Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

Case Study

In 2017, Pennsylvania high school student Brandi Levy posted a photo online and a caption with expletives after failing to win a promotion from the junior varsity to varsity cheerleading team. After being suspended from the team “for what was considered disruptive behavior,” she went to court, arguing “the school had no right to punish her for off-campus speech” and in doing so was violating her First Amendment rights.

A federal district court agreed with Levy, as did the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit. Four years later, in June 2021, the Supreme Court ruled in Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L. that Levy’s online rant was protected speech under the First Amendment. The court did recognize, based on precedent from Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969), that school administrators can punish student speech that occurs off campus or online if it disrupts classroom study or can be classified as harassment or bullying.

EducationWeek explains why this case gained traction and what the Supreme Court’s decision entails (4 min):

Why it Matters

U.S. law is based first and foremost on the U.S. Constitution. The judicial branch is expected to apply the law impartially and without regard for politics (being in this way independent), but while still taking responsibility for their decisions (being in this way accountable). The combination of independence and accountability makes the judicial branch unique, and helps maintain the balance of power with the legislative and executive branches.

In the U.S., the rule of law is the bedrock of our free society. Judges are the guardians of the rule of law and they should apply the law in a competent, efficient, and impartial manner. This proper functioning of the judiciary is essential to building trust in American society. Americans interact with the judicial branch on a regular basis. Article III of the Constitution “guarantees that every person accused of wrongdoing has the right to a fair trial before a competent judge and a jury of one’s peers.” Understanding how the court system works is key to understanding our own roles – and rights – as citizens.

Putting it in Context

Background

The framers of the Constitution knew the federal government needed courts to help enforce its law. If the courts were left entirely to the states that were suspicious of centralized power, it would be difficult for the new federal government to manage them. At the same time, citizens’ main loyalty was to their states, and the federal government was far enough away that an extensive system of federal courts without connections to state governments could breed mistrust.

The compromise became Article III of the U.S. Constitution, which establishes the judicial branch with two different systems, one Federal System and one State System. At the federal level is the Supreme Court and other federal courts, which are established by Congress. The courts decide the constitutionality of federal laws and resolve other disputes regarding federal laws.

At the state level, Article III gives states the independence to create their own rules about courts’ jurisdiction, judicial selection, and scope of judicial power. Although the Supreme Court draws a lot of attention to the federal system, the state systems do much more work and are far larger.

Today, the U.S. court system at both the federal and state level has three tiers:

- trial courts,

- courts of appeals (or appellate courts), and

- a high court, or Supreme Court.

Overview of the Courts

Federal

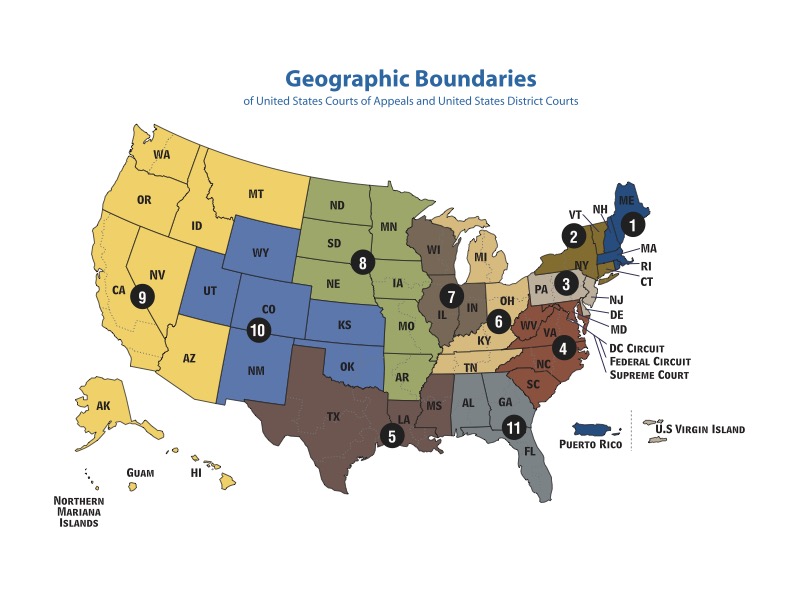

The entire federal court system consists of 94 district level trial courts that are organized into 12 regional circuits (11 regions and the D.C. circuit, see the map below).

Trial courts “resolve disputes by determining the facts and applying legal principles to decide who is right.” The district judge tries the case, and the jury decides the case. There is at least one district court in each state and the District of Columbia.

There are also two special federal trial courts:

- The Court of International Trade, which addresses cases involving international trade and customs laws;

- The Court of Federal Claims, which deals with claims for money damages against the U.S. government.

Bankruptcy courts are also units of the federal district courts. There are 90 U.S. bankruptcy courts. Bankruptcy cases cannot be filed in state court; the federal courts “have exclusive jurisdiction over bankruptcy cases involving personal, business, or farm bankruptcy.” The process allows individuals who can no longer pay their creditors to seek a court-supervised liquidation of assets, or to reorganize their financial affairs to pay the debts.

Each of the 12 regional circuits has its own court of appeals. Including the court of appeals in the Federal Circuit, there are a total of 13 appellate courts below the Supreme Court. This is where the losing side goes if they are unhappy with the result of a case in trial court. Appellate courts do not decide factual disputes, but only determine whether the law was applied to those facts correctly by the trial judge. A panel of three judges usually makes decisions in appellate courts, and there is no jury. The highest court of appeals, and the highest U.S. court, is the Supreme Court.

Article I Courts

Beyond the thirteen appellate courts, a few courts were established to deal with appeals on specific subjects. These Article I Courts were created by Congress as legislative courts that do not have full judicial power. They are:

- The U.S. Court of Appeals for Veterans Claims, which has “exclusive jurisdiction over decisions of the Board of Veterans’ Appeals… The Court reviews Board decisions appealed by claimants who believe the Board erred in its decision.”

- The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Armed Forces, which “exercises worldwide appellate jurisdiction over members of the armed forces on active duty and other persons subject to the Uniform Code of Military Justice.” Decisions are subject to direct review by the Supreme Court.

- The U.S. Tax Court, which settles disputes between taxpayers and the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and “ensures a uniform interpretation of the Internal Revenue Code.” It serves as one of the courts “in which taxpayers can bring suit to contest IRS determinations.”

Supreme Court

The Supreme Court is “the final judicial arbiter” on matters of federal law (referring to the Constitution and laws passed by Congress), which means lower courts follow the precedent set by Supreme Court decisions.

The Supreme Court is “the final judicial arbiter” on matters of federal law (referring to the Constitution and laws passed by Congress), which means lower courts follow the precedent set by Supreme Court decisions.

Justices also consider appeals from the highest courts at the state level, or from appellate courts at the federal level. After a case is tried, it may be appealed to a higher court (a court of appeals). Usually, this court has the final word, but a litigant who loses in a federal court of appeals or the highest court of a state, “may file a petition for a ‘writ of certiorari,’ which is a document asking the Supreme Court to review the case.” The Supreme Court gets 7,000-8,000 requests for certiorari per term, but usually grants fewer than 100. For cases not selected by the Supreme Court, the decision of the court of appeals stands. Justices also do not issue advisory opinions, meaning they do not weigh in on laws or the legality of actions unless a case is brought before the judiciary.

Judge Douglas Ginsburg explains how a case reaches the Supreme Court (3 min):

By law, the Supreme Court term begins on the first Monday in October. The Court hears oral arguments from October through April. Typically, the Court is in recess from late June or early July until the start of the next term in October.

The Federalist Society project, A Seat at the Sitting, features constitutional experts breaking down the Supreme Court’s upcoming cases and oral arguments from the previous month. See landmark Supreme Court cases here, from the American Bar Association.

Number of Justices

The first Judiciary Act, passed in 1789, set six Supreme Court justices. Over the next few decades, the Court has had as few as 5 and as many as 10 justices. The Judiciary Act of 1869 fixed the number of justices at nine, and has not been changed since. A quorum of six Justices is required to decide a case, although Justices are allowed to participate retroactively by listening to recordings or reading transcripts of arguments.

CNBC takes a look at what it’s like to be on the Supreme Court (4 min):

State

A state court is a court that has general jurisdiction within a specific state’s territory. State courts are the final arbiters of the state’s constitution and statutes. Based on Article III of the U.S. Constitution, states establish the structure of their own courts.

Over 95% of legal cases are handled by state courts, such as business disputes, traffic offenses, divorce, wills and estates, buying, and selling property.

Each state has its own court system that mirrors the federal system in terms of trial courts and appellate courts. Appellate courts include a “court of last resort,” usually called a supreme court, in each state. The exact makeup of these systems varies by state. For example, Texas and Oklahoma both have two courts of last resort, one for criminal cases and one for civil cases. Other states have “limited jurisdiction” trial courts, so there are different courts to hear cases revolving around different areas of law, as well as municipal and county courts on the local level.

See your state’s courts and judges with Ballotpedia’s map.

Crash Course Government and Politics breaks down the U.S. Court System (7 min):

Selecting Judges

Federal Judges

Nomination

Nomination

Any candidate for federal judgeships, whether it is for a federal district court or the Supreme Court, must be nominated by the President and confirmed by the Senate. Quite often, the President accepts advice from the Senate when considering nominees. Home-state senators are very active in suggesting possible nominees for vacancies in their states; senators in almost half of the states rely on commissions to screen potential candidates and submit recommendations to the White House. White House Staff and the Department of Justice often review the recommended nominees.

Evaluation

When the President submits a nomination to the Senate, the nominee is subject to pre-hearing evaluations. This includes an evaluation by the American Bar Association’s Standing Committee on the Federal Judiciary. Additionally, the Justice Department and White House aides conduct investigations of the nominee’s public record and professional credentials, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation investigates the nominee’s financial affairs.

Senate Judiciary Committee Hearing

After evaluations, the nominee must testify in a hearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee. Questioning usually focuses on the nominee’s legal qualifications, biographical background, past rulings, and the constitutional values and ideology. This public hearing also includes witnesses, often professional colleagues and the chair of the American Bar Association Committee.

After the hearing, the Judiciary Committee makes a recommendation on the nominee to the full Senate. The Committee can:

- Report the nomination favorably (with support levels included, explaining unanimity, party-line opposition);

- Report the nomination negatively;

- Make no recommendation.

The recommendation is symbolic, but still very important: “A report with a negative recommendation or no recommendation permits a nomination to go forward, while alerting the Senate that a substantial number of committee members have reservations about the nomination.”

Full Senate Vote

Once the question of confirming the nominee is brought to the full Senate, there is no limit for how long floor consideration may last. The remarks on the floor usually focus on professional qualifications, judicial philosophy, ideology, Constitutional values, and, particularly in recent decades, the impact on the Court’s “perceived ideological ‘balance[.]’” After floor debate, the confirmation is put to a vote, which requires a simple majority of Senators.

Once the question of confirming the nominee is brought to the full Senate, there is no limit for how long floor consideration may last. The remarks on the floor usually focus on professional qualifications, judicial philosophy, ideology, Constitutional values, and, particularly in recent decades, the impact on the Court’s “perceived ideological ‘balance[.]’” After floor debate, the confirmation is put to a vote, which requires a simple majority of Senators.

Tenure

Article III states that federal judges “‘shall hold their offices during good behavior, and shall, at stated times, receive for their services, a compensation, which shall not be diminished during their continuance in office.’”

This means that federal judges do not have fixed terms; they serve until death, retirement, or removal. Federal judges can only be removed through House impeachment and Senate conviction. Only 15 federal judges have been impeached by the House, and of those only 8 have been convicted and removed from office.

The goal of no fixed terms, and no campaigning, was to make the courts independent. Without the need to consider elections, judges “are thought to be insulated from political pressure when deciding cases.” Some criticize lifetime tenure, arguing that judges can hold their positions long enough to potentially become out of touch with the general public. However, making changes, such as the possibility of fixed terms, would require a Constitutional amendment.

State Judges

Each state has the authority to create its own fair and impartial judicial branch, which includes choosing a method of judicial selection and whether or not the judges serve fixed terms. There are five main methods of choosing judges across the states:

Each state has the authority to create its own fair and impartial judicial branch, which includes choosing a method of judicial selection and whether or not the judges serve fixed terms. There are five main methods of choosing judges across the states:

- Partisan elections, in which judges are elected by the people, with candidates listed on ballot alongside a label designating political party affiliation;

- Nonpartisan elections, in which judges are elected by people but candidates are listed on ballot without party affiliation label;

- Legislative elections, in which judges are selected by the state legislature;

- Gubernatorial appointment, by which judges are appointed by governor, sometimes with approval from a legislative body;

- Assisted appointment, also known as merit selection or the Missouri Plan, in which a nominating commission reviews qualifications of judicial candidates and submits a list of recommended candidates to the governor, who appoints a judge from the list. After an initial term, the judge is confirmed by the public in a retention election to remain on court.

Methods usually vary based on factors such as the type of court (trial vs appellate court) and whether this is the judge’s first term. In comparison to the argument against lifetime tenure, judicial selection methods such as elections are also “often criticized [because] judges might think they have to do politically popular things.”

In total, there are about 30,000 state judges. You can find who serves as a judge in your state courts, the judicial vacancies in your state, as well as your state’s methods for filling vacancies and qualifications for becoming a judge.

Below is a table from Ballotpedia that shows which method of selection is used in each state. Read The Policy Circle’s Deep Dive on Judicial Selection for more on qualifications, how potential judges are nominated, and pros and cons of different selection methods.

Checks and Balances

Article III of the Constitution establishes the Judicial Branch, but leaves Congress the power to determine the number of Justices and to establish courts inferior to the Supreme Court (district courts and courts of appeals). It also specifies the power of the President to appoint federal judges, with Senate Confirmation.

Congressional Committees

The House Judiciary Committee was established in 1813 “to consider legislation related to judicial matters,” and is the second oldest standing Congressional committee. Since its creation, the scope of its jurisdiction has expanded to include:

- Protecting Constitutional freedoms and civil liberties;

- Overseeing the U.S. Departments of Justice and Homeland Security; and

- Addressing legal and regulatory reform, competition and antitrust laws, terrorism and crime, immigration reform, and proposed amendments to the Constitution.

The House Judiciary Committee subcommittees include:

- Immigration and Citizenship;

- Crime, Terrorism, and Homeland Security;

- Courts, Intellectual Property, and the Internet;

- Constitution, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties; and

- Antitrust, Commercial, and Administrative Law.

See committee members and recent legislation at Govtrack.

The Senate Judiciary Committee, established in 1816, is one of the Senate’s original standing committees. It has oversight of key executive branch activities, and Department of Justice agencies including the Federal Bureau of Investigation and the Department of Homeland Security. It is also responsible for the initial stages of the confirmation process of all judicial nominations for the Federal judiciary, including positions for the Department of Justice, the Office of National Drug Control Policy, and select positions in the Departments of Homeland Security and Commerce.

The Senate Judiciary Committee subcommittees include:

- Antitrust, Competition Policy and Consumer Rights;

- Border Security and Immigration;

- The Constitution;

- Crime and Terrorism;

- Intellectual Property; and

- Oversight, Agency Action, Federal Rights and Federal Courts.

See committee members and recent legislation at Govtrack

Areas of Debate

Judicial Power

In The Federalist No. 78, Alexander Hamilton argued that the judiciary is the weakest of the three branches of government, as it does not have the power to enact legislation, as Congress does, or enforce laws, as the executive branch does. Others argue that the judicial power of the courts makes the judicial branch the most influential branch of government. Judicial power is the power to “interpret the Constitution, and strike down laws and official actions that are inconsistent with it,” regardless of whether Congress, the President, or state officials agree with that interpretation. Richard W. Garnett, Professor of Law at the University of Notre Dame Law School, argues that a branch of government “that gets to decide what other branches may or may not do, and that gets to overturn policy choices made by elected and accountable branches, hardly seems like ‘the weakest’.”

The ability of federal courts to overturn such policy choices is called judicial review, the idea “that the actions of the executive and legislative branches of government are subject to review and possible invalidation by the judiciary.” This power is not specifically granted in the Constitution, but “the power to declare laws unconstitutional has been deemed an implied power,” based on Articles III and IV of the Constitution. In the landmark case of Marbury v. Madison, the Supreme Court for the first time struck down an act of Congress as unconstitutional, thus setting the precedent.

The ability of federal courts to overturn such policy choices is called judicial review, the idea “that the actions of the executive and legislative branches of government are subject to review and possible invalidation by the judiciary.” This power is not specifically granted in the Constitution, but “the power to declare laws unconstitutional has been deemed an implied power,” based on Articles III and IV of the Constitution. In the landmark case of Marbury v. Madison, the Supreme Court for the first time struck down an act of Congress as unconstitutional, thus setting the precedent.

Judicial review covers Congressional legislation as well as executive and administrative orders. Its limit is that the courts can only review laws and acts that are challenged in court. Additionally, the court in and of itself does not have enforcement powers, but must rely on the other branches of government to enforce its decisions. For example, Congress has the power to withhold money for court-ordered actions and propose new laws that can override court decisions.

The Federalist Society explains how Judicial Review works (3 min):

Politicization

Given the power of judicial review, it is essential that the judicial branch be independent from the President, Congress, and politicization. However, “[p]olitical considerations typically play an important role in Supreme Court appointments.” According to Neal Devins of William & Mary Law School and Lawrence Baum of Ohio State University, since the 1990s “growing partisan polarization…has shaped the Court in multiple ways.” Even for federal trial and appellate courts, “[t]he Senate confirmation process too pays increasing attention to ideology, including party line votes that block the consideration of judicial nominees.”

Another aspect of Supreme Court politicization is the nature of the issues that have come before the Supreme Court in recent decades. Issues like abortion, gay marriage, and gun rights have all been the subject of major Supreme Court decisions, explains Andrew Breiner at the John W. Kluge Center at the Library of Congress. These decisions are “instituting new political realities in areas where Congress has found itself unable or unwilling to legislate. In this way, the court appears to legislate, eliciting anger or celebration from a public that sees justices as political allies or opponents.” Looking at this politicization, many have called to reform the Court.

TED-Ed explores the politicization of the Supreme Court Nomination Process (4 min):

Politicization is also a challenge at the state level, and is most often a subject of debate when it comes to methods of judicial selection. The following chart, adapted from Ballotpedia, breaks down the arguments:

Court Packing

Court packing means adding more Justices to the Supreme Court. The term comes from President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s case for adding more Justices to the Supreme Court in 1937. The Court had found some of Roosevelt’s New Deal economic recovery laws and programs unconstitutional, mostly in 5-4 decisions. The idea, however, never gained traction and was even opposed by Roosevelt’s own party.

The Constitution does not set the number of Justices for the Supreme Court, but rather gives Congress the power to determine the number of Justices. This means Congress can pass legislation to change the size of the Court, but long-standing precedent tends to hinder any changes. The Judiciary Act of 1789 established the first Supreme Court with six Justices. In 1807, Congress added a seventh federal court circuit and expanded the Court to seven Justices. When Congress created the Tenth Circuit in 1863, the Court was briefly expanded to ten Justices. In 1869, the Judiciary Act established nine Justices, and the number has not been changed since.

The Constitution does not set the number of Justices for the Supreme Court, but rather gives Congress the power to determine the number of Justices. This means Congress can pass legislation to change the size of the Court, but long-standing precedent tends to hinder any changes. The Judiciary Act of 1789 established the first Supreme Court with six Justices. In 1807, Congress added a seventh federal court circuit and expanded the Court to seven Justices. When Congress created the Tenth Circuit in 1863, the Court was briefly expanded to ten Justices. In 1869, the Judiciary Act established nine Justices, and the number has not been changed since.

University of Wyoming College of Law professor Stephen Feldman argues that expanding the court is constitutional, because Congress can change, and has changed, the makeup of the court in the past. He adds that the court’s decision-making process, as well as the nomination and confirmation process, has been politicized for a long time; while today’s polarization is more intense, there have been a number of political battles in the history of the courts.

Gettysburg College professor of political science Scott S. Boddery argues that a long-politicized history does not need to be made worse. He predicts, “Expanding the court would inevitably launch a spiral of escalation… and [exacerbate] the appearance of the court as a political tool.” Instead, he suggests allowing the number of judges to float. In this plan, each president would get to appoint one justice at some point in their first term, and another justice in their second term if re-elected. Vacancies due to death or retirement would not be directly filled, allowing for the fluctuating number. In the event that an even number of Justices leaves a decision in a deadlock, then the decision of the lower court would stand, so there would be no delegitimizing effect on the Court.

Gettysburg College professor of political science Scott S. Boddery argues that a long-politicized history does not need to be made worse. He predicts, “Expanding the court would inevitably launch a spiral of escalation… and [exacerbate] the appearance of the court as a political tool.” Instead, he suggests allowing the number of judges to float. In this plan, each president would get to appoint one justice at some point in their first term, and another justice in their second term if re-elected. Vacancies due to death or retirement would not be directly filled, allowing for the fluctuating number. In the event that an even number of Justices leaves a decision in a deadlock, then the decision of the lower court would stand, so there would be no delegitimizing effect on the Court.

According to Boddery, the underlying source of what erodes the Court’s legitimacy is the politicization of the nomination and confirmation process. He explains, “What this scenario would not have is the opportunity for one president to get to make more nominations than another, nor the opportunity for a justice to time their retirement to maximize the chances of an ideologically compatible successor, nor the opportunity for the Senate to hold open a vacancy until the next election to place such an explicit partisan referendum on the court.”

Conclusion

The judicial branch interprets and applies the law, ensuring the constitutionality of actions by the legislative and executive branches and thereby safeguarding the rights of American citizens. How much power the judicial branch has over the executive and legislative branches is up for debate, particularly in light of the politicization of the Supreme Court in recent decades. Calls for reform have generated little consensus, but understanding the structure and role of the court system in our lives can help us decide which reforms may ensure the independence of the judiciary.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Find out how your state and district approach judicial selection.

- Do you know the judicial vacancies in your state?

- What are your state’s methods for filling judicial vacancies?

- What are your state’s qualifications for becoming a judge?

- Where are your state’s courts and administrative offices?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement personnel, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Who serve as judges in your state’s or district’s courts?

- What role does the governor play? Is there a commission?

- If your state elects judges, when is the next election cycle?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Find people in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state who share your interest in the judicial selection process and the judicial branch. Is there a Federalist Society chapter in your community?

Plan: When are the judicial elections in your state, or appointments by the governor?

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, [email protected], for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policy makers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Explore your state’s court structure and who your state judges are with Ballotpedia’s Courts and Judges By State Map.

- Find out about federal district court judges in your state, as well as your state supreme court judges, appellate judges, trial court judges, and municipal judges.

- Determine whether your judges were appointed, and if so, by whom?

- See what, if any, judicial elections take place in your state with Ballotpedia’s Judicial Election Portal.

- Explore past judicial election results and see upcoming election information.

- Determine whether your judges were elected in partisan elections, and if so, to which party do they belong?

- See if there is room for your state or district to implement judicial evaluation plans, if it has not already.

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.

Additional Resources

- The Federalist Society

- State Courts Guide

- USA.gov

- US Senate Supreme Court nominations

- National Center for State Courts

- State Court Websites

- Court Structures by State

- Court Statistics Project

- Judgeship appointments since President Roosevelt

- Heritage Foundation: Judicial Appointment Tracker

- National Association of Counties County Explorer to find county or municipal courts

- Opinions of the Court: 2021

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.

Deep Dives

Want to dive deeper on The Judicial Branch? Consider exploring the following: