While negotiations and tariffs directed at China have taken center stage, the U.S. has also levied tariffs against the EU and has renegotiated trade deals with Canada and Mexico. Why? How exactly do tariffs work? And what does all this mean for free trade?

Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

Back to Basics: What is a Tariff?

The Tax Policy Center defines a tariff as “a tax on imported goods.”

If it’s a tax, someone has to pay, right?

Right. An interesting debate is, Who bears the brunt of a tariff? Such taxes are almost always paid by the importer, not the exporter. The importer, usually a domestic firm or business, will then often “pass its higher after-tax costs on to consumers” by raising the price of the goods enough to cover the extra costs incurred by the tariff. For example, due to tariffs on steel and aluminum, experts calculated the cost of washing machines rose by about $82 per unit in 2018.

Right. An interesting debate is, Who bears the brunt of a tariff? Such taxes are almost always paid by the importer, not the exporter. The importer, usually a domestic firm or business, will then often “pass its higher after-tax costs on to consumers” by raising the price of the goods enough to cover the extra costs incurred by the tariff. For example, due to tariffs on steel and aluminum, experts calculated the cost of washing machines rose by about $82 per unit in 2018.

Do Tariffs work?

Generally, the purpose of placing high tariffs on another country’s products is to raise the price on their products to make them cost more than similar products produced in one’s own country. The goal is for people to buy their country’s less expensive products, which keeps more money in their own country and grows their own economy. This should also protect domestic businesses and jobs producing these products, rather than sending money to other countries. Harvard Business Review goes in depth in this analysis of Economic Theory about Tariffs.

Why the Focus on China?

Trade Practices

Trade Practices

The Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) investigated China’s trade practices and detailed how they operate. Two of the greatest challenges are foreign ownership restrictions and cyber intrusions.

First, foreign ownership restrictions “prohibit foreign investors from operating in certain industries unless they partner with a Chinese company.” With these restrictions come burdensome processes that “force technology transfer in exchange for the numerous administrative approvals needed to establish and operate a business in China.” Essentially, this means many foreign companies must share their intellectual property simply to operate in China. Chinese companies do not face the same restrictive policies in the U.S. By “extracting intellectual property – sometimes coercively” and providing “market-disorienting subsidies to domestic industries,” China’s government is undercutting the competitive edge of U.S. companies.

Second, “the Chinese government has conducted and supported cyber intrusions into U.S. commercial networks,” meaning China’s government has gained access to confidential business information, from technical data to sensitive negotiation details.

You can read the full report from the USTR here. James Lewis of the Center for Strategic and International Studies also further breaks down these issues and what they mean for trade.

Trade Deficit

Trade Deficit

A trade deficit is the difference between how much your country buys/imports from another country and how much your country sells/exports to that country. The jury of economic experts is still out on how much trade deficits matter, but “China’s widening surplus,” unfair trade practices, and overall imbalanced trade between the U.S. and China were concerns for the Trump Administration.

Areas for Reform

China

During trade talks in May 2019, China backtracked on commitments it had made for freer trade, which prompted then-President Trump to increase tariffs from 10% to 25% on $200 billion worth of Chinese products. China countered in June 2019 by raising tariffs between 5% and 10% to between 10% and 25%, affecting $60 billion worth of mostly U.S. agricultural goods such as soybeans, beef, and pork.

Big brand names including Costco and Walmart raised prices due to the tariffs. Experts from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Princeton University, and Columbia University reported tariffs from 2018 increased costs for consumers by $1.4 billion per month. Many of the goods affected were “part of the daily lives of American consumers,” including soap, lithium batteries, washers and dryers, clothing and shoes, and electronics.

Despite the summer tariff exchange, the U.S. and China agreed to keep negotiating. Both countries imposed another round of tariffs in September, but on December 13, 2019, officials on both sides announced they had reached a preliminary agreement. The deal, referred to as “Phase One,” (to be supplemented by more negotiations in the future, called “Phase Two,” which have not officially occurred as of late 2021) was signed on January 15, 2019.

- Tariffs

The U.S. did not impose a 15% tariff scheduled to go into effect in December 2019 on Chinese goods and will cut the 15% tariff rate imposed on September 1, 2019 in half. China also cancelled a 25% tariff set to impact U.S.-made cars. In February 2020, China announced it would be cutting 10% and 5% tariffs imposed in September and December in half, and the U.S. responded by announcing it would also cut tariffs in half on $120 billion of goods.

- Trade Deficit

China agreed to increase its purchases of American products by $200 billion over 2 years. This includes approximately $54 billion in energy purchases, $78 billion in manufacturing purchases, $32 billion in farm products, and $38 billion in services. This is a big deal in particular for farmers, who have been hit “at every single angle” by the trade war. According to the Farm Bureau President, “China was once the largest market for U.S. agricultural products but has dropped to fifth largest since retaliatory tariffs were introduced. This agreement will help turn around two years of declining agricultural exports.”

- Intellectual Property

The agreement included stronger legal protections for patents, trademarks, and copyrights, as well as improved procedures to combat online infringement, counterfeiting, and pirating. China has also agreed to “eliminate any pressure for foreign companies to transfer technology to Chinese firms as a condition of market access…and to eliminate any government advantages for such transfers.”

- Financial Services

U.S. companies will have improved access to China’s banking, insurance, securities, and credit rating services, a lack of access to which has proven to be an investment barrier in the past. Many business people maintain this will need to be further addressed in future negotiations, as the Chinese market is so heavily dominated it is “hard to see how (U.S. firms) might be able to compete.”

What will need to be addressed in “Phase Two” agreements?

- Remaining Tariffs

Tariffs remain on 75% of Chinese imports to the U.S. There are full tariffs on $250 billion worth of Chinese products and reduced tariffs on another $120 billion of goods. On average, tariffs on both sides are still up 20% from pre-trade war levels. There is no timeline for reducing or removing these tariffs as they will likely be part of Phase Two negotiations, but there is also concern they could “cloud prospects for growth in business investment between the two countries.”

There are no agreements to eliminate the subsidies China grants to its domestic companies, nor does the agreement mention oversight of Chinese state-owned firms. The agreement put in place a framework for implementing dispute resolution offices that could address these issues in the meantime, although there are no clear details as to how these offices will function and be monitored.

- U.S.-China Technology Rivalry

Made in China 2025, a plan designed to help Chinese companies become global leaders in emerging technologies, was not addressed in the agreement. There was also no mention of Huawei, the Chinese technology company that has frequently found itself in the center of the U.S.-China technology rivalry.

See here for a full timeline of the US-China Trade War. See the entire agreement here.

Results

One year after the initial signing, experts credit the Phase One Agreement with improving business conditions for some American companies. In exchange for some tariff cuts, China has improved access to its markets – particularly financial markets – for U.S. companies. Many tariffs, however, still remain, and some U.S. businesses are claiming they take a significant portion of profits and are creating job losses. The CATO Institute reports surveys show 65% of American companies have been negatively impacted by the remaining tariffs, including 39% who experienced loss of sales due to tariffs. Only 7% think the benefits of the agreement outweigh the costs. The U.S. Customs and Border Protection reported it collected almost $75 billion in tariffs on imported goods during FY2020, and a recent study by economists from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York found that these tariffs are “almost entirely borne by U.S. firms and consumers.”

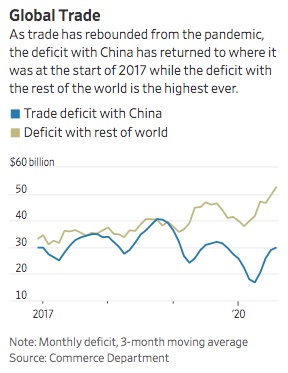

After widening in 2018 to $419 billion, the U.S. trade deficit with China saw a reduction in 2019. The trade gap totaled $311 billion in 2020, and widened 14.5% to $355 billion in 2021 due to increased American demand for imported goods.

The combined U.S. goods and services trade deficit has substantially increased over the past few years; it was $481 billion in 2016, $679 billion in 2020, and reached $859 billion in 2021. U.S. exports did increase by 18.5%, but not as much as the 20% increase in imports. Mary Lovely, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, explains that the “‘tariffs on China reduced imports from China, but these were mostly replaced with imports from other sources.’” Trade deficits with Vietnam, Thailand, Taiwan, Philippines, and some European countries were all higher in 2020 than they were in 2019, but trade for 2021 trade with these countries decreased as trade with China resumed.

For 2021, U.S. capital flows appear to be on the rise, returning to pre-tariff levels of 2018, which has garnered concern among policymakers and businesses. In late 2021, China began “blurring the lines between ostensibly private Chinese companies and those that are officially state-run by the Chinese Communist Party,” meaning U.S. businesses need to be aware that “‘their participation in the Chinese economy is conditioned by the [Chinese Communist Party]’s policy priorities and subject to its control.'”

China’s commitment to increase its purchases of U.S goods fell short for 2020. China agreed to purchase $159 billion in U.S. goods by the end of 2020, but had only purchased $110 billion by the end of December 2020. As of March 2021, “China is once again the U.S.’s chief customer for agricultural goods,” according to the Wall Street Journal. In the first 8 weeks of 2021, China purchased almost triple the amount of U.S. soybeans compared to the first 8 weeks of 2020. Still, as of February 2022, China had only bought 57% of the American exports it had committed to purchase.

Replacing NAFTA

While the focus has mainly been on China, the U.S. House of Representatives, the Trump Administration, labor unions, and the governments of Canada and Mexico were working on the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) to replace the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). After “intense negotiations,” the deal passed in the U.S. House of Representatives and U.S. Senate before being signed by former President Trump in January 2020. Mexico and Canada have also approved the deal.

The USMCA includes provisions to create more manufacturing jobs and new rules in the automotive sector, as well as provisions “that reduce policy uncertainty about digital trade” and international data transfers. See the full fact sheet here. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce supports the USMCA’s provisions to support new technologies in trade, including digital trade in safely and securely moving data across borders, biotechnology trade in the realm of agriculture, and intellectual property protections. Although some workers unions are still opposed, the deal’s provisions to enforce labor standards has the support of the AFL-CIO.

Such commitments to open flows of data across international borders are predicted to increase trade with USMCA partners as well as the rest of the world. Other trade issues addressed, including workers’ rights, will also positively impact output, exports, wages, and employment across industries. The US International Trade Commission predicts the USMCA will increase U.S. employment by 176,000 jobs (0.12%) and raise U.S. GDP by about $68 billion (about 0.35%).

Find out and share how tariffs impact a local business in your community. Find out trade facts for your state with this interactive map from USTR. Plan a Circle Meeting to discuss Tariffs and be sure to include the Policy Circle Brief on U.S. Foreign Policy Asia Pacific as part of your conversation.