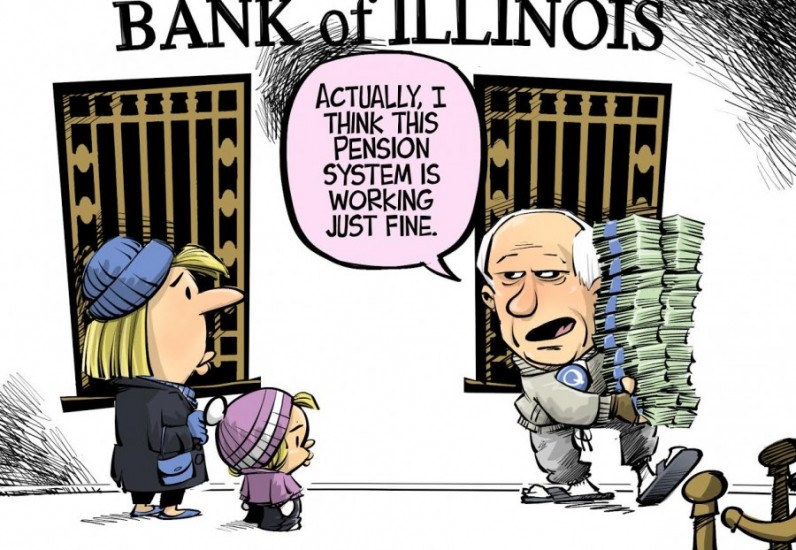

The state of Illinois is suffering from a government-worker pension shortfall of over $111 billion – the worst retirement crisis in the nation. Government-worker pension costs are overwhelming the state’s budget: 19 percent of the budget is going to pay for pensions, compared to 4 percent in other states. Illinois' overall pension debt is 268 percent higher than its annual revenue, the worst ratio in the nation. So, what exactly are government-worker pensions, and how did Illinois get to this point?

Big Picture

The following brief was prepared by Illinois Policy Institute.

The state of Illinois is suffering from a government-worker pension shortfall of over $111 billion – the worst retirement crisis in the nation. Government-worker pension costs are overwhelming the state’s budget: 19 percent of the budget is going to pay for pensions, compared to 4 percent in other states. Illinois’ overall pension debt is 268 percent higher than its annual revenue, the worst ratio in the nation. And Illinois has the lowest credit rating of any state – three notches above junk status.

Currently, the state has no official budget. Illinois politicians are arguing over what to do about a $4 billion deficit that’s due mainly to growing pension costs.

However, the pension problem is not just at the state level. Chicago has a multibillion-dollar government-worker pension shortfall and a junk credit rating of its own.

Hundreds of municipalities across Illinois are also struggling with their own pension crises. Cities are cutting services and raising taxes to pay for pensions even as their local pension funds fall deeper into insolvency.

So, what exactly are government-worker pensions, and how did Illinois get to this point?

What are pensions?

A government-worker pension in Illinois is a defined-benefit, or DB, retirement plan under which employees are guaranteed set annual benefits during retirement. In general, a DB plan works by having an employee and his or her employer contribute a set percentage of the employee’s salary to a pension fund over the course of the employee’s career. The fund invests those amounts, which are expected to grow enough to meet the fund’s future pension obligations. Importantly, the employee does not own or control an individual retirement account within the fund.

In exchange, the pension fund provides a guaranteed amount of money every year to the employee for life once he or she retires. In addition, the amount a retiree receives increases each year under an annual cost-of-living adjustment, or COLA.

There is a problem with DB plans

There is a problem with DB plans

The problem is, under a DB plan, what an employee is guaranteed in retirement has little relation to what the employee actually puts in. The employee’s pension benefits are based on his or her final salary, which is often spiked at the end of a career, not on how much the employee actually contributed over his or her career. That means an employee earns far more in benefits than the employee ever contributed. The difference has to be made up by the employer – which, in the case of Illinois’ government-worker pension funds, is Illinois taxpayers.

In addition, if the pension fund does not meet its expected investment returns, which is necessary to ensure the fund has enough money to make its future payouts, the employer (Illinois taxpayers) also must make up the difference.

In summary, if there is not enough money in government-worker pension funds – for whatever reason – it’s the taxpayer who must bail them out. By 2045, taxpayers will be paying $16 billion into the state’s pension funds, over 4.5 times more than what state employees will be expected to contribute.

What about defined-contribution or DC plans?

In contrast, in a defined-contribution, or DC, plan such as a 401(k) plan, both the employer and the employee contribute directly into a retirement account owned and controlled by the employee. The amount accumulated by the employee during his or her career becomes the pool of funds he or she will use for retirement. Once the employee retires, the employer has no future obligation.

Today, nearly 85 percent of private-sector employees are enrolled in some form of DC plan. The public sector, on the other hand, continues to rely largely on DB plans.

That said, more and more states, most recently Oklahoma, are moving their workers onto some form of DC plan in an attempt to get their budgets under control and give workers more power over their retirements.

The scope of the problem

Illinois has 675 government-worker pension funds that are supposed to provide retirement security for more than 1 million government workers and retirees.

There are five state-run funds for downstate and suburban teachers; state employees; state-university employees; judges and Illinois lawmakers.

In addition to those five state-run funds, there are 359 suburban and downstate police pension funds, 301 suburban and downstate firefighter pension funds, a pension fund for suburban and downstate municipal workers, six pension funds in Chicago and three pension funds in Cook County.

Each one of these groups – the state, Chicago and other municipalities – is in crisis.

Why Illinois has a crisis?

Illinois’ massive, growing government-worker pension debt is a direct result of a number of factors.

1. Politicians have offered generous pension benefits to government workers.

Politicians have granted state workers generous pension benefits that the state – and taxpayers – cannot afford. Over 63 percent of state workers retire before age 60. Most retirees receive annual 3 percent compounded boosts to their pensions, far above the rate of inflation, which allows their annual benefits to double in just 25 years.

At the same time, state workers don’t have to contribute very much to their own pensions. Most retirees end up contributing only about 6 to 8 percent (12 to 16 percent when interest earned on investments is included) of what they receive in retirement benefits.

Employees for the City of Chicago also receive generous pension benefits. Nearly half of all city workers retire before age 60, and retired career workers receive $65,000 average annual pensions.

At the state level, some government retirees receive over $2 million dollars over the course of their retirements. A worker in the private sector would need to have more than $1 million in the bank when he or she retires to receive similar benefits.

2. Politicians have failed to properly fund pensions

In 1994, Gov. Jim Edgar created a culture of kicking the can down the road when he enacted legislation that pushed government-worker pension payments far into the future – through 2045. Since then, Illinois politicians have borrowed (Gov. Rod Blagojevich, $10 billion; Gov. Pat Quinn, $7 billion) and taxed to fund pensions, rather than seek comprehensive reforms.

Politicians have also underfunded the state’s government-worker pension funds through stunts such as the 2006 pension holiday that diverted $2.3 billion in state contributions away from pensions.

The current state of the Chicago teachers’ pension fund is the best example of how pensions are manipulated and ruined by politicians. Over the course of a decade, Chicago politicians redirected $3 billion in contributions away from the teachers’ pension fund and toward teachers’ salaries instead. Not only did this cause the teachers’ pension shortfall to skyrocket (growing from zero in 1999 to over $9.5 billion by 2014), but it raised teachers’ pension benefits to unaffordable levels as well. That made the fund’s financial situation grow even worse.

The same thing also happened to Chicago’s police and firefighter pension funds. Police and firefighter salaries have grown 50 to 70 percentage points faster than inflation over the past 30 years, resulting in underfunded pension funds and increased pension benefits that Chicago taxpayers cannot afford.

3. The inherent flaws of pension plans have increased costs

In DB plans, governments make promises to retirees based on certain assumptions – such as expected investment returns and mortality rates – which often fail. And when those assumptions do fail, such as when funds fail to achieve their expected investment returns, the result is an underfunded pension system. Sixty percent of the state’s current pension shortfall can be attributed to such failed assumptions.

The combination of these three factors has driven Illinois’ pension systems closer and closer to insolvency. Only 16 percent funded, the General Assembly’s own retirement system is the worst-off, relying on a taxpayer bailout every year just to stay solvent.

But other government-worker pension funds are not far behind. Chicago’s police and firefighters’ pension funds have less than a third of the money they need to pay out future benefits.

Pensions and the Illinois Budget

As Illinois’ pension funds fall further into insolvency, the money needed to keep the funds afloat is growing far faster than Illinois’ budget.

Pension costs already make up 19 percent of Illinois’ budget – a massive amount when you consider that the average for other states is only 4 percent.

Those costs have been crowding out funding for the state’s vital services. And the crowding-out will only get worse unless serious reforms reducing the costs of pensions are enacted.

For example, teachers’ pension costs are already absorbing 90 percent of new state education dollars. By 2025, the state will spend more on teacher pensions than it will on classroom learning. This will drastically affect local school districts’ operational budgets – especially poorer districts with minority students that rely heavily on state funding.

What the other side says

Government-worker unions, in their defense of the status quo, often argue that the average benefits workers receive are modest. For example, the Chicago Teacher’s Union claims on its website that “the average Chicago Teachers’ Pension Fund (CTPF) retiree earns $42,000 per year.”

But that’s a misleading number. Average pension benefits are one of the most commonly used, but unhelpful, pension statistics. That’s because averages include both older retirees who’ve been retired for a long time and short-term workers who receive relatively small pensions for their limited time working for the government.

A more appropriate way to measure pension benefits is to look at the annual pensions of career (30-year) workers who retired recently (in the last three years).

In Chicago Public Schools, the average annual pension for a recently retired career teacher is $71,717 – a full $24,000 more than the average for all Chicago teachers. It’s also more than four times the average annual Social Security benefit that private-sector retirees receive ($16,000).

Unions also argue that pension benefits are a promise. Citing the Illinois Constitution’s pension-protection clause that states pensions may not be “diminished or impaired,” union officials say pension benefits for current government workers cannot be reformed.

It’s true that pension benefits that workers have already earned are protected. However, the Illinois Policy Institute believes that pension benefits going forward – those that workers haven’t earned yet – can be reformed in order to reduce the financial burden on Illinois’ governments.

To be clear, government workers who earn generous pension benefits have done nothing wrong. They benefit from labor negotiations that have led to lucrative compensation packages. But as Illinois governments at every level continue their slide into financial crisis, it’s clear that taxpayers can no longer afford to offer such benefits going forward.

The Illinois Policy Institute’s past reform proposals

The Institute has long been an advocate of moving all government workers to 401(k)-style retirement plans. In 2013, the Institute proposed a landmark bill that would pay government workers everything they’ve earned so far in the pension system and start a 401(k)-style system – modeled on the self-managed plans for state-university professors in which 18,000 employees are enrolled – for all benefits going forward.

The Institute also proposed a similar comprehensive pension- reform plan for the city of Chicago in 2014. The plan would have taken control of retirements away from politicians and put it in the hands of city workers. Going forward, all workers would own and control hybrid retirement plans with two key elements: a self-managed plan and a Social Security-like benefit.

Unfortunately, in May the Illinois Supreme Court adopted the government-worker unions’ point of view when it struck down Senate Bill 1 – a modest pension-reform law meant to bring some relief to Illinois’ fiscal crisis. The court ruled that the Illinois Constitution’s pension-protection clause protects both earned and unearned benefits of current state workers – ending any chance for significant pension reform involving current workers.

What we can do

Since the Supreme Court’s ruling on SB1, debate over how to fix Illinois’ pension crisis has come to a screeching halt. Most people shrug their shoulders and think there’s not much that can be done to fix Illinois’ broken government-worker pension system.

But there are still plenty of reforms that Illinois can undertake to lessen the cost of government-worker pensions and get itself on the right financial track.

Here is a list of what Illinois lawmakers can do immediately to address the state’s growing pension shortfall:

End politician pensions

The General Assembly’s pension plan is the most bankrupt of the five state-run pensions – it only has 16 cents for every dollar it should have today to meet its future obligations. With no unions to oppose reforms, Illinois politicians should lead by example and transition their own pensions into self-managed plans such as 401(k)s.

Offer 401(k)s for new workers

The Supreme Court’s ruling on SB1 doesn’t affect retirement plans for new government workers. Illinois lawmakers should follow the lead of states across the country – from to Michigan to Oklahoma to Alaska – and adopt self-managed plans for all new state and municipal workers.

Offer optional 401(k)s to current employees

Government workers shouldn’t be trapped in insolvent, politician-run retirement plans over which they have no ownership. It’s only fair that workers have the option to control their own retirement plans.

Require all teachers to make contributions toward their own pensions.

In Illinois, most public-school teachers don’t pay the required 9.4 percent employee contributions toward their own pensions. Instead, school districts pay, as a benefit, some or all of the teachers’ required payments. Eliminating teacher pension “pickups” could save Illinois school districts about $430 million annually.

Put pension costs where they belong

Currently, local school districts can get away with end-of-career salary spikes and other “sweeteners” that inflate future pensions because the actual pension costs of their employees are borne by the state – not the school district. The annual cost of teacher pension benefits – nearly $1 billion – should be shifted away from the state to local school districts, where it belongs.

Limit the growth of pensionable salaries

Government-worker pension benefits are growing at a pace that far exceeds the growth of taxpayers to fund them. With no way to reform current workers’ pension benefits, the only way to control costs is to limit salary growth and other items that drive up pensionable salaries.

Allow municipal bankruptcy.

Bankruptcy should be the option of last resort, but it can help struggling municipalities restructure their debt, renegotiate contracts and reform pensions.