The United States political system was originally founded on the idea of consent of the governed. Today’s government relies on thousands of administrative officials, which makes it difficult for citizens to know who is making decisions. Only with transparency at the administrative level can citizens know the decision makers and the decision making process, which allows them to hold elected and appointed officials accountable for the results of those decisions.

Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

Watch The Policy Circle’s Move the Needle Virtual Experience: Transparency & Accountability, featuring Kristen Cox (former Executive Director of the Governor’s Office of Management & Budget for the State of Utah), Adam Andrzejewski (Founder & CEO of Open the Books), and Kirk Allen (Co-founder of Edgar County Watchdogs):

Case Study

The Paycheck Protection Program was meant to “help businesses keep their workforce employed during the COVID-19 crisis.” Intended recipients of the forgivable loans were members of the small business community that were hit hardest by the pandemic. When information on who was and was not receiving the loans was made public, there was massive public scrutiny. The program that would “dole out more than $800 billion dollars in forgivable loans” was actually “benefiting larger companies with access to capital at the expense of what one would consider to be a small business.”

National newspapers, watchdogs, and congressional oversight bodies all issued reports, which led to policy changes in legislation and executive policy. In December 2020, the COVID-19 relief bill “explicitly designated that a portion of the additional appropriations to the PPP be distributed by community financial institutions and mission-based lenders.” A little transparency was enough to hold the government accountable to the law as written, and hold Congress accountable to the stated objectives that the funds would go to the hardest hit communities to initiate change.

See businesses that received PPP loans in your community with this map, from Open the Books.

Why it Matters

America’s political system is based on the idea of consent of the governed, but there are thousands of administrative officials, and anywhere between 174 and 268 executive agencies, making and applying laws. This has created an opaque policy-making environment, the constitutionality of which has even been called into question. Without a degree of transparency it is impossible to know who is making the decisions, or who to hold accountable.

America’s political system is based on the idea of consent of the governed, but there are thousands of administrative officials, and anywhere between 174 and 268 executive agencies, making and applying laws. This has created an opaque policy-making environment, the constitutionality of which has even been called into question. Without a degree of transparency it is impossible to know who is making the decisions, or who to hold accountable.

American citizens are taught to participate in democracy through voting, ballot referendums, electing officials, and educating themselves on proposed legislation. Americans also must hold elected officials accountable for government waste and suboptimal decision making, and can only do so if we know what the government is doing.

Putting it in Context

A History of Government Transparency

The Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) gives the public the right to access government records that, even though not classified, are not otherwise available. It was originally proposed in 1955 after the Cold War, which resulted in a “rise in government secrecy.” The original legislation garnered support from newspapers and journalists, but not from the vast majority of Congressional representatives or federal agencies and officials. It eventually passed in 1966, but “lacked the teeth necessary to force government agencies to comply.”

Less than a decade later, in the wake of the 1974 Watergate scandal, the House and Senate introduced new requirements, such as faster timeframes for responses and sanctions for wrongly withheld information.

Over the next decades, FOIA was amended and altered numerous times. The 1976 Government in the Sunshine Act required government agencies to open meetings to the public. In 1982 a Reagan administration executive order “created new classification rules that made withholding potentially sensitive government information as a response to FOIA requests much easier. In 1996, the Electronic Freedom of Information Act Amendments required agencies to make documents available in electronic formats to be digitally distributed upon request.

In 2007, the Bush administration signed the OPEN Government Act, which extended services to news media and established the Office of Government Information Services to oversee government compliance with FOIA requests. In 2016, the Obama administration passed the FOIA Improvement Act, which required federal agencies to create a central online portal for anyone to file a request, and put a 25-year limit on federal agencies’ ability to withhold classified documents. Even with these changes, both administrations have been accused of being extremely secretive.

Does it Work?

Freedom of Information laws, also known as “sunshine laws,” exist at the federal, state, and local levels. These laws support the public’s right to access government records “from the meeting minutes of their local municipality to documents revealing the incorrect reporting of COVID-19 deaths occurring in New York nursing homes.”

Even so, “it remains common for government to resist transparency efforts, either by failing to provide the infrastructure necessary to process open records requests, or through a simple unwillingness to apply freedom of information laws in a manner consistent with their purposes,” explains Stephen Delie, director of labor policy and Workers for Opportunity at the Mackinac Center for Public Policy. FOIA requests are frequently met with delayed responses, require excessive fees, and end up with heavily redacted information.

Even so, “it remains common for government to resist transparency efforts, either by failing to provide the infrastructure necessary to process open records requests, or through a simple unwillingness to apply freedom of information laws in a manner consistent with their purposes,” explains Stephen Delie, director of labor policy and Workers for Opportunity at the Mackinac Center for Public Policy. FOIA requests are frequently met with delayed responses, require excessive fees, and end up with heavily redacted information.

FOIA authorizes nine exemptions. One, known as the (b)(3) exemption, authorizes withholding information under FOIA based on another federal statute that prohibits disclosure of the information. One report from the Government Accountability Office claims that between fiscal years 2010 and 2019, 91 federal agencies reported withholding information using at least one of the 256 (b)(3) exemptions more than 525,000 times.

Case Study: FOIA and Technology

The Federal Records Act (FRA) of 1950 “established the framework for records management programs in Federal Agencies,” and was amended by Congress in 2014 “to modernize the definition of a record and cover new forms of communication,” including email, messages, and instant messaging. Federal agencies’ records are important documents that can be accessed by the public through the FOIA. In the modern workplace, instant messaging is used to communicate and make decisions. Instant messages, texts, and emails can provide a trail exemplifying how decisions were made.

A 2018 investigation by Americans for Prosperity and Cause of Action found many agencies do not preserve instant messages in accordance with the updated 2014 policy. In fact, the investigation found some agencies failed to incorporate the amendments at all, not adhering to FRA guidance that “‘agencies must capture and manage these records in compliance with Federal records management laws, regulations, and policies.’”

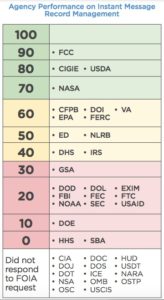

As part of the investigation, Americans for Prosperity and Cause of Action send FOIA requests to 39 agencies (a fraction of the total number of federal agencies). Of the 26 that responded:

- Three agencies have policies to automatically capture and preserve instant messages

- Council of Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency

- Department of Education

- Federal Communication Commission).

- Seven agencies direct employees to preserve messages manually as they deem necessary

- Department of Agriculture

- Department of Homeland Security

- Department of the Interior

- Environmental Protection Agency

- Internal Revenue Service

- Federal Energy Regulatory Commission

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration

The chart rates the 39 agencies contacted based on whether agencies’ policies are updated, whether they allow employees to use instant messaging, whether they preserve instant messages, and whether they produced messages upon the FOIA request.

All 50 states and DC have some form of FOIA law. See your state’s Freedom of Information Laws.

Government Watchdogs

Inspector General Act

The Inspector General Act of 1978 created “a system of overseers who work within – but independent of – federal agencies. The resulting offices are charged with detecting and preventing waste, fraud, and abuse, and with promoting economy, efficiency, and effectiveness in their respective agencies’ operations.” The act created the Council of Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency, an independent entity established within the executive branch.

There are 75 individual Federal Inspectors General, and six integrity-related officials from the Office of Management and Budget, the Office of Special Counsel, the Office of Government Ethics, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Office of Personnel Management. Find the Inspector General for federal agencies, and learn more about federal agencies in The Policy Circle’s Executive Branch Brief.

There are 75 individual Federal Inspectors General, and six integrity-related officials from the Office of Management and Budget, the Office of Special Counsel, the Office of Government Ethics, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and the Office of Personnel Management. Find the Inspector General for federal agencies, and learn more about federal agencies in The Policy Circle’s Executive Branch Brief.

Government Accountability Office

The Government Accountability Office, known as the GAO and referred to as the “congressional watchdog,” is an independent, nonpartisan agency that works for congress to examine how taxpayer dollars are spent. It racks federal spending, whether programs are meeting their goals, and if money has been spent wisely. GAO serves as an audit institution, issues legal decisions and opinions to federal agencies and Congress on the use of and accountability for public funds, and identifies fraud, waste, abuse, and mismanagement of federal funds.

See the GAO’s 2021 Annual Report for reducing fragmentation, overlap, and duplication in government programs.

Challenges and Areas for Reform

Wasteful Spending

Improper Payments

Improper payments are “payments made by the government to the wrong person, in the wrong amount, or for the wrong reason.” Improper payments can stem from an inability to access or verify data that could help determine whether recipients should receive payment, including death data or financial data. Mistakes inputting, classifying, or processing data can also lead to improper payments.

For example, in 2015, the Government Accountability Office found that federal agencies spent $55 billion of the $80 billion allocated for technology expenses on preserving older technology rather than updating it. Four years later, a November 2019 audit by the Office of the Inspector General revealed the Social Security Administration (SSA) in 2018 miscalculated the income of beneficiaries by nearly $1 billion and made $8 billion worth of improper payments. Part of the reason was outdated technology.

A report by Open the Books found that in 2019, the 20 largest federal agencies reported $175 billion improper payments, an average of $14.6 billion per month. Of that total, only $21 billion was recaptured. Medicaid, Medicare, and Earned Income Tax Credit payments accounted for $121 billion. Medicaid and Medicare improper payments rose from $64 billion in 2012 to $88 billion in 2017 to $103 billion in 2019; for the Earned Income Tax Credit program, 25% of payments from the IRS were improper in 2019. The Foundation for Government Accountability also found that “taxpayers could be on the hook for as much as $300 billion in improper unemployment payments” due to the expanded benefits in response to the coronavirus pandemic.

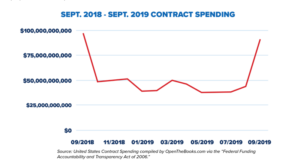

Besides improper payments, general waste is also a little known but large problem, particularly in year-end waste when the federal government goes on a “use-it-or-lose-it year-end spending spree” because agencies know that if they leave significant balances in their accounts at the end of the fiscal year, Congress may reduce their budget in the future (this is particular to discretionary spending, when funding comes from annual appropriations acts, as opposed to mandatory spending for things like Medicare and other entitlements). This spending spree has included spending on ammunition at non-military and non-law enforcement agencies, and for alcohol or food such as lobster and snow crab. See the chart below from Open the Books (the budget or fiscal year ends in September).

Taxpayers are the ones that suffer the consequences of improper payments. Little by little, the mismanagement of taxpayer money and wasteful government spending contributes more and more to the country’s debt. For more information on this topic and how it affects citizens, see The Policy Circle’s Federal Debt Brief.

Listen to Senator Lankford speak about wasteful government spending (6 min):

Earmarking

The Congressional Research Service defines earmarks as, “‘Provisions associated with legislation…that specify certain congressional spending priorities or in revenue bills that apply to a very limited number of individuals or entities.’” Legislators have “historically sought to insert earmarks to direct specific amounts of money to organizations or projects in the member’s home state or district.”

The Office of Management and Budget adds that earmarks are “funds provided by Congress for projects or programs where the congressional direction…circumvents Executive Branch merit-based or competitive allocation processes” and essentially “curtails the ability of the Executive Branch to manage critical aspects of the funds allocation process.”

In many cases, earmarks were a negotiating tool among legislators, but in the 2000s, “earmarking became synonymous with corruption,” plagued with high-profile scandals that prompted additional rules to prevent abuse. Congress then voted to ban earmarks entirely in 2011. In 2021, they were reintroduced in Congress.

Supporters say earmarks allow legislators to target funds for projects that can solve policy problems specific to the needs of their districts and constituents. Additionally, earmarks serve as “a vital incentive to encourage lawmakers to support broader legislation,” preventing gridlock and getting legislation passed. Critics argue whether it is actually “the purpose of Congress to fund the projects on the local wish list” if money is coming from nationwide taxpayers. An Open the Books analysis found in May 2021, 324 members of Congress proposed over 3,300 earmarks that amounted to $9.3 billion in taxpayer dollars. On average, earmarks tend to constitute less than one percent of discretionary spending.

John Hudak of Brookings Institution argues that the key to earmarks is transparency, adding that the ban in 2011 effectively transferred earmarks from Congress to the Executive Branch, and made the process more secretive. Hudak argues the return of earmarks should include safeguards for “expanding transparency regarding disclosing the member requesting earmarks and the recipients, identifying any connection the earmark has to the legislator or his/her family, capping the number of earmarks, and limiting the types of recipients who are eligible, among other requirements.” Further, it would be necessary to examine whether earmarking is making a difference in the districts and whether the safeguards are actually effective to maintain transparency and accountability among elected officials and how they spend taxpayer dollars.

Government Contracts

The government is not often thought of as a customer, but it buys many products and services. Federal, state, and local governments contract with businesses to fulfill these needs. “The process of requesting proposals, evaluating bids, and awarding contracts should take place on a level playing field. The government should consider a bid from any qualified business.” Still, fraud, uncompetitive bidding, and accessibility are issues that plague government contracts.

Favoritism

It was necessary that the government contract for medical supplies quickly during the coronavirus pandemic, but haste often leads to mistakes and cut corners. In July 2020, the GAO found that $9.4 billion in pandemic contracts had not been competitively awarded, meaning the government did not use the method to “ensure it gets the best value and the best price by soliciting proposals from several contractors.”

Some argue this was necessary due to the speed with which the country needed to act, but it also may indicate a level of favoritism. NPR reviewed a database of thousands of government contracts and found more than 250 companies received contracts worth more than $1 million without going through the competitive bidding process. Some had only registered to do business with the government that year, and some acted as middlemen, obtaining medical supplies from other manufacturers and even China. One contractor, whose company had been working as a federal contractor for a decade, “says connections in China enabled the company to deliver nearly 2 million masks in a matter of weeks, at a markup to the government of just 5%,” but others argue this defeats the purpose of supporting American companies.

Fraud

Fraud was another concern due to the speed with which contracts were awarded. A USA Today analysis found that through May 2020 the government awarded almost $500 million in pandemic response contracts to companies that had been accused of defrauding taxpayers. San Diego ventilator manufacturer ResMed settled a civil lawsuit alleging it had defrauded the government for $37 million in January 2020. Two months later in March 2020, the Department of Health and Human Services awarded the company $32 million for ventilators to fight COVID-19, without a competitive bidding process. As long as companies are not suspended or barred from doing business with the federal government, there is no federal law that prohibits this. Overall, vendors accused of defrauding the government received more than 6,100 total COVID-19 orders worth nearly $500 million through late May 2020, including $219 million without any type of competitive process. Many companies were sued based on the False Claims Act; some were advertising their products as made in America even though they allegedly came from China or India, and others said they were manufacturers when they were actually resellers and jacking up prices to the government. Other companies faced securities fraud, bribery, and negligence crimes.

This was a problem even before the coronavirus pandemic. Between 2013 and 2017, the Department of Defense “entered into more than 15 million contracts with contractors who had been indicted, fined, and/or convicted of fraud, or who reached settlement agreements.” The 15 million contracts were valued at $334 billion. A report covering 2001-2010 found the same pattern of criminal and civil offenders in defense contracting. For more, see Project On Government Oversight’s Federal Contractor Misconduct Database.

Accessibility

Even when speed is not a concern and government contracts are awarded after a competitive bidding process, there is still a question of how accessible contracts are for businesses, particularly small and minority-owned businesses. When the government searches for businesses to contract, it looks for the most efficient and cost-effective bidders, which are most often well-established, large-scale companies that can meet the government’s needs. To ensure large businesses don’t “muscle out” small businesses, the government has had a goal of 23% of contracts going to small businesses, a goal that it has hit for seven consecutive years from 2013-2019. In FY2019, the federal government spent $586 billion on contracts, $225.8 billion of which went to small businesses. The Congressional Research Service provides an overview of the Federal Procurement Process.

Reaching minority-owned businesses is more difficult; in 15 years, the government has never made its goal of spending 3% of contracts on businesses in economically depressed areas, and since 1996 has only hit the goal of 5% of contracts going to women-owned businesses in 2013 and 2019. According to Goldman Sachs 10,000 Small Businesses survey, there is a 15% gap between men and women business owners who received contracts from the federal government, and a 13% gap between those receiving contracts from state governments.

In 2016, a review of 100 business disparity studies by the U.S. Minority Business Development Agency (MBDA) found many of the individual studies focusing on individual cities from Atlanta to Minneapolis all showed “statistically significant and substantial underutilization of [women and minority-owned business enterprises] occurred in all procurement categories.” The MBDA reported in 2017 that “the needle has barely moved on boosting minority business participation in public contracts.” That year, $25.4 billion in federal contracts went to women-owned businesses. This record high was 5% of all federal contracts awarded; women own about 20% (1.1 million) of all employer businesses.

On the supply side, while government incentive programs exist, public officials are accused of hiring who they know, and programs have little oversight to make sure certain percentage of projects hire minority and women-owned businesses. On the demand side, many minority-owned businesses do not submit bids. The MBDA’s 2016 study surveyed businesses that did not submit contracts in Pittsburgh; over half said they did not have the right relationships or contacts, 49% said they had difficulty finding information, and almost a third said they perceived the process to be unfair. According to the Goldman Sachs 10,000 Small Business Voices program survey, about half of women owners who chose not to apply to federal contracts said it was because the process was too time consuming, 40% said it was too complicated, and 38% said they felt they weren’t likely to get a contract because small businesses weren’t prioritized.

Notions of government contracting being a closed network, or that information was sent too late or not at all, result in few bids from the roughly 1 million (18.3% of all business) minority-owned employer businesses in the U.S. Programs that foster more participation from minority-owned businesses have been central to reforms. The 8(a) Business Development program from the Small Business Association limits competition for certain contracts to “socially and economically disadvantaged small businesses” and offers business training, counseling, and marketing assistance. Similarly, the Small Business Administration has another program specific to women-owned businesses that has the goal of awarding 5% of federal contracting dollars to women-owned businesses. The program has only hit this goal twice (2015 and 2019) since the program’s 1996 implementation.

Small businesses tend to have the most impact on the local level in their communities, so local governments can play an important role; in fact, at the local level, women- and men-owned small businesses are equally likely to say they received a government contract. In Philadelphia, the local government offers assistance to smaller minority- and women-owned businesses so they have an opportunity to compete for contracts even with larger firms.

Economic Development Subsidies

Transparency and accountability in economic development incentives is a little known issue, mostly because details of economic development agreements between local governments and businesses are often not publicly available. In some states, recipients of economic development dollars are given a say in what details are released to the public; in others, there are statutes that favor privacy regarding tax break packages, loans, and grants. Some claim the secrecy is necessary to maintain competitiveness.

Although publicly-traded companies must disclose their sales, stock transactions, and sources of revenue, “in many cases of economic development packages handed out by governments, the public is shut out.” Even public records laws have provisions that protect trade secrets; the FOIA trade secrets exemption is “widely used and liberally interpreted,” resulting in little to no public disclosure, despite the fact that these subsidies are funded by taxpayer money. Estimates say state and local governments award anywhere between $40 and $70 billion annually (with some estimates as high as $90 billion) in subsidies to attract and retain businesses. The Policy Circle’s Government, Community, and Sports Teams: Tax Credits brief dives deeper into these subsidies.

Since 2003, the Texas Enterprise Fund (TEF) has used tax breaks (funded by taxpayer money) to attract companies in exchange for the promise of jobs. In 2015, the Texas Supreme Court ruled that “economic development groups are no longer subject to the state’s public records law despite being funded in part by cities and counties,” which prompted economic development councils across the state to remove data from their online portals.

In 2017, A professor and Ph.D. candidate at the University of Texas examining economic development ventures in Texas focused on the TEF and filed public records requests with 164 recipients. There were 45 companies that challenged the record requests. Of the successfully obtained records, more than 25% were granted changes to contracts due to a failure to comply with the initial requirements. Overall, the study found “companies that receive millions of dollars in incentives to locate to Texas frequently renegotiate their contracts, often in secret, to get better deals at taxpayers expense.”

In June 2021, the Texas Legislature did not renew the Texas Economic Development Act, due to “doubts about the number of businesses that actually needed the incentives to come, among other flaws.” It also passed a bill requiring the creation of a database of local economic development agreements, although the Texas Public Policy Foundation maintains access to economic development negotiations is still restricted. Under two acts, “economic development negotiations are excluded from the open government statutes, resulting in taxpayers being effectively shut out of what government units negotiate and offer select businesses with taxpayer money only to be too often presented with a done deal.” This creates an incentive race, with the government offering increasingly higher subsidies and businesses asking for increasingly higher incentives, which does not benefit taxpayers and businesses that are not subsidized.

Texas is not alone; Free to Choose also explored corporate welfare, tax exemptions, and subsidies in Louisiana, Tennessee, and elsewhere in an upcoming documentary, Corporate Welfare, Where’s The Outrage? See the trailer (2 min):

Conclusion

Transparency is necessary for accountability. Even with government statutes, it can still be a challenge for the public to access information that would help them determine whether their elected and appointed officials are ensuring taxpayer dollars are spent wisely. Citizens do not only engage with their government by voting; it is also necessary for them to know what is going on in their communities so they can ensure whoever they voted for is making good on their promises, and if they are not, to hold them accountable.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Investigate the budget and spending of your municipality or state and district on a specific initiative such as economic development, workforce development, or a local project such as infrastructure maintenance/construction.

- What are your state’s transparency laws in regards to freedom of information?

- Find out what agency is responsible for the initiative that you are looking into, such as the Department of Labor, or Community Affairs.

- Look on the website for information about:

- Budget

- Salaries

- Procurement Process

- Current special projects

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community, in particular on the initiative that you are interested in? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, government agency leaders, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Make a list with contact information for the groups, committees, and departments involved.

- What steps have your state’s or community’s elected and appointed officials taken to enhance transparency and accountability?

- How do you hold elected officials accountable in your community or state?

- Is there a coalition, task force, or watchdog agency, or does one need to be formed?

- Does your state have a transparency center or department?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Reach out to talk to the people responsible for the initiative and the process. You have the right to know how dollars are spent, what the measures of success are, which contractors have been hired, and how the selection process works.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with community organizations, school boards, and local businesses.

Plan: Determine your goal and set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar or your local community meetings (public consultations, town halls, surveys, etc.)

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, communications@thepolicycircle.org, for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policy makers, and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Investigate public employee salaries and pensions in your state or municipality.

- See this tutorial from Open The Books, or use their Mapping Tool.

- Explore OpenPayrolls or FederalPay

- Determine how your state ranks in terms of salary payments and overall spending.

- See if there are local watchdog groups in your state or municipality, such as Edgar County Watchdogs.

- Visit FederalPay to look up data related to the Paycheck Protection Program.

- See how your state ranks in terms of economic development subsidies.

- Explore Citizens Against Government Waste’s Congressional Pig Book and Earmark Database to see how your state is being affected.

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.

Additional Resources

- Women Impacting Public Policy

- The Center for Public Integrity

- Project on Government Oversight

- Electronic Privacy Information Center – Open Government

- The Federalist Society’s Regulatory Transparency Project

- Cause of Action Institute

- Open The Books

- Citizens Against Government Waste: Congressional Pig Book

- Minority Business Development Agency