Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

Case Study

In the spring of 2019, the FBI charged fifty people across six states – including well-known celebrities and business leaders – “with committing fraud to get their children into selective colleges.” College athletic coaches and university administrators were accused of accepting millions of dollars in bribes to help admit students as recruited athletes, and standardized test proctors were accused of facilitating cheating and falsifying scores.

Known as “Operation Varsity Blues,” the case brings up important questions regarding college admissions practices and the belief that a quality college education depends on attending an elite school. On the American Enterprise Institute’s education podcast, Report Card, host Nat Malkus discusses the implications with Richard Reeves and Frank Neville.

Why it Matters

Higher education “creates lifelong opportunities that promote economic success, political participation, and other benefits,” such as bolstering economic competition within and across states. These benefits provide overall gains for society as a whole. Additionally, according to Bryan Caplan, author of The Case Against Education, “‘there is no known college major where the average earnings are not noticeably higher than just an average high-school graduate.’” So, it still seems to pay to go to college on an individual level as well.

But the existing system is not working well for many, as costs have been rising rapidly. A college education is simply out of reach for many based on the price, and for others it can mean thousands of dollars of debt. At the same time, stigma surrounds decisions not to pursue a traditional four-year college degree. If individuals’ post-secondary educations create financial burdens for themselves, it hinders the overall societal benefits that higher education can provide.

Putting it in Context

History

The first colonial colleges in the U.S. – Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Columbia, Brown, Rutgers, Dartmouth, and the College of William and Mary – were established in the early 1600s. These schools were almost exclusively for ministry, medicine, and law, but adopted “‘practical subjects’” like agriculture and engineering during the 19th century.

The Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1890 granted land to each state. The land could be sold so that the proceeds could be invested to found a public college. Such public schools were dubbed land-grant colleges and universities. Meanwhile, religious organizations and private benefactors were also building smaller, private universities. The 20th century saw the continued development of state-wide systems of public colleges and universities, and the continued expansion of smaller, private colleges and universities.

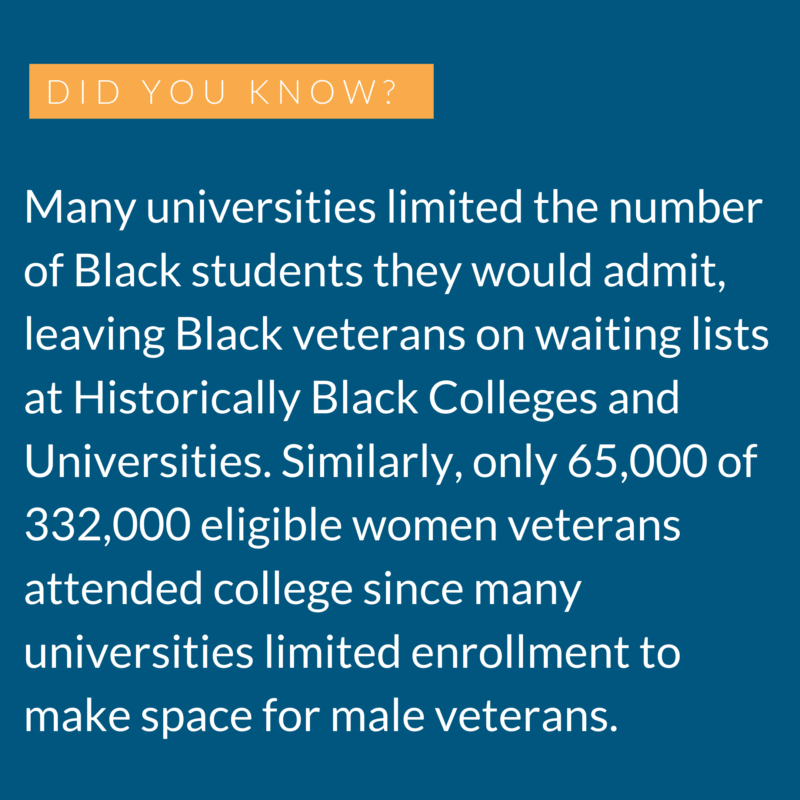

Even with the growing number of institutions, college attendance in the early 20th century was limited to families that “could afford the direct costs of enrollment and the opportunity costs of lost labor and wages.” College was far more accessible after the passage of the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act (also known at the GI Bill) in 1944.

The GI Bill “offered veterans a year of unemployment pay after their homecoming; guaranties for loans to purchase homes, businesses, or farms, and tuition and living stipends for college or vocational programs.” A college education had been reserved for the elite before World War II, but the GI bill sent almost 8 million of 16 million World War II veterans to education or training programs in the decade after the war. The GI Bill cost roughly $14.5 billion, but vets who took advantage of it earned $10,000-$15,000 more per year than those who did not, “generating ten times the cost of the program in tax revenue.”

Still, many credit the GI Bill with “completely reinventing American higher education” by giving significantly more Americans access, which in turn expanded American university instruction and curriculum to include a wider range of career paths. In the second half of the 20th, the 1958 Cold War and National Defense Education Act further opened different avenues of study and “drew students into science, technology, engineering, and mathematics fields.” The Higher Education Act of 1965 also expanded access and established the precedent of the federal government providing funding for low-income students to access higher education.

Still, many credit the GI Bill with “completely reinventing American higher education” by giving significantly more Americans access, which in turn expanded American university instruction and curriculum to include a wider range of career paths. In the second half of the 20th, the 1958 Cold War and National Defense Education Act further opened different avenues of study and “drew students into science, technology, engineering, and mathematics fields.” The Higher Education Act of 1965 also expanded access and established the precedent of the federal government providing funding for low-income students to access higher education.

By the Numbers

Institutions

The National Center for Education Statistics reports there are over 4,300 degree-granting post-secondary institutions, with roughly 1,500 2-year colleges and about 2,800 4-year colleges. According to U.S. News, over 1,600 are public, just under 1,700 are private nonprofit institutions, and just under 1,000 are for-profit.

Enrollment

In 1975, 51% of high school graduates immediately went to college upon graduation. By 1995 that number had increased to 62% and stood at 69% in 2015. In total, postsecondary enrollment increased by almost 30% between 1975 and 1995, and by another 40% between 1995 and 2015. In fall 2019, there were 16.6 million undergraduate students and 3.1 million graduate students attending postsecondary institutions in the U.S. According to Fall 2021 data from the National Student Clearinghouse Research Center, undergraduate enrollment has fallen 6.5% since 2019, graduate enrollment has risen 5.3%, and total post-secondary enrollment declined by 4.6%.

A significant portion of incoming college students are not recent high school graduates; almost half are over age 25 when they first enroll. Additionally, roughly 25% are parents, over 60% hold full- or part-time jobs, and 38% are enrolled part-time. As of 2019, 14% of students enrolled in college were attending a completely online college.

The total percentage of U.S. adults ages 25 or older who have completed a bachelor’s degree or higher increased from 29.9% in 2010 to 36% in 2019. For the 12th year in a row in 2020, women earned a majority of advanced degrees.

Costs

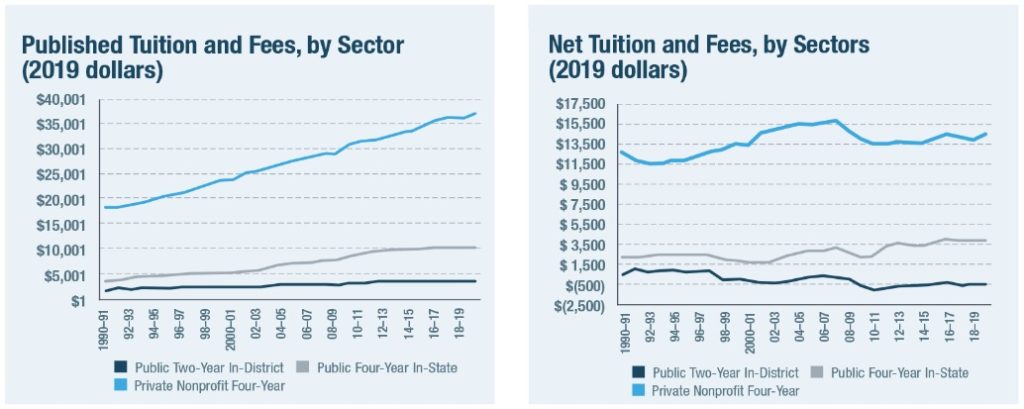

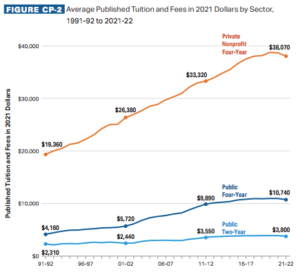

While educational levels of attainment have risen, costs have skyrocketed as well. According to the CollegeBoard’s 2019 report the average published tuition and fees has more than doubled for private, nonprofit four-year institutions and for public two year institutions between 1989 and 2019. For public four-year institutions over that same time period, tuitions and fees have almost tripled. As costs continue their upward trends, experts cite a number of factors ranging from administrative costs to less state funding. We dive into this further below.

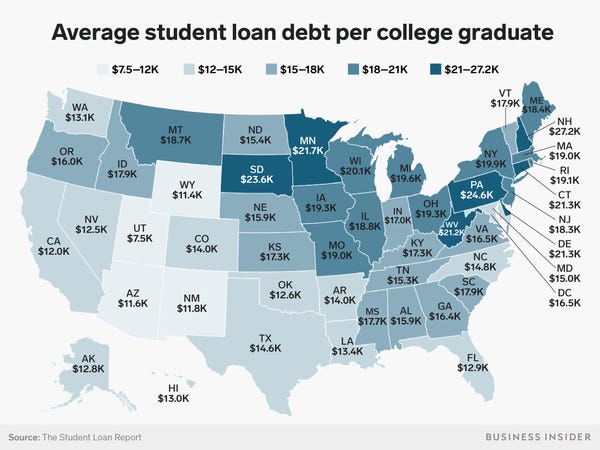

Looking at costs, it is no surprise that student debt is the second largest type of debt held by Americans (after mortgages). Total student loan debt has tripled since 2007; in 2000, 50% of students took out loans, with the average amount of $16,500. By 2012, 60% of students were taking out loans, with the average of $20,400. As of January 2022, roughly 43.4 million Americans owed $1.75 trillion in student loans. This places the average debt per student at over $40,000.

See this interactive map of student debt. For more on the implications of student debt, and other kinds of debt, see The Policy Circle’s Financial Literacy Brief.

The Role of Government

Federal

As mentioned above, federal involvement in higher education started in the 19th century with the Morrill Acts. This has only increased since the GI Bill and the Higher Education Act of 1965, and stands in contrast to the federal government’s role in primary and secondary education. For more on those differences, see The Policy Circles’s K-12 Education Brief.

During the 2015-2016 school year, the federal government distributed $158 billion in financial aid (grants, loans, tax credits, and work-study funds) to undergraduate and graduate students. In fact, the U.S. government is the nation’s largest student lender. Between 2007 and 2018, the dollar amount of federal loans rose by over 25%, and the number of borrowers rose by 14%. In 2018, the federal government lent $94 billion to students. As of the end of 2021, 43.4 million Americans owed $1.61 trillion in federal student loans. The Congressional Budget Office predicts the federal government will originate $1.05 trillion in new loans between 2020 and 2029.

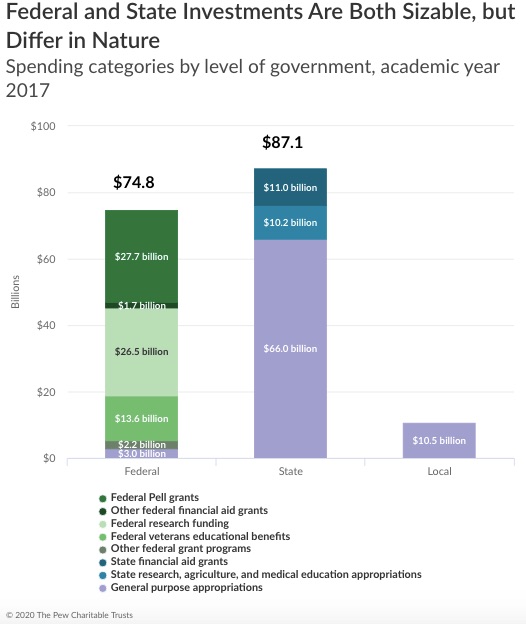

There are three main federal funding streams:

- Pell Grants, roughly $28 billion in 2017, with an additional $1.7 billion for other need-based financial aid grants;

- Federal grants, contracts, and agreements for research, which amounted to $26.5 billion in 2017;

- Veterans benefits, which amounted to $13.6 billion in 2017.

The purpose of financial aid is to increase access to higher education by reducing gaps between high and low income students. Most financial aid programs have a maximum income threshold or require proof of an unmet financial need to determine eligibility. By increasing access, more students have more institutions from which they can choose. Some argue that federal funds allow individual students to choose from a wide range of higher education options, while others say “the federal responsibility for ensuring access to quality higher education across the nation is not being adequately met through this system,” and instead recommend the federal government provide funding directly to states or institutions as incentives for providing high-quality and affordable educational options.

The purpose of financial aid is to increase access to higher education by reducing gaps between high and low income students. Most financial aid programs have a maximum income threshold or require proof of an unmet financial need to determine eligibility. By increasing access, more students have more institutions from which they can choose. Some argue that federal funds allow individual students to choose from a wide range of higher education options, while others say “the federal responsibility for ensuring access to quality higher education across the nation is not being adequately met through this system,” and instead recommend the federal government provide funding directly to states or institutions as incentives for providing high-quality and affordable educational options.

State

While federal funding goes mostly to individual students or university-based research, states pay for general operating expenses of public institutions. In total, federal and state funding accounted for 34% of public institutions’ total revenue in 2017.

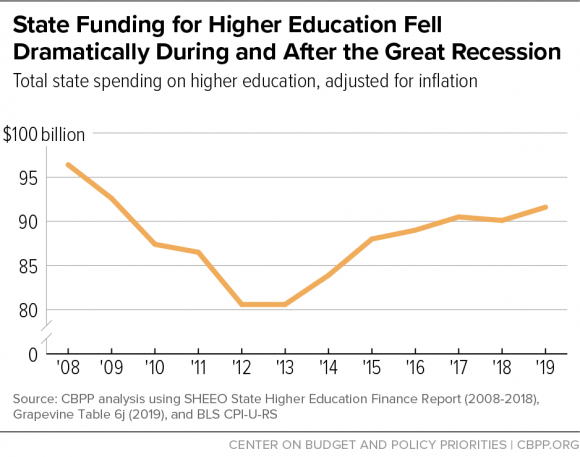

In 1990, state funding per student was 140% higher than federal funding per student. Since the Great Recession, however, state investments have declined and federal investments have increased. While federal funding per student grew by almost 25% between 2000 and 2015, comparable state expenditures fell by over 30%, and state funding is only about 12% more than federal spending.

Still, it’s difficult to make generalizations across the nation as there is no one size fits all solution. In 2015, for example, Colorado, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, and Vermont all spent less than $4,000 per student, while Alaska and Wyoming spent over $14,000 per student. Wisconsin provides more funding per student to public two-year colleges than it does to public four-year colleges. Meanwhile, Arizona community colleges rely on local funds and tuition revenue.

Financial aid also awards the performance of students who maintain certain grade point averages or achieve certain scores on college entrance exams. Far more state aid is offered based on academic performance than federal aid is. While it is a simple formula, it has been criticized for providing funding to students who would have gone to college without the additional financial support. For the 2016-2017 school year, state institutions awarded $11 billion in financial aid, with roughly 25% based on merit.

Financial aid also awards the performance of students who maintain certain grade point averages or achieve certain scores on college entrance exams. Far more state aid is offered based on academic performance than federal aid is. While it is a simple formula, it has been criticized for providing funding to students who would have gone to college without the additional financial support. For the 2016-2017 school year, state institutions awarded $11 billion in financial aid, with roughly 25% based on merit.

For the most part, public two- and four-year colleges rely on state and local appropriations, which made up 54% of funds for teaching in 2018 at these institutions. State-wide systems that have multiple campuses usually operate with state-level coordination, such as a Higher Education Board or Authority. Most institutions have a local Board of Trustees making major decisions.

The Role of the Private Sector

Private institutions are not government run, and for that reason they primarily get their funding from donors, endowments, investments, and tuition. Because the state government is not covering a significant portion of the cost of attendance with taxpayer money, private institutions usually have published tuition and fees that seem much higher than those of public ones. However, private colleges and universities offer merit scholarships and financial aid resources that make the net cost of tuition often comparable to public institutions. Some of the U.S.’s most prestigious institutions, such as the Ivy League schools, are private. Additionally, many schools with religious affiliations are also private.

Khan Academy provides more information on public vs private schools (2 min):

In the private sector of higher education, most institutions are divided into either nonprofit or for-profit. Nonprofit universities usually offer traditional curricula covering sciences, math, and engineering, arts and humanities, and business and finance. Campus life includes sports, student clubs and activities, and Greek life. Students almost always have access to federal aid. For-profit colleges tend to focus more on skills and vocational education, and often do not offer campus amenities because they are typically online. As the name indicates, these schools need to make a certain amount of money to stay open each year.

Challenges and Areas for Reform

The Value of a Diploma

Graduating from college is still the best way to secure a place in the middle class, and those who don’t earn a bachelor’s degree are falling further and further behind their degree-holding peers in terms of education earnings gap. Across all races and ethnicities, post-graduate families “enjoy a clear income advantage over families without at least a bachelor’s degree.” Between 1995 and 2015, the earnings gap between high school graduates and graduates with a bachelor’s degree or higher rose from 72% to 94% for men, and from 88% to 97% for women. Across all demographics, the Census Bureau found that average earnings for those over the age of 25 with a high school diploma were $35,615, compared to average earnings for those with a bachelor’s degree ($65,482) or an advanced degree ($92,525).

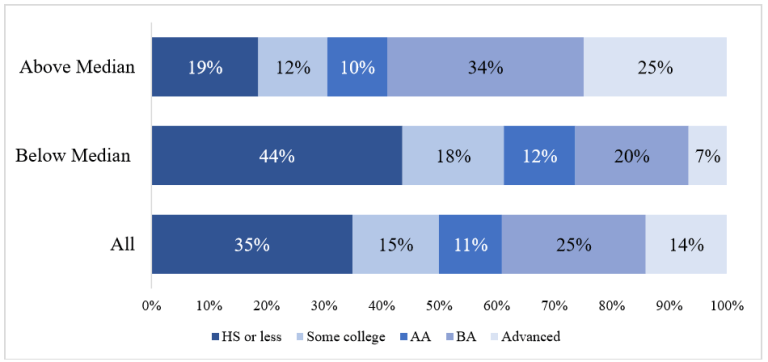

In 2019, 44% of adults with earnings below the median of $47,500 had no education beyond high school, compared with 19% of those with earnings above the median. Over the course of their careers, a college graduate will out-earn a high school graduate by and estimated $1 million.

Beyond earnings, employment rates are higher amongst those with higher levels of education. In 2019, the employment rate for 25-34 year olds with a postsecondary degree was 87%. For 25-34 year olds with some college it was 80% and for those with a high school diploma it was 74%.

Additionally, a study by the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank found having at least a four-year college degree is also associated with higher likelihood of owning a home and lower risk of “‘becoming delinquent on any obligation.’” At the same time, however, college graduates are not landing in jobs that actually utilize their college education. In early 2020, data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York showed over 40% of recent college graduates and over 30% of all college graduates were working in jobs that did not require a college degree. And yet, employers in 2019 reported talent shortages amongst the available workforce. This has resulted in more focus on technical training schools in lieu of – or as a precursor to – traditional college, as the surge in demand has been for technical skills. The Mike Rowe Works Foundation, for example, highlights the skills gap and stigma against vocational training.

Economist Bryan Caplan and Kite and Key Media share views on the value of a college education and what the role of vocational education can be

Bryan Caplan (5 min):

Kite & Key (6 min):

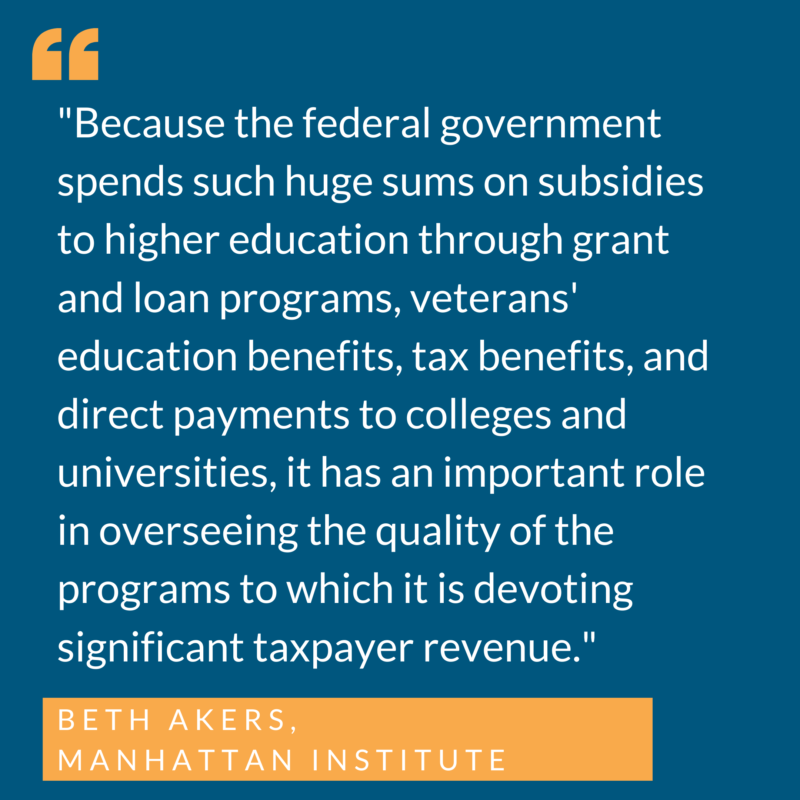

The Cost of a Diploma

Even though a college degree is still considered “worth it,” it is more expensive than ever. According to the Manhattan Institute’s Beth Akers, since 2000, private college tuition and fees have increased by over 50% beyond inflation and public school tuition and fees have increased by a full 100%. Aid and scholarships leave students with a final cost much lower than published prices indicate, but net costs have still been rising. This makes attaining a college degree even more difficult for students coming from low-income backgrounds; in the 1980s and 1990s, the “‘greatest widening of the gaps in enrollment between high- and low-income youth’” corresponded with the largest tuition increases. As “the cost of college increases, the returns for investment in education will decline unless there are corresponding increases in the wage premium paid to college-educated workers.”

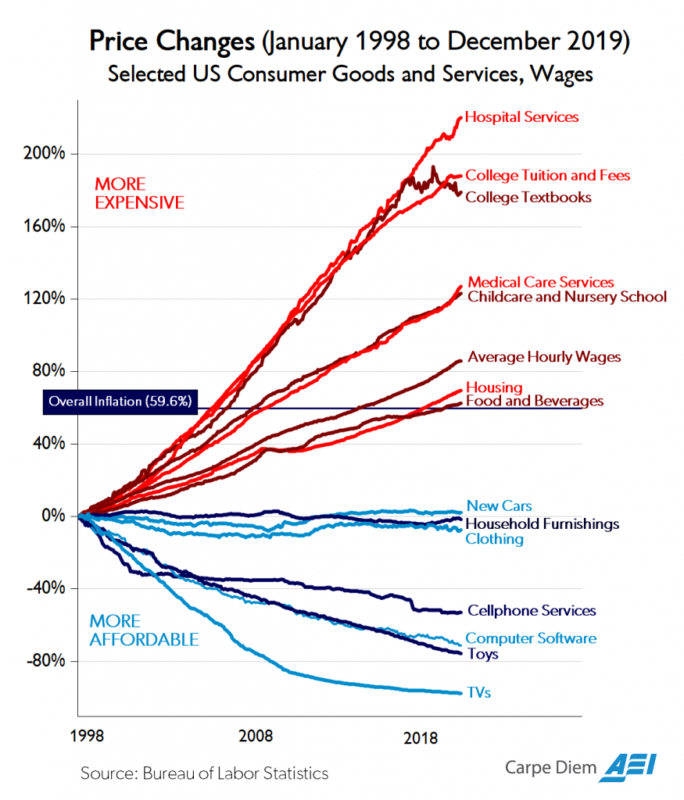

A report from Georgetown University analyzed data from the Census Bureau, Bureau of Labor Statistics, and the National Center for Education Statistics from 1980 to 2019, and found college costs have increased by 169% while earnings for workers ages 22 to 27 have increased by 19%. This chart from AEI’s Mark Perry demonstrates how average hourly wage increases have not kept up with the increasing costs of higher education:

What has caused these skyrocketing costs? Some point to administrative costs that have trickled down to students, such as pay increases for college and university presidents. However, there has also been a decline in money for professors and classes; the number of part-time faculty members has increased, whereas the number of full-time and tenured professors (who are paid more) have decreased in recent decades.

Others note that “in efforts to remain competitive with peer institutions,” many colleges “have amassed substantial debt and saddled students with additional fees to pay for services outside the academic core.”

The Bennett Hypothesis is also a common explanation. It suggests that colleges will increase their tuition if federal aid to students increases. Studies investigating whether schools do take advantage of increases in federal aid to raise their prices have found mixed results. Additionally, prices at public institutions are set through legislative processes involving incentives that do not necessarily correlate with federal higher education funding.

Another possible explanation is that the decline in state support of higher education has resulted in institutions passing more of the financial burden to students. Between 2008 and 2018, 41 states decreased their per student spending by an average of 13%. In 19 states, funding per student was cut by more than 20%. Tuition revenue exceeded state and local funding for higher education in 27 states in 2018, whereas that was only the case in 2 states in 1988.

At least 33 states allocate significant portions of their budgets based on performance funding (degrees completed, for example) even though evidence suggests performance funding has little or no impact on such outcomes. Instead, “‘evidence suggests states using performance-based funding do not out-perform other states,’” primarily because “states have implemented performance funding schemes while continuing to cut overall state funding,” leaving schools with fewer resources. These institutions often pass the financial burden on to students.

Beth Akers argues that these explanations, which come from the supply side (the higher education institutions) only tell part of the story, and that the demand side (students) also has a role to play. In a typical market, “suppliers compete with one another on quality and price,” and risk losing customers if they raise prices too much. However, the combination of complexity and inexperience leads many students to pursue higher education without closely examining their opportunities. This is especially an issue regarding federal loans without caps. To cover rising tuition costs, “[s]ome of the wealthiest U.S. colleges are steering parents into no-limit federal loans…leaving many poor and middle-class families with debt they can’t repay.” Among these no-limit, plus-sized loans, the average repayment rate among private four-year colleges was 39%; remaining parents “were paying only interest, causing their balances to grow, or had defaulted, were delinquent or asked to suspend payments.”

Additional information and transparency may help; for example, more attention to the College Scorecard – which requires every accredited college to publicly report information on its graduates’ earnings – could help hold colleges accountable for the outcomes they produce. Currently, most colleges are judged based on how they educate students (consider the prestige associated with certain higher education institutions) rather than specific outcomes such as first-year earnings or student loan repayment rates. The Wall Street Journal created a similar database for the debt-to-income ratio for a number of degree programs and schools. For example, WSJ analysis of federal student loan data found that for Master’s of Business Administration programs, graduates made more money two years out of school than they had borrowed at 98% of universities. Meanwhile, only 6% of law schools had programs where graduates had higher median earnings than debt two years out.

Excessive regulation among higher education institutions has also been called out. In order to gain eligibility for financial aid from the federal government, colleges must be accredited. This makes it difficult for new institutions to gain traction, particularly those offering different learning opportunities, such as fully online learning.

Janine Davidson of the Metropolitan State University of Denver discusses a few ideas to re-imagine higher education (13 min):

Student Loans

As mentioned above, as of November 2020, roughly 45 million Americans owed $1.7 trillion in student loans. Based on trajectory in recent years, prices are unlikely to decrease anytime soon, which has prompted discussions of whether (and, if so, how) to cancel student debt.

Proponents of cancelling student debt argue that debt holds workers back. Particularly for Americans who have scarce resources, some argue that “the need to keep making loan payments every month ties college graduates to their current jobs, making it riskier and more difficult to start a business or go looking for a better position. A one-time cancellation of debt could help spur economic growth by alleviating the pressure that prevents millions of Americans with student loan debt from engaging more in the economy.

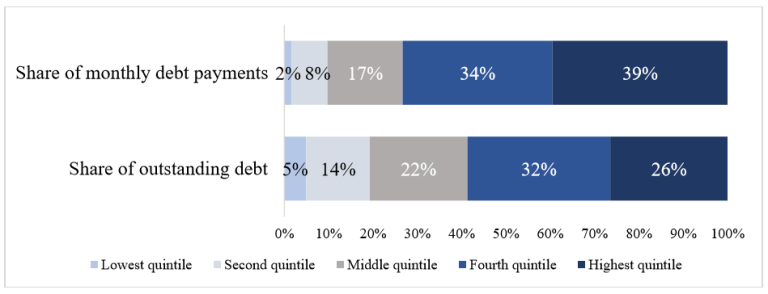

Critics of cancelling student debt say it would “disproportionately help upper-income households – college graduates, professionals with M.B.As, doctors, lawyers – while doing nothing for the tens of millions of workers who never went to college.” According to Brookings Institution, higher income Americans do owe the majority of student loans. The top 40% of households (based on income) owe 58% of outstanding education debt and make 73% of payments. Meanwhile, households in the bottom 40% of the income bracket hold less than 20% of debt and make only 10% of payments. For the most part, the lowest-income households consist of adults who did not go to college, and so they have little education debt.

AEI’s Michael Strain adds that while 14% of American adults hold graduate degrees, graduate degree-holders owe over half of student debt. In fact, 20% of education debt is held by 3% of adults with advanced degrees. One study by University of Chicago economists found that cancelling all student debt would be akin to giving the top 10% of households by income $78 billion (or $6,000 per household) while giving $12 billion to the bottom 10% (or $1,100 per household).

When looking at wealth instead of income, households with student debt tend to have the least amount of wealth; for borrowers in their 20s and 30s, debt is undermining their ability to save, invest, and build up wealth. Adam Looney, a Treasury Department economist during the Obama administration, suggests the possibility of using tax records to target debt forgiveness toward the borrowers who need it rather than an across-the-board cancellation. This could help the share of borrowers who dropped out of college because they could not afford to continue. Similarly, Beth Akers of the Manhattan institute suggests a cap of $5,000. As of September 2020, roughly 8 million borrowers are in default on student loans; many of these borrowers dropped out after one or two semesters, and even more who fell behind owed less than $10,000.

Finally, critics argue that taxpayers are the ones “who ultimately foot the bill for debt forgiveness, since federal loans were originated or guaranteed by taxpayer money.” Jason Delisle, resident fellow at AEI, adds that “the government-backed loan system provides funding without assessing borrowers’ ability to repay. So cancellation would do nothing to change the lending practices that led to the run-up in student debt,” nor would it attend to the skyrocketing cost of college tuition.

Coronavirus Implications

The challenges of student aid, loans, rising costs, and shrinking state budgets have only been exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic. The American Council on Education estimates that the coronavirus will cost institutions over $120 billion in “increased student aid, lost housing fees, forgone sports revenue, public health measures, learning technology and other adjustments.” For some perspective, the March 2020 CARES Act set aside $14 billion for higher education institutions. On the whole, Moody’s Analytics “predicts overall budget shortfalls ranging from 18 percent to 23 percent in fiscal year 2021.”

Financial instability across the nation has resulted in consolidated or suspended programs, from the University of Pennsylvania School of Arts and Sciences not accepting school-funded doctoral students next year, to Rice University hitting pause on admissions to its five Ph.D. programs in the School of Humanities. Other universities are laying off or furloughing employees, and initiating hiring freezes. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, colleges and universities across the country have shed over 300,000 jobs. Although these have been mostly non faculty positions, the presidents of some institutions have also been “firing professors and gutting tenure,” prompting nationwide complaints.

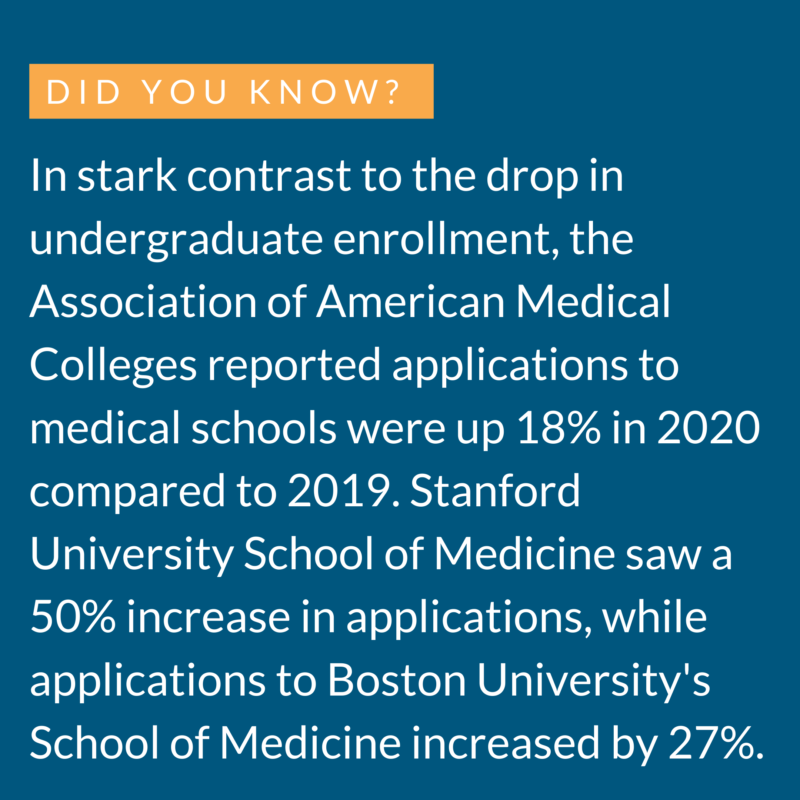

Meanwhile, students were left to consider whether online classes without campus activities are worth the tuition. According to an April survey by Education Technology firm Top Hat, 78% of college students felt “emergency online instruction was unengaging” and 68% thought it was “inferior to their typical face-to-face experience.” These results have manifested in deferrals and drops in enrollment. More than 700 Princeton University students (including 17% of the incoming freshman class) took deferrals or leaves of absence for the 2020-2021 school year. At Harvard, 20% of the freshman class chose to defer enrollment.

The National Student Clearinghouse Research Center reports freshman enrollment declined 13%. The number of 2020 high school graduates enrolling in college is down by almost 22% compared to 2019; in high poverty high school districts, it’s a decline of over 32%. Total undergraduate enrollment is down 3.6%, representing over 560,000 students. Total postsecondary enrollment is 3.4% lower than 2019. Community colleges saw the sharpest drop (18.9%), followed by public four-year institutions (10.5%) and private nonprofit four-year institutions (8.5%). Whether and how this trend continues will likely depend on the trajectory of the pandemic, but with fewer students for the time being, higher education institutions that were already strapped for cash are facing more difficulties.

Conclusion

Policies that were originally designed to expand opportunity and access to higher education have been met with skyrocketing costs, resulting in steadily increasing loans and debt for a large majority of students. The repercussions of the coronavirus pandemic have only placed additional financial burdens on both students and higher education institutions. For the betterment of society and the economy as a whole, considering how to approach and reform the systems that are resulting in rising tuition costs and mounting student debt will continue to be an important policy discussion.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Find out what your state and district are doing about higher education.

- Are you familiar with the higher education institutions in your state or county?

- Do you know your local/regional colleges’ graduation rates?

- How does your state appropriate funding for higher education institutions?

- Do vocational schools or technical colleges exist in your state or district?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Who are the members of your state’s Higher Education Board or Authority?

- Do you know who participates on the Board of Trustees at your local colleges, or at your own alma mater?

- What steps have your state’s or community’s elected or appointed officials taken regarding higher education?

- Investigate legislation your elected officials have sponsored or voted for with GovTrack.

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with community organizations, school boards and related organizations such as PTAs, your local chamber of commerce or local businesses.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, communications@thepolicycircle.org, for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policy makers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Talk to local businesses about skills gaps or hiring challenges they have faced, and whether or not possibilities for mentorships, internships, or apprenticeships exist.

- See if your local chamber of commerce will support ‘earn and learn’ opportunities or partnerships between education and workforce systems.

- Engage with community members in your school district, with school boards, or with PTAs to discuss possibilities surrounding vocational education options offered at your local schools.

- Reach out to local nonprofit organizations to see if they have partnerships for service-learning opportunities with nearby community colleges or four-year colleges.

- Look into education governance and the committees that set goals and visions, such your state’s Higher Education Board or local institutions’ boards of trustees.

- Investigate how your state presents financial aid opportunities, and what kind of scholarships, grants, and college-bound programs are available on your state’s Department of Education website.

- Engage with your local leaders and ask how the budget aligns with college attainment and training/re-training the workforce. Ask if your state has an attainment goal and how you can support the work to ensure it is reached.

- Mentor first generation, low income students to and through college.

- Contact your local United Way for a list of potential organizations or contact the K-12 or post-secondary institutions directly to ask how you can help!

Thought Leaders and Resources

Khan Academy: Exploring College Options

National Center for Education Statistics

National Student Clearinghouse

Michael Strain and Jason Delisle, AEI

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.