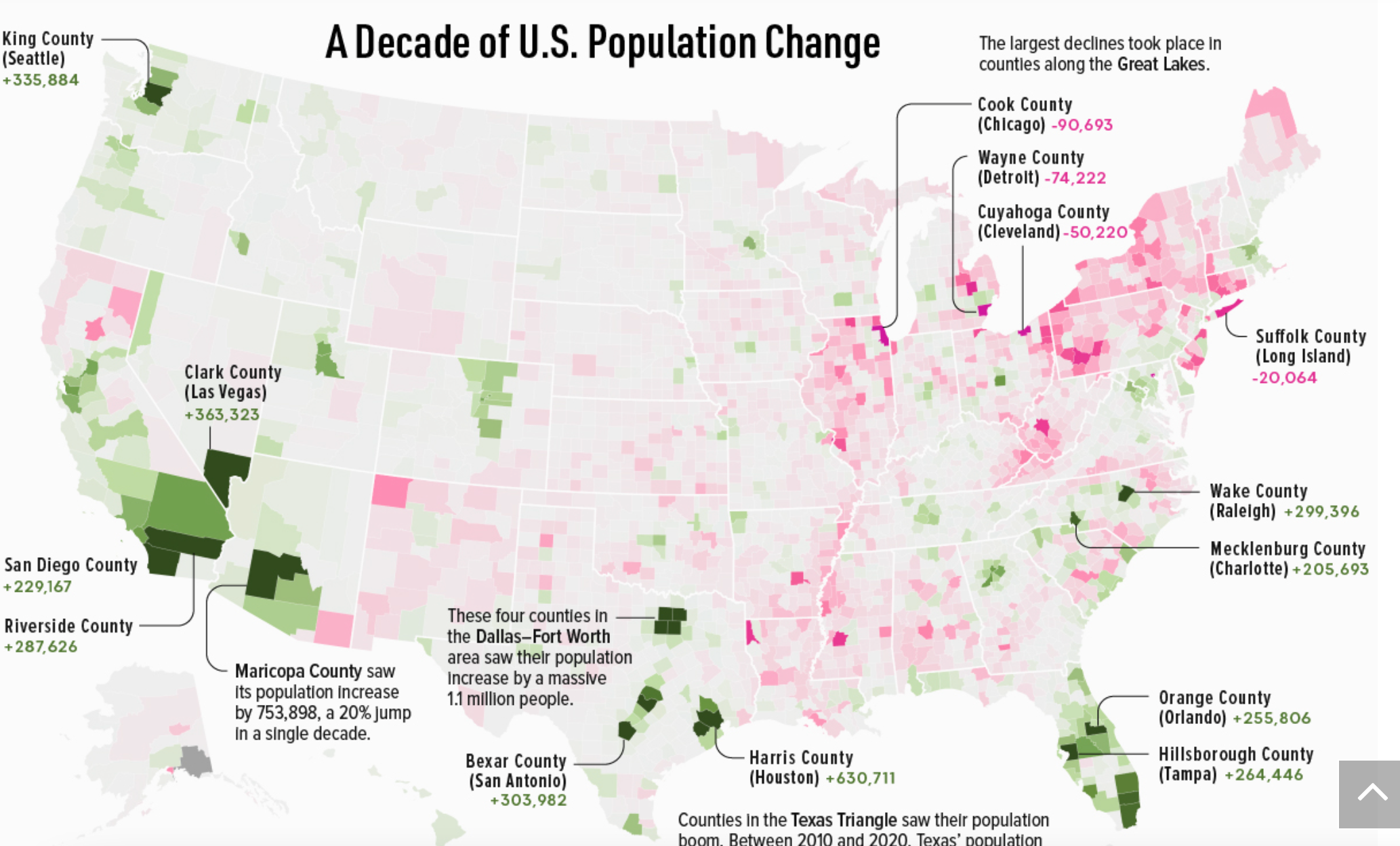

The 2021 Census Estimate reveals the total U.S. population growth slowed to 0.1%, the lowest in U.S. history. This is a significant decrease from 7.5% between 2010 and 2021; second to the slowest growth on record during the Great Depression. The decrease in the overall national population growth impacts state population, which is further impacted by migration between states.

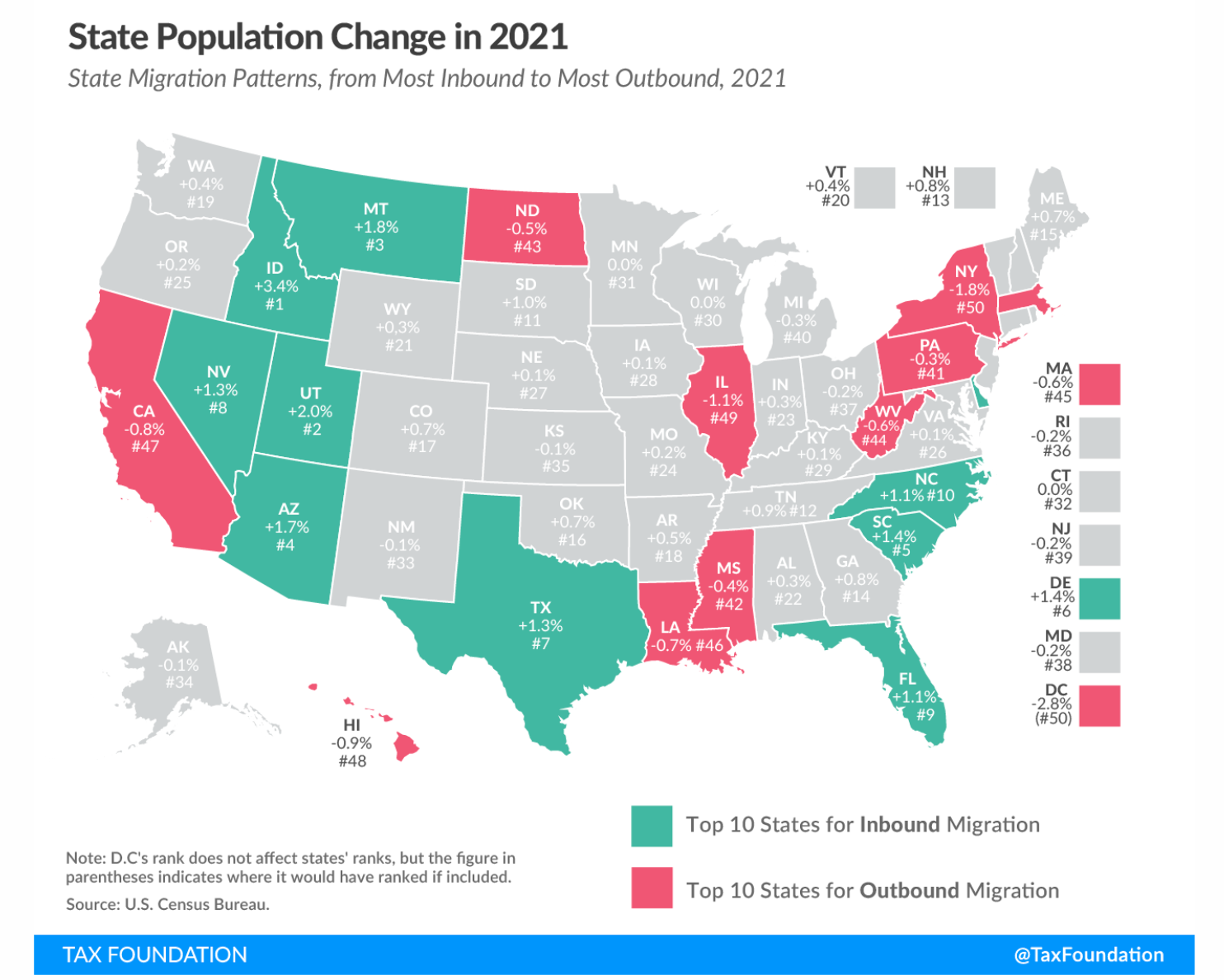

Population increases and decreases has a wide scope of repercussions. For the first time in its 170 years of statehood, California lost a congressional seat after the 2020 census.The loss is the result of a decrease in the state’s population caused by slow population growth and an exodus of residents moving elsewhere. New York state also lost a congressional seat by only 89 residents according to the 2020 census. “With that number – the amount that could fill a single New York City subway car during off-peak hours – the state would have stopped its eight-decade streak of declining congressional representation.”

Meanwhile, Texas, Florida, and Colorado all gained Congressional seats in 2020, reflecting Americans “continued their march to the South and West,” and away from “one-time engines of growth” such as New York and California. These electoral shifts “reflect the decade’s broad population shifts: slow growth in the Northeast and Midwest, and gains in the South and some Western states.”

Why it Matters

As New York and California demonstrate, small population shifts between states can influence a state’s political representation on the national stage. Additionally, states with an outgoing population encounter decreases in their tax base, a workforce shortage, and a drain on intellectual capital. On the other hand, states with a booming population encounter potential new challenges to state infrastructure with “increased traffic, rising home prices and strains on an infrastructure already grappling with climate change.”

U.S. federalism allows each state to determine its own policies driven by the needs of its residents and local concerns. Migration patterns shed light on what draws people to some places and pushes them away from others. This reflects the idea of voting with your feet: the ability to exercise political freedom to decide what policies people want to live by. Determining which policies work and which do not helps policy makers determine key factors that need short and long term attention towards solutions.

Putting it in Context

History

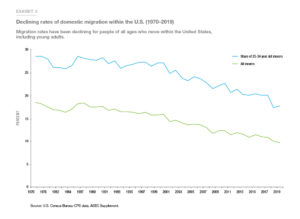

Americans do not move as much as they used to. In the post-World War II era from the late 1940s to the 1960s, Americans changed residence annually due to economic prosperity and a demand for housing among the young population. Over the next few decades, a number of factors contributed to fewer people migrating each year: the increase of dual-earner households, an aging population, and labor markets to name a few. In 2021, domestic migration rates fell to a new low of 8.4%, a continuation of a pre-pandemic trend in the US.

From 2005 to 2010, local mobility, a change of in-state residence within counties, accounted for 8-9%, dropping to 5.4% since then. As local mobility accounts for about 60% of all moves, it drove the overall downward trend. Interstate movement stood at 5-6% in the 1990s and averaged 3.5% since 2007; yet migration rates fell from 12% to 8.4% between 2010 and 2022.

Historically, young adults between the ages of 18-34 are the most mobile class of Americans and drive overall migration trends. While this age group still accounts for most state to state migration, issues “associated with higher housing costs and underemployment” led many to postpone milestones, such as homeownership, which lowers the overall domestic migration rates.

Motives

More than half of local movers say housing is a reason to move – movers want new, better, or more affordable options. According to an Axios poll of just over 1,000 respondents, 63% of Republicans and 45% of Democrats indicated cost of living as their reason to consider a move, followed by 27% of Republicans and 35% of Democrats citing personal/family reasons. Both political affiliations in this poll tied at 25% for jobs/employment as a consideration for a state to state move.

One overlooked factor is that job-related moves could be housing-related if people are unable to move for work due to housing factors. However, fewer people who change jobs actually move. Job-related moves may be due to housing if jobs are scarce and housing is limited. In 2017, 90% of people who changed jobs did not move, an increase from 82% in 1980.

COVID-19

COVID-19

The coronavirus pandemic spurred people to consider moving for better housing options, living near family, and job-related opportunities. The sudden switch to remote work provided employees a different way to work. It also prompted some to consider it as a permanent option because they enjoyed the flexibility and were no longer required to live where their employers were located.

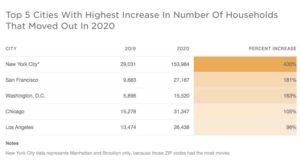

More than 7 million households moved between counties in 2020, half a million more than in 2019. Many local movers chose to move from major cities into the suburbs, to smaller cities and even to rural areas with far lower cost of living.

Pew Research surveys conducted in June and November of 2020 found the reason for pandemic-related moves shifted considerably in just a few months. In June, pandemic migrants cited risks of getting the coronavirus, while those surveyed in November cited financial stress.

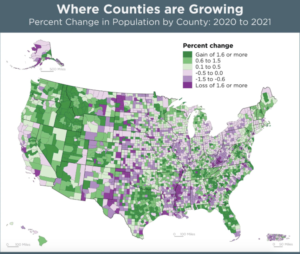

The trend continued into 2021. Census data shows 65.6% of American counties saw an increase in population as Americans moved from larger cities to smaller ones. A report by the Economic Innovation Group found the nation’s largest urban counties lost more than 860,000 residents in 2021, while the fastest growing counties were suburban and exurban.

Nationwide Changes

Housing Markets & Resources

A variety of factors put pressure on the U.S. housing market “including incomes that haven’t kept up with housing costs increases and a housing construction slowdown.” In January 2022, active housing listings in the U.S. dropped to its lowest in five years. Limited supply, coupled with rising demand, pushed housing prices up. According to Money.com, home prices rose over 20% in just one year with Arizona topping the chart at 32.6%.

Adding to this are lack of labor challenges, land-use regulations, raw material costs, and lack of available lots. In these growing markets, the undersupply of housing “is leading to speculative booms.” According to the WSJ/realtor.com index, home prices in the top 10 markets rose 27% on average in 2020, compared to the nationwide average rise of 14%.

Residents from more expensive markets can likely buy homes with cash which threatens to price-out other home buyers and, possibly, the people already living there. These individuals may be forced to move farther away from major areas in search of less expensive housing. In turn, labor markets, local economies, and infrastructure are affected by a change in the local population. More people coming into a community than are leaving causes additional burdens on infrastructure such as public transportation, increased road driving, health care needs, and families enrolling children in public schools. On the other hand, a population influx presents an opportunity for investment by bringing new businesses to increase commerce while supporting local businesses, restaurants, etc.

Contracting markets have excessive inventory due to out-migration which leads to “a slowdown in house price appreciation.” In large cities where people are leaving, the result is double-digit rent decreases and subsequent decrease of billions of dollars of annual property tax revenue. Property taxes in 2018 accounted for 30% of local government revenue, which resulted in subsequent cuts to local spending. The public sectors most affected include elementary and secondary education, public health and hospitals, and roads and highways. In contrast, growing populations generally indicate a strong labor force which fuels economic activity to generate tax revenue, fund increased spending on infrastructure, education, and government services. PEW Research details the top states that gained and lost residents in 2021.

See what’s happening to inventory and property listing prices in your community from WSJ.

Economics

Operating on the assumption that Americans and U.S. companies alike “‘vote with their feet’” when people or companies move between states. Migration patterns based on economic factors include the ease of doing business and tax burdens. For example, in terms of fiscal stability (including state credit ratings, public pension liabilities, and state budget management), four of the top ten outbound states were among the five states with the worst fiscal stability rankings. The Tax Foundation shows state population changes here:

These migration patterns continued to develop. Texas and Florida, two states that saw the biggest net migration gains, do not have income tax. According to the Illinois Policy Institute, many Illinois residents – who pay the highest effective local and state tax rates in the country – made the short move next door to Indiana or Wisconsin. Indiana has a low flat tax and low property taxes, while Wisconsin has fully funded pensions and generous tax credits.

As this WSJ article explains, “Suburbs are emerging as the winners from these changes, marking the end of a decade-long growth trend for big cities. Companies intent on lowering overhead and retaining talent are opening offices there, and developers are adding amenities to keep entertainment dollars local.”

The Tax Foundation’s 2022 State Business Tax Climate Index shows the two worst performing states on the index are also in the top ten states with the most outbound migration (e.g. New York and California). Meanwhile, seven of the ten states with the most inbound migration are in the top half of states on the index.

These data points indicate the cost of living or operating a business are major factors of consideration when individuals decide to relocate. Areas that are more difficult to start or conduct business are likely to see a drain on intellectual capital as entrepreneurs take their businesses elsewhere. Areas where workers take home fewer earnings due to taxes are likely to see a shortage in the labor market as workers move to areas where their earnings go farther. Meanwhile, areas with policies that encourage and foster business development are likely to attract individuals in search of business opportunities, either to start their own or to join an active and flourishing business sector and labor market. Research by the George W. Bush Institute and Southern Methodist University (SMU) Economic Growth Initiative supports these assumptions and found that top performing metro areas have above average living standards, upward mobility opportunities for residents, affordability, strong social capital, and growth-friendly business and land-use rules.

Food Truck Roadblock from Free to Choose Izzit.org, shows the offering a food truck in Chicago, Illinois, one of the cities/states with the highest outbound migration rates (12 min):

Case Studies: Outbound Migration

Forbes lists the following as the top three states with the highest rate of people moving out. Below is a snapshot outlining some reasons why.

California

After experiencing significant growth between 1900 and 2000, California saw its slowest growth rates since 2000. This rate grew by 6.5% between 2010 and 2020 compared to the national average of 6.7%. During this time period, 1.3 million more people left California for other states than came to the Sunshine State from other states. From 2019 to 2020, the population grew by only 0.05%, with a net population loss of 500,000. The bulk of people moving to California are international immigrants. Meanwhile, from July 2020 to July 2021, San Francisco saw the largest rate of population decline among all U.S. cities (6.3%).

Between 2017 and 2018, Census Bureau data revealed California was the state with the most domestic outmovers. Those leaving are primarily middle-income residents. Millennials and working class individuals say even with good jobs, the commute and the paycheck-to-paycheck lifestyle are difficult. Lastly, people of retirement age whose homes have appreciated are selling and moving to live in states with lower taxes.

According to Census Bureau data, of adults who left California in the 2010s, 49% cited work-related reasons, 23% cited housing-related reasons, and 20% cited familial reasons. A 2019 UC Berkeley poll of registered voters found more than half of survey respondents considered leaving California; 71% mentioned high cost of housing and 58% mentioned high taxes. A survey by the Public Policy Institute of California in May 2021 found about a third of Californians “have seriously considered leaving the state because of housing costs.”

The cost of living in Los Angeles is 49% higher than the national average, with San Francisco coming in at 94% above the national average. Compared to other regions, California’s cost of living “remains an ongoing public policy challenge,” according to Hans Johnson, senior fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California. He further states that this issue “needs resolution if the state is to be a place of opportunity for all its residents.”

The WSJ dives into California’s rising home prices (5 min):

For more on rising home prices, see The Policy Circle’s Affordable Housing Brief.

Businesses and entrepreneurs are also among those leaving California to new locations with lower taxes and other business cost incentives, and, in fact, has been coined “The California Book of Exoduses.” This “Book” lists 172 (and growing) major businesses that left the state to house itself in another.

For more on rising home prices, see The Policy Circle’s Affordable Housing Brief.

Illinois

Over 1.6 million people left Illinois for other states from 2014 to 2018, up almost 16% from those who left the state between 2009 and 2013. In fact, Chicago is the only city “to suffer a drop in both people moving in and an increase in people moving out,” whereas other cities losing population have out-migration offsetting in-migration for a net loss. According to Illinoians, poor public policy has led many to consider leaving for better housing and job opportunities. Outgoing populations negatively affect a state’s economic prosperity.

The majority of those leaving are prime working-age residents looking for better jobs or housing opportunities. Census Bureau data reveals that between 2010 and 2019, 50% of adults ages 25-54 said they moved out of Illinois for work reasons and 20% for housing reasons. Census Bureau data also showed that individuals with higher levels of education were twice as likely to leave the state, indicating that primarily young, education professionals in their prime working years are mostly looking for better employment opportunities. According to the Illinois Policy Institute, residents already pay higher effective local and state tax rates than anywhere else in the nation.

New York

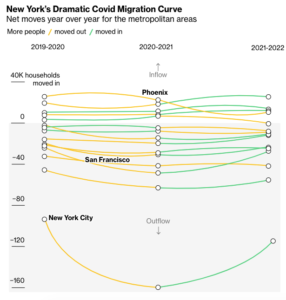

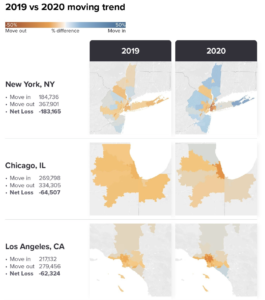

New York’s cumulative net domestic migration loss to other states since 2010 is over 1.5 million. Compared to other states, Census estimates say over 200,000 more residents moved out of New York state than in between July 2019 and July 2020. This was the highest amount in 14 years. In 2020, the state lost a net of 150,000 households, more than any other state and double the amount in 2019. Across all 50 of New York’s counties, only three gained population over the past decade.

Movement out of New York City, specifically, is even more noticeable. Data from the U.S. Postal Service shows that almost 250,000 of New Yorkers filed a change-of-address request to zip code outside of the city from March to October 2020, double the amount of requests during that period in 2019. This data is corroborated by Census data which estimated that between April 2020 and July 2021 NYC lost 300,000 people due to outmigration. Moves out of Manhattan and Brooklyn more than quadrupled between February and July 2020. Even though the city experienced a rebound in early 2022, overall, the population declined. This trend continues from the past decade where most NYC counties experienced out-migration.

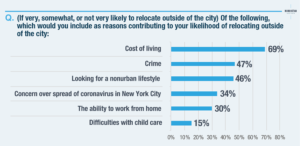

The desire to leave New York increased among high-income NYC residents and among those ages 18-44. According to a Manhattan Institute survey, in mid-2020, 44% of high-income NYC residents said they considered relocating over the summer of 2020, and 37% said it was somewhat likely they would not remain in the city past two years. The cost of living was the most common reason (69%), followed by crime (47%), and a desire for a non-urban lifestyle (46%). Additionally, 30% said the possibility of remote work makes it more likely to consider a move. The results of this survey are echoed today. According to data released by the IRS, NYC lost $21 billion in capital when some of its wealthiest citizens migrated to other states.

New York state taxes wages at 9% for earners making over $100,000. New York City places an additional 4% tax on wages. Therefore, the more income people make, the greater incentive they have to leave to a state with lower income tax rates. This is particularly true among Baby Boomers who accelerated plans to retire, like the number of New Yorkers who moved to Florida. Young professionals also found that remote work mitigated the advantages of urban life, and many entrepreneurs decided to take their businesses with them.

In the third quarter of 2020, the reduced demand for city apartments caused the median monthly rents to fall about 8%. This took pressure off housing prices for a period of time in one of the nation’s most expensive cities, but caused negative repercussions, like a drain of entrepreneurial and intellectual capital and decreased tax revenues. Since that time, the demand for city apartments has returned to NYC. This demand is met with rent increases and stalled development, yet, arguably, is a return to pre-pandemic growth which will naturally return lost capital and increase tax revenue to the city.

For more on different kinds of taxes and how they affect local budgets and individual wallets, see The Policy Circle’s Taxes Brief.

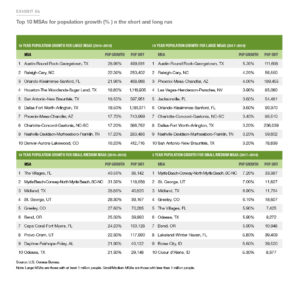

Case Studies: Inbound Migration

From 2017 to 2019, the population in the south and west regions of the U.S. grew at around seven times the growth rate in the northeast and midwest regions. Population growth was driven by domestic migration particularly in the south. In 2018, 1.2 million people moved to the south from regions, compared to 714,000 who moved from the south to another region. From July 2020 to July 2021, the fastest growing cities, with populations of at least 50,000, were in the Sunbelt metro areas: areas just outside Austin, Phoenix, San Antonio, and Fort Myers had growth rates between 6 and 10%.

Texas

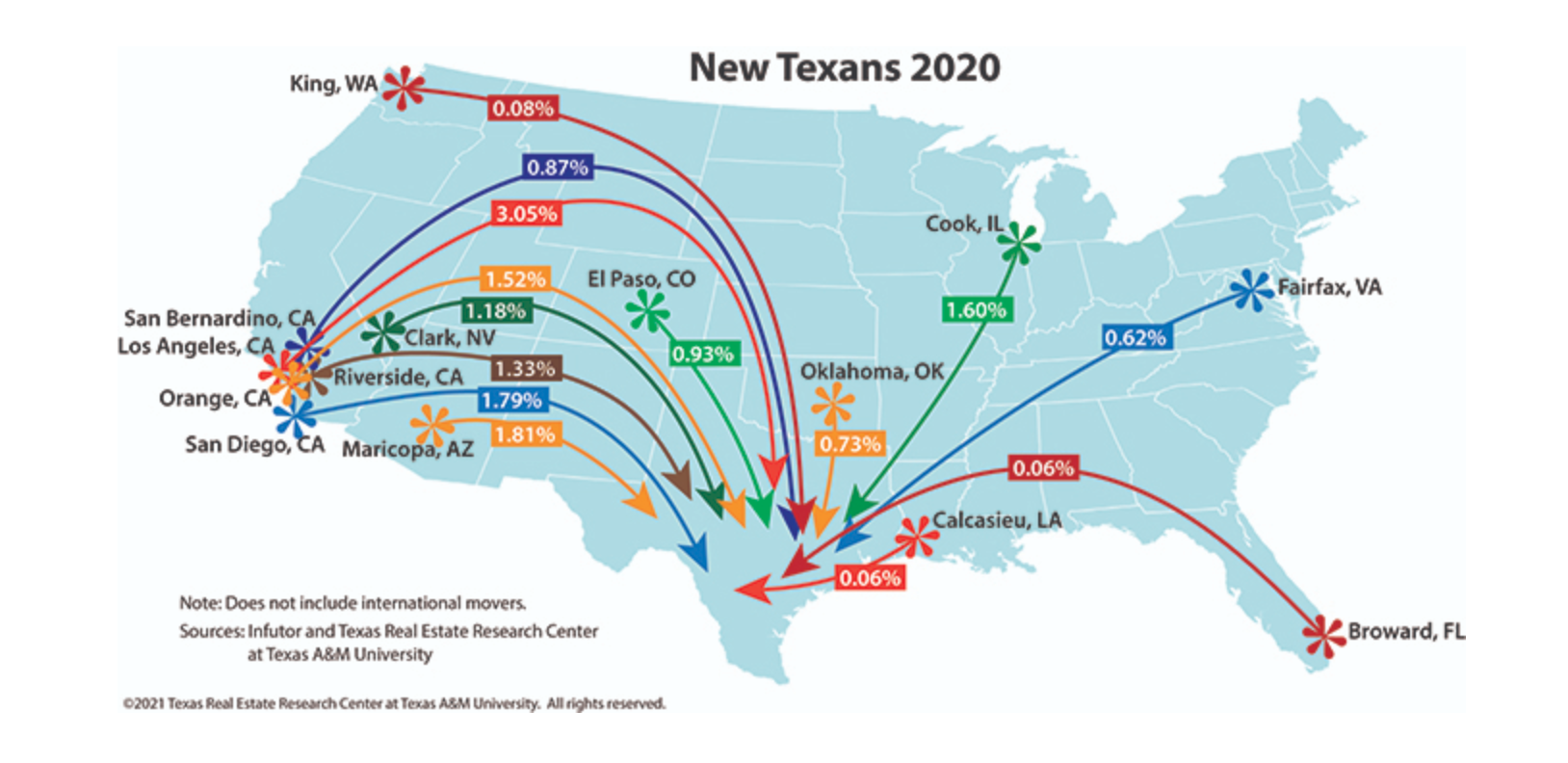

Compared to the rest of the country, Texas is home to “an outsized amount of new homeowners,” and drew more transplants than any other state in 2020. This trend continued in 2021 when half of the top 10 U.S. counties that saw the largest net population gains in 2021 were in Texas. More than one of every ten people moving to Texas in 2020 was from California. Cost of living and high home prices are the primary drivers. This is corroborated by current research by the Bush Institute, which holds that the overall balance of wages and living is much more ideal and highly enticing for California residents who have some of the highest living expenses in the nation.

Besides housing, the labor market is a contributing factor in state migration. Dallas placed first for cities in attracting entrepreneurial talent in tech investment growth in 2020. People are not the only ones heading to Texas; Oracle and Hewlett Packard made the move, Tesla is set to open a new assembly plant, and the Charles Schwab Corp. is among several “Northern California employers” that “have recently shifted thousands of jobs to Texas.” As one California business owner described, there is always “a permit, license, fee, or line to get things done.” However, Texas is more “‘business-friendly offering tax abatements to new businesses.” Texas does not have income tax which makes it an attractive place to live and do business alike.

Many Texas residents benefit from venture capital operations and increasing labor market opportunities. At the same time, as more individuals move to the state, they risk pricing out current residents. As Bill Fulton explains, “The consequences it does have is the people who already live in Texas who maybe do not have a lot of home equity and are not used to those California home prices, they may have a more difficult time buying a house, at least the house they want to buy in the place they want to buy.”

Arizona

In 2019, interstate moves accounted for more than two-thirds of all household growth in Arizona. The Phoenix metro area has one of the highest share of out-of-state newcomers who become homeowners (41%). The majority of domestic migrants come from California, attracted to the lower cost of living and home prices. In 2022, the cost of living in Tucson was about 4% above the national average, with Phoenix at 4% above.

Investors have been taking advantage of Arizona’s popularity. According to the Wall Street Journal, “Big investors now own more than 22,000 rental houses in metro Phoenix, and deploy house-hunting algorithms sophisticated enough to spot a sunny kitchen in a good school district faster than a for-sale sign can be pounded into the yard.” Companies, such as Opendoor, are capitalizing on the population influx and are bringing “Wall Street-style efficiencies and Silicon Valley software to the housing business,” making it even easier for newcomers. In 2022, the effects of these investments are palpable, the housing market prices have increased by 40% since 2020. The national average is 25%.

Besides a housing hub, Arizona is one of the southwest states also emerging as a factory and manufacturing hub. For example, Intel Corporation is investing $20 billion to expand manufacturing in Arizona, incentivized by tax credit for infrastructure investments that create jobs, allowing manufacturers to deduct energy spending from sales tax bills. The WSJ explains in this podcast episode from June 1, 2020 (5:55-12:45).

Florida

Florida has been attracting new residents for some time now. In 2017, this state had the most domestic in-movers from other states (followed by Texas). In 2019, roughly half of the 96,000 new households in Florida came from interstate moves. The Tampa metro (along with the Phoenix metro, mentioned above), has one of the highest shares of out-of-state newcomers who are homeowners, at 41%.

COVID-19 prompted many out-of-staters to buy homes in Florida, particularly New Yorkers, even though overall population growth slowed to its lowest rate between 2014 and 2020. Florida has had some of the greatest instances of inbound migrations from other states in the past two years. Warm weather and low taxes have historically attracted new residents while rising home prices are beginning to push people out. In 2022, the state of Florida boasts 7 of the top 10 fastest-growing housing prices in the nation according to a report from RedFin. The Miami metro area, for example, has one of the highest percentages (40%) of cost-burdened renter households in the country. In 2020, 53.2% of the state’s renters spent 30% or more of their income on rent, which according to the department of housing and urban development, is cost-burdened.

Conclusion

Plenty of Americans are still moving to states like New York and California, but more people move out than in each year. As we’ve seen with the results of the 2020 and 2021 Census data, small changes over time can make large impacts on the demographics of the nation. Bill Fulton of the Kinder Institute states: “‘We are 10-20 years away from the South and West being truly dominant in American culture and American society.’”

What America is seeing at present is a central pillar of the American system of government: federalism. Different states, and even different municipalities, have different policies. If Americans dislike the policies in their current district or state of residence, they have the ability to vote with their feet by relocating and joining millions of others in state-to-state migration.

Thought Leaders/Additional Resources

Flowing Data: Where Americans Live

See Migration History for individual states, 1850-2017, from the University of Washington

See migration patterns for individual counties, from the Census Bureau

American Enterprise Institute: Top Inbound and Outbound States

NerdWallet: U.S. Migration & Housing Affordability Analysis

Tax Foundation: State Migration Trends & 2021 State Business Tax Climate Index

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Find out what your state and district are doing about inbound or outbound migration.

- Do you know the rate of inbound or outbound migration in your community or state? Or the state of the real estate market?

- What are your state’s policies, such as those regarding taxation? How are individuals taxed on their income? What is the sales tax in your state? How are businesses taxed in your state? How do your energy costs compare?

- Is there a task force or project in your community to welcome new residents, or does one need to be formed?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Are there community organizations that attend to the community’s new residents?

- What steps have your state’s or community’s elected and appointed officials taken?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with community organizations, school boards, or local businesses

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, communications@thepolicycircle.org, for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policy makers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Talk to your neighbors or other community members.

- Have they considered moving? Have you considered moving? If so, why?

- Are there any newcomers in your community? Where did they move from, and why did they move?

- See what’s happening to housing inventory and property listing prices in your community.

- See how many households moved in or out of your county.

- Engage with your local elected officials; what is being done to welcome newcomers to the community?

- Engage with your local chamber of commerce. What is the state of the business sector, and what is attracting or discouraging business formation?

- See whether your state lost or gained seats after the 2020 Census, and history of apportionment, to understand population patterns in your state.

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.