A series of crises around the globe - from Afghanistan and Ukraine to Syria, Yemen, and Venezuela - have resulted in the largest refugee population since WWII. America's refugee policies are a key component of our immigration laws, which are frequently debated but rarely updated in meaningful ways. How does the U.S. welcome and support individuals and families that arrive in the U.S. seeking to build new lives? What are the legal differences between a refugee and an asylum seeker? How has the refugee population grown and changed in recent decades? What roles do businesses, communities, and nonprofits play in supporting these groups? What role does the government and legal system play in shaping existing policies and the path forward? What can citizens do to address refugee crises?

Introduction

Watch The Policy Circle’s Move the Needle on Responding to Refugee Crises to hear from Jennifer Simon (USA for UNHCR), former Green Beret Scott Mann (Task Force Pineapple), and Natalie Gonnella-Platts and Laura Collins (George W. Bush Institute) as they share unique perspectives and critical insights on unfolding humanitarian crises:

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

Case Study

“The impossible happens every day in the life of a refugee.” – Kao Kalia Yang

Kao Kalia Yang was born in a Hmong refugee camp in Thailand in 1980, but her story began years earlier. Her parents met and married in the jungles of Laos in 1978. They were among the thousands fleeing the Hmong genocide in Laos. In 1975, after the U.S. retreated at the end of the Vietnam War, the Hmong population was targeted when Laos was left under communist control. Her parents and her young sister fled imprisonment in Laos and crossed the Mekong River into Thailand.

In 1987, at age six, Kalia and her family arrived in America’s heartland, as refugees. Shortly after she arrived in Minnesota, at age seven, she stopped speaking English in public, but she found her voice elsewhere. As she told Minnesota Public Radio, “When I tried to speak, kids laughed. So I stopped completely. But I was a kid and the words had to go somewhere. So they went onto the page. … On the page, I got more tries, so my voice grew strong, and it grew natural.”

Growing up her father told her that he wanted her to become a doctor or lawyer. “Lawyers can protect the rights that we’ve never had enough of; doctors can heal what is broken in the bodies around us,” he told her. After her sister won a spelling bee a year and a half after their arrival, it was decided that she would become the lawyer and Kalia would be the doctor. It was not until her final year as pre-med student at Carleton College that she dedicated to pursue her dream of writing after receiving a fellowship to attend Columbia University’s MFA creative writing program.

Today, Kalia is an author, filmmaker, public speaker, and teacher living in St. Paul, Minnesota, with her husband and their three children. She has taught at K-12 institutions and universities across the country, and authored five children’s books and four award-winning books for adults.

She explains her experiences in her TED talk (14 min):

Why it Matters

Conflicts, unrest, and disasters around the world have resulted in over 84 million displaced individuals worldwide, 26.6 million of whom are refugees. This estimate from mid-2021 does not account for the 80,000 Afghan refugees evacuated to the U.S. from Kabul or the over 6.5 million refugees fleeing the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

As a member of the UN, the U.S. signed the United Nations 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and annually accepts refugees designated by the UN High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR). Working with other nations and international partners to address migration and eliminate the driving factors that force people to seek refuge is an important part of U.S. foreign policy that shapes our relationships with our allies and influences others to take action.

America prides itself on being a nation of immigrants and serving as a haven for those fleeing persecution and seeking a better life. But the process for both refugees and asylum seekers – who have left their lives behind, frequently come with very few belongings, and may not speak the language – is a long one. Let’s unpack the process and challenges so we can better understand and engage. Community support is key for new arrivals, whose integration affects the social fabric, public health and education systems, and local economy of the established welcoming community.

Putting it in Context

Definitions

The term “migrant” is not defined under international law, but it is generally understood to mean anyone staying outside of their country of origin who is not an asylum-seeker or refugee.

International Law

According to the United Nations 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees (1951 Refugee Convention), the legal definition of a refugee is a person who has fled his or her country and is unable or unwilling to return to that country because of persecution, or a well-founded fear of persecution, based on:

- Race

- Religion

- Nationality

- Membership of a particular social group

- Political opinions

The 1951 Refugee Convention (and its 1967 Protocol) are the key legal documents that protect refugees from being returned to the countries where they risk being persecuted. Countries that are parties to the Refugee Convention are obligated under international law to provide certain resources and protections to those who are granted refugee status.

Asylum seeker is the term for anyone seeking protection in a different country than their own because of a well-founded fear of persecution in their home country. Asylum seekers have not yet received any legal recognition of their status. The UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights (Article 14) states that everyone has a right to seek asylum from persecution in other countries.

U.S. Law

The U.S. passed its first refugee-related legislation in 1948 to manage an influx of European refugees following World War II. The U.S. accepted refugees throughout the Cold War, but “legislation that authorized acceptance of refugees was passed primarily on an ad hoc basis, responding to ongoing mass migrations.”

When the U.S. began admitting hundreds of thousands of refugees after the fall of South Vietnam in 1975, Congress standardized the system. The Refugee Act of 1980 established formal refugee and asylum programs in the U.S., and brought U.S. law into greater alignment with the UN Refugee Convention. The U.S. follows the UN definitions of refugees and asylum seekers regarding fear of persecution, but there is a difference in how the U.S. processes refugees and asylum seekers.

In the U.S., the main difference between refugees and asylum seekers is the location of the person at the time of application. Asylum seekers submit their applications either when present in the U.S. or at a U.S. port of entry, such as a border station at a land border crossing or an international airport.

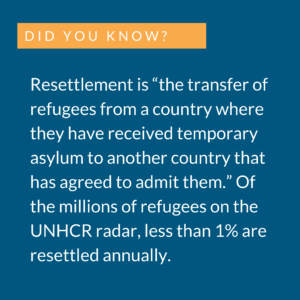

For refugees, UNHCR determines “whether a person seeking international protection is considered a refugee under international, regional, or national law.” If considered a refugee, the UNHCR can help resettle them. This means that refugees come from abroad, rather than submitting an application in the U.S. or at a port of entry. Refugees do not submit applications directly to the U.S., nor can they choose which country UNHCR will ask to consider their case, although they can decide whether or not they wish to be resettled. The process for both refugees and asylum seekers is explained in detail in the “Process” section below.

For refugees, UNHCR determines “whether a person seeking international protection is considered a refugee under international, regional, or national law.” If considered a refugee, the UNHCR can help resettle them. This means that refugees come from abroad, rather than submitting an application in the U.S. or at a port of entry. Refugees do not submit applications directly to the U.S., nor can they choose which country UNHCR will ask to consider their case, although they can decide whether or not they wish to be resettled. The process for both refugees and asylum seekers is explained in detail in the “Process” section below.

U.S. law also provides other humanitarian pathways that prevent individuals from being detained or deported based on their immigration status in the U.S. For example, the U.S. grants immigration protection to victims of human trafficking through T Visas, and to crime victims who have suffered mental or physical abuse through U Visas, which allows these victims to assist in investigations into the trafficking or crime.

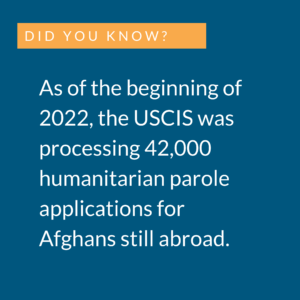

Specific Special Immigrant Visas have been granted to Iraqi and Afghan translators and interpreters, although in the case of Afghan evacuees there have been delays in processing. The vast majority of Afghans fleeing Afghanistan after the Taliban took control were brought to the U.S. under humanitarian parole.

Humanitarian parole “allows an individual who may be inadmissible or otherwise ineligible for admission into the United States to be in the United States for a temporary period for urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit.” Parole has been used “to provide safe passage for large numbers of people out of conflict zones where the United States had military involvement;” special parole programs include the Cuban Family Reunification Parole Program and the Filipino World War II Veterans Parole Program. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) decides humanitarian parole requests, and those granted parole are eligible to work in the U.S. but are not eligible for any refugee resettlement programs or federal benefits.

Humanitarian parole “allows an individual who may be inadmissible or otherwise ineligible for admission into the United States to be in the United States for a temporary period for urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit.” Parole has been used “to provide safe passage for large numbers of people out of conflict zones where the United States had military involvement;” special parole programs include the Cuban Family Reunification Parole Program and the Filipino World War II Veterans Parole Program. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) decides humanitarian parole requests, and those granted parole are eligible to work in the U.S. but are not eligible for any refugee resettlement programs or federal benefits.

The U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security can also designate a foreign country for Temporary Protected Status (TPS) if the country is facing conditions such as an ongoing armed conflict or an environmental or public health emergency that prevents the country’s nationals from returning safely. Countries granted TPS include Venezuela, Afghanistan, and Ukraine. For more on the crisis in Ukraine specifically, see The Policy Circle’s Ukraine-Russia Brief.

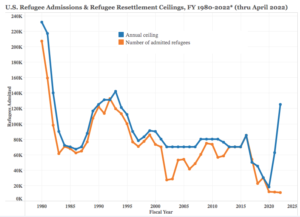

Numbers

Since the enactment of the Refugee Act of 1980, over 3.7 million refugees have resettled in the U.S. Every year, the U.S. government sets a Presidential Determination, capping how many refugees it will accept. This cap averaged between 70,000 and 90,000 from 1999 to 2016. In FY 2017, the Trump administration reduced the cap to 50,000 and suspended the resettlement program.

In FY2020 (Oct 2019 – Sept 2020), there were 11,814 refugees admitted and a cap of 18,000 (the lowest cap since 1980); low numbers were due to bans on refugees from certain countries and cuts to overall refugee admissions prior to the pandemic, and then due to travel restrictions and the temporary suspension of the worldwide refugee resettlement program in response to COVID-19. In FY2021 (Oct 2020 – Sept 2021), 11,411 refugees resettled in the U.S.

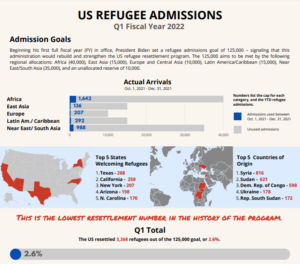

The Biden administration raised the cap from 15,000 to 62,500 for FY 2021, and for FY2022 (Oct 2021 – Sept 2022), raised the cap to 125,000, allocated by region as follows:

- Africa: 40,000

- Near East / South Asia: 35,000

- East Asia: 15,000

- Latin America / Caribbean: 15,000

- Europe 10,000, and

- 10,000 in unallocated reserves.

Refugee Council USA breaks down arrivals for the first quarter of FY2022 (Oct 1, 2021 – Dec 31, 2021). The almost 75,000 Afghans that the U.S. evacuated in 2021 are not included in this number, as they were admitted to the U.S. under humanitarian parole.

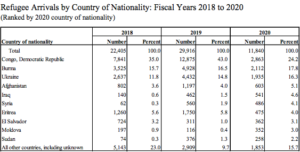

The following chart breaks down the top ten countries of origin for refugee arrivals in the U.S. between for 2018, 2019, and 2020:

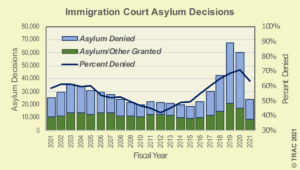

The asylum system also reviewed fewer cases due to partial court shutdowns in response to COVID19. In FY2020 (Oct 2019 – Sept 2020), immigration courts decided over 60,000 cases; in FY2021 (Oct 2020 – Sept 2021), this number fell to under 24,000. Case increases since 2017 have mainly been driven by insecurity and instability in Northern Triangle countries (El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras), which account for 52% of asylum applications.

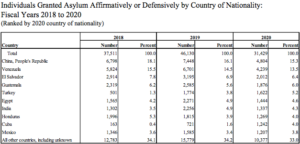

The top countries of origin for refugees and the top countries of origin for asylum seekers have only one country (El Salvador) in common, as indicated in the chart below:

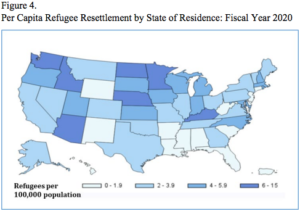

This chart from the Department of Homeland Security breaks down per capita refugee resettlement in the U.S.:

In 2020, 56% of admitted refugees were resettled in the top ten resettling states: California, Washington, Texas, Idaho, New York, Michigan, Kentucky, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Arizona, and Ohio.

Refugees and asylum seekers have some of the highest naturalization rates of all immigrants (Naturalization is the process of becoming a U.S. citizen for those born outside of the U.S.) Between 2000 and 2013:

- Of the roughly 600,000 adults who obtained Lawful Permanent Residence (LPR, aka “green card” holders) based on prior admission as a refugee:

- 49% naturalized within five years

- 57% naturalized within six years.

- For comparison, of the 10.8 million non-refugee adult immigrants who obtained LPR status:

- 12% naturalized within five years

- 29% naturalized within six years.

Among asylum seekers, 90% of those granted affirmative asylum between 2009 and 2017 gained LPR status by the end of 2019.

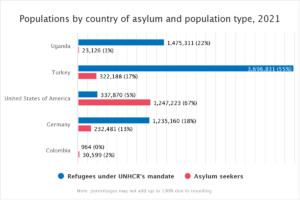

The following chart breaks down the countries with the largest asylum and refugee populations to give an idea of international comparisons:

The Role of Government

Federal

Article I, Section 8, clause 4 of the Constitution entrusts the federal legislative branch with the power to “establish a uniform Rule of Naturalization.”

Specifically, Congress is responsible for crafting the laws that determine how and when noncitizens can become naturalized citizens of the United States. But control over naturalization does not necessarily mean control over immigration, meaning “the federal government is not explicitly granted a general power to exclude or remove noncitizens from the United States.” For the first century after the nation’s birth, many states enacted laws regulating and controlling immigration across their own borders. It was not until the late 19th century that Congress began to actively regulate immigration on a national level, and it was not until 1980 that Congress enacted a specific program for refugees and asylum seekers.

Every year, U.S. immigration law (namely, the Immigration and Nationality Act, INA) requires officials in the executive branch to review the global situation of refugees and consider the extent of participation by the U.S. in resettling refugees. In consultation with Congress, the President sets the refugee cap and regional allocations for all refugees for the upcoming fiscal year. There is also an unallocated reserve included in the total, in case more refugees from a certain region need to be admitted due to unforeseen circumstances.

Congress

The Senate Judiciary Committee Subcommittee on Immigration, Citizenship, and Border Security, and the House Judiciary Committee Subcommittee on Immigration and Citizenship have jurisdiction over:

- Immigration, citizenship, and refugee laws;

- Admission of refugees;

- Oversight of immigration functions within the Department of Homeland Security and the Department of Justice;

- Treaties, conventions, and international agreements related to migration.

The Refugee Act mandates the President consult with the Senate and House Judiciary Committees before setting total refugee caps and regional allocations.

The Executive Branch

A number of federal agencies are involved in making and overseeing refugee and asylum policy. For example, many agencies are involved in the United States Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP). USRAP agencies include the Department of State, the Department of Homeland Security, and the Department of Health and Human Services. In particular, the agencies with the most responsibility are:

- The Department of State, from where a majority of funding for refugees comes from.

- The Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration (PRM) is the humanitarian bureau of the State Department. It has overall USRAP management responsibility overseas and takes the lead in proposing refugee admissions ceilings and processing priorities. Most of the State Department funding for refugees is managed by PRM.

- The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), which provides social services for refugees. These services are managed by the Administration for Children and Families (ACF).

- The Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) under ACF is the specific office that provides domestic social and health services to refugees, asylum seekers, special immigrant visa holders, unaccompanied children, and victims of trafficking.

- The Department of Homeland Security secures the U.S. air, land, and sea borders, which includes monitoring who is crossing the border and entering the U.S.

- U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) is responsible for adjudicating refugee and asylum applications, as well as screening refugees. The Bureau of Customs and Border Protection (CBP) also screens refugees at ports of entry.

- The Department of Justice enforces U.S. law, which includes immigration laws.

- The Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) conducts immigration court proceedings, part of which includes defensive asylum cases.

Funding for these agencies includes:

- $3.85 billion from the State Department’s Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration and USAID dedicated to humanitarian assistance for refugees and the USRAP program (FY2022);

- $4.4 billion for refugee programs managed by the Administration for Children and Families (FY2022, after operating with less than $2 billion for FY2020 and FY2021).

- $360 million for Asylum, Refugee and International Operations under USCIS (FY2022);

- Funding is historically low because USCIS’s main funding comes from its application fees rather than appropriations;

- $734 million for EOIR (FY2021).

State/Local

While management and funding of refugee-related programs and services comes from the federal government, implementation is the responsibility of states and localities. For example, states administer funding from the Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR), primarily in the form of grants, and coordinate refugee-funded services with other programs administered at the local level, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).

ORR partners include state and county refugee programs, local resettlement agencies, and community social service agencies. At the local level, these agencies provide short term case and medical assistance, employment training and opportunities, English as a Second Language (ESL) classes, and case management services.

Find ORR key state contacts and resources in your state.

When refugees arrive, states and localities must consider community factors including family ties, health care services, housing availability, education and job opportunities, and cost of living. In recent years, “some states and localities have become increasingly vocal about having greater input in the resettlement process, citing concerns such as limited federal funding, use of local resources, and potential national-security threats.”

Private Sector

Federal, state, and local governments rely on non-governmental partners to provide resettlement assistance and services to arriving refugees.

At the international level, Resettlement Support Centers process refugee cases and coordinate administration of the refugee program. The Department of State funds and manages seven support centers around the world, which are operated by non-governmental organizations, international organizations, or U.S. embassy contractors. Travel arrangement and medical screenings for admitted refugees are usually coordinated by the International Organization of Migration.

Domestically, a number of nonprofits provide resettlement assistance and services to arriving refugees through government contracts. There are nine main resettlement agencies that are contracted with the federal government to resettle refugees. Through these public-private partnerships, the nine domestic resettlement agencies handle the logistics of refugee resettlement. Representatives of the organizations meet with and review biographical data of refugees to determine where the refugees should be settled. Resettlement agencies consult with law enforcement, emergency services, public schools, and local authorities as part of the process. See which ones operate in your state.

A number of smaller organizations like Exodus World Service, Catholic Charities and HIAS provide community services for arriving refugees and seek to engage other community members, such as through welcome circles. For example, Welcome.US and Refugee Council USA are coalitions of US-based organizations, as well as businesses, who advocate for and with refugees. Upwardly Global and Businesses for Refugees seek to eliminate employment barriers for refugee professionals and incorporate their skills in the economy. Private sector companies are also involved in these endeavors to provide services to refugees, such as Uber’s program to train and hire refugees.

Process

The U.S. has two separate programs:

- One refugee program for those outside the U.S. and their eligible relatives

- One asylum program for those physically present in the U.S., or arriving at one of the 328 U.S. ports of entry, and their eligible relatives.

These programs are part of the U.S. immigration system, but the processes are very different from other legal immigration pathways, such as for family reunification or employment purposes. The refugee and asylum programs are only for specific individuals who have qualified on humanitarian grounds.

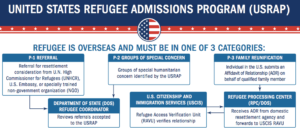

Those who are eligible are considered based on processing priorities:

- Priority 1 (P-1): Individuals referred by the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR), a U.S. embassy abroad, or certain Non-governmental organizations (NGO)s.

- Priority 2 (P-2): Groups of special humanitarian concern (for example, individuals in Afghanistan who had worked for or on behalf of the U.S. government or its coalition partners).

- Priority 3 (P-3): Family reunification

Refugees

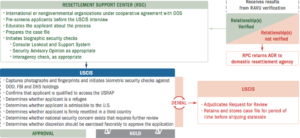

Refugees apply for consideration to be resettled in the U.S. from outside of the U.S. They must receive a referral in order to do so. The process of vetting refugees is very different from the rest of the U.S. immigration system, and is a lengthy one. From the start of background checks to eventual resettlement the entire process for a refugee takes 18-24 months. During this process, the UNHCR:

- Registers and interviews refugees;

- Takes biometric data and background info;

- Determines if the person is eligible for protection based on national or international law;

- Refers the person to other countries for consideration (if eligible).

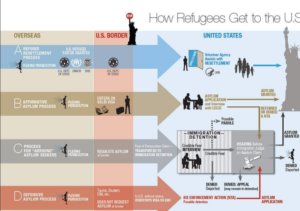

The following diagram illustrates this process:

The U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP) is an interagency effort that involves multiple government and non-government partners from abroad (such as the UNHRC, which refers cases to the U.S., and Resettlement Support Centers) and within the U.S. (such as the state and local resettlement organizations that work with the Department of State and carry out administrative functions).

If referred to the U.S., individuals can fill out an application. They are screened by Resettlement Support Centers and the U.S. government, which includes:

- An interview with the a refugee officer from the Department of Homeland Security while the refugee is still abroad;

- Biographic and biometric background checks and screenings by:

- The Department of Homeland Security;

- The FBI;

- The Department of Defense; and

- The National Counterterrorism Center, which also checks international watch lists and Interpol database.

Approved refugees travel to the U.S., where they have a full screening upon arrival in the U.S. by the Transportation and Security Administration (TSA) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP), and are assisted by domestic resettlement agencies:

After resettlement, refugees may:

- File a relative petition for a spouse or dependents within 2 years;

- Work immediately upon arrival in the U.S.;

- Receive federal student financial aid;

- Join certain branches of the U.S. armed forces;

- Are eligible for cash assistance (for up to 12 months) if ineligible for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF); and

- Are eligible for medical assistance (for up to 12 months) if ineligible for Medicaid.

Refugees must apply for Lawful Permanent Residence (LPR) status (aka a “green card”) after one year. LPRs may apply for U.S. citizenship (naturalization) after five years.

World Exodus explains the journey of refugees (2 min):

Asylum Seekers

Asylum seekers apply for asylum either from within the U.S. or at a U.S. port of entry. There are two separate paths for seeking asylum in the U.S.: affirmative and defensive.

Affirmative Asylum Processing with USCIS

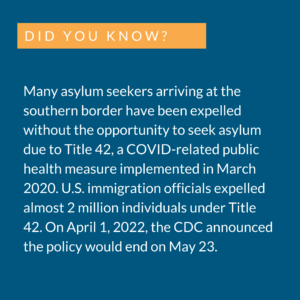

Asylum seekers must apply for affirmative asylum within one year of arriving in the U.S. or at a U.S. port of entry. In the U.S., the majority of asylum seekers arrive at the southern border. An asylum officer from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) evaluates the individual’s testimony and application, and also considers the conditions of the country from which the asylum seeker originates. Asylum seekers may apply for employment authorization one year after filing their asylum application.

If granted asylum, grantees:

- Are immediately authorized to work;

- May file a relative petition for a spouse or dependents within 2 years;

- May apply for a green card after one year;

- Are granted a Social Security Card (with employment authorization);

- Are eligible for cash assistance (for up to 12 months) if ineligible for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF);

- Are eligible for medical assistance (for up to 12 months) if ineligible for Medicaid; and

- Are eligible for employment assistance (for up to 5 years).

Defensive Asylum Processing with EOIR

The Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR), under the Department of Justice, handles the defensive asylum system. This process begins one of two ways:

- A potential candidate is referred to an immigration judge by USCIS after having been determined to be ineligible for asylum at the end of the affirmative asylum process;

- A potential candidate is placed in removal (deportation) proceedings after being apprehended in the U.S. or at a U.S. port of entry without proper documentation, but were found to have credible fear of persecution (as determined by an asylum officer).

Immigration judges hear defensive asylum cases in courtroom proceedings, which includes testimony from asylum seekers (and their attorneys, if they have one), and the U.S. government. The immigration judge decides if the asylum seeker is eligible for asylum. If deemed inadmissible to the asylum system, the judge determines if they are eligible for other forms of relief from removal.

The following chart summarizes the refugee and asylum processes:

USA Today breaks down how refugees and asylum seekers can resettle in the U.S. (3 min):

Challenges & Areas for Reform

Increasing Number of Displaced People Worldwide

Increasing Number of Displaced People Worldwide

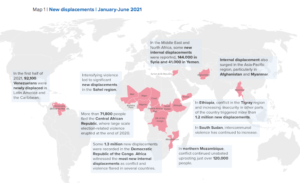

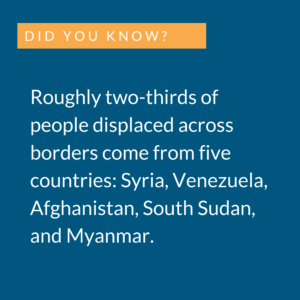

In mid-2021, the UN estimated there were 84 million forcibly displaced people worldwide due to armed conflicts, widespread violence, and human rights violations. Broken down, this amounts to 26.6 million refugees, 4.4 million asylum seekers, and 50.9 million Internally Displaced Persons.

In May 2022, the UN estimated that there were more than 100 million forcibly displaced people worldwide, up from 84 million in mid-2021. This number includes refugees, asylum seekers, and Internally Displaced Persons. The record high represents 1% of the global population and is equivalent to the 14th most populous country in the world.

These numbers have been steadily increasing since about 2012, mainly driven by fragile and conflict-affected areas. Natural disasters have added to these strains; for example, fighting in Yemen has internally displaced 4 million people in Yemen, where famine has exacerbated conflict. Since the February 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, at least 6.5 million Ukrainians have fled to neighboring countries, and more than 7 million Ukrainians are internally displaced.

It is extremely difficult, even with international coordination, to address the ongoing conflicts that are driving displacement. Conversations about accepting and admitting refugees usually revolve around how countries can manage migration on their own terms. Host countries are concerned with the social and economic fabric of existing communities, and how to integrate refugees, which means legislation regarding refugees usually starts at a country’s border. This has made it difficult to implement certain international frameworks such as the UN Global Compact on Refugees, which provides participating countries with “a blueprint for governments, international organizations, and other stakeholders to ensure that host communities get the support they need and that refugees can lead productive lives.”

International development organizations, both non-governmental and those associated with governments, make efforts in this area. For example, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) frequently works with the private sector to address economic, security, environmental, and governance challenges. USAID launched the Northern Triangle Task Force in May 2021 to address the causes of irregular migration that are driving thousands of migrants to the U.S. southern border. Still, addressing these root causes – from government corruption and crime to the effects of climate change and lack of educational opportunities – is no small feat.

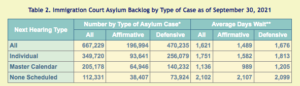

U.S. Focus: Backlogs of Asylum Cases

Driven primarily by the number of arrivals at the southern border, the U.S. faces a substantial backlog of asylum cases. According to Syracuse University’s tracker, roughly 40% of asylum cases in immigration court filed since 2000 are still pending. Shutdowns due to COVID-19 only exacerbated the existing bottlenecks: USCIS faced a backlog of almost 400,000 cases as of mid-2021, and immigration courts faced a backlog of over 670,000 cases as of 2022.

Additionally, credible fear claims rose from roughly 14,000 in FY2012 to over 100,000 in FY2019. Most migrants taken into custody at the border lack documentation, and if detained are subject to expedited removal. If they express fear of returning to their home country, they are referred for a credible-fear interview with a USCIS asylum officer. If asylum officers are addressing credible fear cases, they are not addressing affirmative asylum cases, adding to the backlog.

The issue is that U.S. law requires asylum cases to be processed within 180 days. If an asylum case passes the 180 day mark without a decision, employment authorization documents are automatically approved for the individual with the pending case. For context, USCIS has been sued in the past over slow processing, and the average wait time for case resolution in immigration court is between four and five years. Not only is this simply a backlog that drains resources from U.S. agencies and leaves asylum seekers in limbo, but it makes it difficult to identify those with legitimate cases. As described by the Migration Policy Institute, “as processing times have grown, so too have incentives to file claims as a means of obtaining work authorization and protection from deportation, without a sound underlying claim to humanitarian protection.”

Some proposed reforms to address backlog include:

- Moving case determinations for defensive asylum from immigration courts to the USCIS Asylum division

- Immigration court is more resource-intensive, requiring an immigration judge as well as clerks and support staff, whereas trained asylum officers’ sole responsibility is asylum adjudications.

- Hiring freezes, budget cuts, and pandemic-related budget shortfalls forced USCIS to furlough 13,000 employees by the end of 2020, but the agency has been in the process of hiring and training more employees.

- Immigration court is more resource-intensive, requiring an immigration judge as well as clerks and support staff, whereas trained asylum officers’ sole responsibility is asylum adjudications.

- Modernize systems and data analysis

- Data sweeps through backlogs can help identify cases for expedited processing, or cases where USCIS does not have jurisdiction.

- Centralized case vetting before interviews

- Background checks and security analysis at a central USCIS office would remove additional work from asylum offices in the field. Field officers can interview and complete cases rather than spend time on pre-interview background checks.

Impact on Local Communities

Hospitality towards migrants is a core national value in many countries, but polling indicates “countries that have initially welcomed large influxes of migrants or refugees may reach a tipping point,” particularly if the public perceives an endless wave of migration that has been poorly managed.

It is not uncommon for local residents to express concerns about incoming refugees, such as whether refugees will put additional pressure on welfare programs, or will be competing for scarce jobs. This is particularly the case in communities where residents are aware that pressure on the job market and funding for services already exists.

Drain on Services

Evidence suggests that refugees do not consume considerable amounts of welfare funding. A 2018 study by CATO Institute found that the average value of welfare benefits per immigrant (which included lawful permanent residents, guest workers, temporary migrants, refugees, asylees, and illegal immigrants) amounted to $3,718 in 2016, versus the $6,081 average value of welfare benefits per native U.S. citizen, meaning immigrants consumed 21% less benefits than native-born Americans on a per capita basis.

This held when the study was updated in 2022 with 2019 data; as of 2019, immigrants consume 28% less welfare and entitlement benefits than native-born Americans per capita, with the average welfare benefits per immigrant amounting to $5,778 and the average value of welfare benefits per native-born American amounting to $8,012.

The studies also found that while immigrants consume more than native U.S. citizens in some categories (SNAP and Medicaid in 2016, and WIC in 2019), this consumption is offset by the fact that native U.S. citizens consume significantly more than immigrants in Medicare and Social Security retirement benefits. (Medicare and Social Security are key drivers of the U.S. debt – read more about these two programs in The Policy Circle’s Federal Debt Brief or Safety Net Programs Brief.)

Additionally, on an international level, only about 1% of refugees resettle in third countries; most remain in their initial country where they applied for refugee status. This means the bulk of integration challenges and responsibilities falls on developing countries. For example, roughly 40% of worldwide refugees are hosted in just five countries:

- Turkey (next to Syria, from where the most refugees originate);

- Colombia (next to Venezuela, from where the second largest number of refugees originate);

- Uganda (next to South Sudan, from where the 4th largest number of refugees originate);

- Pakistan (next to Afghanistan, from where the 3rd largest number of refugees originate);

- Germany (a result of Germany’s 2015 decision to admit one million refugees).

*Additionally, Poland hosts 3.5 million Ukrainians who have fled Ukraine since February’s Russian invasion.

Employment

Despite experience, certifications, and eligibility for employment support, refugees are less likely to be employed the longer they live in the U.S., and research suggests the reason is mainly due to public policies. Researchers from Cornell University found that “‘declines in federal funding support, market-based mandates emphasizing rapid employment and quickly achieved self-sufficiency, and a patchwork of disparately funded and poorly networked support organizations’” explained why long-term employment prospects are not impressive.

Based on the research, it appears that emphasis on quick integration and achieving self-sufficiency result in refugees being “funneled into low-paying jobs that do not offer long-term sustainable employment,” instead of “being given the time to learn English and find jobs that match their skills and abilities,” or, as is often the case, to get relicensed upon arrival in the U.S.

A number of actors in the private sector are already working in this realm for skills assessment, training, and job placement opportunities so refugees can best integrate into the economy. For example, Upwardly Global, which seeks to advance refugees’ and immigrants’ incorporation into local communities and economies, partnered with Coursera for Refugees. The partnership offers refugee job seekers online classes free of charge, helping refugees increase their technical skills in their fields and making them more marketable. Upwardly Global recommends investment in workforce development programs, such as:

- Supporting refugees who face logistical challenges such as taking care of dependents or lacking transportation;

- Providing advanced English as a Second Language classes geared towards workplace fluency;

- Fast-tracked programs to help those with experience and credentials gain the necessary certifications;

- Incentivizes for employers to educate themselves and their employees on foreign degrees or work authorizations – such as volunteer networking events or information sessions – to increase professional opportunities for, and eventual hiring of, skilled refugees.

In another example, the ride-sharing service Uber has partnered with the Tent Coalition for Refugees in the U.S. and has committed to making 1,000 refugees drivers on its platform in Africa by 2022. Uber is also partnering with Tent to assist refugees with the costs of leasing a car and with Uganda-based PostBank, which will offer loans at what it terms “competitive rates.”

Like all workers, refugees have just as much ability to contribute to the economy through innovation, entrepreneurship, and consumption. They also contribute by paying taxes; a draft report by the Department of Health and Human Services in 2017 found that refugees in the U.S. contributed $63 billion more in government revenues than they cost, contributing an estimated $270 billion in tax revenues to all levels of government between 2005 and 2014. Based on one estimate from the Center for Global Development, if U.S. refugee admissions from 2017 to 2021 had not dropped and instead remained at 2016 levels, the U.S. economy would have gained an additional $9.1 billion each year, and public revenues at the federal, state, and local levels would have increased by over $2 billion each year.

Community Integration

Moving to a new country can be a challenge for those who choose to do so willingly; in the case of resettling refugees, who may have fled their country of origin quickly and with few belongings, this can be even more difficult. Language barriers and limited networks are only the start. For example, an unexpected obstacle for thousands of Afghan refugees leaving military bases to start rebuilding their lives in the U.S. has been the state of the housing market. In big cities, rentals are plentiful but the costs are too high; in small towns, prices are more manageable but inventory is limited.

Given how tight the market is, landlords and property managers can afford to be picky, and “have been reluctant to take a chance on foreigners who still lack jobs and permanent residency status, and who often have large families.” Carina Black, executive director at the Northern Nevada International Center, says that in Reno (where the average apartment rents for $1,600), Afghans are being placed in motels, mother-in-law suites, and Airbnbs.

Local resettlement agencies are key to helping refugees integrate in communities. Catholic Charities, a national nonprofit that is one of the resettlement agencies working directly with the U.S. government, has helped in the process of moving Afghan refugees from military bases to join new communities across the U.S.. Working closely with community partners, resettlement agencies like Catholic Charities find families permanent housing and work suitable for their skills, assist with enrolling children in schools, and offer cultural and employment orientation classes.

Still, these agencies are struggling. They receive small stipends from the U.S. State Department, but have been underfunded in recent years, meaning the burden tends to fall on the local communities. For example, Catholic Charities of the Archdiocese of Oklahoma city reports every home refugees have moved into in the area has been completely sponsored by donors in the local community.

Additionally, after an almost full stop on refugee admissions due to the pandemic, these agencies have suddenly been asked to rapidly expand their capacities. Particularly since mid-2021, as the U.S. government works to resettle almost 80,000 Afghans evacuated from Kabul, caseworkers have seen caseloads 4-5 times greater than what they normally handle. Nationally, agencies are asked to resettle fewer than 45,000 refugees annually, compared with over 75,000 Afghan evacuees within a few months. These caseloads make it difficult to address the challenges of rebuilding and modernizing the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program that saw years of funding cuts prior to the pandemic.

Conclusion

The U.S. has systems to welcome and support individuals and families that arrive seeking to build new lives, but global events are challenging the systems currently in place. From a rapid increase in the number of applications for refugee resettlement and asylum, to long-existing backlogs and the difficulties of integrating newcomers into new communities, there are obstacles at the international, national, and local levels. Policymakers, businesses, communities, and nonprofit organizations all play a role in designing policies that will support newcomers, the communities in which they may live, and the nation as a whole.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Find out what your state and city are doing about welcoming refugees.

- Do you know where refugees are located in your state or city?

- Is there a nearby military base that has housed refugee families?

- How are refugees integrated into the community?

- What projects and agencies exist, or does one need to be formed?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- What are the local agencies working with refugees in your state or city? The Office of Resettlement of Refugees at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) provides a list.

- What organizations work with refugees in your state or city?

- In response to population declines and related worker shortages in Brattleboro, Vermont, the Welcoming Communities group in the Brattleboro Development Credit Corporation created programs that matched refugees in their communities looking for employment with local businesses looking for workers. The organization helped set up the necessary infrastructure, such as providing transportation and assisting businesses with paperwork, in a model that benefited the entire community.

- What steps have your state’s/community’s elected/appointed official taken?

- Are local representatives particularly involved in welcoming refugees?

- Where do your representatives in Congress stand on accepting refugees?

- How are children of refugees welcomed and integrated in the schools in your district?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with law enforcement, first responders, faith-based organizations, local hospitals, community organizations, school boards, local businesses, etc.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar or look up your local town’ legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, communications@thepolicycircle.org, for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policy makers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Visit an organization that works with refugees, and perhaps offer to help as a mentor, tutor, or just support. For example in Chicago, World Exodus and Catholic Charities have volunteer programs.

- Determine where the gaps are in welcoming refugees in your state or city, or local school and place of worship.

- Speak with business owners about what they may be doing to hire and train refugees

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.