Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or of the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.”

– First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution

Why it Matters

Why it Matters

Cultural shifts have changed the way many view free speech, the proper debate of ideas, and the consequences of freedom of speech in the public square and online. Philanthropy Roundtable highlights two open letters published by separate academic groups addressing these concerns. Newsweek’s “Philadelphia Statement on Civil Discourse” notes, “Common decency and free speech are being dismantled through the stigmatizing practice of blacklisting ideological opponents” Similarly, Harper’s “A Letter on Justice and Open Debate” states, “It is now all too common to hear calls for swift and severe retribution in response to perceived transgressions of speech and thought.”

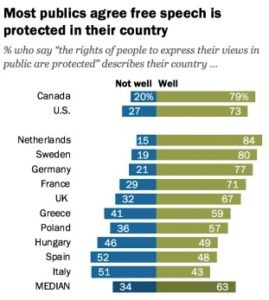

Freedom of expression is considered central to a vibrant democracy; Article 19 of the United Nation’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) says, “Everyone has the freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media regardless of frontier.” Silencing ideas that do not align with our own prevents “a flourishing, open marketplace of ideas” that underlies the exchange of ideas, self-determination, and freedom.

Putting it in Context

In part, the Founding Fathers intended the First Amendment to protect the rights of the American people and the press to express or publish opinions that are critical of the government. The First Amendment to the Constitution was passed by Congress on September 25, 1789, and ratified on December 15th, 1791.

According to ACLU’s The Bill of Rights: A Brief History: “The rights that the Constitution’s framers wanted to protect from government abuse were referred to in the Declaration of Independence as ‘unalienable rights.’ They were also called ‘natural’ rights, and to James Madison, they were ‘the great rights of mankind.’”

An individual’s right to free speech is the “most basic component of freedom of expression,” as described by Cornell University Law School. This portion of the First Amendment “allows individuals to express themselves without interference or constraint by the government. Regarding freedom of the press, “despite popular misunderstanding the right to freedom of the press guaranteed by the First Amendment is not very different from the right to freedom of speech. It allows an individual to express themselves through publication and dissemination. It is part of the constitutional protection of freedom of expression. It does not afford members of the media any special rights or privileges not afforded to citizens in general.”

The Founders saw the press as vital to the search and for attainment of truth, scientific progress, cultural development and as a check upon self-aggrandizing politicians. Still, the ACLU notes that “even the Constitution’s framers were guilty of overstepping the First Amendment,” particularly during times of national stress.

For example, the Alien and Sedition Act in 1798 (during the French and Indian War) limited what people could say against the government. In the 19th century, similar laws suppressed the speech of “abolitionists, religious minorities, suffragists, labor organizers, and pacifics.” During the early 20th century, “courts routinely granted injunctions prohibiting strikes” and “protestors opposing U.S. entry into World War I were jailed for expressing their opinions.” In 1923, Upton Sinclair was arrested for trying to read the First Amendment at a union rally.

A few court cases turned the tide of the crackdown on free speech. In 1919, the Supreme Court determined in Schenck v. U.S. and in Abrams v. U.S. that “speech could only be punished if it presented ‘a clear and present danger’ of imminent harm.” In Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), the standard was tightened: “Speech can be suppressed only if it is intended, and likely to produce, ‘imminent lawless action.’”

The Role of Government

Today, the role of government in free speech matters is limited primarily to protecting its citizens’ Constitutional rights, with interpretation of the First Amendment in specific cases left to the judiciary. According to the Constitution Center, “Although the First Amendment says ‘Congress,’ the Supreme Court has held that speakers are protected against all government agencies and officials: federal, state, and local, and legislative, executive, or judicial.” Without first satisfying “a variety of standards and tests that have been established by the Supreme Court over the past century,” the government is very limited in its ability to restrict free speech.

This is based on the idea that laws restricting the content of speech usually violate First Amendment rights because such laws “distort public debate and contradict a basic principle of self-governance: that the government cannot be trusted to decide what ideas or information ‘the people’ should be allowed to hear.” This applies to speaking, writing, printing, and broadcasting, as well as publications on the Internet, displays and demonstrations, and even clothing.

The same does not apply, however, to private individuals or organizations, such as private landowners, private employers, or private colleges. The University of Chicago Law School’s Geoffrey Stone explains, “Like all guarantees of the Bill of Rights, the First Amendment’s fundamental guarantee of ‘freedom of speech, and of the press’ limits only the actions of the government (federal, state and local), not the actions of private individuals, organizations or businesses.”

What the government can do is impose “time, place, and manner” restrictions, such as requiring permits for meetings. The government is also allowed to intervene when a protest “crosses the line from speech to action.” For the most part, however, freedom of speech is seen as necessary to self-government because it “gives the American people a ‘checking function’ against government excess and corruption.”

PolicyEd breaks down who can restrict free speech (1 min):

Challenges and Areas for Reform

The American Bar states that even two centuries after the Bill of Rights was ratified, “debate continues about the meaning of freedom of speech and its First Amendment companion, freedom of the press.”

Money and Politics

In recent decades, campaign contributions have been included as a form of free expression, but the question of whether and how the government can “constitutionally restrict political expenditures and contributions in order to ‘improve’ the democratic process” still remains. According to Geoffrey Stone of the University of Chicago Law School, after Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010) and McCutcheon v. Federal Election Commission (2014), “almost all government efforts to limit the impact of money in the political process have been held unconstitutional,” since these are considered as First Amendment rights of free expression. Still, some continue to argue that “the need to prevent what they see as the corruption and distortion of American politics caused by the excessive influence of a handful of very wealthy individuals and corporations is a sufficiently important government interest to justify limits.”

For more on money and politics, see The Policy Circle’s Campaign Finance Reform brief.

“Low” Value Speech

“Low” value speech, which includes defamation, obscenity, and threats, is not protected by the First Amendment. New York Times v. Sullivan (1964) determined that defamation is not protected when it damages a person’s reputation and was done intentionally with malice. Obscenity and child pornography are also not protected, based on rulings in Miller v. California (1973) and New York v. Ferber (1982), respectively.

Hate speech, “speech that expressly denigrates individuals on the basis of such characteristics as race, religion, gender, national origin, and sexual orientation,” however, is not subject to regulation and as it “does not constitute low value speech” based on past Supreme Court rulings. This is also the case for entertainment, vulgarity, blasphemy, and even violent video games, although there is an exception for discrimination. According to Professor Eugene Volokh of UCLA School of Law, “when speech is ‘severe or pervasive’ enough to create a ‘hostile or offensive environment’…such speech becomes a form of discrimination.”

PolicyEd discusses the limits of free speech (1 min):

Classified Information

In 1971, the Supreme Court ruled in New York Times v. United States (the Pentagon Papers case) that the government “cannot constitutionally prohibit the publication of classified information unless it can demonstrate that the publication or distribution of that information will cause a clear and present danger of grave harm to the national security.” There is an exception for government employees; in Snepp v. United States (1980), the Court ruled that employees who have access to classified information can be restricted from unauthorized disclosure of that information.

An open question is whether or not some government leakers are protected by the first amendment if they leak information “that discloses an unconstitutional, unlawful, or unwise classified program,” as is the case with Edward Snowden.

According to the ACLU, the Supreme Court has never actually sided with the government’s desire to keep some information secret, noting that “the government has historically overused the concept of ‘national security’ to shield itself from criticism, and to discourage public discussion of controversial policies or decisions.”

Cancel Culture

Dictionary.com defines cancel culture as, “the popular practice of withdrawing support for (canceling) public figures and companies after they have done or said something considered objectionable or offensive.” From journalists and editors to university professors and researchers, many have faced backlash or have even been ousted from positions based on thoughts, opinions, and sometimes past mistakes.

Many young Americans say it is important to hold others accountable for their words and actions; They tend to lean more towards the idea of a “call out,” when “someone does something wrong, people tell them, and they avoid doing it again in the future.” But calling out can go too far, and many Americans express, “in no uncertain terms, serious concern for cancel culture’s impact on society.”

Former president Obama weighs in on the cancel culture debate (2 min):

According to the “Philadelphia Statement on Civil Discourse,” social media mobs and cancel culture “foster conformism (‘group think’) and train us to respond to intellectual challenges with one or another form of censorship.” Harpers’ “A Letter on Justice and Open Debate,” agrees that there is “an intolerance of opposing views” and “a vogue for public shaming and ostracism.

Cancel culture results in the restriction of discourse, debate, and the exchange of ideas, “on which the health and flourishing of a democratic republic crucially depend,” the Philadelphia Statement says. Similarly, “A Letter on Justice and Open Debate likens “an intolerant society” to “a repressive government” in that both prevent democratic participation.

For a closer look at how cancel culture operates, read the NY Times’ Tales from the Teenage Cancel Culture.

On Campus

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969) that students “‘do not shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech and expression at the schoolhouse gate.'” In public schools, officials act as part of the government, and so must adhere to the Bill of Rights. However, courts have allowed school officials to prohibit certain types of student expression, namely speech that “substantially disrupts the school environment or invades the rights of others.” In recent years, given the age of social media, how schools should address potentially disruptive speech that originates off campus is another important question. For example, at least 25 states have laws that require schools to address off-campus cyberbullying. Even the Supreme Court has weighed in on student free speech rights.

Another component of the free speech debate on campuses surrounds college speech codes. In their 2015 essay, “The Coddling of the American Mind,” (which prefaced the book), Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt say that “in the name of emotional well-being, college students are increasingly demanding protection from words and ideas they don’t like.” This is not exactly new; in the 1980s and 1990s, calls for political correctness and anti-harassment codes on college campuses were followed by speech codes, “policies prohibiting speech that, outside the bounds of campus, would be protected by the First Amendment.” Some think that policing speech on campus is unconstitutional – restrictions on speech by public schools can amount to government censorship – while others argue such restrictions are necessary to deter hate speech. Although many college speech codes have since been dismantled or defeated in court – they do still exist. Speech codes can be “attractive to college administrators as a quick fix to address campus tensions.”

Similarly, whether schools should prohibit speeches by “speakers whose messages are offensive to student groups” is another area of debate. According to the ACLU, such restrictions “deprive students of their right to invite speech they wish to hear, debate speech with which they disagree, and protest speech they find bigoted or offensive.” First Amendment rights group FIRE (Foundation for Individual Rights in Education) maintains a “Disinvitation Database” of cases from 2000 to present where school administrators have rescinded invitations they have sent to speakers, usually due to pressure from students and/or faculty members.

The University of Chicago was one of the first higher education institutions to directly address free speech on campus, publishing the “Chicago Statement” in January of 2015. The statement maintains that “it is not the proper role of the University to attempt to shield individuals from ideas and opinions they find unwelcome, disagreeable, or even deeply offensive,” and that “concerns about civility and mutual respect can never be used as a justification for closing off discussion of ideas, however offensive or disagreeable those ideas may be to some members of our community.”

The University of Chicago was one of the first higher education institutions to directly address free speech on campus, publishing the “Chicago Statement” in January of 2015. The statement maintains that “it is not the proper role of the University to attempt to shield individuals from ideas and opinions they find unwelcome, disagreeable, or even deeply offensive,” and that “concerns about civility and mutual respect can never be used as a justification for closing off discussion of ideas, however offensive or disagreeable those ideas may be to some members of our community.”

See which other universities have adopted the Chicago Statement, and which colleges rank highest on RealCelarEducation’s 2021 College Free Speech Rankings.

Lee Rowland, attorney with the ACLU’s Speech, Privacy, and Technology Project discusses Campus Free Speech Realities and Myths (16 min):

Social Media & Big Tech

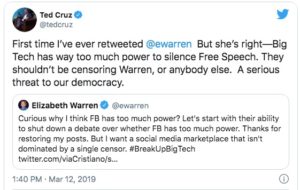

On social media, debates on free speech have “been simmering for years.” When major online platforms were getting their start, most “preferred to moderate as little content as possible,” but today “companies such as Facebook employ thousands of moderators and use artificial intelligence and other technology to keep tabs on what their users post.” This means that these platforms “have enormous power and influence over public discourse in our nation,” begging the question: “Should they have unlimited authority to decide for themselves who can and cannot share their views with other Americans on these extraordinarily powerful means of communication?” And, in the case of social media bans on former president Trump, what does it mean when a corporation can censor a government official?

The companies “have become indispensable for the speech of billions,” and as such have extensive power in their “ability to deny access to the platforms that shape our public discourse,” says ACLU lawyer Kate Ruane. As private companies, they are under no obligation to give any user a platform; according to Jillian C. York, director for international freedom of expression at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, companies’ First Amendment rights allow them “to curate their platforms as they see fit.” At the same time, this also gives them “enormous influence over who can speak, what can be said, and who gets heard.”

The companies “have become indispensable for the speech of billions,” and as such have extensive power in their “ability to deny access to the platforms that shape our public discourse,” says ACLU lawyer Kate Ruane. As private companies, they are under no obligation to give any user a platform; according to Jillian C. York, director for international freedom of expression at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, companies’ First Amendment rights allow them “to curate their platforms as they see fit.” At the same time, this also gives them “enormous influence over who can speak, what can be said, and who gets heard.”

This is not the first time the theme has emerged with changing technologies. In the 1920s, many had similar fears that a few wealthy individuals would buy all the radio frequencies in an area and essentially take over the airwaves. With the Communications Act of 1934, Congress established the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) “to ensure that broadcast stations operate in the public interest.” In 1949, the FCC imposed the Fairness Doctrine, which required radio and tv broadcasters “to cover controversial issues of public importance in a fair and balanced manner.” Although the Fairness Doctrine was repealed by the Reagan administration in 1987, University of Chicago Law School’s Geoffrey Stone notes that today’s social media platform debates bring up again the question of whether or not these platforms should “be required to operate in a fair and balanced manner.”

Anti-monopoly Argument

Many concerned citizens “fear that these online platforms hold outsized power over public discourse because so much speech flows through them.” Gallup found that between August 2019 and February 2021, negative views of Big Tech companies among Americans increased from 33% to 45%, and the percentage of Americans who want government to regulate these technology firms increased from 48% to 57%. Policymakers have called to break up big tech for these reasons, as stated by Senators Elizabeth Warren and Ted Cruz:

Others are less inclined to use anti-monopoly tools to solve free speech problems, “arguing that such regulatory intervention opens the door for government overreach and abuse of power.” Neil Chilson and Casey Mattox from the Charles Koch Institute also argue that while antimonopoly efforts to promote competition can help free speech, in this case, “increasing the number of competitors will not help because current free speech concerns are not caused by a lack of competition.” In fact, they maintain that increasing the number of competing speech platforms could at best “force us into siloes of common opinion, diminishing viewpoint diversity on any one platform,” or at worst “further push the most hateful and vile to specialized platforms that would reinforce their tendencies rather than temper them.” Part of the problem is that there is a lack of consensus about what should be taken down on these platforms, not a lack of competition. For more on monopoly power and antitrust laws, see The Policy Circle’s Deep Dive on Antitrust Laws in Our Lives.

Instead of pursuing antimonopoly tools, there are other means of holding big tech companies accountable. One major issue is the “‘ad model’” – many large tech companies have made their fortunes by “selling advertisements to companies wishing to take advantage of the intricate profiles of potential consumers developed by the tech giants.” This targeted advertising, however, can contribute to “controversial and inflammatory content” as well as “polarization, and the spread of misinformation and disinformation.” In fact, as ad revenue is pulled away from traditional media companies and redirected online, it means that tech giants also have power “over media outlets’ ability to reach existing and new audiences,” which greatly alters “the economics and editorial approach of the news business.” One suggestion is building social media algorithms with goals other than maximizing ad revenue. How to go about this and change a well-ingrained system is unclear, but given that many people are becoming more aware of how their data is used to target advertising, new possibilities may develop. For more on what data is used for online, see The Policy Circle’s deep dive on Data Privacy and Cybersecurity.

Other options include strengthening user privacy protections, and even “self-regulation efforts or the development of internal ethical codes by the tech companies.” Such efforts would need to be enforced; for example, a number of major platforms endorsed the Santa Clara Principles on Transparency and Accountability in Content Moderation in 2019, but only Reddit adheres to the principles. In May 2020, Facebook created its own Oversight Board, an international group of academics, lawyers, and human rights advocates that “has been likened to a Supreme Court for content decisions” and is meant to help make the final call on difficult content decisions. Facebook created and funds the board, but no one at the company can overrule its decisions, Mark Zuckerberg included. A five-member panel of the 20-person oversight board reviewed and upheld the decision to suspend President Trump’s accounts in June 2021. However, Facebook has indicated trouble keeping up with all recommendations coming from the oversight board.

Overall, a more substantial understanding of how these companies operate is necessary. Due to “a lack of transparency on the part of the platforms about their human and machine-made decisions,” the general public does not completely understand how these decisions affect public discourse. Jillian C. York of the Electronic Frontier Foundation says that platforms “know what they need to do, because civil society has told them for years. They must be more transparent and ensure that users have the right to remedy when wrong decisions are made.”

For more on “the dark side of social media,” see the Netflix documentary, The Social Dilemma.

Section 230

Section 230 is a component of the Communications Decency Act that protects internet service providers and online platforms “from liability for the decisions they make about the content they host,” meaning they cannot be held liable (in most cases) for what third parties post. Joe Toscano, former Google consultant, explains that Section 230 was originally meant to enable innovation. Today, given the size and influence of social media platforms, many believe the protections offered by Section 230 are no longer necessary and have called to repeal or amend it. According to Toscano, social media platforms’ increased content moderation efforts “‘proves that they now realize they are responsible for the content and now it’s time to talk about Section 230.’”

Others are more hesitant to make changes to Section 230. Jillian C. York predicts that repealing Section 230 “would hinder competitors to Facebook and the other tech giants, and place a greater risk of liability on platforms for what they choose to host.” While larger platforms could probably afford to comply with any regulations, smaller competitors with fewer resources likely could not. New rules would not only affect big tech companies, but also small startups such as photosharing services, websites with comment sections, or review websites. If the intention is to limit the monopoly-like influence of social media platforms, this would essentially have the opposite effect. Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR), original co-author of Section 230, notes that the First Amendment, not 230, protects free speech, and says, “‘Pretending that repealing one law will solve our country’s problems is a fantasy.”

The Wall Street Journal dives deeper into the rules of what can be said on social media (8 min):

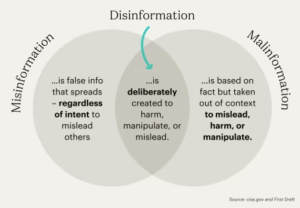

Misinformation

A related dilemma is that of misinformation spreading on social media. Unless fraudulent news crosses “specific legal red lines,” such stories “are not illegal, and our government does not have the power to prohibit or censor them,” explains Suzanne Nossel, former deputy assistant secretary of state for international organizations at the State Department. Government can play a role as can news outlets, social media platforms, and fact-checking groups, but each actor must also respect the extent to which they can pursue interventions. Going too far with restrictions can be just as damaging to free speech as fake news stories, and will likely do little to help “the related erosion of public trust,” Nossel warns.

In fact, globally, trust in information sources from traditional media to social media is at record lows, according to the January 2022 Edelman Report. The Edelman Report also found that, because of this erosion of trust, respondents said that increasing their media and information literacy is one of the most important things they can do for themselves. Nossel advocates this as well, saying that the “best prescription against the epidemic of fake news is to inoculate consumers by building up their ability to defend themselves.”

How has Americans’ trust in social media changed over time? See The Policy Circle’s Rebuilding Trust in America Brief to find out.

To learn more about big tech’s role in free speech realm, watch The Policy Circle’s Move The Needle Virtual Experience Free Speech Series: Big Tech Tightrope: Balancing Free Speech, Privacy & Innovation.

Conclusion

On an individual and community level, the right “to express one’s thoughts and communicate freely with others affirms the dignity and worth of each and every member of society.” On a societal level, freedom of expression is “necessary to our system of self-government and gives the American people a ‘checking function’ against government excess and corruption.” As 21st century debates over First Amendment rights continue in our society from college campuses to social media platforms, we must remember these rights are “vital to the attainment and advancement of knowledge, and the search for the truth.”

Thought Leaders & Additional Resources

Louisiana State University’s Fight Fake News

Philanthropy Roundtable: Free Speech Update

Philanthropy Roundtable: Resisting Hate with Free Speech, Not Censorship with Nadine Strossen

Noam Chomsky discusses Free Speech on campus at the University of Arizona in 2018.

Foundation for Individual Rights in Education

OpenMinds is an online program based in evidence-based psychology that takes users on a five-step journey to prepare them emotionally, psychologically, and practically for constructive engagement across differences. It is available for use in academic, corporate, non-profit/religious settings as well as for individual use.

Bridge the Divide seeks to promote political conversation amongst youth in a time of great division in both American and global political affairs. The international group was started and is run by young people – some of whom are still in college – to engage politically active students in stimulating, productive and respectful conversation to bring about positive change in the world.

Heterodox Academy aims to “create college classrooms and campuses that welcome diverse people with diverse viewpoints and equip learners with the habits of heart and mind to engage that diversity in open inquiry and constructive disagreement.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Find out what your community is doing about free speech.

- Do you know the state of free speech in your community or state?

- What are your alma mater’s policies?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Who are the board members determining policy at your alma mater or local educational institutions?

- What steps have your state’s or community’s elected and appointed officials taken?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with local businesses, community organizations, and school boards.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, [email protected], for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policy makers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Re-read the Bill of Rights and the Constitution.

- Examine OpenMind and whether or not it could be a good fit for use in your church, school, workplace, or at home.

- Engage with college students you know.

- Keep up with policies at your alma mater, and determine whether or not you support its free speech policies.

- Consider sending a letter to the administration if, for example, you are uncomfortable making financial contributions given certain policies.

- With a group of friends, your kids, or with your Policy Circle, try this “Debate it!” activity from the National Constitution Center, which asks you to consider a variety of scenarios in which free speech might be limited.

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.