Introduction

Read the Executive Summary here. Watch The Policy Circle’s Move the Needle Virtual Event on foster care here. or The Policy Circle’s Leadership Summit panel on tackling foster care at the local level here.

In the United States, more than 400,000 children are in foster care on a given day. When speaking about child welfare, we often refer to the foster care system. This brief takes a closer look at the foster care system, key legislation, proposed reforms, and how children, youth, and young adults are impacted.

Case Study

In May of 2022, only a few hours after a visit from child welfare workers from the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services (DCFS), 8-year-old Amaria Osby was murdered by her mother. Amaria had been on the radar of DCFS since age 3, and at one point the DCFS office failed to make contact with Amaria or her family, or do a wellness check for 60 days after a call of neglect was reported. While the “department admitted rules were not followed in this case,” this story is a shocking and too often brutal reality of many understaffed and underfunded systems meant to protect and ensure the well-being of children across America.

Why It Matters

Child development can suffer if family ties are weakened by maltreatment and removal. Legal permanence is when a “child’s relationship with a parenting adult is recognized by law,” while relational permanence refers to long-term relationships that help young people feel connected. Permanence spanning both kinds is the goal for children in foster care, but a mix of confounding variables sometimes makes it difficult for child welfare agencies to achieve these goals.

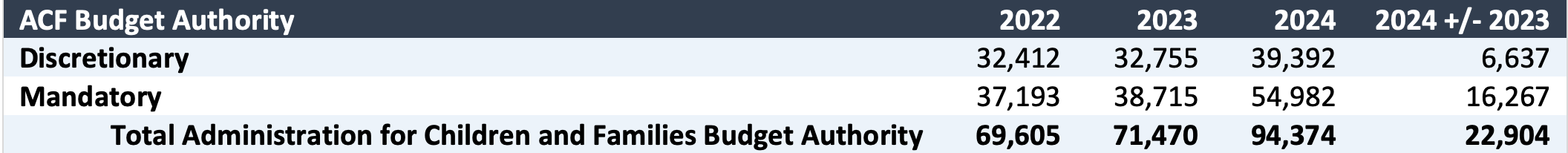

A significant amount of government and private sector funding goes to foster care children, which has implications for both public budgets and children’s futures. According to the requested FY 2024 HHS budget, the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) requests $94.4 billion. Foster care is interconnected to the juvenile justice system, substance abuse, human trafficking, healthcare, education, and employment. Since today’s children will be tomorrow’s adults, it is imperative that we stabilize and optimize the foster care system to care for society’s most vulnerable.

Putting It Into Context

Foster Care Basics

Foster care is defined as, “a temporary living situation for kids whose parents cannot take care of them and whose need for care has come to the attention of child welfare agency staff.” The ultimate goal is for children and youth to live in stable families, so foster care is meant to end once the parent or another relative can raise the child, or it is determined that the family cannot or will not care for the child.

When children are removed from their parents by public officials, the government assumes responsibility for their well-being. Specifically, caseworkers for child welfare agencies are responsible for children in foster care. The caseworker focuses mainly on the safety and basic needs of a child – such as schooling, medical care, shelter, and daily care. Caseworkers also monitor foster homes, reunite families, and find adoptive homes. Each foster child’s case is overseen by a judge.

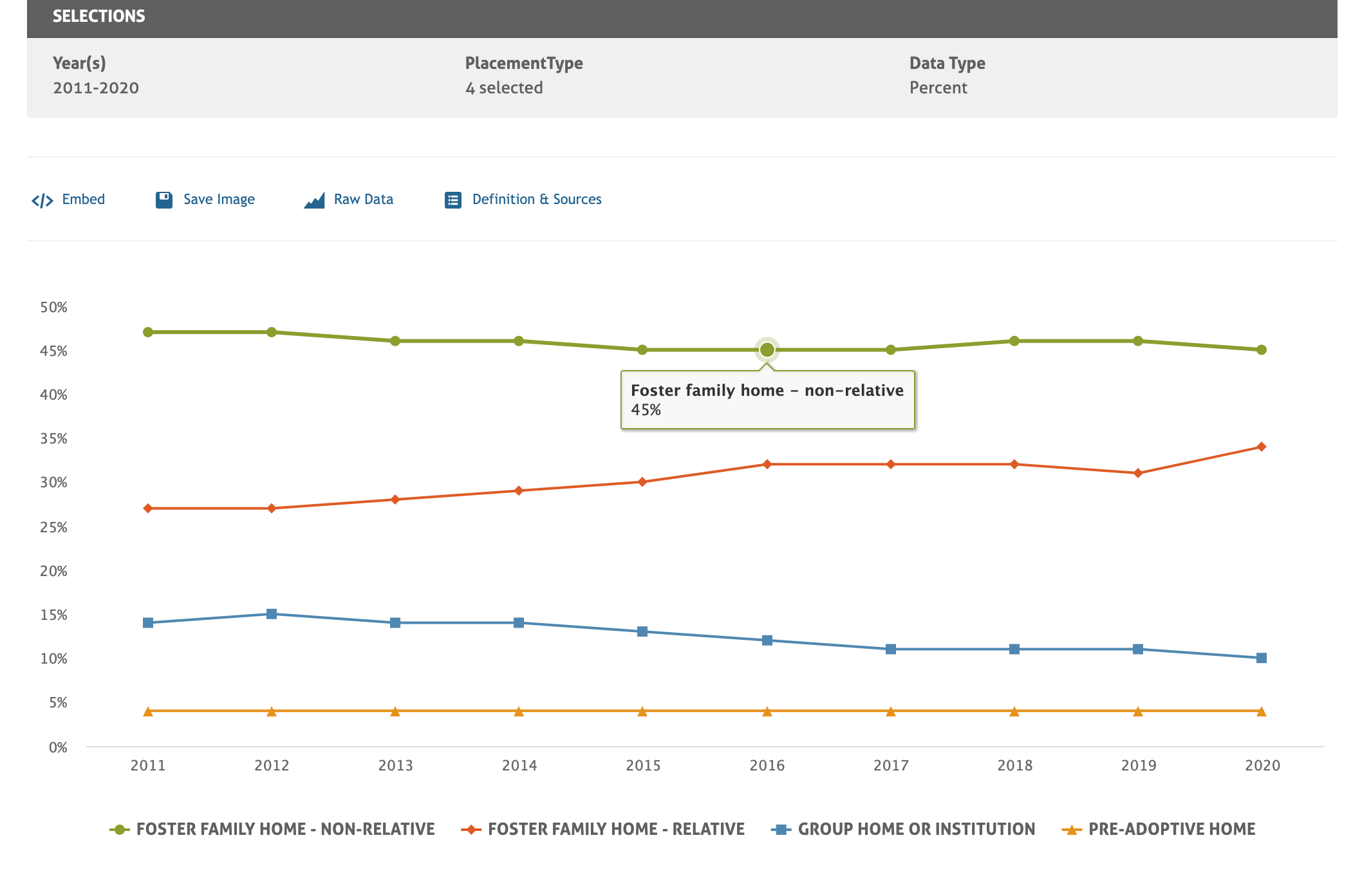

Foster care is usually divided into three categories of placement.

- Non-kinship care is when a vetted and trained foster family that is dedicated to caring for children steps in temporarily to raise them. To become foster parents, individuals must be selected, trained, and certified by their state’s Department of Social Services.

- Kinship care when children in foster care are placed with their own relatives.

- Group care involves specialized homes and other institutional settings. This is the least common path, but serves a need for youth that require certain mental or physical health services.

Defining Neglect

Under the Federal Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA), and as amended by the CAPTA Reauthorization Act of 2010, child abuse and neglect is legally defined as:

- “Any recent act or failure to act on the part of a parent or caretaker, which results in death, serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse or exploitation”; or

- “An act or failure to act which presents an imminent risk of serious harm.”

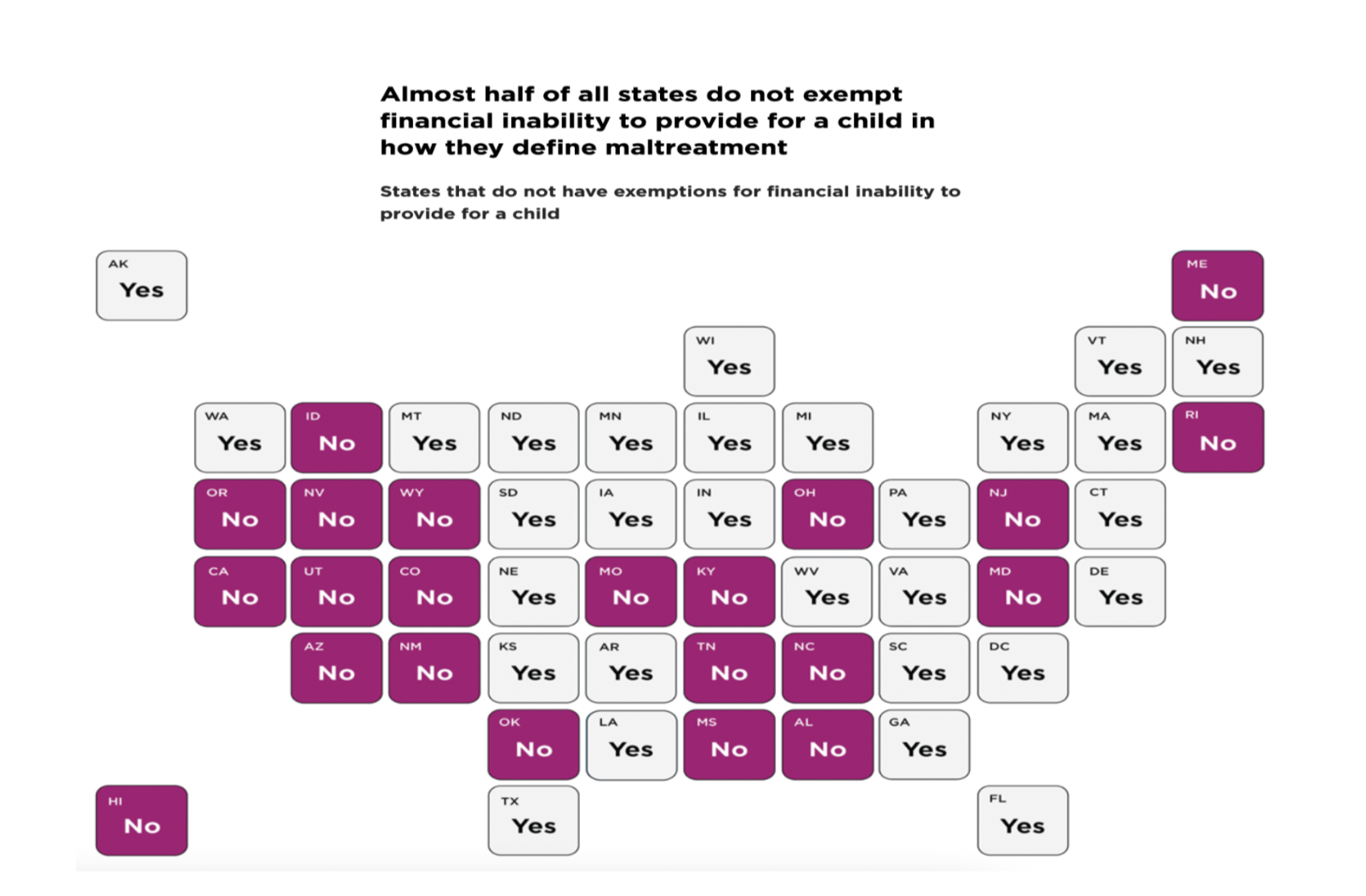

The Federal CAPTA legislation and definitions set the minimum standard, but each state must set its own legal definitions and understanding of maltreatment and neglect.

The Removal Process

The vast majority of investigations do not end in removals. Often parents are offered “in home services” or other kinds of support. Similar to the varying definitions of a state’s neglect or child abuse standards, the process of how a child is removed from a home and placed into the foster care system also varies. The general process typically begins with a formal complaint of child abuse or neglect reported to a local or state-based Department of Social Services. To find your state’s Social Service Agencies visit this link. Certain professionals are mandatory reporters to report any suspected abuse, including doctors, nurses, and teachers, though anyone can report child maltreatment. Once the complaint is made, the Department of Social Services conducts an investigation, and investigations can lead to court-issued Preliminary Protective Orders, Emergency Removal Orders, hearings, and placement in foster care. These processes serve as an investigation into the claims as well as an establishment of the relationship between the parent or guardian and the Department of Social Services. To learn more about the specific steps throughout this process, read more here about this local district’s process.

History

In the U.S., meeting the needs of children was seen as a private matter until the early 1800s. It was around that time that foster care was seen “as a societal problem in the United States that needed an organized solution.” The most influential development came in the 1830s when Minister Charles Loring Brace founded the Children’s Aid Society, an industrial school for the many homeless children in big cities in the Northeast. Brace also set up what is now known as the Orphan Train system, by which these children were transported to families in the Midwest. These youth were expected to provide extra help on farms in exchange for being part of the family, but the system provided no support after the children arrived at their destinations.

In the 1860s, state governments began paying families who took in children, and by the 1890s, started providing subsidies. By the early 1900s, the federal government “validated the authority of the state to step in and remove a child if they were a victim of abuse or neglect in the home.” This officially established the role of government in child welfare. In 1912, President Taft signed into creation the federal government department devoted entirely to child welfare, the Children’s Bureau. State-based social agencies began screening foster parents, keeping records, and providing services to families and children. The balance between state and federal responsibility for funding remained unclear. The issue was resolved with the 1980 Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act, which established a federal funding structure for child welfare services.

By The Numbers

Total Numbers

Roughly 5% of children in the U.S. are placed in foster care at some point during their childhood. This rate is similar to the global rate.

According to the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System’s (AFCARS) latest report (AFCARS Report #29 as of Feb 2024), the average age of foster children is 8, and about 30% of foster children are between 1 and 5 years old. The average time spent in the foster care system is 22 months, although 40% of all children and youth spend less than one year in the foster care system. There are slightly more boys (51%) than girls (49%). Black and American Indian children are overrepresented in the foster care system.

A recent study reported that within the United States, there were 615,000 victims of maltreatment (under age 18) in 2020. Of that number, 75% experienced neglect, about 20% were physically abused, 9% were sexually abused, and 6% were emotionally abused (percentages do not add to 100% due to multiple types of maltreatment in some cases). Further, a recent report, Fixing Our Child Welfare System to Help America’s Most Vulnerable Kids, revealed that throughout the country, deaths from child maltreatment are on the rise, with nearly 2,000 deaths reported in 2020.

Physical and sexual abuse have declined significantly since the 1990s (61% and 64%, respectively), while neglect has declined only slightly, from a high of 83% during the 1990s to about 70%.

Placements

Informal placements are the most common. This is often referred to as hidden foster care where the government finds a relative to place a child with but never technically removes the child into foster care.

Leaving Foster Care

Around 225,000 children and youth exit foster care annually. In FY2021 (report last update in October 2023), just over half (53%) of foster care youth were reunited with their parents or primary caretaker (slightly down from 57% in 2000). Another 37% were adopted; many times, foster parents adopt the child they fostered. About 10% aged out of the foster care system, known as emancipation.

Lifetime Impacts

The overall effects of time spent in foster care can vary greatly depending on the individual circumstances. There is no evidence that these are the effects of foster care. They are just as likely to be the effects of abuse and neglect before a child entered foster care. However, on average, people who have been in foster care tend to have more negative outcomes. According to the National Youth in Transition Database, almost 30% of former foster care youth experience homelessness by age 21. This number rises to 43% among American Indian young adults. Another 20% of former foster care youth report being incarcerated by age 21, and 25% report having had a child. Research also shows “students in foster care score 16 to 20 percentile points below their peers in state standardized testing.”

Compared to their peers not in the foster care system, those who turn 18 in foster care report 50% lower earnings and employment rates 20% lower, even among peers with similar education levels.

Role of Government

The U.S. Constitution declares it is the role of the government to promote the general welfare, ensuring the well-being of citizens, including children. States administer child welfare programs, but federal assistance and funding are both important components.

Federal

Federal child welfare policy has three main goals: “ensuring children’s safety, enabling permanency for children, and promoting the well-being of children and their families.” The Children’s Bureau, under the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), administers federal child welfare policy and seeks to achieve these goals by providing family services that allow children to reunite safely with their families, or by finding new, permanent families for children.

The Children’s Bureau oversees the main programs for foster care, coordinates with the Child Welfare Information Gateway and AdoptUSKids to provide resources for foster parents, and oversees the Foster Care Reporting System and the National Youth Transition Database. It also compels states to meet certain program requirements.

Besides overseeing the main programs for foster care, the federal government supplies technical support and training to states, tribes, courts.

Finally, federal funding for child welfare was established in the Social Security Act of 1935. Title IV of the act was for “Grants to States for Aid and Services to Needy Families with Children and for Child-Welfare Services.”

Federal transfers to the states are determined by the number of children in the state-run foster care system.

Supporting Agencies

While there are many key foster care-related programs, both locally and state-based, additional key programs for foster care come from the Children’s Bureau, and a number of other supporting mechanisms are coordinated by other agencies.

- Healthcare: Children that receive Title IV-E foster care payments automatically receive Medicaid since legal responsibility for these children falls to the states. Youth in foster care comprise less than 2% of all children enrolled in Medicaid. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has partnered with the Children’s Bureau to launch the Foster Care Learning Collaborative on Improving Health Care for Children and Youth in Foster Care.

- Education: Children in foster care tend to have worse standardized test scores and lower rates of graduation than their peers. The Department of Education has specific resources for youth in foster care. For example, there are specific provisions in the 2016 Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) for children in foster care enrolled in public schools. Additionally, the Department of Education has joined the departments of Health and Human Services, Housing and Urban Development, Transportation, and Labor to create the Foster Care Transition Toolkit “to inspire and support current and former foster youth pursuing college and career opportunities.”

See The Policy Circle briefs on Health Care Reform and K-12 Education for more on these topics.

Legislative Branch

Agencies such as the Departments of Education and Health and Human Services are part of the executive branch. However, the legislative branch plays an important role by having jurisdiction over many of these executive departments and their programs. The following Congressional Committees have jurisdiction over many of the programs mentioned above and other areas related to foster care:

- Within the House Committee on Ways and Means, the Subcommittee on Worker and Family Support has jurisdiction over bills and matters related to “public assistance provisions of the Social Security Act,” including child care, child support, foster care, adoption, and family services.

- Two Senate subcommittees have jurisdiction over the Administration for Children and Families and related programs, including the Foster Care and Adoption Assistance program. These are the Subcommittee on Children and Families, under the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor & Pensions; and the Subcommittee on Social Security, Pensions, and Family Policy, under the Senate Finance Committee.

Additionally, while it is not a committee with legislative jurisdiction, the Congressional Caucus on Foster Youth is “a forum for Members of Congress to discuss and develop policy recommendations to strengthen the child welfare system and improve the overall well-being of youth and families.”

State/Local

States “bear the primary public responsibility for ensuring the well-being of children and their families.” Child welfare systems are administered at the state level, or even the local level. Child welfare agencies work with courts and social services as well as health, mental health, education, and law enforcement agencies at these levels.

In general, every state’s Department of Social Services (or likeness) investigates reports of child maltreatment. In the most serious cases, the agency devises and administers a plan to help reduce the problems that led to the investigation and improve the situation for all family members. If that is not a feasible option, the agency removes the child from the setting and finds placement for the child outside of the home.

Although the federal government pays for large portions of foster care costs, states usually provide at least half of the overall funding. States, tribes, and localities cover about 56% of child welfare costs, but the percentage ranges from 50% to 83% across the country. Additionally, states and tribes pay roughly half of the administrative costs and about 75% of certain training costs. State agencies spend about $30 billion on child welfare purposes annually.

Variations By State

Foster Care Bill of Rights

As of 2019 (the most recent update), 15 states and Puerto Rico had enacted the Foster Children’s Bill of Rights and 17 states had enacted the Foster Parent Bill of Rights. A number of states have also enacted their own bills of rights for foster children and parents. Foster Children’s bills outline the rights available to foster care youth regarding “their safety, placement, health, education, finances, [and] court proceedings.” Foster Parent bills outline rights available to foster parents, including the right to “training, consultation, and assistance in evaluating, identifying, and accessing services” as well as the right to “information concerning behavioral problems, health history, educational status, cultural and family background, and other issues relative to the child[.]”

Licensing Requirements

To become a foster parent, each state has different requirements. The most common criteria are to be at least 21 years old and to provide proof of stable living accommodations. While states vary on specific requirements (some require citizenship, non-smoking homes etc.), all states mandate that potential foster families pass a criminal background check. Foster parents must also go through a minimum of 23 hours of initial training (many states require more). If individuals meet the general requirements, the state proceeds to license and approval, which usually entails a background check, fingerprinting, a training course, and proof of residency and financial stability.

Nine states disqualify anyone with drug-related crimes on their records; 18 states have minimum square footage requirements for homes; and 26 require a non-smoking environment.

States only receive federal subsidies for licensed homes. Examples of unlicensed homes may include kinship placements when relatives step in to care for a child. This also may generate some incentives for states to lower licensure requirements. However, ACF has released minimum quality standards, and while they are not binding, they do require states to explain how and why their licensing standards deviate from the national standards. The minimum quality standards include the requirement that; applicants must be able to communicate with the child, the applicant must be 18 years of age or older, and at least one applicant in the home must have functional literacy.

Placements

Placement rates vary considerably across states. In 2019, 3 of every 1,000 children were in foster care in New Jersey, while 15 of every 1,000 children were in foster care in West Virginia. Depending on the state, kinship care ranges from less than 10% of placements to nearly 50% of placements.

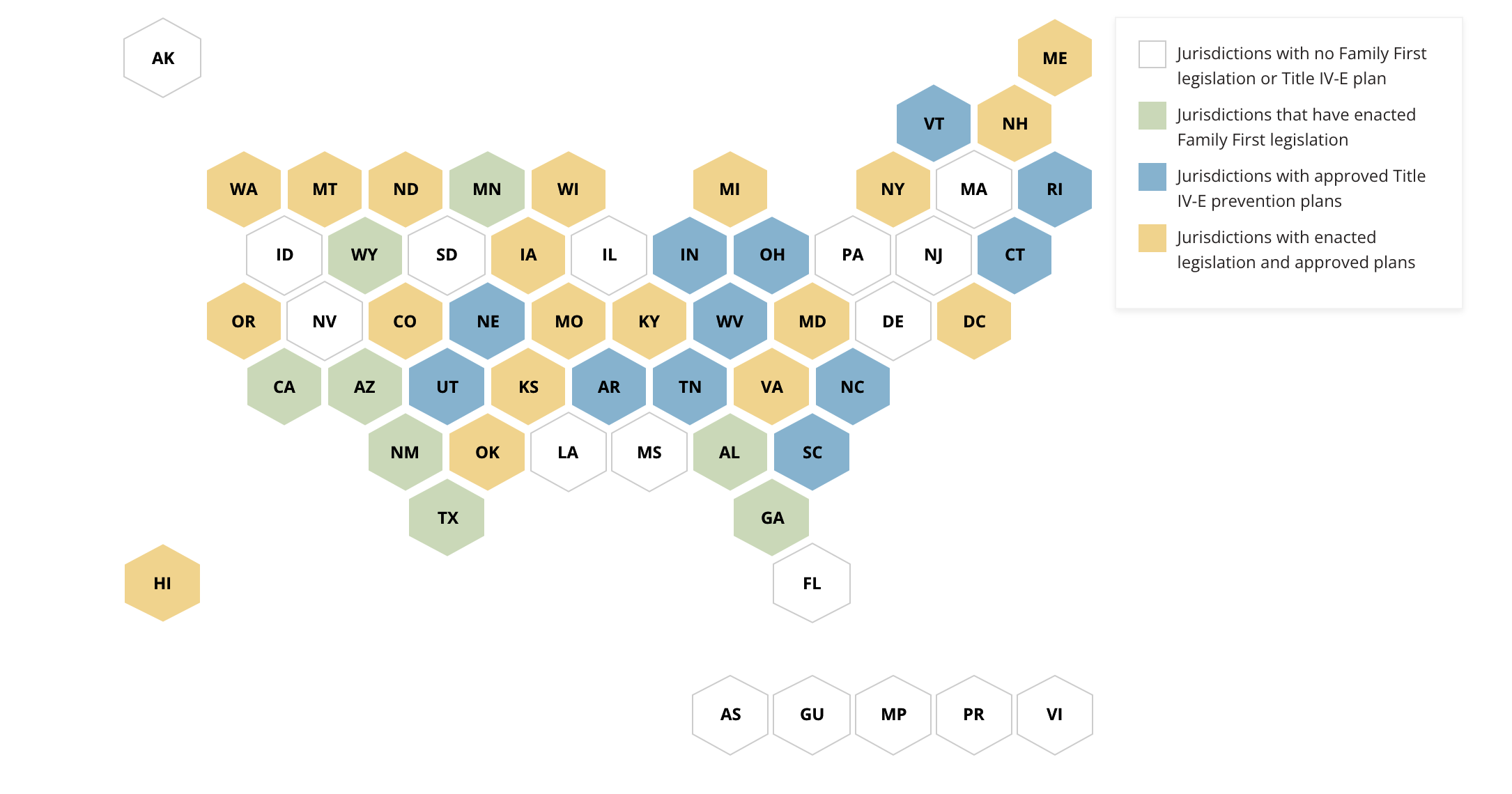

In order to comply with the 2018 Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA), many states enacted their own legislation to align with the new laws. By the end of 2021, 28 states and Washington, D.C. had enacted bills or resolutions addressing the FFPSA. Most of these laws officially define foster homes, group homes, and kinship placements so as to align with the Act. Some also established requirements for performance audits and other means to evaluate the implementation of the Act.

Private Sector

Guidance

The private sector is heavily involved in the foster care system. At the individual level, private citizens play an important role. Certain professions, such as educators and physicians, are required by law to report suspected maltreatment to local authorities. According to Health and Human Services, 21% of reports came from educators, 19% from law enforcement personnel, and 10% from medical personnel.

A number of organizations also provide guidance for foster care. For example, the American Academy of Pediatrics “is uniquely positioned to provide support and evidence-based guidelines to pediatricians caring for children and youth in foster and kinship care.” The Academy’s Council on Foster Care, Adoption, and Kinship Care recommends policies pertaining to health care issues children and youth in foster care face. The Academy also breaks down foster care models, programs, and projects by state.

Nonprofit Sector

Private organizations actually provide many public foster care services. Some states privatize almost all of their child welfare services, awarding contracts to nonprofit organizations (and in some cases, even for-profit entities).

A number of nonprofit organizations also work to provide foster care children with more support and resources. The Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Works Wonders curriculum includes courses, mentoring, job shadowing, and internships to connect foster care youths to careers that interest them. Foster Success’s programs are specifically geared towards educational success, financial empowerment, health and well-being, and workforce readiness for foster youth transitioning to adulthood. The goal of Starting Right Now is to end homelessness for foster youth by providing mentoring, stable living arrangements, employment opportunities, financial literacy, and life skills.

Other nonprofits in the foster care realm focus on supporting families and the rights of foster parents and children. Better Together, is an organization focused on keeping families together and children out of foster care. Better Together focuses on helping people help themselves through opportunities of employment, and providing a “loving, safe, and supportive foundation for their children.” Further, through Better Together’s focused program Better Families, they work to prevent the need of foster care by addressing some of the causes of child neglect and abuse.

PairTree compiles resources to help adopting families comply with state requirements and find legal resources such as family law and adoption attorneys. The Center for the Rights of Abused Children, formerly known as GenJustice, advocates for improving child welfare laws and laws that protect children. Areas of concern include household abuse, foster youth aging out of the system, improved education, and more resources to find missing and trafficked youth.

New technology has also been helping drive innovation and create solutions; Careportal is the “Uber of foster care,” and has levered technology to connect community organizations and charities with families in need. CarePortal CEO Joe Knittig shared, “every day, we have 350 children that are actually being served by their neighbors through CarePortal.”

Challenges and Areas for Reform

Prevention vs Protecting Children

States are trying to reduce the number of children in foster care, and for this reason, many have focused on prevention measures. This was the idea behind the 2018 Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA). However, some states may be giving too much weight to the declining number of children in foster care and are overlooking child maltreatment numbers. “[A]gencies and family courts are much more concerned with adults’ needs than with children’s safety.” – Naomi Schaefer Riley, Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute

For example, in Maine, the number of children in foster care slowed down, only growing by 12% between 2015 and 2019. The number of children experiencing maltreatment grew by 30%. According to Naomi Schaefer Riley, this could indicate “pressure was placed on child welfare workers to leave kids in their homes.” Riley suggests that federal funds allocated to states should include accountability measures to protect children.

To learn more about the challenges and how activism is impacting efforts to improve the child welfare system in detail, read Naomi Schaefer Riley’s book, No Way to Treat a Child: How the Foster Care System, Family Courts, and Racial Activists Are Wrecking Young Lives.

Additionally, you can watch this short video to learn more about the need for reform within the current child welfare system.

Children and Parental Rights

In some cases, children’s rights in foster care are fairly straightforward. Although an extreme example, a federal District Court judge ruled in 2015 that Texas violated the constitutional rights of foster children by “‘exposing them to an unreasonable risk of harm’.” In 2020, a 360-page report detailed threats to children’s safety, and a few months later two state officials were held in contempt of court for not following up on investigations of maltreatment or oversight of residential foster care facilities.

Balancing the needs and rights of children and families can be a bit more complicated. For example, the FFPSA was meant to generate more supportive mechanisms that would stabilize at-risk families and prevent them from being separated. But there are concerns that this could also intrude on parental rights; stabilizing families would require regular check-ups, raising the question of how much surveillance of families is too much, and where the goal of protecting children crosses a privacy line.

Matt Anderson, social worker and Vice President at the Children’s Home Society of North Carolina, explains the power of prevention, the rights of foster care youth, and how these ideas brought about the FFPSA (17 min).

Poverty vs. Neglect

Poverty is frequently linked to child maltreatment, such as in cases of foreclosures, evictions, housing insecurity, and food insecurity. Douglas Bersharov at the University of Maryland estimates roughly 85% of families investigated by Child Protective Services are below 200% of the federal poverty line. This is why some experts argue that poverty may be confused with neglect; Amelia Franck Meyer suggests these are the cases in which families need more support rather than separation. Children may not be properly fed or housed not because parents are neglectful but because they lack the means to do so. Stabilizing these at-risk families could help reduce demands on the foster care system. For more on this topic, see The Policy Circle’s Poverty Brief.

This is not all cases; as Sarah A. Font of Penn State University argues, sometimes changes in the economic situation at home would not help because substance abuse and mental health conditions are prevalent in these homes. A recent study of almost 300 case files in California, for instance, found that “nearly all investigations of physical neglect (99 percent) included concerns related to substance use, domestic violence, mental illness, co-reported abuse or an additional neglect allegation (i.e., abandonment).” Lynn Johnson of All in Fostering Futures notes a key issue is that neglect is hard to define, varying by state and even between individual investigators, and adding poverty confuses the situation even more. Being able to look into the home life situation and understand why the maltreatment is occurring is the best way to know whether support or separation is appropriate, but the line of too much surveillance of a home can be challenging.

Billing Families

One NPR investigation found it is common for parents to get bills for the cost of foster care. The 1984 Child Support Enforcement Amendments, along with a number of other state laws, calls for parents to pay for at least some costs of foster care, such as shelter, food, clothing, and administrative costs. States are legally allowed to garnish parents’ wages, take their tax refunds or stimulus checks, and even report parents to credit bureaus. A key problem here is that in families who cannot afford to take care of their children in the first place, this only sinks families further into debt and makes it more difficult for them to normalize their lives and provide stable living situations for their children.

A 2017 study found that charging parents one hundred dollars more per month in child support increased the time a child was out of the home by almost seven months. This is particularly concerning given that the 1997 Adoption of Safe Families Act (ASFA) pushes states to begin to terminate parental rights if children have been in foster care for 15 of the past 22 months. Essentially, “[b]illing parents for foster care undercuts the efforts of child welfare agencies to help parents and children reunite.” An additional dilemma is that findings in studies from California, Minnesota, and Washington indicate state governments spend a dollar for every 24 to 40 cents collected, meaning states are losing money in their efforts to bill families.

System-wide Problems

Lack of Resources

Almost every state reports a shortage of licensed foster homes; Texas and Washington have even reported children sleeping in child welfare agency offices. Overall, there is a need for more foster care; some claim training for foster parents is inconvenient or even difficult to access, and sometimes foster parents are not informed of children’s histories, such as past sexual abuse. As many as half of foster parents quit within the first year.

Within the system, one potential solution is a national database to measure foster home capacity and better evaluate matches for children. Another proposed option is to look outside the state system for more community support.

Beyond the shortage of foster homes, the child welfare system is overwhelmed and needs to do a better job of triage. Such an idea would require new data analytics; at present, Naomi Schaefer Riley of AEI argues that child welfare agencies do a poor job of determining which children are at high risk, which could be improved by technology improvements and data analytics. Potential data points include previous reports for abuse or neglect, or whether a child has missed school repeatedly.

A related issue is the fact that there is a 30% annual turnover rate at child welfare agencies, with some individual agencies’ turnover reaching 65%. With turnover comes the financial costs of recruiting and training new staff, as well as the qualitative costs coming from a less experienced workforce and discontinuity between caseworkers and families. Funding for training that states receive through Title IV-E is almost exclusively reserved for professional academic social work programs, but some suggest broadening this scope could help widen the potential staff pool. Examples include making training dollars available for individuals who have finished other professional degrees, such as criminal justice programs.

Placements

Congregate Care

In recent years, particularly evidenced in the Family First Prevention Services Act (FFPSA), there has been a movement away from group homes, also known as congregate care or institutional settings. Critics of institutional settings argue separating children from a family setting is damaging to their mental and emotional health. Others argue that many vulnerable children are only in group homes because of behavioral or mental health problems that foster parents or relatives would be unequipped to handle. The FFPSA has restricted federal reimbursements for group home care, which some argue makes it difficult for children to get the specialized care they may need.

Family

In 37 states and Washington, D.C., there are statutes that require child welfare agencies to “make reasonable efforts” to place siblings together. Still, more than half of children with siblings are separated from one or more of their siblings while in foster care. Part of this stems from the difficulty of placing siblings if there are significant age gaps between siblings, if individual siblings require different levels of care, or if there are insufficient resources at the state or local level, either in regard to available foster homes or organizational procedures.

Identifying kin could help keep siblings together, as well as provide better living situations for only children by keeping families intact. Additionally, identifying kin does not require extensive resources; New Mexico increased its initial kinship placement rate from 3% in 2019 to over 50% in 2021 simply by asking youths more questions about existing supportive relationships. Sarah Font of Penn State University adds that it is up to states to put effort into keeping families together, or prioritizing family reunification and even adoption; those that do tend to provide better outcomes for foster children.

Long-Term Impacts

Long-term impacts of foster care are mixed. A 2011 study that followed 730 foster care youth from age 17 to age 26 in Illinois, Iowa, and Wisconsin found low levels of post-secondary education and housing instability among the cohort. A 2019 study using data from South Carolina finds that juvenile delinquency is twice as likely among youth in foster care as it is for children that do not experience foster care.

Another study that ran from 2008 to 2016 in Michigan found that removing a child from home actually reduces the likelihood of subsequent maltreatment and improves school attendance. The 2019 South Carolina study also found that foster care placement reduced the likelihood that children would repeat a grade in school. Specifically, however, most gains from foster care placement “occurred after most [children] were reunified with their birth parents” and were “consistent with the rehabilitation of birth parents while their children were in foster care.”

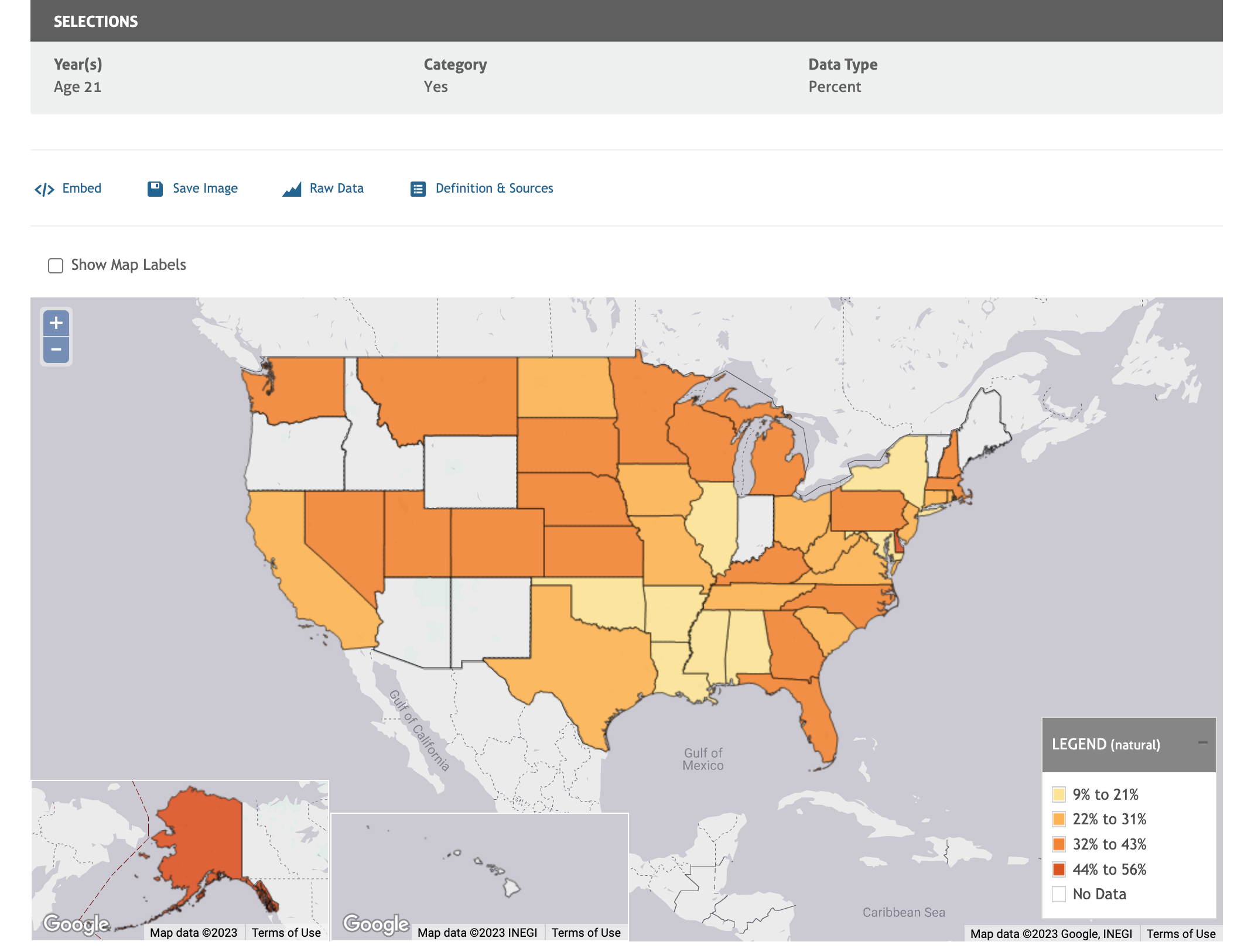

Aging Out

Aging out of the system is connected to high rates of PTSD, homelessness, unemployment, unplanned pregnancy, and incarceration. Issues in school can turn into limited work and training opportunities, resulting in low paying jobs that make individuals vulnerable to poverty. This vulnerability also makes these young adults more likely to experience homelessness. An average of 25% of young adults previously in foster care will experience homelessness within four years of emancipation, in part also because they lack cosigners and credit history. Health is another dilemma. Some states offer Medicaid for youth in foster care until they are 21 years old, while others end Medicaid eligibility and other forms of public assistance earlier, leaving these young adults with little support after they age out. For more on these topics, see The Policy Circle’s Briefs on Housing and the Affordable Care Act.

Sarah Font of Penn State University explains it is rare for children in foster care to age out; most of those who age out entered foster care during their adolescence. This makes it a bit tricky to make any statements about causation; was it foster care that generated the lifetime impacts, the living situation prior to foster care, or the combination of both?

Even without clear causation, policies that connect these young adults to transition services have proven effective. At the state level, Indiana’s Foster Youth Initiative started a voucher system from Public Housing Authorities to help the homelessness situation. In Mississippi, lawmakers created a fund “to help current and former foster youth pay for college tuition, fees, and room and board costs,” and even make it easier for them to rent apartments after emancipation.

At the federal level, the Fostering Connections Act of 2018 permitted states to start using federal funds for foster youth past the age of 18. Providing youth with support services after they turn 18 is known as extended foster care, which focuses less on care and more on academics, employment, and life skills. Not all states implemented the measures at the same time, allowing researchers to study the staggered rollout. They found that extended foster care “reduces the likelihood of homelessness and incarceration, and increases high school graduation and employment.”

Victor Sims explains what it is like to age out of the system, and what other potential solutions and supports could look like (7 min).

Conclusion

The U.S. foster care system is large, but not always well equipped. The current system does not always have the means or coordination to achieve the end goal, and goals are sometimes at odds with each other. Confounding variables ranging from substance abuse to poverty complicate matters. Given the long-term impacts on children and youth as they transition to adulthood and become functioning members of society, it is crucial to get this right by engaging not only institutions but the whole community.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Find out what your state and district are doing

- How many foster children are in your state? Use this resource to learn more about foster care statistics for your state.

- What are the rates for different kinds of placements? What are the long-term impacts of foster care on young adults in your state?

- The Child Welfare Information Gateway and Kids Count Data Center provide these statistics and more.

- What models, programs, and projects of foster care exist in your state?

- What are the foster licensing requirements in your state? What services exist?

- Has your state enacted a bill of rights for foster parents or children?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- See the State Foster Care Information Websites for more information on your states’ foster care system.

- Does your state partner with any local nonprofit organizations for services?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with first responders, faith-based organizations, local hospitals, community organizations, school boards, or local businesses.

- Faith-based organizations also share resources. To discover resources in your local community visit More Than Enough

- The National CASA/GAL Association for Children supports and promotes court-appointed volunteer advocacy for children and youth who have experienced abuse or neglect

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, communications@thepolicycircle.org, for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policymakers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot.

- Find nonprofit organizations in your area dedicated to child welfare