Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

Human trafficking is both a global and local issue. Each of us can make a difference by becoming more aware of the challenges and areas for reform, as well as taking action in our homes, businesses, and communities. For more on how to be involved and the three key components in the fight against human trafficking, watch this Policy Circle Move the Needle Experience with Heather Fischer, who served as Special Advisor on human trafficking to the President during the Trump Administration:

Case Study

In 2016, Kat was 16 years old and was struggling to see eye to eye with her parents. They argued frequently, and Kat began venting her frustrations to a man named Raphael she met on an app. Through the app, Raphael introduced her to Jesse, who offered to give her a ride from her home in Maricopa, Arizona to nearby Phoenix.

One night, Kat snuck out her bedroom window and got in a car with Jesse. She was subsequently blindfolded and driven 30 miles to a motel in Phoenix, where she met a third man named Bryant, who told her she had “a client.” The men continued to sell her for sex in hotels and homes around Phoenix until someone saw her and called an anonymous tip to the police. “I didn’t even know what sex trafficking was before I was taken. I didn’t know that I would end up in the situation that I ended up in,” Kat said.

When Phoenix hosted the Super Bowl in 2015, law enforcement, local elected officials, trafficking specialists, and community organizations coordinated their efforts to anticipate and fight potential trafficking surrounding the event. As a result, the Phoenix Police Department’s anti-trafficking unit, created in 2013, shifted its local strategy to a victim-centered approach. Recognizing that many women working in the sex trade may be exploited, local law enforcement began to prioritize identifying and prosecuting the perpetrators of sex trafficking, as opposed to focusing on arresting the workers. Kat worked with the anti-trafficking unit, which was then able to identify and arrest her three captors and even one of the men who had sex with her.

Kat spent nine months at the Phoenix Dream Center, a community-based shelter that specializes in caring for survivors of sex trafficking. There, she was able to bond with other survivors and receive physical and mental health care services necessary for her healing process. Meanwhile, Kat’s legal case against her traffickers took over two years to make it through the court system, similar to many other trafficking cases. She was forced to see her abusers denying the accusations, court date after court date, because without her testimony the case would fall apart. Finally, one of her captors cooperated with the police and all defendants took plea deals.

PBS’s Frontline investigation, Sex Trafficking in America, documents the Phoenix anti-trafficking unit’s work to protect trafficking victims like Kat and arrest their traffickers. You can watch the full film here.

What is Human Trafficking?

“Human trafficking,” “trafficking in persons,” and “modern slavery” all refer to both sex trafficking and compelled labor. In 2000, the U.S. passed the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA), landmark legislation that serves as the cornerstone of U.S. federal law combating human trafficking. According to the TVPA, human trafficking, trafficking in persons, and modern slavery all refer to “the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provisioning, patronizing, soliciting or obtaining” of a person for the purpose of a commercial sex act (sex trafficking) or for labor or services (labor trafficking) by means of “force, fraud, or coercion.” Sex and labor trafficking include but are not limited to involuntary servitude, slavery, debt bondage, and forced labor. In the case of child sex trafficking, when the victim is under the age of 18, the means of coercion is not necessary for the situation to be defined as trafficking; even without the use of force, minors are automatically considered to be exploited in these situations because they lack the ability to consent.

“Human trafficking,” “trafficking in persons,” and “modern slavery” all refer to both sex trafficking and compelled labor. In 2000, the U.S. passed the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA), landmark legislation that serves as the cornerstone of U.S. federal law combating human trafficking. According to the TVPA, human trafficking, trafficking in persons, and modern slavery all refer to “the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provisioning, patronizing, soliciting or obtaining” of a person for the purpose of a commercial sex act (sex trafficking) or for labor or services (labor trafficking) by means of “force, fraud, or coercion.” Sex and labor trafficking include but are not limited to involuntary servitude, slavery, debt bondage, and forced labor. In the case of child sex trafficking, when the victim is under the age of 18, the means of coercion is not necessary for the situation to be defined as trafficking; even without the use of force, minors are automatically considered to be exploited in these situations because they lack the ability to consent.

Human trafficking can cross international borders when victims are recruited abroad, or be entirely domestic. Even though the term trafficking is frequently associated with physical transportation, it’s not required. “For a person to be a victim of human trafficking…the individual must find him or herself in a context of exploitation,” by means of force or fraud.

This video from the Department of Homeland Security further defines what human trafficking is:

Why it Matters

When Representative Chris Smith first introduced in the late 1990s the act that is now the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA), the cornerstone of U.S. law to combat trafficking, “the legislation was met with a wall of skepticism and opposition“ because reports of “vulnerable people…being reduced to commodities for sale were often met with surprise, incredulity, or indifference.” Despite the disbelief, human trafficking was happening in our own backyards, and still is happening.

Simply put, human trafficking is incompatible with the fundamental principles on which the U.S. was founded: individual human rights, freedom of choice, the rule of law, and the safety and security of all citizens. Human trafficking fuels organized crime and violence, particularly drug trafficking as traffickers may force their victims to smuggle drugs across borders. Trafficking also drains resources from law enforcement and the public health system to treat victims who should never have been exploited in the first place. Every aspect and outcome of human trafficking endangers “the welfare of the individual, the family and the community” and thus tears at the fabric of society and the trust that allows communities and individuals to thrive.

Putting it in Context

By the Numbers

Who

Over 10,360 human trafficking cases involving nearly 17,000 victims were reported to the U.S. National Human Trafficking Hotline in 2021 (the latest report we have as of January 2023). You can see the breakdown of the calls to the hotline below, but due to the hidden nature of trafficking, the number of actual cases is likely much higher than what is reported. The International Labor Organization (ILO) reported in September 2022 (the most recent estimate available) almost 49.6 million people were living in modern slavery in 2021. Women and girls made up about 4.9 million of forced commercial sexual exploitation. Few estimates are available for human trafficking victims in the U.S. annually, as these statistics are notoriously difficult to obtain and confirm.

While very few estimates are available for confirmation, the Human Trafficking Institute publishes the Human Trafficking Report each year that provides an annual review of the human trafficking cases within the United States federal court system.

According to the 2022 report (the latest available in April 2024) there were 363 victims of human trafficking cases filed in the United States in 2022; of these new cases filed, adult victims comprised 39%, minor victims comprised 34%, and 28% were unknown ages.

Human trafficking victims often have “a vulnerability to exploit,” according to Megan Cutter, Associate Director of the U.S. National Human Trafficking Hotline. Groups that lack a strong support network and may be living on the edge of survival are at higher risk for exploitation. These groups include immigrants, refugees, and individuals experiencing poverty, homelessness, substance abuse, and histories of maltreatment. Children and adolescents who are abused, neglected, or in the foster care system are also likely to be trafficked. According to the Polaris Project, the most common recruitment tactics for sex trafficking are through an intimate partner (or potential partner, contacted through social media) or familial relation. For labor trafficking, it is through job offers and advertisements, or false promises and fraud.

According to the State Department’s 2021 Trafficking in Persons Report, the coronavirus pandemic created “conditions that increased the number of people who experienced vulnerabilities to human trafficking,” such as “the reduction of wages and work hours, closure of workplaces, rising unemployment, and reduced remittances, coupled with the rise in costs of living and disruptions to social safety networks”. This allowed traffickers to target families experiencing financial difficulties by offering fraudulent job offers. Many traffickers also took advantage of the shift online during the pandemic by increasing online recruitment tactics and contact via social media; there was a 22% increase in online recruitment during between 2019 and 2020, as well as a 125% increase in reports of recruitment on Facebook and a 95% increase on Instagram.

What?

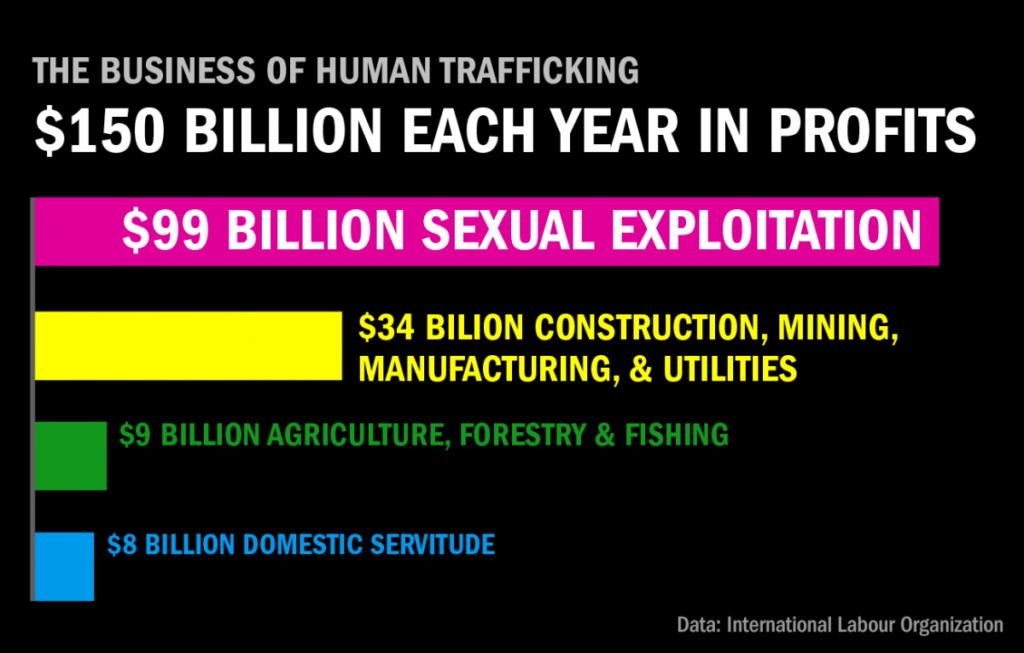

Trying to put a price on a human being is an unethical concept, but human trafficking does just that. The estimated annual profits per victim are $22,000 for sex trafficking victims and about $5,000 for labor trafficking victims. Added up, human trafficking globally generates over $150 billion annually for organized crime, making it second only to drug trafficking in terms of profit. Even though about 80% of victims are exploited for labor, over 65% of global profits come from sex trafficking.

Where?

Human trafficking cases have been reported in all 50 states, Washington, D.C., and some U.S. territories, but the U.S. National Human Trafficking Hotline reports the majority are from major cities including Houston, New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, Las Vegas, Columbus, and Miami. The following map illustrates likely locations of human trafficking cases based on hotline data. It is also important to remember that the most populous cities are connected by major roadways, so traffickers also transport victims from smaller, rural or suburban areas to these larger locations. You can find statistics and facts about human trafficking in your state here .

Worldwide, the Asia-pacific region accounts for the largest number of forced workers (15.4 million), followed by Africa (5.7 million), Europe and Central Asia (2.2 million), and the Americas (1.2 million). Technology and the means of luring victims via phone and the Internet have helped spread the proliferation of human trafficking.

History

In the 1990s, a series of high profile labor and sex trafficking cases “demonstrated that egregious forms of modern slavery persisted, hidden in plain sight, in communities across the United States.” What the cases also demonstrated, unfortunately, was how insufficient existing criminal statutes were and how little “interdisciplinary partnerships” existed among U.S. law enforcement agencies, victim assistance nonprofits, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) in investigating such cases.

The U.S. was not the only country with these concerns. In 1995, China hosted the United Nations’ Fourth World Conference on Women. It produced the Platform for Action, which became “a global policy framework and roadmap for government implementation” that included the need to eliminate trafficking. Five years later, the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime in Palermo, Italy in November, 2000 produced the Palermo Protocol, the “first effort by the global community to create an internationally recognized set of standards relating to human trafficking and combating organized crime.” The Palermo Protocol established two core principles for combating human trafficking. First, to follow the “3P” paradigm of prosecuting traffickers, protecting victims, and preventing trafficking. Second, to follow a victim-centered approach, “which places equal value on the identification and stabilization of victims” as well as the prosecution of traffickers. The U.S. and many other countries incorporated these aspects into their laws combating human trafficking.

The Role of Government

Federal

In 1999, New Jersey Congressman Chris Smith introduced bipartisan legislation that served as the framework for the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA), which was proposed by Minnesota Senator Paul Wellstone in 2000. The 2000 TVPA became the cornerstone of U.S. federal law on human trafficking. It established the President’s Interagency Task Force to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons (PITF); the Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons (TIP) within the Department of State; and the TIP’s annual Trafficking in Persons Report.

In 1999, New Jersey Congressman Chris Smith introduced bipartisan legislation that served as the framework for the Trafficking Victims Protection Act (TVPA), which was proposed by Minnesota Senator Paul Wellstone in 2000. The 2000 TVPA became the cornerstone of U.S. federal law on human trafficking. It established the President’s Interagency Task Force to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons (PITF); the Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons (TIP) within the Department of State; and the TIP’s annual Trafficking in Persons Report.

Over fifteen federal agencies make up the PITF, including the Department of State and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) to combat transnational trafficking, and the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, which must adhere to federal laws that prohibit importing goods made with trafficked labor. The Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, the Offices of Management and Budget, the National Security Council, and the Domestic Policy Council also participate. Such interagency cooperation at the federal level is an important component in ensuring human trafficking remains a significant policy issue.

The Policy Circle Co-Founder Sylvie Légère attended the White House Summit on Human Trafficking in January 2020, where a panel of state representatives, law enforcement groups, and judges from several states, cities, counties, and Native American reservations addressed collaboration and coordination efforts. Read more about the event here.

Another vital component in establishing anti-trafficking strategies is relying on the experiences of private citizens. The brave survivors of human trafficking are a valuable source of information, and their voices need to be incorporated into these strategies. The U.S. Advisory Council on Human Trafficking is comprised of eight human trafficking survivors who provide recommendations to the PITF on federal policy and programs. Additionally, training and assistance programs from the Department of Justice, the Department of Health and Human Services, and the Department of State all include networks of consultants who are either survivors or subject matter experts.

State and Local

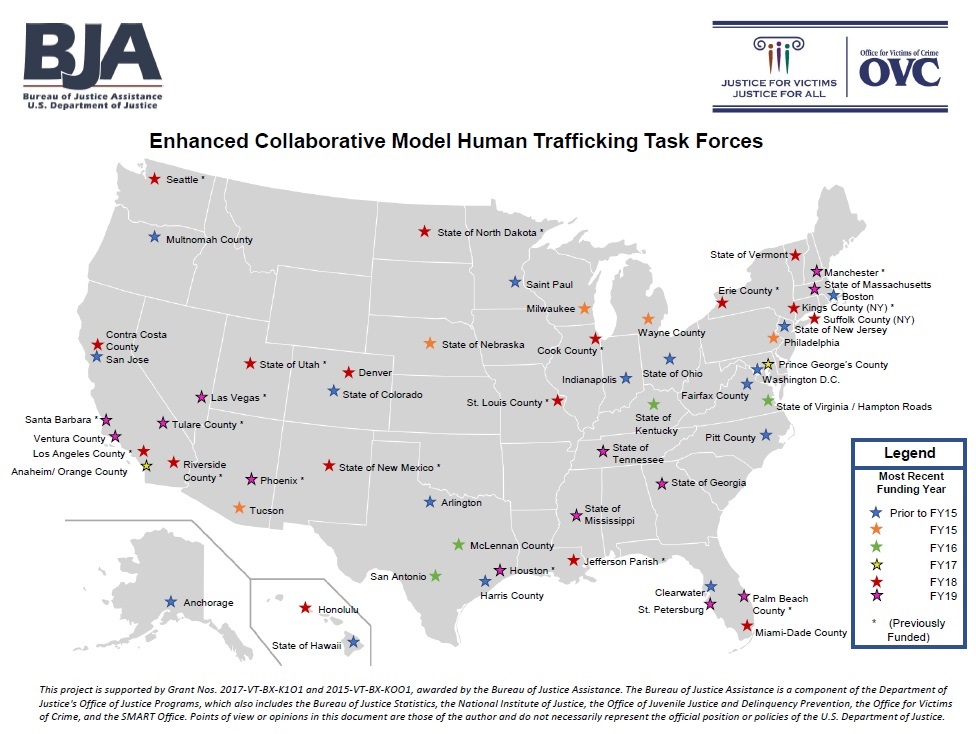

Between 2004 and 2013, all 50 states and the District of Columbia enhanced their anti-trafficking laws. Additionally, to best implement the “3P” paradigm, local agencies in health, social services, law enforcement, and justice coordinate their activities to prosecute traffickers, protect victims, and prevent trafficking across state and county lines. The Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) under the U.S. Department of Justice has developed training programs to help local law enforcement agents identify and rescue victims, because local law enforcement personnel are often the first to encounter victims. Other members of civil society in the fight against human trafficking include local NGOs, faith-based organizations, survivors of human trafficking, media, and academia. In many cases, NGOs and faith-based organizations are the first line of defense and places of refuge for victims. Strengthening them and the resources they have in turn strengthens communities. See which community organizations in your state have received grants from the Department of Justice and the Department of Health and Human Services.

Between 2004 and 2013, all 50 states and the District of Columbia enhanced their anti-trafficking laws. Additionally, to best implement the “3P” paradigm, local agencies in health, social services, law enforcement, and justice coordinate their activities to prosecute traffickers, protect victims, and prevent trafficking across state and county lines. The Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) under the U.S. Department of Justice has developed training programs to help local law enforcement agents identify and rescue victims, because local law enforcement personnel are often the first to encounter victims. Other members of civil society in the fight against human trafficking include local NGOs, faith-based organizations, survivors of human trafficking, media, and academia. In many cases, NGOs and faith-based organizations are the first line of defense and places of refuge for victims. Strengthening them and the resources they have in turn strengthens communities. See which community organizations in your state have received grants from the Department of Justice and the Department of Health and Human Services.

Victims have access to state and local services that are funded by block grants, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Substance Abuse and Mental health Services Administration (SAMHSA). The Department of Health and Human Services’ Domestic Victims of Human Trafficking Program also provides victim assistance grants to state, tribal, and local organizations and programs providing victim-centered services so as to help “build community anti-trafficking capacity.” These organizations include food pantries and soup kitchens; domestic violence and homeless youth shelters; legal aid clinics; job training programs; ESL and GED assistance programs; and immigrant community organizations. Victims can identify where to get emergency, transitional, or long-term support services from local organizations by calling the U.S. National Human Trafficking Hotline, and individuals can identify and support the NGOs in their community by using the hotline’s Referral Directory.

Current Challenges and Areas for Reform

Information Gathering

To properly combat human trafficking, organizations and agencies need reliable data, which is difficult to acquire. Primary data collection is complicated by the sensitive nature of the information and the need to ensure data integrity and confidentiality. Even with considerable amounts of gathered information, costs of building and maintaining databases is limited to committed governments and well-funded organizations. The majority of organizations around the world rely on basic databases or even paper files.

In the U.S., there are two main federal databases that record and track U.S. crime data, the Uniform Crime Reporting Program and the National Incident-Based Reporting System. The National Hotline also compiles data and statistics based on the calls it receives, and shares this data with the primary international database, the International Organization for Migration’s Counter Trafficking Data Collaborative (CTDC). This global database is an endeavor to pull together organizations around the world to make human trafficking data publicly available. The Department of State’s annual Trafficking in Persons report also details trafficking statistics by country, and what measures, if any, each country employs.

Working with Communities

Address Cultural Norms

In the U.S., “there’s a tendency to view human trafficking only as an international or transnational crime,” even though the U.S. is both a source and destination country for human trafficking. Combating this misconception is a key part of the domestic fight against human trafficking. A second major part of the fight is creating cultural change by reducing the demand for trafficking; according to the Demand Abolition investigation, Who Buys Sex?, active buyers of prostitution say it is “a ‘mostly victimless’ crime and are less likely to say that prostitution is a crime ‘where someone is harmed’.” In reality, people working in the sex trade are often exploited. At the local level, we as individuals can make a big difference by addressing the prevalence of sex trafficking and the morality of exploitation. Having these difficult but important conversations can help dispel myths so family and community members are aware of the risks and understand the truth of trafficking.

In the U.S., “there’s a tendency to view human trafficking only as an international or transnational crime,” even though the U.S. is both a source and destination country for human trafficking. Combating this misconception is a key part of the domestic fight against human trafficking. A second major part of the fight is creating cultural change by reducing the demand for trafficking; according to the Demand Abolition investigation, Who Buys Sex?, active buyers of prostitution say it is “a ‘mostly victimless’ crime and are less likely to say that prostitution is a crime ‘where someone is harmed’.” In reality, people working in the sex trade are often exploited. At the local level, we as individuals can make a big difference by addressing the prevalence of sex trafficking and the morality of exploitation. Having these difficult but important conversations can help dispel myths so family and community members are aware of the risks and understand the truth of trafficking.

In January 2022, Representative Ann Wagner (R-Mo.) introduced the Sex Trafficking Demand Reduction Act. Had it passed, it would have amended the TVPA to ensure the State Department’s annual Trafficking in Persons report takes into account what foreign countries are doing to reduce the demand for commercial sex. This follows one of the key principles of the Nordic Model: to reduce demand by making it clear “that buying people for sex is wrong.”

Empower Communities

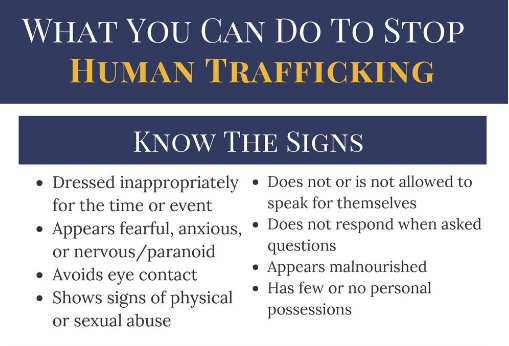

“Coordinated, community-based approaches that are customized to address a range of vulnerabilities across diverse groups may prevent human trafficking before it begins.” Empowered individuals are best equipped to address the needs of their specific communities. This includes addressing violence, crime, and housing risk factors in neighborhoods; encouraging local businesses to monitor their supply chains; supporting specialized clinics and NGOs that provide social services and services for the physical and mental health of survivors; and developing educational programs for at-risk youth or the general public. Training initiatives for law enforcement, private sector employees in industries such as healthcare, transportation, and education, and individuals will also help community members understand and identify the signs of trafficking, and know which questions to ask if they believe someone is being trafficked. You can start here with these informative videos from the Department of Homeland Security’s Blue Campaign, and by learning how to identify labor and sex trafficking.

Once community members are trained to identify the signs of trafficking, they can feel more confident in their ability to combat human trafficking. One program from the Department of Justice’s Office for Victims of Crime develops human trafficking task forces, multidisciplinary teams formed by partnering local law enforcement agencies and community victim service organizations with state and federal agencies. You can find human trafficking services and task forces in your state with the Office for Victims of Crime map, or consider working with your local officials to form your own task force with the Office for Victims of Crime’s Human Trafficking Task Force e-Guide.

Community members can also engage with the U.S. National Human Trafficking Hotline. Operated by Polaris, the hotline focuses on assisting victims and survivors, but anyone can contact the hotline (or directly call 911) to report a tip or a suspicious situation. The hotline has also compiled resources for anyone looking to engage in training or volunteer efforts in their communities. Community organizations are often in need of donations such as food or first aid and cleaning supplies, or volunteers to help with drives or fundraising events. Watch what these students in Atlanta are doing to help fight human trafficking.

The coronavirus pandemic did make this more difficult as governments around the world diverted resources towards the pandemic and organizations suffered funding cuts. One survey from UN Women in coordination with the Office of Security and Co-operation in Europe’s Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (OSCE) found only 24% of 385 anti-trafficking organizations that responded to the survey could remain fully operational during the pandemic.

Prosecution and Protection

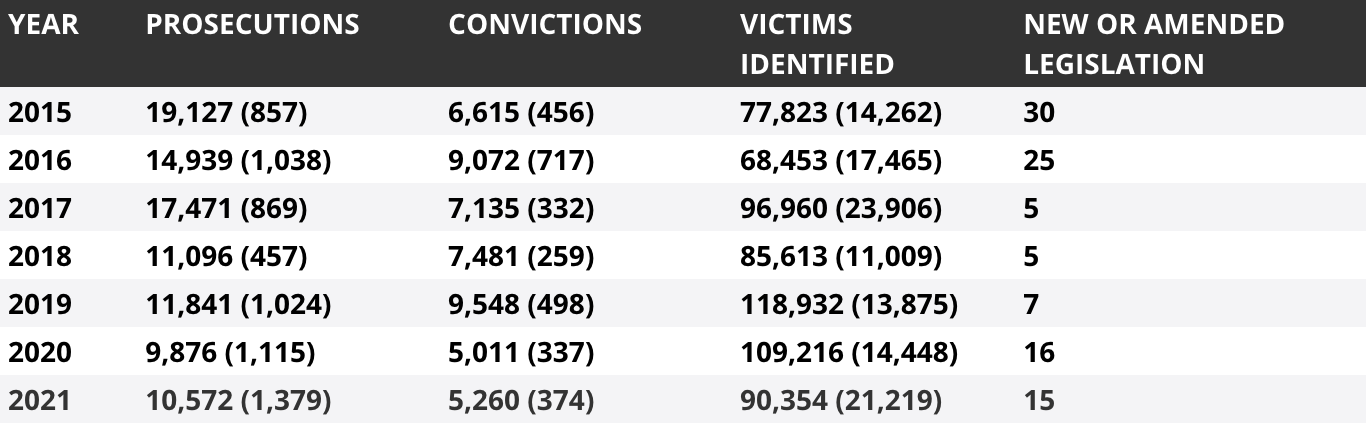

The U.S. Department of State estimates that 16 million people worldwide were victims of forced labor in 2016, leading to only about 1,000 prosecutions. The global data in the chart below, from the department’s 2022 TIP Report, shows a decline in prosecutions – one that was made worse by additional burdens placed on law enforcement during the COVID-19 pandemic, and a slight uptick in 2021.

In 2020, a total of 2,198 persons were referred to U.S. Attorneys for human trafficking offenses which was a 62% increase from the 1,360 persons referred in 2011, according to the most recent available data in 2022 Human Trafficking Data Collection report.

Prosecution efforts across the world tend to lean in favor of the perpetrator. Even with the acknowledgement of the Palermo Protocol, there are no international standards for prosecuting human trafficking crimes. For example, labor trafficking cases can sometimes be prosecuted under employment law for labor violations, resulting in penalties much weaker than they would be if prosecuted under anti-trafficking law.

U.S. Coordination and Collaboration

Where it can, U.S. law enforcement collaborates internationally, such as with Mexican law enforcement officials at the border in the U.S.-Mexico Bilateral Human Trafficking Enforcement Initiative to “facilitate exchanges of leads, evidence, intelligence, and anti-trafficking expertise.” This is essential, given the number of migrants endeavoring to enter the U.S. at its southern border, particularly for unaccompanied minors who can be exploited (see The Policy Circle’s Immigration Brief for more on the situation at the border.)

Domestically, the 2019 Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act requires the Department of Justice to appoint a U.S. Attorney as a Human Trafficking Justice Coordinator in each federal judicial district, and Anti-Trafficking Coordination Team (ACTeam) Initiative combines resources and personnel from the Departments of Justice, Homeland Security, Labor, and the FBI to develop and implement strategic enforcement plans in districts across the country.

Protecting Victims

Protecting Victims

These coordinated efforts not only help law enforcement and the Department of Justice better prosecute traffickers, but also protect, rather than prosecute, victims. Victims’ testimonies are essential to successful human trafficking prosecutions, yet their participation in the legal process is often limited by fears for their safety, being arrested, or in the case of victims of international trafficking, being deported. Addressing these fears is an important part of protecting victims. Victims of international human trafficking may be eligible in the U.S. for Continued Presence (CP), “a temporary immigration status provided to individuals identified by law enforcement as victims of a ‘severe form of trafficking in persons’ who may be potential witnesses.” At the state level, safe harbor laws protect children from criminal liability for prostitution or nonviolent offenses committed as a result of being victims of human trafficking, as exploited children are often further manipulated to commit other crimes. These safe harbor laws also ensure child victims have access to specialized services including medical and psychological treatment, legal services, and education or employment assistance.

One barrier to keeping victims safe has been the coronavirus pandemic, as many survivors were pressured by former traffickers if they faced financial difficulties and social isolation brought on by the pandemic. The UN Women/OSCE survey found that during the pandemic, survivors’ access to employment decreased by 85%, to medical services by 73%, to social services by 70%, to legal assistance by 66%, to psychological assistance by 64%, and to safe accommodation by 62%.

The Role of Big Tech: Section 230

In the United States, traffickers recruited 55% of sex trafficking victims online in 2021, according to the most recent data in the Human Trafficking Institute’s 2021 Federal Human Trafficking Report.

In the United States, one piece of legislation that has garnered controversy in the fight against human trafficking is Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act. According to Section 230, a website’s users “are ‘solely responsible for their own behavior’,” meaning a website or Internet Service Provider cannot be held legally responsible for what users or third-parties publish on their platform. Supporters of Section 230 credit it with greatly benefiting the American economy, paving the way for innovation online and allowing “YouTube and Vimeo users to upload their own videos, Amazon and Yelp to offer countless user reviews…and Facebook and Twitter to offer social networking to hundreds of millions of Internet users.”

In terms of human trafficking, critics argue Section 230 could be subjecting victims of trafficking to increased harm. A New York Times investigation disclosed “an explosion of abusive content” on tech companies’ platforms over the course of 2018 and 2019, including over 45 million photos and videos of children being sexually abused. First, this indicates high demand for these images, which drives more child abuse. Second, under Section 230, platforms are immune from liability, which makes protecting victims, preventing future crimes, and prosecuting traffickers more difficult.

Advertising websites like Backpage.com are at the center of these criticisms. In 2017, Senator Rob Portman of Ohio, co-chair of the Senate Caucus to End Human Trafficking, introduced the bipartisan Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act (SESTA). SESTA was signed into law in April 2018 and was the first step toward holding websites like Backpage accountable for facilitating online sex trafficking. The documentary I am Jane Doe “chronicles the epic battle that several American mothers are waging on behalf of their middle-school daughters, victims of sex trafficking on Backpage.com.” See the trailer below, or watch the film on Netflix.

Private Sector Role

According to Human Rights First, 70% of trafficking happens in the private sector. In the U.S., the highest number of reported labor trafficking cases were in domestic work, agriculture, traveling sales, food service, and health and beauty services. The following chart breaks down the most profitable trafficking sectors worldwide.

Especially in high risk industries, it is critical for business owners to be responsible for paying their employees fair wages, knowing their workers’ rights, and knowing their supply chains. Additionally, businesses can join the fight against trafficking by educating employees to identify warning signs and developing protocols for reporting suspicious activity to law enforcement. For example, the Department of Health and Human Services offers a training program for healthcare and social service professionals, and the Department of Labor has a program to help businesses develop a social compliance system.

The long-standing U.S. Tariff Act of 1930 prohibits importing goods made with forced labor, but “U.S. law doesn’t require large multinational corporations to monitor their supply chains for forced labor… it’s generally up to the corporations to self-police and to prioritize eliminating slavery from their global supply chains.” Even in the reauthorization of the TVPA, there are few requirements for private corporations.

Many businesses have taken it upon themselves to make these efforts because investors and consumers indicate through their buying preferences their concerns regarding enhanced protections for workers. For example, the Responsible Business Alliance (originally Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition, EEIC), the RESPECT Initiative, and Stronger Together work to help businesses identify and prevent modern slavery in their supply chains. They provide resources to help businesses understand how to improve working conditions and how to recruit and source ethically and responsibly. Additionally, the Global Business Coalition Against Human Trafficking supports survivors by providing them with access to job training and employment opportunities.

Many businesses have taken it upon themselves to make these efforts because investors and consumers indicate through their buying preferences their concerns regarding enhanced protections for workers. For example, the Responsible Business Alliance (originally Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition, EEIC), the RESPECT Initiative, and Stronger Together work to help businesses identify and prevent modern slavery in their supply chains. They provide resources to help businesses understand how to improve working conditions and how to recruit and source ethically and responsibly. Additionally, the Global Business Coalition Against Human Trafficking supports survivors by providing them with access to job training and employment opportunities.

Governments can also play a role, as seen when the U.S. and other countries stepped up criticism of Chinese treatment of Uyghurs and other Turkic Muslims in Xinjiang. With the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevent Act, the U.S. bans goods produced by Xinjiang workers in state-run programs unless importers prove no exploitation occurred. Rights groups and researchers have accused Xinjiang authorities of mass internment and exploitation of Uyghurs, while Chinese government officials claim it is a labor transfer program. Thus far, the results have been for many factories that make products sold in the U.S. to shun workers from Xinjiang.

We as individual consumers can participate in the fight against human trafficking by educating ourselves about our own impacts on human trafficking. You can take this survey to understand your own slavery footprint or visualize the risk of forced labor with Responsible Sourcing Tool’s map. We can choose to support businesses that make efforts to prevent modern slavery in their supply chains, as well as support human trafficking survivors or business models that provide jobs and employment for those at risk of human trafficking, such as the Nomi Network. End Slavery Now also provides lists of companies with transparent supply chains, fair trade products and companies, survivor-made goods, and how you can write a letter to a company.

Conclusion

Human trafficking can and does happen anywhere in the world – from countries across the ocean to our own neighborhoods. For this reason, cooperation across domestic borders and international boundaries, between the public and private sector, and among the local, regional, state, and federal levels is essential to combating human trafficking. Combined efforts to recognize and prevent human trafficking, protect victims, and prosecute traffickers ensures the safety of every community and every individual.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Human trafficking happens in our own communities and neighborhoods. This means each of us can make a difference by taking action to protect our communities. Here are some steps you can take to join the fight against human trafficking:

Measure: Find out what your state and district are doing about human trafficking.

- Do you know how prevalent trafficking is in your community or state?

- What are your state’s anti-trafficking laws?

- Is there a coalition or task force, or does one need to be formed?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Who are the members of task forces or coalitions in your state? Search the Office for Victims of Crime map.

- What steps has your state’s attorney general taken?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement.

- Engage with coalition members at the local, state, and national level.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with law enforcement, first responders, faith-based organizations, local hospitals, community organizations

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, [email protected], for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policy makers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Be a conscientious consumer – the National Center on Sexual Exploitation’s Dirty Dozen list exposing companies that perpetuate sexual exploitation is a good place to start.

- Urge local businesses to prevent trafficking in their supply chains

- Think about your own workplace and schools, and encourage the implementation of anti-trafficking protocols or victim-centered business practices.

- Volunteer with your local anti-trafficking organizations, or conduct awareness campaigns by partnering with local school districts, PTAs, city councils, or other community organizations such as Rotary clubs.

- Create a new coalition or partnership with an existing organization with the Office for Victims of Crime’s Human Trafficking Task Force e-Guide. Then, consider:

- Regular conferences, panel discussions, and workshops

- Certification and training, such as the International Anti-human trafficking certification program (iACT)

- Mentoring victims and survivors

- Engaging local and state chambers of commerce or legislators to be advocacy partners, or prepare a team to advocate for safety and protective measures in your community or state.

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.

For more ideas and ways to get involved, see the State Department’s 20 Ways You Can Help Fight Human Trafficking, the Department of Health and Human Services’s 10 Ways You Can Help End Human Trafficking, and The Policy Circle Discussion Guide for this brief.

Thought Leaders and Additional Resources

- The Department of Health and Human Services and its Human Trafficking Leadership Academy

- Senators Rob Portman (OH) and Richard Blumenthal (CT), Co-Chairs of the Senate Caucus to End Human Trafficking

- The Global Center Women and Justice’s Ending Human Trafficking Podcast

- Polaris Project and the National Human Trafficking Hotline referral directory and other resources

- Safe Coalition for Human Rights

- A21– An organization combatting human trafficking and modern-day slavery

Sex Trafficking

- The National Center on Sexual Exploitation

- Fight the New Drug

- Stop Trafficking Demand

- World Without Exploitation

Labor Trafficking

Child Exploitation

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.