Article III of the Constitution establishes the judicial branch and designates U.S. Congress shall have the power to establish district courts and courts of appeal. Once these courts are established, they require judges to conduct courtroom proceedings. Judges adjudicate legal cases, but how are judges selected and appointed?

Why it Matters

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

Due to our important role in voting for candidates for the executive and legislative branches, it is easy to remember these branches of government. The judicial branch, on the other hand, “is expected to apply the law impartially without regard for politics or other consideration – being in this way independent – but also be responsible for the quality of their decision-making – being in this way accountable.”

This combination of independence from politics and accountability makes selecting judges a unique and important process. Every day, citizens fulfill their civic duty by reporting for jury duty or providing testimony. Based on our constitutional right “to a fair trial before a competent judge and a jury of one’s peers,” understanding how judges reach the bench, and how we can impact that decision, is just as important for ourselves and our fellow Americans as is choosing candidates for the executive and legislative branches.

For full coverage of the U.S. judicial system, see The Policy Circle’s Judicial Branch Brief.

Overview of the Courts

Trial courts and appellate courts make up the bulk of U.S. courts. In trial courts, either a judge or jury resolves factual disputes between the parties in deciding the case. Appellate courts, where the losing side goes if they’re unhappy with the result of the trial, do not decide factual disputes, but only determine whether the law was applied to those facts correctly by the trial judge. A panel of three judges usually makes decisions in appellate courts; there is no jury.

The U.S. has two very different judicial systems – the federal system and the state system. The federal system often gets the most attention because of the Supreme Court, but the state systems do much more work and are far larger. As described by former Justice Janice Rogers Brown, “the federal system is like a nice white and shiny pleasure yacht; the state system is much more like a super tanker.”

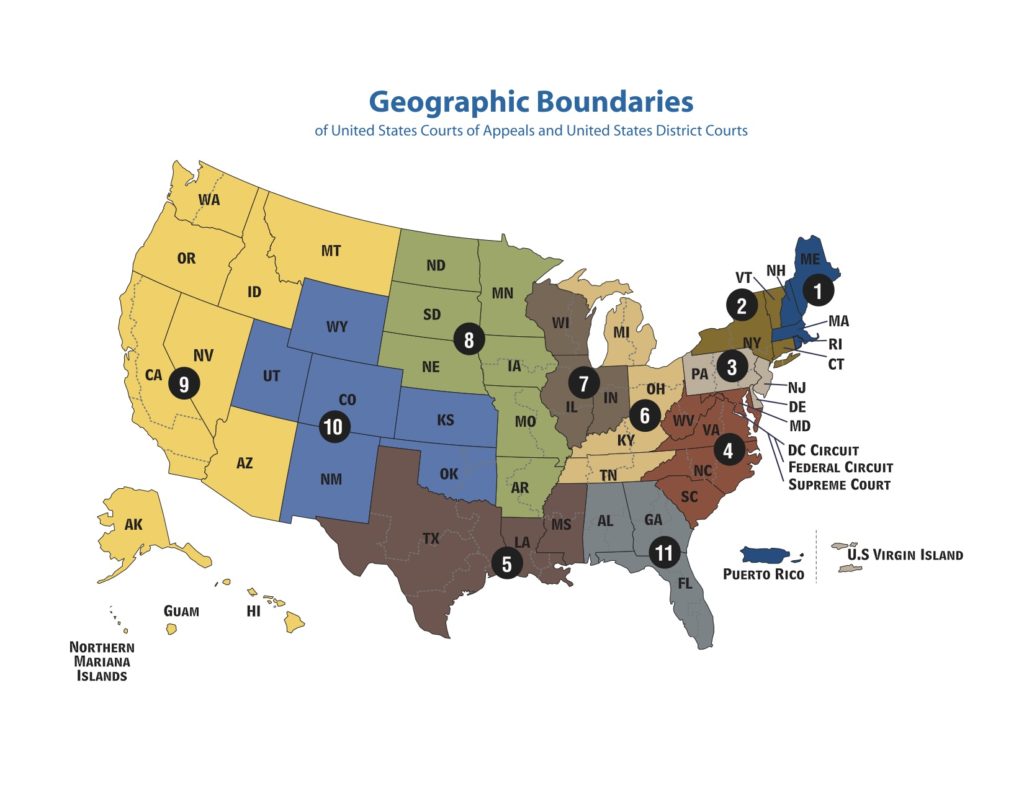

The entire federal court system consists of 94 district level trial courts that are organized into 12 regional circuits (11 regions and the D.C. circuit, see the map below). Each regional circuit and the Federal Circuit has its own court of appeals. There are also courts of appeals for the armed forces, for veterans, and international trade, and for patents, for a total of 16 intermediate appellate courts. The highest court of appeals, and the highest U.S. court, is the Supreme Court. See this breakdown of how the court system works, and how cases make their way to the Supreme Court (5 min):

Each state has its own court system with trial courts and appellate courts. Appellate courts include a “court of last resort,” usually called a supreme court. The exact makeup of these systems varies by state. For example, Texas and Oklahoma both have two courts of last resort, one for criminal cases and one for civil cases. Other states have “limited jurisdiction” trial courts, so there are different courts to hear cases revolving around different areas of law, as well as municipal and county courts on the local level. See your state’s courts and judges with Ballotpedia’s map.

In total, there are about 30,000 state judges and over 1,700 federal judges.

Judicial Selection at the Federal Level

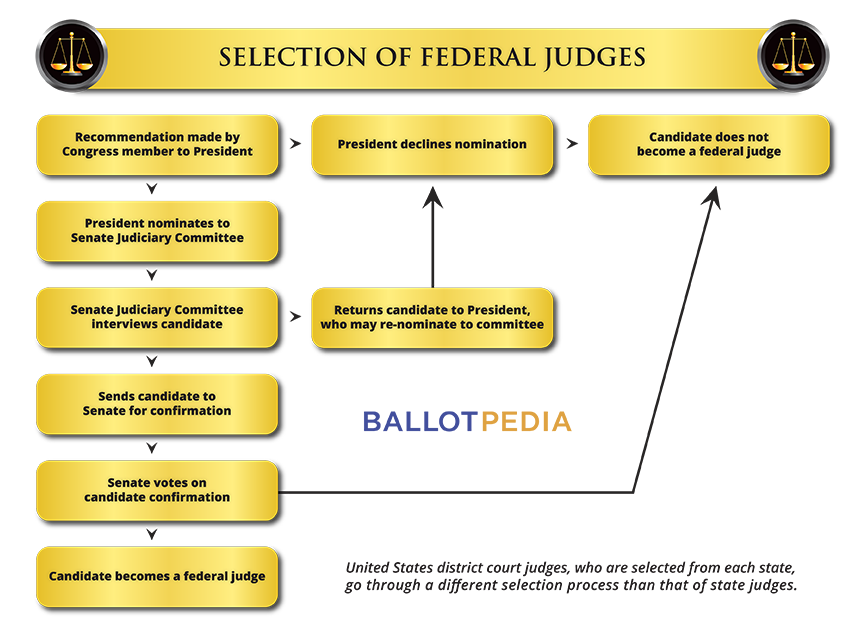

The U.S. Constitution says “the President ‘shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint’ judges” in the federal court system. This includes the federal trial courts, federal appellate courts, and the Supreme Court.

Qualifications

There are no standard qualifications for becoming a federal judge in terms of minimum age, years of experience, or specific legal training. However, a law degree is implicit; for example, while Supreme Court Justices are not required to be lawyers, every nominee has been. The demanding nature of the confirmation process, the complex and voluminous work following appointment, and the public’s expectations prompt Presidents to look for a “high degree of merit in their nominees.” Federal judges outside the district and appellate courts, such as bankruptcy judges, do have certain training requirements to ensure subject matter expertise.

Term Lengths

Most federal judges “enjoy life tenure,” although some including bankruptcy and magistrate judges have set term limits and may be reappointed. Federal judges may retire, but there is no mandatory retirement age. Many elect to take “senior status,” which permits a lighter work-load and creates a vacancy for the President to fill.

Selection

According to the University of Denver’s Institute for the Advancement of the American Legal System, “[a]lmost all judgeships on both the District Courts and Courts of Appeals are associated with particular states.” For this reason, home-state senators are usually very active when it comes to suggesting judicial nominees for vacancies in their states. Senators in 21 states use merit-based selection commissions to screen possible nominees and submit recommendations to the White House for federal judgeships in their states. Senators in other states also use similar screening committees. See if your state senators rely on commissions.

Members of the White House Staff and the Department of Justice often identify recommended potential nominees. These members review “an extensive and detailed questionnaire that each nominee must complete regarding his/her professional background and legal experience.” The FBI also runs private personal background checks and the American Bar Association’s Committee on the Federal Judiciary evaluates possible nominees’ professional qualifications. “Presidents are free to consult with, and receive advice from, whomever they choose,” so all of these reviews can factor into the President’s final decision when making nominations.

Article I, Section 5 of the Constitution “allows both houses of Congress to create their own rules for proceedings, including the judicial confirmation process. And under the Senate’s current standing rules, the nomination is sent to the Senate Judiciary Committee.” The Senate Judiciary Committee also investigates the candidates’ questionnaires and backgrounds. If both home-state senators signal support for the nominees from their state (submitted on blue pieces of paper known as “blue slips”) the Senate Judiciary Committee moves ahead by conducting public or private hearings, and then decides whether to recommend confirmation to the full Senate. The final step is for the full Senate to decide whether to approve the nominee, by majority vote.

Article I, Section 5 of the Constitution “allows both houses of Congress to create their own rules for proceedings, including the judicial confirmation process. And under the Senate’s current standing rules, the nomination is sent to the Senate Judiciary Committee.” The Senate Judiciary Committee also investigates the candidates’ questionnaires and backgrounds. If both home-state senators signal support for the nominees from their state (submitted on blue pieces of paper known as “blue slips”) the Senate Judiciary Committee moves ahead by conducting public or private hearings, and then decides whether to recommend confirmation to the full Senate. The final step is for the full Senate to decide whether to approve the nominee, by majority vote.

If approved by the Senate, the confirmed nominee receives an official document called a Commission, which allows them to assume the judicial office. They do so by taking the Oath of Office, typically administered by the Chief Judge of the Court, another judge on the Court, or one of the home-state senators. The new judge is sworn in during a ceremony called investiture.

To see all judgeship appointments by president since President Roosevelt, see this list from U.S. Courts.gov or The Heritage Foundation’s Judicial Appointments Tracker.

Scot Schraufnagel, Chair and Professor of Political Science at Northern Illinois University, explains this process and how it has changed in the last few decades (5 min):

Politicization

The Judicial branch is meant to be independent from the President and Congress, but “[p]olitical considerations typically play an important role in Supreme Court appointments.” According to Neal Devins of William & Mary Law School and Lawrence Baum of Ohio State University, since the 1990s “growing partisan polarization…has shaped the Court in multiple ways.” Even for federal trial and appellate courts, “[t]he Senate confirmation process too pays increasing attention to ideology, including party line votes that block the consideration of judicial nominees.”

This politicization has been seen clearly in the timing of court appointments. During presidential election years, “an ongoing subject of debate in the Senate has been how many U.S. circuit and district court nominations should be confirmed by year’s end, and how late in the year the Senate should continue to confirm them.” Some cite the “‘Thurmond Rule,’” which has been deemed more of an “informal Senate understanding” by which “the Senate, after a certain point in a presidential election year, would generally no longer act on judicial nominations, or act only on uncontroversial consensus nominees supported by the Senate leaders of both parties.”

This “informal theory” has also been dubbed “a phony excuse” to slow the nomination and confirmation process. “Regardless of the rhetoric on the issue,” reports the American Constitution Society, “there is virtually no precedent for a complete shutdown of judicial nominations upon the summer recess.” Based on average confirmation numbers during presidential election years since 1980, “a President could reasonably expect one circuit court confirmation and nine district court confirmations post-recess.”

This “informal theory” has also been dubbed “a phony excuse” to slow the nomination and confirmation process. “Regardless of the rhetoric on the issue,” reports the American Constitution Society, “there is virtually no precedent for a complete shutdown of judicial nominations upon the summer recess.” Based on average confirmation numbers during presidential election years since 1980, “a President could reasonably expect one circuit court confirmation and nine district court confirmations post-recess.”

It has been rarer for a Supreme Court nominee to be appointed before the election during a presidential election year. This occurrence came to mind as an issue in 2016 during the nomination of Justice Garland after the death of Justice Scalia, and again in 2020 during the nomination of Justice Barrett after the death of Justice Ginsburg. Besides these back-to-back cases, the opportunity to appoint a Supreme Court justice before an election or during an election has occurred infrequently. Since 1789, there have only been fourteen such vacancies on the Supreme Court, with the 14th resulting after the death of Justice Ginsburg.

For seven of the thirteen vacancies prior to 2020, nomination and confirmation were held during the election year. For these cases, there was an average of 227 days (7.5 months) between the vacancy occurring and the election date. The vacancy created by Justice Ginsburg occurred less than 50 days before the election.

In four other cases, the nominations were submitted but not confirmed during the election year. The most recent was the 2016 nomination of Justice Garland by President Obama. Prior to that, this had not occurred since 1852. In only two cases, nominations were not submitted until the following year. In 1861, this was because the initial nominee was rejected by the Senate. The other case was President Eisenhower’s recess appointment of Justice Brennan in October 1956; Brennan was then nominated and confirmed in March of 1957.

TED-Ed explores the politicization of the Supreme Court Nomination Process (4 min):

Evaluation

According to the Federal Judicial Center, a “judicial performance evaluation (JPE) program can serve to improve the administration of justice and enhance public confidence in the judiciary.” However, there are no official, nation-wide programs that evaluate federal judges’ performances. Some plans “have been implemented voluntarily by individual federal circuits, districts, or judges.”

Misconduct & Removal

The Judicial Conduct and Disability Act of 1980 allows any individual to file a complaint against a judge. Complaints are submitted to the chief judges of Courts of Appeals, who either dismiss the complaint if it is without merit, or appoint a committee of judges to investigate the complaint. The committee reports findings back to the circuit judicial council. Each circuit has a judicial council consisting of the chief circuit judge and an equal number of judges from District Courts and Courts of Appeals. If disciplinary action is necessary, it could be a reprimand or suspension, a request for resignation, or a recommendation to consider removing the judge from office.

Removing a federal judge from office can only happen by impeachment. Impeachable offenses are defined in the U.S. Constitution as “treason, bribery, and other ‘high crimes and misdemeanors’.” The House of Representatives impeaches, or charges, a sitting judge by majority vote. The case then moves to the Senate, which can convict and remove a judge by a two-thirds majority vote.

Removing a federal judge from office can only happen by impeachment. Impeachable offenses are defined in the U.S. Constitution as “treason, bribery, and other ‘high crimes and misdemeanors’.” The House of Representatives impeaches, or charges, a sitting judge by majority vote. The case then moves to the Senate, which can convict and remove a judge by a two-thirds majority vote.

Judicial Selection at the State Level

Just as each state has its own court system, methods for selecting judges vary from elections to appointments, and often depend on the type of court.

Qualifications

There are more specific qualifications to become a judge at the state level than there are at the federal level. Every judge in every state’s supreme court, intermediate appellate courts, and major trial courts is required to have a law degree. Other qualifications, such as age, years of legal experience, citizenship, or residence, are determined by each individual state. See what the qualifications are in your state.

Term Lengths

Term lengths for state judges vary by level of court and by state. Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island are the only states where judges serve life terms. In other states, judges have set term limits. Some state judge’s initial terms are shorter than a full term, usually 1-3 years. If reselected, subsequent terms range from 4 to 15 years. No states impose term limits on judges, but 32 states and the District of Columbia impose a mandatory retirement age.

Selection

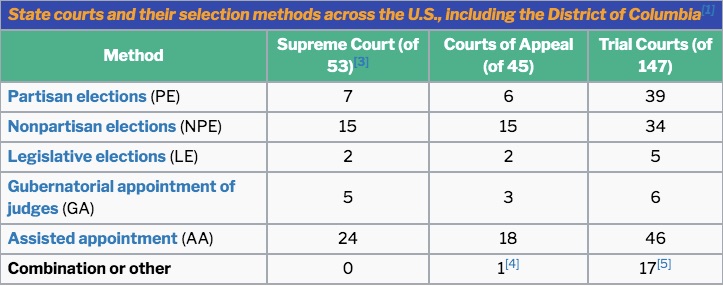

States employ five main methods for selecting judges: gubernatorial appointments, partisan elections, nonpartisan elections, legislative elections, and assisted appointments.

Gubernatorial Appointments

In states with gubernatorial appointments, the governor appoints judges, sometimes with approval required from the state legislature. Gubernatorial appointment with legislative confirmation was the judicial selection method in almost all states in the early 1800s. Today, three states use gubernatorial appointments, but governors are involved in some capacity across a majority of states.

Proponents argue that gubernatorial appointments protect the political independence of the judiciary by eliminating the need for political campaigns and the potential influence of special interest groups. Others maintain, however, that because judges are accountable to the residents of the state, county, or municipality they serve, residents should have a more direct voice in selecting judges.

Partisan Elections

In states with partisan elections, judges appear as candidates listed on a ballot, along with a political party affiliation, and are elected by voters. Mississippi became the first state to implement partisan judicial elections in 1832, followed by New York in 1846. By 1861, 24 of the 34 total states in the union were selecting judges in partisan elections. Today, judges are selected in partisan elections in seven states.

Some argue elections give community members more of a voice in holding judges accountable to community needs. The addition of a party affiliation can communicate to voters the potential judges’ values and ideologies. Others argue that elections open judges up to manipulation by special interest groups. They add that political affiliations can be confusing, as it can be unclear what partisanship looks like in every-day decision making in a courtroom.

Nonpartisan Elections

In states with nonpartisan elections, judges are elected by voters but their names are listed on ballots without a party affiliation. Illinois became the first state to adopt nonpartisan judicial elections in 1873, and by 1927 eleven more states had followed suit. In total, there are 15 states that select judges in nonpartisan elections (Illinois has since switched to partisan elections).

As with partisan elections, many argue that non-partisan elections provide community members a stronger voice in holding judges accountable. Some also believe that eliminating party affiliations eliminates the potential for divisive partisanship. Others maintain that party affiliation is important information for voters to know. Additionally, critics say that even if no party affiliation appears on the ballot, campaigns may become issue-based, which can still prompt involvement by special interest groups.

Legislative Elections

In states with legislative elections, the state legislature selects judges. Legislative elections were common in the early 1800s, but have largely been discontinued. Today, only South Carolina and Virginia use legislative elections to appoint judges.

Some argue that legislative elections, as opposed to gubernatorial appointments, prevent any one person or office from having too much influence over the judiciary. Others believe this method is not very different from or better than the gubernatorial system because it merely assigns the appointment power to another political entity that is often politically polarized.

Assisted Appointments

Also referred to as merit selection or the Missouri Plan, the assisted appointment method uses a nominating commission to review applications, call references, conduct interviews, and recommend to the governor candidates for appointment. Commission members are usually judges, attorneys, and laypersons, and are chosen by political officials, judges, or the state’s bar.

The governor then appoints a judge from the list, sometimes with additional confirmation from the legislature required. In most cases, after an initial term, the judge is up for a retention election, in which voters decide whether or not an incumbent judge should remain in office.

Albert Kales, co-founder of the American Judicature Society, first proposed the idea of “a nonpartisan, commission-selection process” for choosing judges in 1914. In 1940, Missouri became the first state to adopt the method after voters approved it. Today, assisted appointment is the most widely-used method, in 87 courts across 22 states and the District of Columbia.

Supporters of the assisted appointment method refer to it as merit selection, claiming input from the nominating commission results in more qualified judges. They also maintain that if judges do not need to run for election or re-election, it protects the judiciary from partisan politics. On the other hand, others argue that because many commission members are chosen by government officials, community members have little say in the matter, effectively rendering the appointment process no different than the gubernatorial or legislative appointment systems. Additionally, because nominating commissions’ meetings are not usually open to the public, there is little transparency.

The Federalist society breaks down these methods and their history (5 min):

Additional Factors

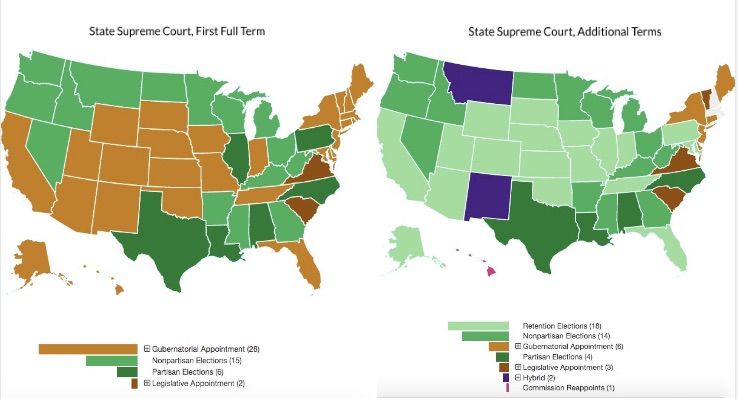

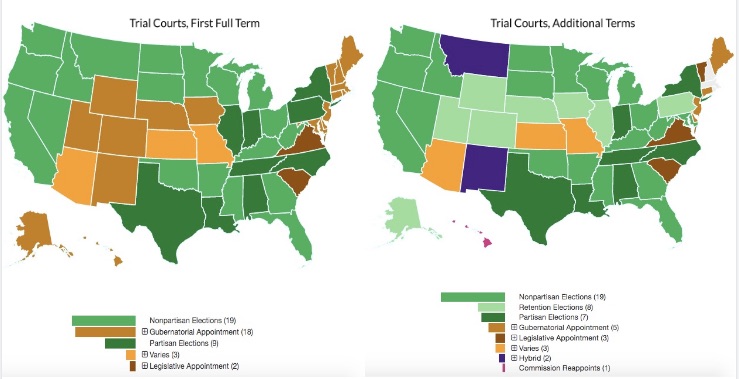

No state uses only one method for selecting judges; often they use a combination of systems depending on various considerations, including:

- The type of vacancy: For example, most interim vacancies (those that occur in the middle of a term) are not filled the same way as vacancy occurring at the end of a term.

- The type of court: For example, 26 states and the District of Columbia use gubernatorial appointments to fill initial high court terms, but only 20 states and the District of Columbia do so for trial courts. In Arizona, Kansas, and Missouri, judicial selection rules are localized at the district or county level.

- The term: For example, judges in Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and New Hampshire are appointed by the governor and serve for life or until they retire. In six other states, judges originally appointed by the governor need to be reappointed by the governor when their terms expire.

The following maps from the Brennan Center provide some insight into how methods for selecting judges can change:

Evaluations

As with methods for selecting judges, methods for evaluating judges also vary by state. Some states have official evaluation procedures led by independent commissions of judges, attorneys, and laypersons who have been selected by government officials, state bar association members, or the state judicial council. In other states, bar associations or civic organizations evaluate judges using public records such as written opinions and the judges’ sentencing patterns, or questionnaires completed by attorneys, jurors, litigants, witnesses, court staff members, and other judges. In states with elections, summaries of a judge’s evaluation are usually made available to the public. Even in states without elections, evaluations are often made available to promote public confidence in the judicial system. In other states, evaluations are shared only with the appointing elected official – usually the governor – or with the judge for self-improvement.

Misconduct & Removal

Every state has a judicial discipline commission to handle judicial misconduct cases. Similar to nominating commissions and independent evaluation commissions, these usually consist of judges, lawyers, and laypersons, appointed by other public officials or bar members. When someone files a complaint against a judge, this commission proceeds with a confidential investigation, determines if the judge acted in violation of the state’s particular code of judicial conduct, and decides what sanctions should be imposed, if necessary. As at the federal level, sanctions include reprimand, suspension, involuntary retirement, or removal from office.

States ordinarily employ one of three methods to remove a judge from office. Almost all states allow the state legislature to impeach and remove judges from office if it is proved that the judge committed offenses identified as impeachable by state law. Legislators have typically limited these to “serious ethical and criminal violations.” As a result, impeachment has rarely been used at the state level. Since the 1990s, only two state judges have been impeached, and only one was removed.

States also may remove judges even if they have not committed impeachable offenses. These cases are limited to situations where, for instance, the judge has overstepped his or her constitutional or legal authority as defined by state law. Ordinarily, it is impossible to remove judges simply because their rulings on the bench may upset a losing party.

Judges may also be removed through a “bill of address” in some states. The bill of address process allows the legislature (usually with consent from the governor) to vote for a judge to be removed from office. In eight states, voters are directly involved in the process through recall elections. Voters can gather signatures on a recall petition and present it to election officials, who set a date for a recall election, in which voters decide by a majority vote to remove the judge from office. Today, almost all states have a judicial discipline commission or board that investigates complaints against judges and makes recommendations to the state supreme court to suspend, retire, or remove a judge from office. See which methods your state uses to remove judges, from the National Center for State Courts.

Conclusion

The processes for selecting judges vary greatly, but are nonetheless important to understand at both the federal and state level court systems. The judiciary greatly affects our lives and civic duties. Knowing where powers lie at the federal level, and what our role as citizens is at the state level, is key to understanding the third branch of our government.

Additional Resources

- The Senate Committee on the Judiciary

- The American Bar Association’s Committee on the Federal Judiciary

- The Heritage Foundation: Judicial Appointments Tracker

Nominations & Vacancies

State Courts Information

- Justice Department: Judicial Districts

- National Center for State Courts: State Court Websites

- Court Statistics Project: Understanding State Courts

- Court Statistics Project: State Court Structure Charts

- Ballotpedia: Courts and Judges

Judicial Selection Methods

- Ballotpedia: Judicial Selection by State

- Ballotpedia: Judicial Elections Portal

- Federalist Society’s State Courts Guide: Judicial Selection by State

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Find out how your state and district approach judicial selection

- Do you know the judicial vacancies in your state or district?

- What are your state’s methods for filling judicial vacancies?

- What are your state’s qualifications for becoming a judge?

- Where are your state’s courts and administrative offices?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement personnel, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Who serve as judges in your state’s or district’s courts?

- What role does the governor play? Is there a commission?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, communications@thepolicycircle.org, for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policy makers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Explore your state’s court structure and who your state judges are with Ballotpedia’s Courts and Judges By State Map.

- Find out about federal district court judges in your state, as well as your state supreme court judges, appellate judges, trial court judges, and municipal judges.

- Determine whether your judges were appointed, and if so, by whom?

- See what, if any, judicial elections take place in your state with Ballotpedia’s Judicial Election Portal.

- Explore past judicial election results and see upcoming election information.

- Determine whether your judges were elected in partisan elections, and if so, to which party do they belong?

- See if there is room for your state or district to implement judicial evaluation plans, if it has not already.

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.