Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

What is socialism? Does everyone have the same understanding?

Hear from Dr. Emily Chamlee-Wright, President and CEO of the Institute for Human Studies, on the history of socialism; from Priya Brannick, Senior Fellow for the Commonwealth Foundation for Public Policy Alternatives, on the impacts on labor and education; and from Illinois Circle Leader Ilana Gordon on her personal experiences growing up in Estonia:

Socialism is now associated with Venezuela, Russia, China, the Scandinavian countries, and is even gaining traction in the U.S. political scene. The governments, societies, and economies in each of these nations present very differently, and yet are all described by the same word.

The History Channel explains how views of socialism in the U.S. have changed over time (6 min):

Why it Matters

As citizens of the United States, we have a responsibility to be aware of economic and government systems, so we can understand how they function and the outcomes they produce. This knowledge provides the foundation on which to base our decisions to support or oppose certain reforms, policies, or candidates. What is clear is that there is no clear understanding of what socialism is, what democratic socialism is, or how they relate to capitalism. Confusion and disagreements lie in vague, broad definitions and misunderstandings. Clarifying what socialism is, and what different people mean when they talk about socialism, sheds light on the challenges people across the country are facing. Only with an accurate picture of the present can we determine the policies that will benefit all Americans as we move forward.

What is Socialism

Merriam-Webster defines socialism as “any of various economic and political theories advocating collective or governmental ownership and administration of the means of production and distribution of goods.” The fact that there are “various” forms automatically makes the issue convoluted, but in general the focus is on ownership of economic resources.

Socialism envisions collective ownership, which involves putting workers in control of the means of production and the allocation of economic resources. Yet “it is not at all obvious how meaningful control over something as massive and complex as a modern economy might be shared across tens or even hundreds of millions of people.” The result is nationalization, or state control (as opposed to private ownership by companies and corporations) under the democratic premise that through exercising their vote “the people are themselves in control of the state.”

Government and the Economy

State control, or centralized planning, means the government determines how best to use and distribute economic resources across society. The government is in charge of major industries – electricity, oil, communications, health, and agriculture, for example – and plays a substantial role in determining people’s income and employment, the goods and services available to consumers, and how much those goods and services cost. Even under the so-called “new socialism” that does not seek to abolish private property or redistribute wealth but instead focuses on regulation for public benefit and taxation to reduce inequality, the role of the government is greatly expanded.

Marxists originally described socialism as a kind of stepping stone on the way to communism, defined as a “classless society.” Socialist systems involve a high level of government intervention in the market; communist systems involve complete government control of the economic resources, and provides citizens with all basic necessities, including food, housing, medical care, and education.

NowThisWorld breaks down the subtle difference between socialism and communism (4 min):

Socialist/communist systems are usually contrasted with capitalist/free enterprise systems, in which there is “private ownership of the means of production, where investment is governed by private decisions and where prices, production, and the distribution of goods and services are determined mainly by competition in a free market.” The government’s role is to allow individuals to make the most of their economic freedom. This involves defining and enforcing the rules of society, such as protecting people’s right to own property, and settling disputes that result from conflicting interpretations of the rules.

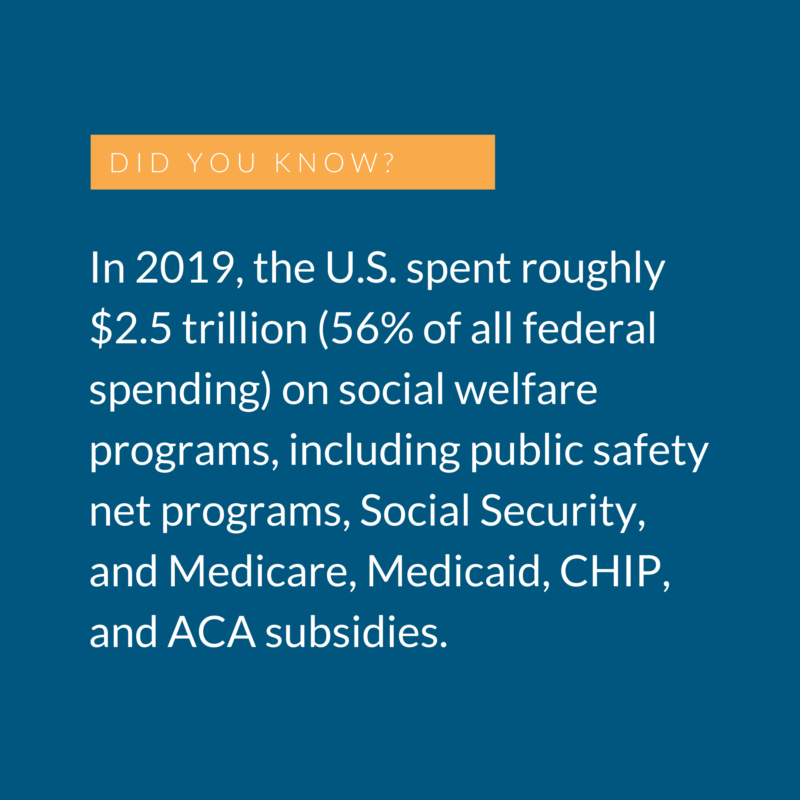

Today, there are no economies that are pure, free enterprise systems. Most are instead considered mixed economies, which involve “a complex mix of ‘capitalist’ market institutions and ‘socialist’ regulatory and redistributive institutions.” The government may step in to handle the “free-rider problem,” meaning it provides certain public goods and services the market would have trouble producing or maintaining on its own, such as national defense. E.J. Dionne and William Galston of Brookings Institution explain:

“There has always been a gap between rhetoric and reality in discussions of (and, especially, attacks on) socialism. Not one economically advanced society can be described as purely capitalist; every one of them is a mixed economy that includes some elements of socialism. Medicare and Social Security are, in a sense, socialist, and so are our public schools and universities, our community colleges, our water supplies and sewers, and our mass transit systems. Municipally owned and built sports stadiums are forms of socialism. North Dakota still has a publicly-owned bank, created during the years when agrarian populism and socialism overlapped. The Tennessee Valley Authority is a form of socialism.”

For more on the basics of free enterprise systems, see The Policy Circle’s Free Enterprise & Economic Freedom Brief.

History

The term “socialism” dates back to the early 19th century and was generally used to refer to a “system of social organization in which private property and the distribution of income are subject to social control.” The term gained popularity in the mid-1800s after the publication of The Communist Manifesto (1848), in which German political philosopher and economist Karl Marx describes the struggle between the working class (proletariat) and the capital class (bourgeoisie) that emerged during the Industrial Revolution. Marx argued that the capitalist motive of profit harmed workers: “Factory owners exploited workers… by subjecting them to debilitating working conditions and exhausting hours.” Socialism arose as a response to these economic and social changes, meant “to remedy the economic and moral defects of capitalism.”

The term “socialism” dates back to the early 19th century and was generally used to refer to a “system of social organization in which private property and the distribution of income are subject to social control.” The term gained popularity in the mid-1800s after the publication of The Communist Manifesto (1848), in which German political philosopher and economist Karl Marx describes the struggle between the working class (proletariat) and the capital class (bourgeoisie) that emerged during the Industrial Revolution. Marx argued that the capitalist motive of profit harmed workers: “Factory owners exploited workers… by subjecting them to debilitating working conditions and exhausting hours.” Socialism arose as a response to these economic and social changes, meant “to remedy the economic and moral defects of capitalism.”

Socialism gained momentum in the early 1900s, even in the U.S., where socialist governors held offices in over 300 cities. In the 1912 presidential election, socialist candidate Eugene V. Debs earned 6% of the popular vote. Socialism’s role in electoral politics shrunk substantially in the U.S. after the first World War, when “Communist seizure of power in what became the Soviet Union” contributed to the first Red Scare in the U.S.

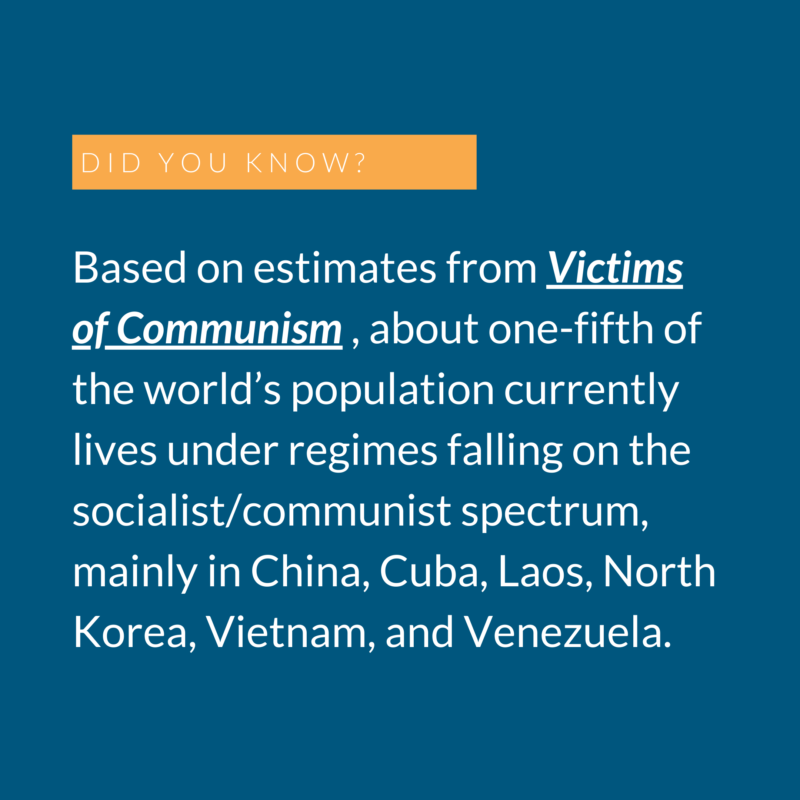

During the early- to mid-20th century, one-third of the world’s population lived under socialist/communist regimes, most notably China under Mao Zedong and the U.S.S.R. under Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin. In these cases, “the state, through a single authoritarian party, controlled a society’s economic and social activities with the goal of realizing Marx’s theories.”

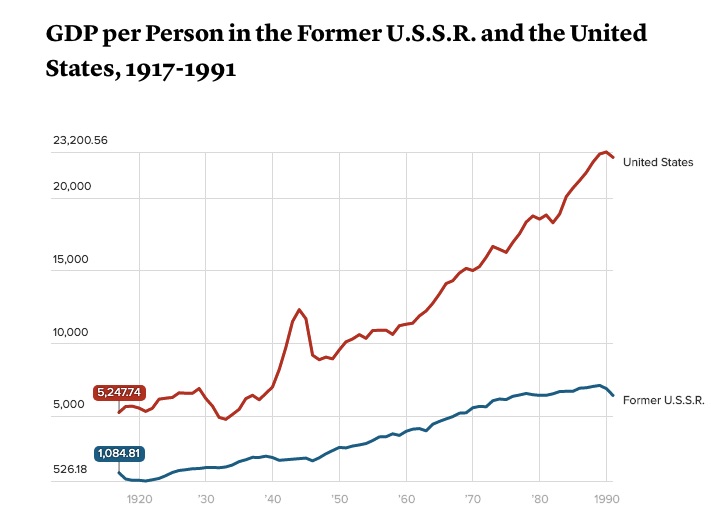

Realizing Marx’s theories did not result as intended: Economic life in the U.S.S.R. “rapidly became so disorganized that within four years of the 1917 revolution, Soviet production had fallen to 14% of its pre revolutionary level. By 1921, Lenin was forced to institute the New Economic Policy (NEP), a partial return to the market incentives of capitalism.” Meanwhile, the gap in living standards between London and Beijing expanded from 2:1 in the 18th century to 6:1 in the 20th century when the U.K. saw the benefits of free trade while China lived under socialism.

In Europe, socialism was still present in electoral politics, but parties distanced themselves from the policies of the U.S.S.R. and China. The socialist parties in the U.K. and Germany that had been calling for nationalization changed the discourse to emphasize individual freedoms and private property, admitting that “every concentration of economic power, even in the hands of the state, harbors danger.” By the 1970s, the focus on “using government to improve the lives of all citizens” rather than on government control of the economy marked a shift in socialist philosophy and set the foundation for “the system of ‘social democracy.’”

Since the 2008 global financial crisis, many Americans have been concerned by rising inequality, slowed economic growth, and declines in upward mobility. According to Kimberly Phillips-Fein, associate professor of history at NYU, “People historically have organized as socialists when they want to express the idea that they object to something in the operation of capitalism as a system.” The concern that many Americans are being left behind even as the economy recovers has elicited “an intensifying critique of how contemporary capitalism works” and “has brought socialism back into the mainstream.”

Understanding Socialism

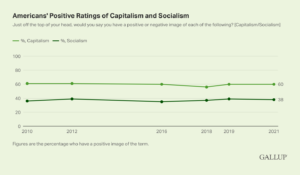

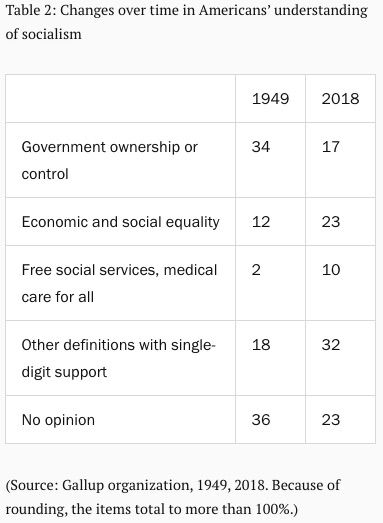

Americans’ feelings toward socialism have been largely stable over the past decade, with just under 40% of Americans rating socialism positively. A similar survey from PEW Research in 2019 found 55% of respondents had a negative opinion of socialism, and a 2019 Monmouth poll found 57% of Americans “believe socialism is not compatible with American values. In a 2021 Gallup poll, “socialism” tied with “federal government” as the lowest rated of six terms, with only 38% of respondents saying they have a positive image of either.

Another Gallup poll from late 2018 demonstrates most respondents do not define socialism as government control; about a quarter of respondents associate socialism with social equality, and only 17% associate it with government control. Almost one-third of respondents chose “other definitions with single-digit support,” illustrating a clear lack of consensus of the term, and a stark difference in understanding since the first poll in 1949. In fact, the 2021 Gallup poll revealed that of the 38% of Americans who are favorable towards socialism, just over half are also favorable towards capitalism (meaning only 17% of Americans embrace socialism and are critical of capitalism).

Not all references to socialism have been the same throughout history, adding to the confusion. In Germany during the 1930s and 1940s, “Nazi” was the name given to the National Socialism party. Meanwhile, President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal policies were both lauded and criticized for being socialist. Today, socialism is associated with countries with radically different social, economic, and political outcomes. Countries including Zimbabwe, Nicaragua, and Venezuela are common examples of how socialism can go wrong. In comparison, Bolivia embraces the socialist label but in reality has not entirely shunned the free market, and has seen steady economic growth along with a decline in poverty since the early 2000s. In Venezuela, opposition leader Juan Guaidó claims, “What they refer to as socialist in the United States is what we’d call a Social Democrat here.”

Not all references to socialism have been the same throughout history, adding to the confusion. In Germany during the 1930s and 1940s, “Nazi” was the name given to the National Socialism party. Meanwhile, President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal policies were both lauded and criticized for being socialist. Today, socialism is associated with countries with radically different social, economic, and political outcomes. Countries including Zimbabwe, Nicaragua, and Venezuela are common examples of how socialism can go wrong. In comparison, Bolivia embraces the socialist label but in reality has not entirely shunned the free market, and has seen steady economic growth along with a decline in poverty since the early 2000s. In Venezuela, opposition leader Juan Guaidó claims, “What they refer to as socialist in the United States is what we’d call a Social Democrat here.”

E.J. Dionne and William Galston of Brookings Institution note, “the impulse to use public power to smooth the market economy’s rough edges and to enhance opportunity and security for all Americans is a powerful current in today’s post-Great Recession politics” as many criticize the status quo and “call the fundamentals of our economic system into question.”

Democratic Socialism

After World War II, “Americans viewed socialism through the prism of Soviet communism. Today, they view it through the prism of the welfare state.” Under democratic socialism, individuals, companies, and corporations own the means of production, but there is a larger role for government in the form of “taxation, government spending, and regulation of the private sector.” The taxation and government spending is supposed to fuel policies to “help provide for people’s most basic needs and help all people have an equal chance at achieving success.”

Democratic socialists also “believe strongly in democracy and democratic principles…they don’t feel socialism should be forced on people, but they are fundamentally anti-capitalist and believe the government should urge privately owned businesses toward granting workers as much control as possible.” There was a similar difference between the Western socialist parties of the mid-twentieth century and Soviet-style communism: while one was “undemocratic and totalitarian” the other “was willing to submit to the electorate’s democratic verdict” and opposed the use of force to achieve policy goals.

It should be noted that a democratic vote is not an automatic safeguard; Hugo Chavez was fairly elected as Venezuela’s president in 1998 with 56% of the vote, but power and coercion still found their way into play.

The Myth of Scandinavian Socialism

Those who have embraced socialism in the U.S. use the Scandinavian countries as examples of success, but the leaders of these countries dispute the myth of Scandinavian socialism. According to Denmark’s Prime Minister, “The Nordic model is an expanded welfare state which provides a high level of security for its citizens, but it is also a successful market economy with as much freedom to pursue your dreams and live your life as you wish.”

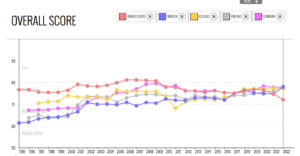

Based on GDP per capita, Sweden was the fourth-richest member of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in 1970. By 1998, it had fallen to sixteenth after expanding its welfare state and raising taxes on corporations and businesses. Companies moved to other countries to escape the tax burden. Sweden’s decision to lower taxes, deregulate financial markets, and return state-owned companies to private ownership restarted its economic growth and has since fueled its successful public sector. Today, Sweden has:

- No occupational licensing or minimum wage laws

- Low corporate tax rates

- Almost no property taxes

- A school voucher system

- A pension system based on defined contributions

Swedish historian Jonah Norberg explains how Sweden’s success comes from free markets (5 min):

Watch the full PBS documentary, Sweden: Lessons for America, here.

In The Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden actually all score higher than the U.S. in terms of security of property rights and trade freedom, and score similarly in terms of business freedom, investment freedom, and overall economic freedom. These countries “are in many ways more market-oriented [than] the United States.” In the Tax Foundation’s International Tax Competitiveness Index of 36 OECD countries, Finland ranks 7th, Sweden ranks 9th, Norway ranks 11th, Iceland ranks 13th, Denmark ranks 16th, and the U.S. ranks 20th in terms of how competitive these countries’ corporate tax rates are, which reflects how attractive these countries are to businesses and business investments. See The Policy Circle’s Taxes Brief for more on corporate taxes, and how other taxes affect economic growth and competitiveness.

Socialism in Practice

Problems for Innovation and Entrepreneurship

In principle, socialism’s “strict limits on private enterprise limited accumulation of wealth and supposedly provided for a relatively high degree of income equality.” In practice, socialist countries that achieved income equality were on the whole poorer than more economically free countries.

Socialism operates under the assumption that wealth is a limited resource that needs to be evenly distributed. Economic growth, however, is indicative of wealth not being a zero-sum game. Without private enterprise to generate revenue and create wealth, socialist countries experienced much lower economic growth in comparison with countries with more free market competition in the private sector. Inequality between the governing class and the governed was also prevalent.

Problems with Central Planning

Problems with Central Planning

Under socialism, central planning “experts” determine how to use and distribute economic resources, which means they also set the funding conditions, regulations, and requirements that steer the behaviors of individuals, businesses, institutions and communities. This method disregards supply and demand, and fails to align economic incentives to innovate, produce, and distribute goods and services. Economist Ludwig von Mises argued “that a socialist government could not make the economic calculations required to organize a complex economy efficiently.” There would be no way for a centralized planner to acquire the supply and demand information necessary for optimal production and distribution. Economist Russ Roberts illustrates what this looks like with a daily staple: Bread (6 min):

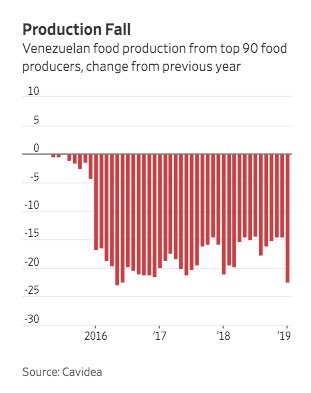

Agriculture is one sector that socialist governments have repeatedly attempted to control, as was seen in the early-mid 1900s in the USSR, China, and Cuba, and more recently in Venezuela. During these socialist takeovers, citizens were required to work the land and output belonged to the state, and government employees with little specialized knowledge were left to make all the production and distribution decisions. Chapter 8 of the Economic Report of the President details the catastrophic results of drastic food shortages and tens of millions of people dying of starvation:

Agriculture is one sector that socialist governments have repeatedly attempted to control, as was seen in the early-mid 1900s in the USSR, China, and Cuba, and more recently in Venezuela. During these socialist takeovers, citizens were required to work the land and output belonged to the state, and government employees with little specialized knowledge were left to make all the production and distribution decisions. Chapter 8 of the Economic Report of the President details the catastrophic results of drastic food shortages and tens of millions of people dying of starvation:

- In the U.S.S.R., the population of livestock fell drastically, by 75% for cattle and almost 50% for horses, between 1928 and 1932. The population faced famine between 1932 and 1933.

- After China’s Great Leap Forward began in 1958, production of grain and meat fell by 21% and 55%, respectively, resulting in a famine between 1959 and 1961.

- Between 1959 and 1963, 70% of Cuba’s farmland was nationalized and all livestock and crop production fell. Production of sugar, the island nation’s biggest crop, dropped by one-third.

- In Venezuela, domestic food production has plummeted since nationalizing the agricultural industry between 2005 and 2010, as illustrated in the chart. The government provides all materials from seeds to fertilizer to machinery, but farmers report they do not receive supplies. According to Venezuela’s Confederation of Associations of Agricultural Producers, the country went from producing 70% of its food to importing 70% of its food. For more on Venezuela’s troubles and the role socialist policies played, see The Policy Circle’s Deep Dive on Venezuela.

There is even evidence of central planning problems in the U.S. on Native American reservations. In Robert Miller’s Reservation Capitalism, he cites a report that estimates the federal government spends $9.51 per acre when managing tribal lands. When tribes manage their own natural resources, the federal government only contributes an average of $2.58 per acre, because tribal managers make profits, create jobs and economic development, and sustainably preserve ecosystems. When the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes (CSKT) took control of forest management on the Flathead Reservation in Montana, they “earned more than $2 for every $1 spent compared to the U.S. Forest Service just breaking even,” and “timber quality, wildlife habitat, and water quality were all better under tribal management.”

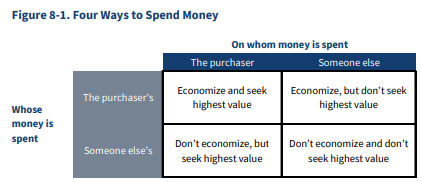

Spending & Prices

Along with creating supply issues, central planning skews prices, as depicted in Figure 8-1 from Chapter 8 of the Economic Report of the President. Consumers tend to be careful when they spend their own money, but are likely to be more discerning of a product’s value when spending on themselves (upper left) than when spending on someone else (upper right). When a consumer spends someone else’s money on themselves, they still seek the best value but are less careful with how much they are spending (lower left). When neither the recipient of the spending nor the owner of the money are involved in the transaction, the picture is different. If the government (or other third party) spends government revenue (taxpayer money) on government program beneficiaries, there is little incentive to find the most economical option or the option of highest value (bottom right). In extreme cases where the government gives products to citizens for free, such as with Venezuela’s handouts of everything from food to refrigerators, “then something other than a willingness to pay the market price” will determine the value and who receives the available supply. It could be a government eligibility formula, or a willingness to wait in line. In either case, the market value is skewed and does not reflect the actual price of goods and what went into making them.

Pricing and profits are not just about money; both measure how well a product or service meets a need. When businesses compete to supply products and services, producers are encouraged to innovate and find better or less expensive ways to produce. When the government steps in as the supplier, it crowds out independent businesses. This results in a loss of economic opportunity for the employers and employees who would otherwise earn a living by providing needed products and services.

Understanding Capitalism

“Capitalism refers to an economic system in which a society’s means of production are held by private individuals or organizations, not the government, and where products, prices, and the distribution of goods are determined mainly by competition in a free market.” Globally, 56% of respondents to the January 2020 Edelman Trust Barometer believe “capitalism as it exists today does more harm than good in the world.”

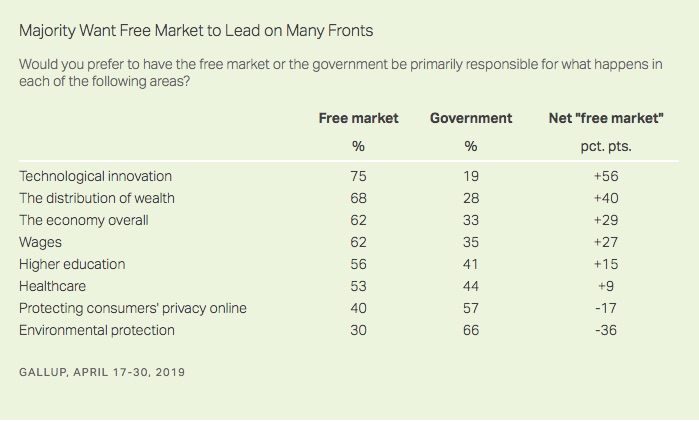

In America, when asked about free market principles, more than half of respondents in an April 2019 Gallup poll said they favored the free market over government control in areas of healthcare, higher education, wages, technological innovation, distribution of wealth, and the overall economy.

These opinions have mostly held steady. In a 2021 Gallup poll, Americans were most positive towards the terms “small business” (97% positive), “free enterprise” (84% positive), and “capitalism” (60% positive).

Shareholder & Crony Capitalism

Many young Americans associate capitalism with the brutal economic recession from 2007-2009. Linking capitalism to greed and inequality is “thinking of a specific form of capitalism that deems the sole purpose of companies is to increase stock prices and enrich investors,” often referred as shareholder capitalism. Compared to positive feelings towards small business and free enterprise, only 46% of Americans reacted positively to the term “big business” in the 2021 Gallup poll.

According to the Discovery Institute’s Christopher Rufo, this thinking is why “Boeing and the airlines spent billions on stock buybacks, but didn’t think to prepare for the next financial crisis.” In 2019, the Business Roundtable released a new outline of “a modern standard for corporate responsibility” that commits to all stakeholders – customers, communities, suppliers, employees, and shareholders.

Others argue that a significant portion of shareholders are “retirees who count on shareholder returns for income from their pensions, 401(k)s, individual retirement accounts, mutual funds, annuities and death benefits.” Additionally, “[m]aximizing long-term shareholder value requires companies to make sure that employees and suppliers are in a strong position to make the business successful” by investing in employees and maintaining good relations with the community and customers.

Another issue area is crony capitalism, “where big business and government work together for their own interests through systems of reciprocal favors.” Agricultural subsidies to the sugar industry, the monopoly of the taxi industry, and even the distribution of funds in the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act have all been cited as examples. Professor Chris Coyne of George Mason University explains crony capitalism in terms of the Occupy Wall Street movement (3 min):

Alexandra Ocasio Cortez claims capitalism “means that we seek and prioritize profit and the accumulation of money above all else, and we seek it at any human and environmental cost.” Such definitions of shareholder and crony capitalism rarely refer to the market-oriented capitalism that allows entrepreneurs to use their skills, passions, and creativity to create something of value for others, make a living for themselves, and drive the wealth and prosperity of America. Andy Pudzer explains this view (3 min):

Fostering Entrepreneurship

Cornell professor and American Enterprise Institute visiting scholar R. Richard Geddes says the rules and regulations that democratic socialism embraces as a solution to crony capitalism can also hurt entrepreneurship by hampering private property rights, making it more difficult for entrepreneurs to grow their business, or discouraging entrepreneurship in the first place. In one survey from 2017, for example, over 40% of small business owners indicated “they had delayed or halted business investments” because of already existing regulatory costs and complexities. Similarly, entrepreneurs in the European Union say they are stifled by the need to “navigate onerous tax rates and restrictions.” In 2018, 49% of venture capitalists and founders said European regulations make them hesitant to invest. This makes it more difficult for startups to get off the ground, generate a profit, and spur economic growth, which is why Europe’s technology sectors have struggled on the global stage.

Cornell professor and American Enterprise Institute visiting scholar R. Richard Geddes says the rules and regulations that democratic socialism embraces as a solution to crony capitalism can also hurt entrepreneurship by hampering private property rights, making it more difficult for entrepreneurs to grow their business, or discouraging entrepreneurship in the first place. In one survey from 2017, for example, over 40% of small business owners indicated “they had delayed or halted business investments” because of already existing regulatory costs and complexities. Similarly, entrepreneurs in the European Union say they are stifled by the need to “navigate onerous tax rates and restrictions.” In 2018, 49% of venture capitalists and founders said European regulations make them hesitant to invest. This makes it more difficult for startups to get off the ground, generate a profit, and spur economic growth, which is why Europe’s technology sectors have struggled on the global stage.

Learn Liberty explains further how cronyism is hurting the economy, but why adding rules and regulations may not be the solution (3 min):

The Policy Circle’s Government Regulations Brief looks more closely at regulations and economic opportunities.

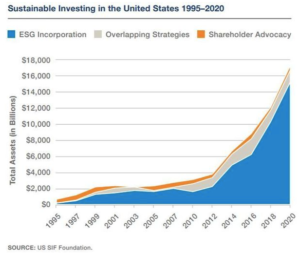

Capital Investments & Market Demand

Capital investments are necessary to turn an idea into a product or service, or expand a business plan to meet growing demand. The market responds to this kind of demand in a manner that central planning and excessive business restrictions cannot. In 2010, portfolio managers held $2.5 trillion in U.S. assets using environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria to guide their investments. Less than 20% of companies on the S&P 500 index published sustainability or corporate responsibility reports. By 2021, 92% of S&P 500 companies published these reports, and portfolio managers hold about $15 trillion in assets based on ESG criteria.

These changes demonstrate a market shift as investors put more money behind businesses that behave sustainably. Instead of regulations, market demand fuels support for a system “in which companies value communities, the environment and workers just as much as profits.”

Without overburdensome regulations, entrepreneurs have the economic opportunity to turn an idea into a successful small business that creates jobs, provides a needed product or service for the population, and generates economic growth. Free the People’s Matt Kibbe discusses economic and social freedom and liberty in the context of capitalism, socialism, and the supposed spectrum of -isms, considering where we are now and the path forward (9 min).

Conclusion

Using the same term to describe the former Soviet Union, Venezuela, and the Scandinavian nations demonstrates a misunderstanding of socialism, and a misunderstanding of its apparent rise in popularity in recent years. At the same time, to denounce the evils of capitalism by tweeting on an iPhone demonstrates a misunderstanding of free market systems. As citizens, we have a responsibility to ourselves and each other to familiarize ourselves with systems of government, economics, and world history, so we do not repeat the mistakes of the past. As F.A. Hayek once said, “‘We must make the building of a free society once more an intellectual adventure, a deed of courage.'” Misunderstandings only expand political divisions; informed discussions are what can set us on the path forward towards the goal of human flourishing.

Using the same term to describe the former Soviet Union, Venezuela, and the Scandinavian nations demonstrates a misunderstanding of socialism, and a misunderstanding of its apparent rise in popularity in recent years. At the same time, to denounce the evils of capitalism by tweeting on an iPhone demonstrates a misunderstanding of free market systems. As citizens, we have a responsibility to ourselves and each other to familiarize ourselves with systems of government, economics, and world history, so we do not repeat the mistakes of the past. As F.A. Hayek once said, “‘We must make the building of a free society once more an intellectual adventure, a deed of courage.'” Misunderstandings only expand political divisions; informed discussions are what can set us on the path forward towards the goal of human flourishing.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

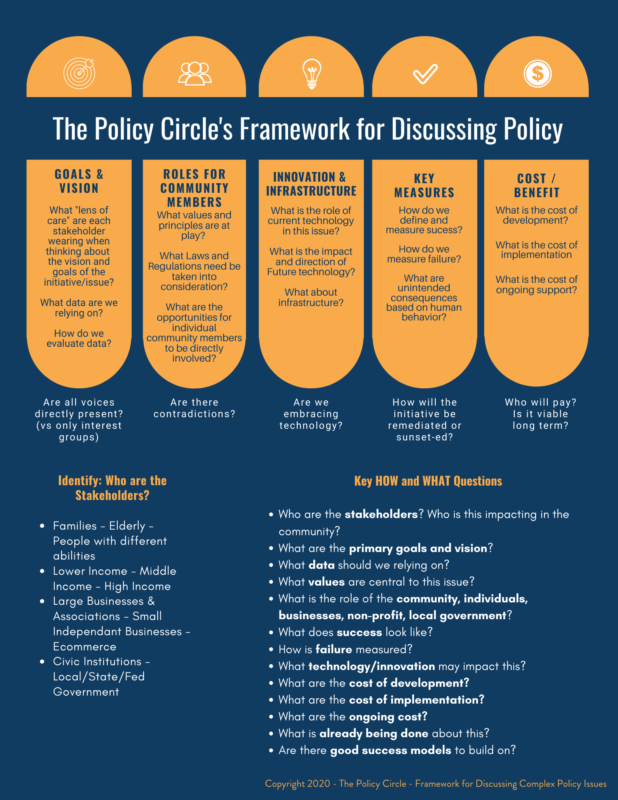

Be thoughtful about how the economy works and how humans interact with each other through the economy. When evaluating social and economic policies that will impact your life, consider The Policy Circle’s Framework for Discussing Policy:

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.

Deep Dives

Want to dive deeper on Socialism? Consider exploring the following: