The impact of sports in the United States is undeniable: sports teams have had lasting social and economic effects at the local level in their own communities and at the professional level across the country. What goes into the economic value of sports teams? What do sports bring to communities? What should the role be, if any, of government in fostering sports in community development?

Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

Professional sports teams have both united and divided cities, states, and entire regions of America. Back in 1876 the first professional sports league to form was the National League of Professional Baseball Clubs (today known as the National League), and was followed by many more professional leagues in the coming decades, including the National Hockey League in 1917 and the National Football League in 1922. Since then, professional sports teams have provided a much needed escape from daily life, and are a powerful social force. Consider the Chicago Cubs’ historic World Series win, Super Bowl parades for the Boston Patriots and the Philadelphia Eagles, or the intensity of the Yankees – Red Sox and Green Bay Packers – Chicago Bears rivalries.

Estimates show the sports industry generates around $70 billion annually in North America. That would place the sports industry in the top 50 on the Fortune 500 list, somewhere between PepsiCo and FedEx. In 2020, the NFL alone generated over $12 billion in revenue, a drop from $16 billion in revenue in 2019 due to COVID-19. The MLB generated about $10 million in revenue in 2019. In addition to television contracts, what else goes into the economic value of sports teams? What do sports bring to communities? What should the role be, if any, of government in fostering sports in community development?

Tax Status of Sports Teams

Tax Exemption

Professional

Sports teams themselves are taxable entities, but sport organizations such as the NHL, MLB, and NFL have a different history. Many of these organizations’ league offices, which handle the administrative functions of a sport, qualify as tax-exempt. During the summer of 2018, the Senate introduced the Properly Reducing Overexemptions for Sports Act “to eliminate the nonprofit status for the league offices of professional sports organizations.” This bill to amend the tax code did not pass, but brought up a necessary question: “Should Congress eliminate the exemption for professional sports leagues?”

In 1966, the IRS grouped football leagues with trade associations under section 501(c)(6) because, like trade associations, the leagues “act on behalf of their members.” The NFL, however, dropped its tax-exempt status in 2015; the MLB did so in 2007; the NBA was never tax-exempt. The act was aimed to eliminate this tax provision for any organization, although it specifically named the NHL, PGA, and LPGA. The operations of these three leagues generate a combined $1 billion in total revenue, which would result in $100 million over ten years in government revenue if the organizations were no longer tax-exempt.

Local

Local community leagues are often tax exempt. Reg. 1.501(c)(4) of the IRS tax code states that “social and recreational activities are not social welfare activities,” by default, but “an organization that stimulates the interest of youth in the community in organized sports” may qualify for tax exempt status if admission is “virtually free” and members’ attendance is encouraged. Amateur sports organizations may qualify for IRC501(c)(3) exemption if they are educational, charitable, and “conduct national or international competition in sports” or “support and develop amateur athletes for national or international competition in sports.” Little League Baseball, for example, has a group exemption number to which leagues can apply for federal tax exemption; state tax exemption would be a separate application.

Subsidies

Tax exemptions for sports leagues are only one small piece of the economic discussion surrounding sports teams. Directing public funds to fund sports venues is another point. Prior to the 1950s, almost all stadiums, such as Madison Square Garden and Wrigley Field, were built with private funds. Today, using public money to build a new stadium is now “common practice.” The Raiders received almost $750 million in subsidies to move from Oakland to Las Vegas. The stadiums for the Orlando Magic, Brooklyn Nets, and Dallas Cowboys also relied on public financing.

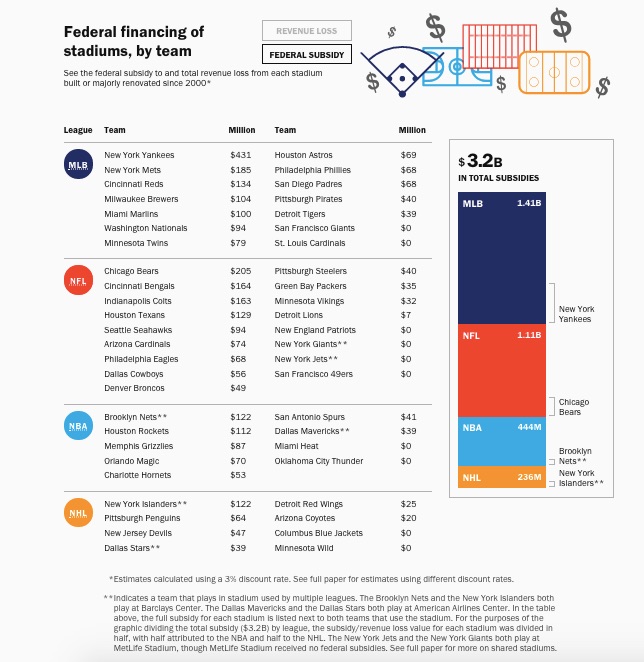

In New York in 2009, the final bill for the new Yankee Stadium came to $2.5 billion, about $1.7 billion of which came from tax-exempt municipal bonds issued by New York City. According to a Brookings Institution report, “Interest earned on the municipal bonds is exempt from federal taxes,” and so the $431 million in tax revenue that would have been collected if the bonds were taxable went instead toward constructing the stadium. Since 2000, the federal government has subsidized construction and renovations for 35 professional sports stadiums with $3.2 billion in federal taxpayer dollars.

So how does the government determine whether to award tax breaks and public financing for a sports organization? The U.S. “has grappled with determining the appropriate level of public versus private provision of infrastructure.” Usually, the federal government supports infrastructure by directly spending money or by making grants to state and local governments. In the realm of sports, public funding became the norm after the Boston Braves moved to Milwaukee to play in a stadium built with public funds in 1953. Congress attempted to stop the practice with the Tax Reform Act of 1986 (TRA86), which may have done more harm than good .

TRA86 tried to get rid of “the tax exemption for bonds financing sports stadiums by eliminating it from the category of private activity bonds exempt from federal taxation.” It did so by only granting federal tax exemption “if the state or local government is willing to finance at least 90 percent of the debt service for the bonds.” The measure backfired and instead became an incentive for local governments to finance the majority of a stadium project. Another stipulation required the financing to rely on “tax revenue unrelated to the stadium,” such as sales, property, or income taxes.

The Joint Committee on Taxation (2005) and the Obama administration’s 2015 and 2016 budgets proposed eliminating the tax exemption, and in 2017, Senators Cory Booker (D-NJ) and James Lankford (R-OK) co-sponsored a bill to end the tax exemptions. One public poll even demonstrated that over two-thirds of people oppose stadium subsidies. As part of a billion dollar industry, do sports teams need government handouts, or tax breaks on those handouts? No efforts have successfully ended the practice, but a bill to end stadium subsidies was reintroduced in February 2022.

The Impact of Teams on Neighborhoods

Economic

Government subsidies, particularly local subsidies, for a stadium are usually justified by “the economic impact it will have on the community.” Proponents generally cite construction projects that generate jobs, consumer spending (such as paying for parking or eating at restaurants near the new venue), new developments (such as new eateries or living spaces constructed as interest and property values grow), and economic development in underdeveloped areas.

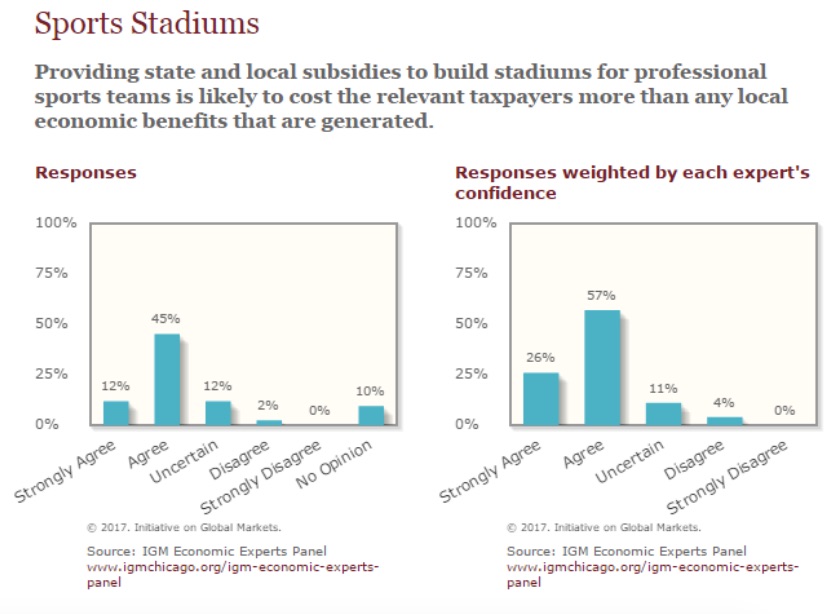

Since the 1990s, economic studies that examine the effects of stadiums have often found the “[b]enefits generated by professional sports facilities and franchises are smaller than the cost of the subsidies.” Dennis Coates, an economist from the University of Maryland, is the author of a 2015 study that found sports franchises “had no significant effect on the growth rate of per capita personal income.”

Another study by economists Roger Noll and Andrew Zimbalist that reviewed stadium investments came to the same conclusion, and added that since consumers usually have limited entertainment budgets, “dollars spent at a new stadium would not be new spending but rather diverted spending.” A study from the University of New Hampshire’s Scholars Repository added that this limited local economic impact remained regardless of a team’s success. Many argue that, given the lack of evidence for local benefits, there is little justification for federal subsidies. Economists tend to agree that such government interference in how the sports industry engages in the market in most cases does not have effects on communities that justify tax-payer investments.

Social

Some sports teams and their neighborhoods have adversarial relationships. The podcast 99% Invisible shares as an example the story of the development of Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles, the third oldest ballpark in the United States and “a civic institution, beloved by people throughout the city.” Originally an attempt to provide Los Angeles with something “that people could identify with or rally around” in the 1950s, Dodger Stadium displaced the neighborhood of Chavez Ravine, and will always be at least in part “a monument to the displacement of an entire community.”

Similarly, in Atlanta, Georgia, the $1.5 billion Mercedes-Benz Stadium sits right next to English Avenue and Vine City, two of the poorest neighborhoods in the southeastern U.S. Increasing property values due to the stadium development has many residents afraid of gentrification. The Atlanta Falcons’ stadium is “an uncomfortable reminder of the disconnect between the vast wealth of the NFL and the cities to which they extend open palms.”

At the same time, teams and owners do not sit on the sidelines, and foster positive relationships in their communities. Today, the Dodgers are largely engaged with the Los Angeles community, joining with local schools for education initiatives such as Read Across America and “Days of Service and Play.” Arthur M. Blank, Falcons team owner and co-founder of Home Depot, has encouraged the team’s sponsors to strengthen ties with the Atlanta community. Additionally, the Arthur M. Blank Family Foundation has donated $20 million towards job training, new parks, a youth leadership program, and homes for police officers in the neighborhoods near the stadium.

Since 2016, the Milwaukee Bucks have partnered with local Cousins Subs and have collected more than 14,000 pounds of food and donated over $50,000 for emergency food supplies to pantries around Wisconsin. The Miami Heat Charitable Fund supports programs that benefit at-risk families in South Florida, including domestic violence shelters, and provides educational scholarships. The San Francisco Giants sponsor community programs including Junior Giants, “a free, non-competitive and coed baseball program for youth ages 5-18.”

Professional sports teams from across the country are some of the many members of the Green Sports Alliance, a worldwide union of sports teams and venues that promote innovative strategies that benefit the environment and local community; for example, paper products used at the Diamondbacks’ Chase Field are made from recycled material, and any unused food is donated to the Phoenix community. In Florida, Jeff Vinik, owner of the Tampa Bay Lightning, reached out to the community to hear what people needed most. The Lightning Community Hero program has since allowed the team to help the community and get fans involved.

The Chicago Cubs Community Affairs team participated in nearly 100 meetings of community organizations and served on multiple boards of directors of neighborhood associations, chambers of commerce, and nonprofit groups. Throughout the year, Cubs players and coaches visit hospitals and schools and take part in on-field clinics for charitable organizations. In 2018, Cubs front office associates, coaches, and players dedicated 3,800 hours to community initiatives.

Community Development

In addition to community outreach, teams and owners readily invest in their neighborhoods. Vivek Ranadivé, owner of the Sacramento Kings, partnered with the city of Sacramento to replace the empty downtown mall with the King’s new arena in addition to a 1-million-square-foot commons. According to an economic development group for the city, downtown jobs have increased by almost 40% and at least 50 stores were set to open in the new area. Similar endeavors in mixed-use developments that partner sports franchises with residential and commercial spaces for public use have also been constructed in Columbus and San Francisco.

Without such mixed development, Stanford economist Roger Noll says the challenge is that supersized stadiums are difficult to incorporate into the community. Small, multi-use facilities “that are embedded in larger commercial and residential projects” can fit that bill. In Detroit, the Henry Ford Health Detroit Pistons Performance Center includes a walk-in sports medicine clinic as well as a small grocery store and cafe. Lambeau Field in Green Bay is usable year-round, services several youth sports teams, and serves not only for tailgating but also as a sledding hill, a skating rink, and a brewery. In addition, there are numerous examples where festivals and events held at sports facilities generate economic activity for the neighborhood and tax revenues. Music concerts held at Chicago’s Wrigley Field in 2018 generated more than $3.4 million in amusement taxes that went directly to the City of Chicago and Cook County.

Local initiatives to have stadiums and sports teams do their part are also gaining momentum. Nashville, Tennessee only agreed to the construction of a MLS stadium after the team signed a community benefits agreement (CBA), which included building affordable and workforce housing as well as a daycare near the stadium. A community committee oversees the terms of the agreement. In New York, developers turned an old, abandoned armory into the Kingsbridge National Ice Center after agreeing to a CBA that would provide the community access to the ice center, hire and train local employees, construct new schools in the surrounding area, and foster ongoing community involvement and dialogue. When properly executed, a CBA can be a “model for community coalition involvement.”

Conclusion

Sports teams can provide value, foster positive relationships with the local community, and provide a valued entertainment option. America has a sustained appetite for the industry, which is only projected to continue its growth. The right mix of public and private investment tends to be a local issue, but it can extend into the federal government and spark debate as to how private sports teams are held accountable to the families in their neighborhoods.

Additional Resources

Brookings Institution: Tax-Exempt Municipal Bonds and the Financing of Professional Sports Stadiums

Manhattan Institute: Stadium Subsidies Thriving in Sports Season

Mercatus: Congress Fumbles Tax Fix to Stadium Subsidies

Mercatus: Growth Effects of Sports Franchises, Stadiums, and Arenas: 15 Years Later

St. Louis Fed: The Economics of Subsidizing Sports Stadiums

Tax Foundation: Should Congress Reconsider the Tax Exemption of Pro Sports Organizations?

The Economic Effects of Successful Sports Franchises on Local Economies

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Find out what your state and district are doing about sports teams and subsidies or tax credits.

- Do you know the state of community engagement from sports teams in your area?

- You can search on sports’ teams websites. Look for a dropdown menu titled “community.”

- Are there recent development initiatives that may have started due in part to the presence of sports teams?

- Search “economic development,” or “community development” in the search bar on your municipality’s website.

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Make a list with contact information for the groups, committees, and departments involved.

- On your state or municipality website, look for a “government” or “departments” drop-down tab to learn more about your elected officials. See who is on boards such as an economic development board, zoning board, or a township committee.

- What steps have your state’s or community’s elected and appointed officials taken to enhance transparency and accountability regarding economic subsidies?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Reach out to talk to the people responsible for the initiative and the process. You have the right to know how dollars are spent, what the measures of success are, which contractors have been hired, and how the selection process works.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with community organizations, school boards, and local businesses.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, [email protected], for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policy makers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Consider asking your local business owners or your local Chamber of Commerce about economic effects and development due to the presence of sports teams. You can find your local one here.

- Contact local and community youth sports teams, and find out from community members how they are involved in the community.

- Research the professional sports teams in your area, and whether economic development subsidies were involved in building stadiums.

- See how your state ranks in terms of economic development subsidies.

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.