Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this Brief

View the Executive Summary for this Brief

How have two decades of war shaped and influenced the perceptions of Americans on their military? According to a March 2022 opinion poll by Gallup, 68% of Americans believe the United States military should rank first in the world. However, according to the same poll, 51% of respondents felt the United States actually did rank first. In addition, the poll found that 36% of Americans believed the United States was spending the right amount of money on national defense, down from 42% a year earlier, before the withdrawal from Afghanistan.

This video from Kite & Key Media explores perceptions about defense spending.

The brief will answer the following questions: How much of our federal tax dollars are spent on defense, and what does this funding cover? How are the armed forces structured? How do active-duty service members touch their communities during and after their service? What are the issues and challenges facing military personnel and their families, veterans, and the agencies charged with funding and operating these vital institutions?

Why It Matters

The federal government has a constitutional responsibility to protect its citizens. Under Article 4, section 4, the Constitution states: “the United States shall guarantee to every state in this union a republican form of government, and shall protect each of them against invasion.”

The Department of Defense (DoD) oversees the U.S. Armed Forces and is the largest government agency in the United States. According to its mission statement, it provides the military forces needed to deter war and ensure the nation’s security. Beyond that, its missions vary, including natural disaster response, humanitarian aid, and rescue operations.

The military also has a large impact on the U.S. economy. It serves as a career path, accounting for nearly 1.4 million jobs as of April 2022, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. In addition, in some states, having a military base in a community has an economic impact on the local economy by creating direct and indirect employment opportunities. In addition, investments in military technologies frequently produce technologies that improve civilian life, with examples ranging from the voice-internet search tool SIRI to GPS navigation.

An estimated 18 million Americans, (about 7% of the population) are veterans of the U.S military. The Department of Veterans Affairs was created to fulfill President Abraham Lincoln’s promise: “To care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan.” For more information on the issues facing veterans today, see The Policy Circle’s Brief on Veterans.

Structure

The U.S. military is a civilian-controlled agency of the federal government. Ultimate authority lies in the executive branch with the president as commander in chief, rather than a military official.

The Department of Defense (DoD) is the primary agency in the Pentagon, which is the nerve center of the country’s armed forces – the largest of the U.S. government institutions.

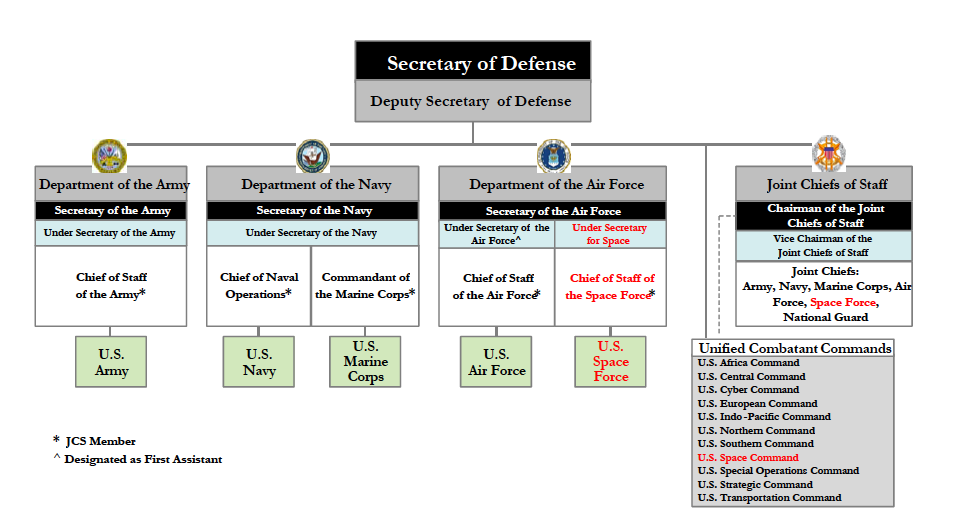

The secretary of defense is the principal defense policy advisor to the president and is second in command of military forces after the president. He or she is also responsible for formulating defense policy and other policy matters of concern to the DoD. The secretary of defense manages the DoD through a combination of advice and support from staff, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and direction from both the president and Congress.

The Joint Chiefs of Staff are responsible for ensuring the readiness of the armed forces. They serve as the president’s military advisors, but are not part of the military chain of command, meaning they have no executive authority to command combat forces.

The National Security Act of 1947 initially authorized three military departments: the army, the navy and the air force. Each military department is led by a civilian secretary who is appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Today, the DoD includes the following branches:

The National Security Act of 1947 initially authorized three military departments: the army, the navy and the air force. Each military department is led by a civilian secretary who is appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Today, the DoD includes the following branches:

- Army: the principal land force (includes special forces known as Green Berets);

- Navy: the principal maritime force (includes special-operations team Navy SEALS);

- Marine Corps: provide support for other branches through land, combat, sea-based, and air-ground operations;

- Air Force: the principal aerospace force;

- Space Force: responsible for global space operations;

- National Guard: the principal force for states, territories, and the District of Columbia, with each state and territory having its own National Guard.

The chart below illustrates how the branches are organized under the three departments:

*Space Force, highlighted in red, was created in 2019

*The National Guard is divided between the Army National Guard and the Air Force National Guard

Additionally, the Coast Guard is usually considered a branch of the armed forces, as well as a law enforcement agency, regulatory agency, member of the intelligence community, and first responder. The Coast Guard normally operates under the Department of Homeland Security, but transfers to the Department of the Navy during wartime. The Coast Guard maintains border security at U.S. ports and waterways and protects the United States from maritime threats along more than 95,000 miles of U.S. coastline.

Each military branch has two components:

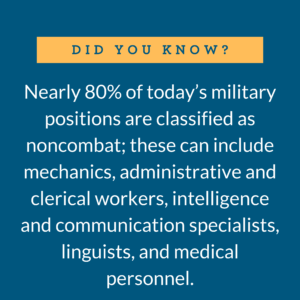

- Active refers to full-time service members, the individuals who are stationed all over the world in combat and non-combat situations. These servicemembers and their families live on or near bases, expecting to move every 3-5 years as determined by the needs of the armed forces.

- Reserve refers to the federal reserve force that augments the active component as needed. Individuals are part of the military in part-time capacity unless mobilized full time to meet federal needs, as determined by the president.

There are eleven Unified Combatant Commands with specific geographic or functional missions that span multiple branches. For example, the U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) is responsible for planning and conducting worldwide counterterrorism operations usually classified as “time sensitive, clandestine, low visibility, conducted with and/or through indigenous forces, requiring regional expertise, and/or a high degree of risk.” USSOCOM includes the U.S. Army Special Operations Command; the Naval Special Warfare Command; the Air Force Special Operations Command; and the Marine Corps Forces Special Operations Command.

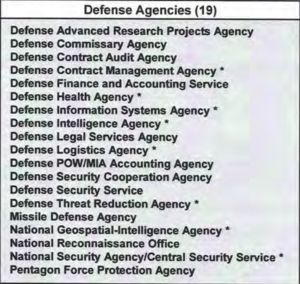

The DoD also includes a number of agencies that coordinate functions related to national security, such as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), which oversees 250 research and development programs for DoD’s academic, corporate, and governmental partners. Agencies such as the Defense Intelligence Agency and the National Security Agency are specifically designated as Combat Support Agencies (indicated with * in the chart below).

By The Numbers

Budget

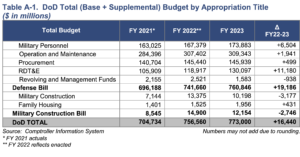

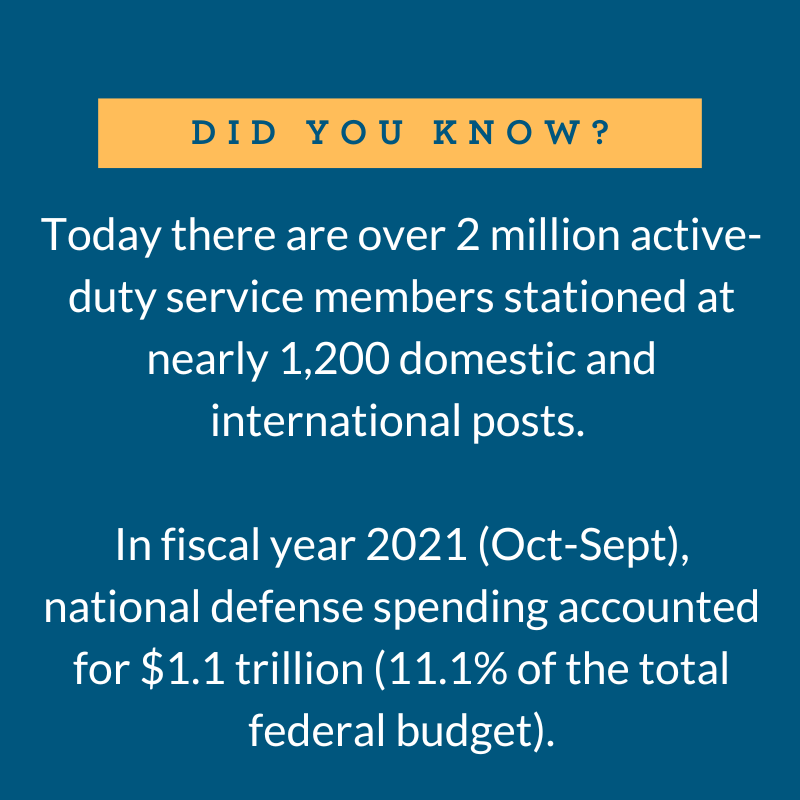

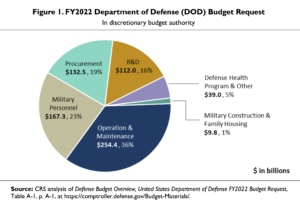

According to the Congressional Budget Office, about one-sixth of total federal spending (mandatory and discretionary) goes to national defense. In fiscal year 2021 (Oct-Sept), spending for national defense amounted to $1.1 trillion. This accounted for 11.1% of the total U.S. budget, the fourth-largest amount behind Income Security (19.9%) Medicare (13.7%) and Social Security (11.8%).

The majority of this national defense spending is in the form of the Defense Appropriations Act, which provides funding for most activities of the DoD, including the military departments as well as the Office of the Secretary of Defense and some DoD agencies. Within the DoD, this covers the following expenses:

- Personnel, including pay and retirement benefits;

- Operations and maintenance, including training, planning, maintaining equipment;

- Health care for the military healthcare system, which is separate from the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA);

- Procurement of weapons and systems;

- Research and development;

- Defense-related activities carried out by other agencies such as the Department of Energy and the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

A separate appropriations bill, outside of the Defense Appropriations Act, funds military construction.

In order to improve transparency and accountability, Congress approves the intelligence budget separately from the national defense budget. The intelligence budget includes allocations for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, and certain activities under the DOD such as the National Security Agency (NSA); these allocations totaled $84.1 billion in FY2021.

Personnel

An individual must be at least 17 years old to enlist in the active-duty military, with additional age limits to join for each branch.

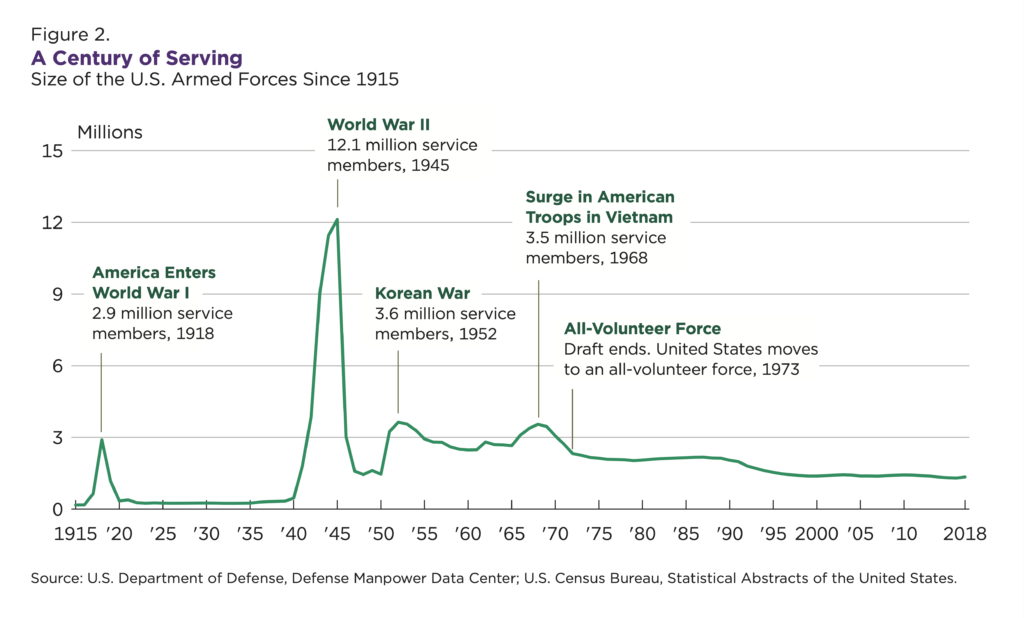

The Selective Service registers individuals and runs the draft. Almost all men (citizens and immigrants) ages 18-25 must register; the registration does not include women. The U.S. military has been an all-volunteer force since 1973, but if Congress and the president authorize a draft, the system would start calling registered men for duty.

Personnel totals for the U.S. military include the following:

- 1.3 million active-duty service members

- 467,000 Army

- 343,000 Navy

- 175,000 Marine Corps

- 333,000 Air Force/Space Force

- Approximately 50,000 Coast Guard personnel

- According to demographics data from the DoD from 2020, women account for 17.2% of the active-duty force but Black or African-American women account for 26.1% of that amount. For men and women, Black or African-Americans account for 17.2% of active-duty service members even though they make up 12.4% of the U.S. population, according to 2020 census data.

- In addition to active-duty service members, just over 1 million total reserve forces can be activated immediately at the president’s direction. Members of the Army Reserve generally spend one weekend a month and two weeks a year in training. The Department of Veterans Affairs provides information on how employers can support reserve soldiers. Individuals can also enlist to become reserve soldiers. Their numbers include the following:

- Approximately 600,000 civilian personnel:

-

-

- 196,000 Army Civilian

- 200,000 Navy Civilian

- 22,000 Marine Civilian

- 180,000 Air Force Civilian

-

The armed forces follow a hierarchical leadership structure with clearly defined levels of authority. Among individuals, there are different levels for officers (called grades) that are defined in law. Rank refers to the order of precedence among those in different grades or within the same grade. Officers comprise about 18% of the armed forces and outrank all enlisted personnel. See titles and corresponding pay charts.

Personnel are stationed at bases around the world. The United States maintains around 750 military bases abroad in 80 foreign countries and territories. Domestically, there are more than 420 military installations across the 50 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, and Puerto Rico. Find military installations here, and reserve bases here.

Veterans

An estimated 18 million Americans (about 7% of the population) are veterans of the U.S military. Between 2000 and 2018, the veteran population declined by about a third, from 26.4 million to 18 million. The armed forces today are significantly smaller today than they were in the past, partially due to today’s all-volunteer system, as well as more aging veterans. The median age of U.S. veterans is 65.

Role of Government

Federal

The U.S. Constitution gives authority over the armed forces to the president and Congress.

Executive Branch

The President

Article II, Section 2, Clause 1 of the U.S. Constitution states, “The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States…” The purpose of this clause is to vest military power in the hands of a civilian leader, rather than a military leader.

As commander in chief, the president exercises authority over the military in the following ways:

- Selecting appointees and senior officers, and approving military promotions;

- Managing the federal budget process; and

- Formulating national security policy.

The National Security Council (NSC) is the “President’s principal forum for national security and foreign policy decision making,” and includes the Secretary of Defense. The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Director of National Intelligence advise the NSC.

Congress

Article I, Section 8, Clause 12 of the U.S. Constitution states, “The Congress shall have power … to raise and support Armies … make rules for the government and regulation of the land and naval forces … for calling forth the militia to execute the laws of the Unions, suppress insurrections and repel invasions.”

Congress exercises its authority over the military by:

- Authorizing and appropriating funds for the military;

- Providing advice and consent on the principal appointees nominated by the president; and

- Declaring war.

Each year, Congress considers appropriations measures for national defense and homeland security through legislation including the National Defense Authorization Act. The annual “Department of Defense Appropriations Act primarily provides funding for most activities of the Department of Defense (DoD), including the Departments of the Army, Navy (including Marine Corps), and Air Force (including Space Force); Office of the Secretary of Defense; and Defense Agencies.”

The House and Senate Committees on Appropriations exercise jurisdiction over annual appropriations measures. Specifically, in regards to national defense, the following subcommittees are involved:

- The House and Senate Subcommittees on Defense;

- The House and Senate Subcommittees on Military Construction, Veterans Affairs, and Related Agencies;

- The House and Senate Subcommittees on Energy and Water Development.

Find out if any of your congressional representatives sit on any of the subcommittees that oversee the armed forces here.

Congress & The President

The Commander in Chief Clause is not without controversy, as it is not clear “how much authority the Clause gives the president beyond operations approved by Congress.” Presidents have claimed authority over a wide range of military actions, such as making military deployments without congressional authorization. For example, President Harry Truman sent troops to Korea without a congressional declaration of war; President Dwight Eisenhower relied on covert CIA operations; President John F. Kennedy was the primary decision maker regarding Cuba; and President Richard Nixon’s decision to bomb Cambodia during the conflict in Vietnam prompted Arthur Schlesinger’s description of “the imperial presidency.”

To scale back presidential power, Congress attempted to define when and how a president could send troops to battle with the 1973 War Powers Resolution. The Resolution “provides that the president must consult with Congress when introducing U.S. forces into ‘hostilities.’”However, many argue the main issue with the War Power Resolution was that Congress did not define the scope of “‘hostilities,’” which has allowed presidents to interpret it to mean anything short of all-out ground invasion. For more on the balance between Congress and the president when it comes to controlling the Armed Forces, see The Policy Circle’s Executive Branch Brief.

State

The military operates under the executive branch as a federal government agency under the DoD, but the National Guard is primarily state based. When activated for a federal mission, it is the reserve component of the Army; when not activated, it is a state-based force under the control of the state’s governor. There are 54 separate National Guard organizations: one for each of the 50 states and one each for Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the District of Columbia. While the National Guard for Washington, D.C. is exclusively a federal organization that operates under federal control, the other 53 are state or territorial organizations.

Across the 50 states, Guam, Puerto Rico, and Washington, D.C., there are more than 420 military installations. These bases sustain the presence of U.S. forces at home, and are used to train and deploy troops, maintain weapons systems, care for wounded, and support military service members and their families through housing, health care, childcare, and education.

See state resources for military members and families here.

Local

Active-duty service members and their families live on or near military bases. Military bases have their own grocery stores, shopping centers, food courts and restaurants, dry cleaners, barber shops and hair salons, daycare centers, schools, and other daily amenities that make them an integral part of the local military community.

Sometimes, this results in military bases being “relatively isolated economic entities, purchasing base needs outside the community and spending income at the base rather than in the local community.” Even so, bases can “provide an economic anchor to local communities,” particularly in rural areas.

Across the country, military bases employ hundreds of thousands of military personnel, in addition to contractors and civilian employees. Most of these employees are community members. Stephen Fuller, economist at George Mason University, found that “‘Military workers’ spending off base far outweighs tax-free incentives on base.’”

Some studies looking at the effect military bases have on the local community have found:

- Positive effects of services members volunteering for outreach to local community;

- A federal presence, such as through a military base, has been linked to tempered economic downturns in the local economy;

- The military can be a primary source of business through contracts with local businesses.

The DoD’s Office of Local Defense Community Cooperation (OLDCC) “leverages capabilities of state and local partners through grants and technical assistance” to help towns, cities, and states build sustainable and mutually beneficial partnerships with the DoD. OLDCC’s $1.3 billion portfolio of grants ensures:

- Supply chains are responsive;

- Communities can support local military installations through economic development;

- Civilian activities can support and engage with the DoD;

- Defense communities around the country are supported, and the quality of life for troops and their families is provided for.

Find military installations, schools, reserve units, and local centers for enlisting.

Private Sector

The DoD works closely with the private sector primarily through government contracts. In some cases, military contracts with local businesses are a significant source of revenue generation in communities, spearheaded by the DoD’s Office of Small Business Programs.

For larger contracts with national and international vendors, the Defense Contract Management Agency provides contract administration services for the DoD and other federal agencies. It manages 250,000 contracts valued at more than $3.5 trillion with 13,000 contractors worldwide. See a full list of DoD contracts (valued at $7.5 million or more) here.

Health care is another area in which the private sector is involved. For the most part, health care for active-duty service members and veterans is provided by the DoD and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), respectively, but some individuals may turn to private health care providers. In the Bush Center’s 2021 survey on Advancing Veteran Employment, Education & Health and Well-being, fewer than half of respondents agreed that doctors and providers in private practice understand the military culture or health challenges facing post-9/11 veterans and service members. This has led to a rise in specialized care options designed for veterans, including the Warrior Care Network, the Veteran Wellness Alliance, the Cohen Veterans Network, and the SHARE Military Initiative at Shepherd Center.

Finally, there are many organizations that serve service members, their families, and veterans. The United Service Organization (USO) is one of the nation’s leading organizations serving service members and their families. AmericaServes is a national coordinated network of organizations dedicated to serving the military community. Academic institutions are another resource for veterans, and often partner with these organizations; one example is Syracuse University’s Institute for Veterans and Military Families. See this directory of veterans service organizations.

Challenges & Areas For Reform

Top Management & Operation Challenges

Every year, executive branch agencies’ Inspectors General identify the top management and challenges facing their particular agency. The Department of Defense’s annual report provides Congress and the agency’s military and civilian leadership with a detailed overview of its most serious challenges. For 2022, these challenges include the following:

- Maintaining and building alliances to counter global terrorism and address aggression from strategic competitors, namely Russia and China;

- Updating outdated systems that are not keeping up with adversaries’ capabilities, principally nuclear and missile defenses and cyberspace operations.

- Reinforcing the supply chain and reducing the reliance on strategic competitors, illustrated during the COVID-19 pandemic;

- Improving financial management and budgeting, such as ensuring the DoD is paying fair and reasonable prices;

- Building resilience to environmental stressors to mitigate risks and costs to operations, equipment, and personnel;

- Recruiting and retaining a modern workforce, which presents challenges as the DoD must compete with the private sector for new talent in science and technology fields;

- Protecting the health and wellness of service members and families.

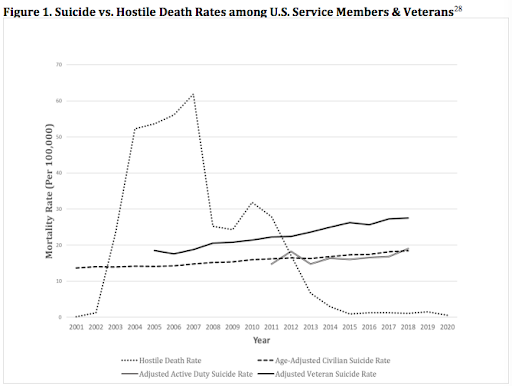

Mental Health

Depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), suicide, traumatic brain injury, substance abuse, and interpersonal violence are some of the most harmful and prevalent issues facing military service members and veterans. According to Brown University’s Cost of War, since 2012, suicide rates for active-duty service members and veterans (30,000+) have outpaced those of combat-related deaths in post-9/11 conflicts (just over 7,000).

Experts cite a few reasons to explain the rise in mental health concerns:

- The nature of warfare, from exposure to combat to the protracted length of war;

- Military culture, from rigorous training and schedules to the dominant masculine identity that makes asking for help during trauma difficult and maintains the idea that acknowledging mental illness may be viewed as a sign of weakness.

An additional challenge facing service members and increased stigma surrounding mental health is confidentiality. Military patients know that much of their medical life is not private and in some cases, medical professionals have command notification requirements. This means a service member’s file may be flagged if he or she – or even a family member – seeks care for mental health.

Congress provides $20 million annually to the DoD for suicide prevention programs and research, and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) receives billions of dollars to combat suicide annually. The DoD also began Resilience Training in 2008, which has reported reductions in self blame and increased positive coping skills among service members. Additionally, the Army shortened deployment length and increased dwell time (time between deployments) at members’ home bases in 2011, based on evidence that longer dwell time is associated with a lower risk of PTSD.

One dilemma with shorter deployments and increased dwell times has been the shrinking numbers of active-duty military, compared to other periods in history. The U.S. military has been voluntary since 1973, which comparatively has resulted in fewer total service members. Army Chief of Staff General James McConville says that while he prefers rotations every four years for service members, in actuality rotations are closer to 1-3 years. In sum, shrinking forces will only add extra strain to existing troops, creating a recipe for burnout.

Benefits offered to the military can encourage young people to enlist. According to the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service, “high school students increasingly view military service as incompatible with postsecondary education and often choose to attend college or vocational school in lieu of joining the military, even when they are interested in serving.” Benefits, as well as increased opportunities for youths to explore military service opportunities – such as Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC), which allows individuals to simultaneously attend college and train to be an Army officer – can strengthen recruiting.

Refer to The Policy Circle’s Brief on Mental Health for broader discussion on the issue.

Spending

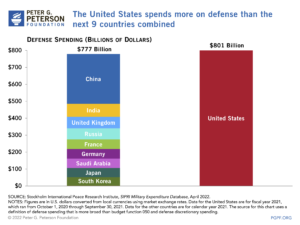

On the global stage, world military expenditures passed $2 trillion for the first time in 2022, hitting $2.1 trillion and marking the seventh consecutive year of increased spending. The United States, China, India, the UK, and Russia accounted for 62% of those expenditures. In total, the United States spends more on defense than all of these countries combined (note that defense spending as portrayed in the chart is defined more broadly than defense discretionary spending).

Domestically, the annual Defense Appropriations Act funds most of the DoD’s activities, including the three main military departments (Army, Navy, Air Force), the Office of the Secretary of Defense, and agencies under the DoD. Military construction and family housing programs, the Army Corps of Engineers programs, and the TRICARE program of medical insurance for military retirees are not included, nor is the budget for the VA.

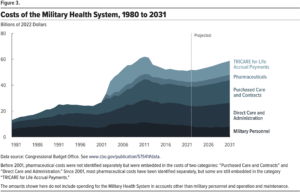

The Congressional Budget Office forecasts the continued growth in costs related to national defense, primarily:

- The continued growth in costs of compensation for service members and civilian employees;

- Growth in costs to operate and maintain bases and equipment;

- Increased spending on new, advanced military equipment and weapons due to shifts in focus to conflicts with technologically advanced militaries;

- Continued growth in costs to military health care plans (see below)

Whether the United States spends too much or too little on its defense budget is heavily debated. In fact, according to Gallup polls from February 2022, 32% of respondents felt the government spends too little on the military, 34% believe the government spends the correct amount, and 31% believe the government spends too much.

Those who believe the United States spends too much on the military generally point to the following issues:

- Military spending dwarfs diplomatic and foreign assistance spending; and

- Runaway costs. For example, a project to modernize the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter Jet with new computing systems and software initially began in 2018 with an end date of 2026 and an estimated cost of $14.4 billion. However, a Government Accountability Office report from 2021 found the schedule was pushed back three years to 2029 and that $741 million had been added to the budget.

In contrast, those who believe the United States does not spend enough on the military make the following points:

- Military spending has only amounted to 3-5% of GDP since the 1990s, compared to 8-9% during the 1960s;

- The president’s budget request for fiscal year 2023 (Sept-Oct) asked for $773 billion for the DoD, which Congress is concerned will not be enough;

- Congress must consider the priorities submitted by military departments and combatant commands;

- The pace of pay increases has not kept up with the pace of inflation. For example, Congress had approved a 4.6% pay raise for service members, but according to June 2022 data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, inflation is running at 8.6%.

- Finally, additional spending to address challenges from the war in Ukraine to supply-chain problems are also on the table. As of mid-June 2022, seven House Armed Services subcommittees had released initial information on priorities for the National Defense Authorization Act, and the House Appropriations Defense Subcommittee and Senate Armed Services Committee were also drafting funding bills.

Spending In Communities

In some cases, military installations may have substantial impacts at the state and local levels in terms of salaries, benefits to military and civilian personnel and retirees, defense contracts with state businesses, and tax revenues and other military spending. However, the information is tempered by federal budget cuts, closures of bases and the impacts of the troop withdrawals from Afghanistan and Iraq. In state case studies, some states did not find any economic gain from having a military base while others found a strong impact. States that did report having an economic gain include the following:

- In North Carolina, military bases supply 578,000 jobs and generate $66 billion in gross state product, 10% of the state’s overall economy.

- In Colorado, revenue and spending from military installations generates a total economic impact of $27 billion across the state.

- In Kentucky, military employment exceeds the next largest state employer by more than 20,000 jobs.

- In Texas, military installations contributed over $120 billion to Texas’ economy in 2019, and more than 630,000 jobs statewide.

- In Maryland, Fort Meade is the largest employer in the entire state, providing over 50,000 direct jobs and thousands more indirect jobs.

- In Hawaii, direct military spending of $6.5 billion contributed to $12.2 billion in output and over 100,000 full-time equivalent jobs statewide.

Besides military bases, reserve units are also important in the communities and sometimes overlooked. See state-by-state economic impacts of reserve units here.

A number of studies have looked closely at what happens to a community when a military base closes; such closures came about as a result of the Budget Control Act of 2011 sequestration that led to a reduction of soldiers and civilian employees at bases across the country. These studies found:

- An immediate impact from the loss of military and civilian jobs;

- A decline in local tax revenue, leading to fewer public services;

- Declines in enrollment among schools with high proportions of military family children.

When a base closes, it can hold certain advantages for redevelopment, such as serving as a new industrial site for a manufacturing facility, airport, or research lab, but government programs to assist communities affected by these base closures appear to be critical. “Over the five-to six-year phasing out of a base…environmental cleanup, successful property transfers to a local redevelopment authority, and widespread community commitment to a sound base reuse plan have been shown to be crucial elements in positioning communities for life without a military installation.”

Conclusion

The August 2021 withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan capped 20 years of armed conflict that affected a generation of people in both countries. The war also changed perceptions of the military and attitudes about how involved the United States should be in the foreign affairs of other countries. As other regions in the world become embroiled in conflict, from the Syrian civil war, which has been ongoing since March 2011, to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, the United States must weigh how it will become involved: either through its armed forces, diplomacy, sanctions, or a combination. As the overseer of the U.S. armed forces, understanding how the Department of Defense (DoD) works as well as its budget and impact can help shape how the country responds to other conflicts across the globe.

Ways To Get Involved & What You Can Do

Measure: Find out about the presence of the armed forces in your state and district.

- Is there a military base, reserve unit, or military school in your community, or nearby in your state?

- If so, do you know the economic impact of the base in your community?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Are any of your state’s congressional representatives on a committee with jurisdiction over the military?

- What steps have your state’s or community’s elected and appointed officials taken?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with law enforcement, first responders, faith-based organizations, local hospitals, community organizations, school boards, and local businesses.

- For example, this high school created a scholarship to provide assistance to students with a parent or guardian serving in the military.

Plan: Set some milestones with others to maximize your impact based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, [email protected], for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policy makers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Consider volunteering with an organization that benefits service members, their families, or veterans in your community.

- Is there a USO Center near you?

- Talk to local business owners or reach out to your local chamber of commerce to find out about contracts with the military, or the economic presence of a military installation nearby.

- Consider joining with other community members to form community liaisons to reach out to bases and hold events such as open houses, classes, and job fairs.

- Acknowledge military families in the schools and businesses that you are part of.

- Reach out to military families and ask about their experiences.

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.