Introduction

View The Executive Summary For This Brief

“Who do you think of when I say the word ‘veteran’?” starts Sara Maniscalco Robinson in a July 2022 Ted Talk. “Is it the little old man in the grocery store wearing a black cap that says ‘World War II veteran’ on it? Perhaps in your mind’s eyes it’s the gentleman at the end of the bar covered in tattoos and drowning himself in alcohol for his post-traumatic stress? Maybe you’re imagining a man on a street corner holding up a cardboard sign that says: ‘Homeless Vet. Every little bit helps. God bless America.’ The one person I bet you did not imagine, was me.”

As the president, founder and CEO of the Iowa Veterans’ Perspective, Robinson has interviewed hundreds of veterans to go beyond stereotypes about veterans and into the common theme of service that ties them together. The work of veterans and of those who provide services for them affect the families they come home to, the employers they work for, and the societies they make their homes in. What is life like for veterans as they transition from active-duty service? With a greater understanding comes deeper appreciation for the issues and challenges faced by military personnel and their families, veterans, and the agencies that support them.

Why It Matters

Annually, close to 200,000 active-duty service members leave the military and join the veteran community. They become students, employees, and entrepreneurs. At the same time, their military background presents unique challenges for these individuals as they transition to civilian life.

By the Numbers

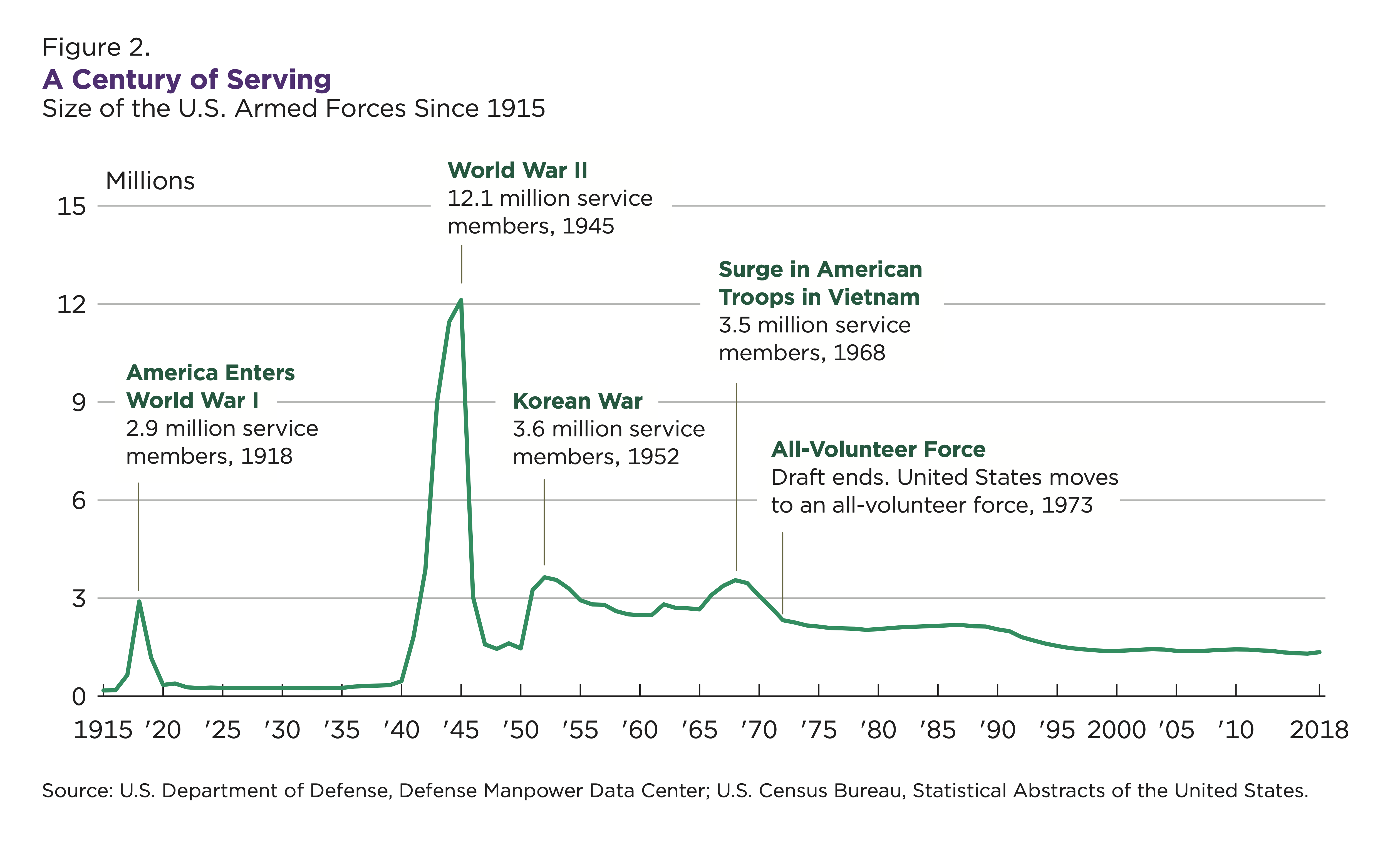

An estimated 18 million Americans (about 7% of the population) are veterans of the U.S military. Between 2000 and 2018, the veteran population declined by a third, from 26.4 million to 18 million. The armed forces today are significantly smaller today than they were in the past, partially due to today’s all-volunteer system and because of the aging of veterans. The median age of U.S. veterans is 65.

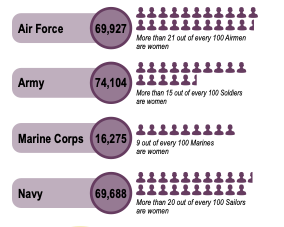

Women were first formally included in the military with the Army Nurse Corps. Women began flying combat missions and serving on Navy combat ships in the 1990s. The ban on women in combat was lifted in 2015. From 1980 to 2018, the proportion of female veterans increased from 4% to 9%. Only 4% of Vietnam-era veterans were women, compared with 17% of all post-9/11 veterans.

In 2018, 25% of all veterans had “an injury, disease, or disability that active duty either caused or aggravated,” with post-9/11 veterans suffering the majority of disabilities. In a 2021 study from the Bush Center, 53% of post-9/11 veterans reported physical health conditions, with chronic pain (41%) and sleep problems (31%) the most cited.

The Role of Government

Federal

Federal

Today, a pair of metal plaques bearing the words, “To care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow, and his orphan,” can be found at the entrance of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Headquarters in Washington, D.C. From President Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural address in March of 1865, the statement “affirmed the government’s obligation to care for those injured during war and to provide for the families of those who perished on the battlefield.”

Executive Branch

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) provides the following key benefits and services to veterans:

- Health care services through the Veterans Health Administration, the largest integrated healthcare network in the United States, which includes over 1,200 facilities and serves 9 million enrolled veterans every year;

- Benefits through the Veterans Benefits Administration, which helps service members transition out of the military and assists with education, home loans, life insurance, and other areas;

- Burial services through the National Cemetery Administration, which maintains more than 150 cemeteries; and

- Emergency management services to ensure the nation is prepared to respond to war, terrorism, national emergencies, and natural disaster “by developing plans and taking actions to ensure continued service to veterans, as well as to support national, state, and local emergency management, public health, safety and homeland security efforts.”

The budget for fiscal year 2022 (Oct-Sept) for the VA amounted to $270 billion. For FY2023, the president’s budget requested $301.4 billion.

The budget for fiscal year 2022 (Oct-Sept) for the VA amounted to $270 billion. For FY2023, the president’s budget requested $301.4 billion.

The funding allows the VA to do the following:

- Oversee the largest integrated health care system in the United States, supporting over 9.2 million enrolled veterans;

- Provide disability compensation for over 6 million veterans and their survivors;

- Administer pension benefits for nearly 277,000 veterans and their survivors;

- Oversee a home mortgage program with a portfolio of 4.1 million active loans; and

- Provide education-assistance programs and veteran-employment benefits.

Congress

The Senate and House Committees on Veterans’ Affairs have jurisdiction over the following:

- Veterans’ hospitals, medical care, and treatment;

- Veterans’ compensation, education, vocational rehabilitation, and the readjustment of service members to civilian life;

- Veterans’ pensions and life insurance; and

- The Department of Veterans Affairs, including the Veterans Benefits Administration and the Veterans Health Administration

State

The National Association of State Directors of Veterans Affairs (NASDVA) formed after World War II to help veterans integrate the federal entitlements available to them with state-specific benefits. NASDVA also maintains a compilation of state-specific veterans associations. Made up of state directors and commissioners of Veterans Affairs, NASDVA is the country’s second-largest service provider to veterans. Additional lists of state-specific resources can be found through the State Departments of Veterans Affairs.

Local

The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) also maintains a site for local service providers, which provide the following services:

- VA health;

- Urgent care;

- Emergency care;

- VA-network community providers;

- VA-network pharmacies;

- VA benefits;

- VA cemeteries; and

- Vet centers.

Private Sector

Health care is a key area in which the private sector is involved. For the most part, the VA provides health care for veterans, but some individuals may turn to private health-care providers. In the Bush Center’s 2021 survey on Advancing Veteran Employment, Education & Health and Well-being, fewer than half of respondents agreed that doctors and providers in private practice understand the military culture or challenges facing post-9/11 veterans and service members. This has led to a rise in specialized care options designed for veterans, including the Warrior Care Network, the Veteran Wellness Alliance, the Cohen Veterans Network, and the SHARE Military Initiative at Shepherd Center.

Additionally, there are over 45,000 philanthropic organizations that self-identify as veteran-serving organizations, such as SoldierStrong, a public charity that provides technology, advancements and educational opportunities to veterans. AmericaServes is a national coordinated network of organizations dedicated to serving the military community. Academic institutions are another resource for veterans, and often partner with these organizations; one example is Syracuse University’s Institute for Veterans and Military Families. See this directory of veterans service organizations.

Challenges & Areas For Reform

Education

Through the 1944 Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, also known as the GI Bill, the government supports academic pursuits for veterans by providing them with funds for college education and job training. In the private sector, SoldierStrong’s SoldierScholarship Program fills any tuition gaps government benefits do not cover for specific programs, such as those at Georgetown University and Syracuse University. The Warrior-Scholar Project offers “academic boot camps” to help veterans prepare to attend college. While on campus, Student Veterans of America offers resources, support, training, and networking opportunities through on-campus chapters.

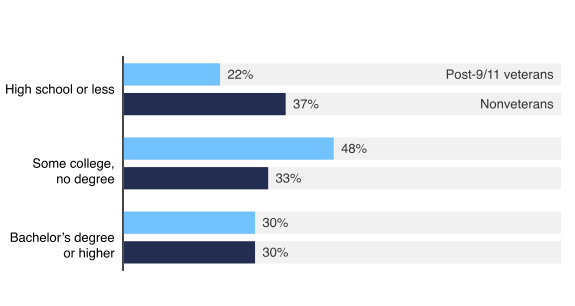

According to a report from the Rand Corporation, while many service members retire after 20 or more years of service, a typical enlisted service member retires around the age of 23 and without a four-year college degree. According to the Rand report, education benefits are necessary for veterans to maintain or improve their positions in society, increase access to careers not open to those without post-secondary education and to gain skills that transfer more easily to the civilian workforce. Data from the Census Bureau indicate that post-9/11 veterans are more likely to be employed, have health insurance, and be enrolled in school than their non-veteran counterparts because of education benefits. Education benefits can also help military spouses’ careers, which can suffer from frequent moves and other service-related demands.

These benefits also encourage young people to enlist. According to the National Commission on Military, National, and Public Service, “high school students increasingly view military service as incompatible with postsecondary education and often choose to attend college or vocational school in lieu of joining the military, even when they are interested in serving.” Benefits, as well as increased opportunities for youths to explore military service opportunities – such as Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC), which allows individuals to simultaneously attend college and train to be an Army officer, can strengthen recruiting.

Employment

About 80% of post-9/11 veterans participate in the civilian labor force, a statistic that has held steady since 2013. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the unemployment rate of veterans in 2021 (4.4%) was lower than the rate for nonveterans (5.3%). In May 2022, the veteran unemployment rate was 2.9%, compared with 3.6% for non-veterans.

Over one in ten veterans end up working in elected office. According to data following the 2020 election from the National Conference of State Legislatures, there were at least 911 military veterans serving in state legislatures, making up 12.3% of the total 7,383 state legislators nationwide. In addition, there are 91 veterans in Congress: 17 in the Senate and 74 in the House of Representatives.

Helping veterans translate their skills to civilian employers is an area of focus for many veteran-serving organizations. The Bush Center’s Military Service Initiative aims to help post-9/11 veterans and their families transition successfully to civilian life. With support from Syracuse University’s Institute for Veterans and Military Families, it offers career training and community employment services. The government also offers a number of programs for veteran employment, from federal apprenticeships for veterans to training services from the Department of Labor.

Some veterans choose to go a step further and start their own businesses. Nearly 25% of veterans express interest in starting their own businesses. According to the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA), veterans own about 380,000 employer businesses (6.8%), employing 4.2 million workers. Famous veteran entrepreneurs include the founders of Nike, FedEx, GoDaddy, Enterprise Rent-A-Car, and Esurance.

Boots to Business is an entrepreneurial program offered on military installations worldwide as part of the DoD’s Transition Assistance Program helping veterans transition to civilian life. It also includes programs specific to women veterans, service-disabled veterans, and military spouses. Other programs include VETRn, which trains veteran small-business owners and their families on growing their businesses and VetFran, which assists veterans in franchise businesses; Additionally, the Office of Veterans Business Development under the SBA provides access to capital and entrepreneurship preparation for veterans, service-disabled veterans, active duty service members, reservists, service members transitioning to civilian life, and dependents and survivors of service members. Veteran Business Outreach Centers, also under the SBA, provide training, counseling, referrals and workshops.

Financial Stress

Many members of the armed services joined after high school, or soon after graduating college. These individuals come of age in the military, and it is not until they return to civilian life that they need to learn how to manage bills and budgeting that had not been a consideration while serving.

In the Bush Center’s 2021 survey on Advancing Veteran Employment, Education & Health and Well-being, 35% of post-9/11 veterans reported trouble paying bills the first few years after leaving the military. According to the 2021 Military Family Lifestyle Survey, 53% of all post-9/11 veteran respondents indicated they were experiencing financial stress, with 30% citing excessive credit-card debt and 24% citing unemployment and underemployment.

The effects of financial stress can be wide-ranging and long-lasting. A 2013 study of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans in the American Journal of Public Health found “a consistent correlation between money mismanagement and homelessness overall…regardless of income level, demographics, or clinical factors such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or traumatic brain injury (TBI).” In fact, in terms of predicting future homelessness among veterans, financial management proved to be just as important as income. In 2020, there were over 37,000 identified homeless veterans in the United States, accounting for 8% of all homeless adults, according to a 2021 HUD report. For 2021, there were approximately 20,000 sheltered homeless vets. (The totals of unsheltered veterans were not included in 2021 on account of COVID-19 data difficulties.)

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau offers resources specifically for military families and veterans who can be targeted by scams. In 2016, the Department of Defense established an Office of Financial Readiness. Each military department has since implemented programs to “provide members of the armed forces comprehensive financial literacy training.” Also in the private sector are organizations such as the Wounded Warrior Project, which has a financial-education program. Syracuse University’s Institute for Veterans & Military Families was co-founded with JP Morgan Chase and has financial resources and programs for the military-connected community. See more in The Policy Circle’s Financial Literacy Brief.

Mental Health

Depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are the most publicized mental-health challenges facing military veterans; an estimated 14-16% of service members deployed to Afghanistan and Iraq have PTSD or depression. Other issues equally harmful and prevalent include suicide, traumatic brain injury, substance abuse, and interpersonal violence.

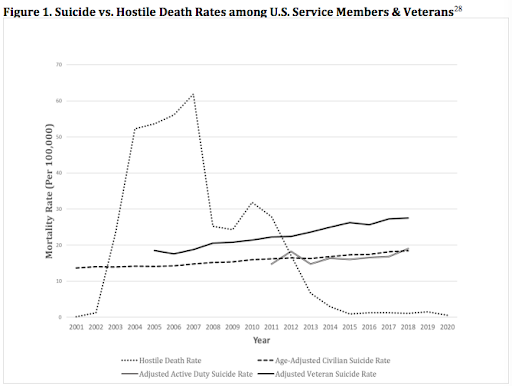

According to Brown University’s Cost of War, since 2012, suicide rates for active-duty service members and veterans (30,000+) have outpaced those of combat-related deaths in post-9/11 conflicts (just over 7,000). The DoD reports that the suicide rate for veterans is 1.5 times that of the general population, although this is likely an undercount because DoD data do not include reserve numbers or members of the National Guard. A 2021 report from the VA puts the rate at closer to 1.8 times that of the general population.

The Brown study cites a few reasons to explain the rise in mental health concerns:

- The nature of warfare, from exposure to combat to the protracted length of war;

- Military culture, from rigorous training and schedules to the dominant masculine identity that makes asking for help during trauma difficult and maintains the idea that acknowledging mental illness may be viewed as a sign of weakness.

In the Bush Center’s 2021 survey on Advancing Veteran Employment, Education & Health and Well-being, 83% of those reporting physical health problems in the past 12 months received treatments, compared with 42% of those who reported experiencing mental-health problems. Among post-9/11 veterans, “My mental health problem would go on my record” and “I would be seen as weak” were the most frequently cited reasons for not seeking help.

Congress provides $20 million annually to the DoD for suicide prevention programs and research, and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) receives billions of dollars to combat suicide annually. In fiscal year 2021 (Oct-Sept) $10.2 billion was dedicated to veteran suicide prevention. The DoD also began Resilience Training in 2008. According to the Brown study, the training has reported reductions in self blame and increased positive coping skills among service members. Additionally, the Army shortened deployment length and increased dwell time (time between deployments) at members’ home bases in 2011, based on evidence that longer dwell time is associated with a lower risk of PTSD.

One dilemma with shorter deployments and increased dwell times has been the shrinking numbers of active-duty service members, compared with other periods in history. The U.S. military has been voluntary since 1973, which comparatively has resulted in fewer total service members. Army Chief of Staff General James McConville says that while he prefers rotations every four years for service members, in actuality rotations are closer to 1-3 years. In sum, shrinking forces will only add extra strain to existing troops, creating a recipe for burnout.

One public-private partnership seeking to address this is SoldierStrong’s BraveMind initiative. In partnership with the University of Southern California Institute for Creative Technologies and the VA Innovation Center, BraveMind offers a virtual reality therapy program for veterans experiencing post-traumatic stress. For more unique and successful programs dedicated to helping veterans, see The Policy Circle’s Mental Health Brief.

Sherman Gillums, Jr., Chief Strategy Officer at the National Alliance on Mental Illness and a U.S. Marine for 12 years, discusses veteran mental health (10 min).

Homelessness

Between 2010 and 2022, the rate of homelessness among veterans has decreased. However, in 2020, there were still over 37,000 identified homeless veterans in the United States, accounting for 8% of all homeless adults, according to a 2021 HUD report. In an effort to reduce homelessness among veterans, the Department of Veterans Homeless Service Office provides the following programs:

- Housing programs following the premise of Housing First, which does not require veterans to undergo sobriety tests, along with additional programs for housing, such as assistance for families and rental vouchers;

- Employment services targeted to homeless veterans or those at risk of homelessness;

- Health care services, focusing on mental illness and substance abuse, alongside “medical homes” with a nurse and social worker tailored to the specific needs of the veterans;

- Veterans justice programs, including outreach in prisons and help with reentry following incarceration;

- An Office of community engagement, which serves as a hub for public and private partnerships; and

- Interagency programs and services, such as the Veterans Benefits Administration Outreach program to provide resources to veterans at risk of homelessness.

Within the veteran population, the rates of homelessness varied across different geographic regions and demographics in the following ways:

- Men accounted for 92% of sheltered homeless veterans in 2021 but female veterans experiencing homelessness were more likely than men to have a child under the age of 18 in their households;

- Black veterans accounted for a third of the sheltered homeless veteran population even though 12% of veterans are Black;

- Over a third of veterans experiencing sheltered homelessness lived in California, Florida, New York or Texas;

- The states with the lowest rates of sheltered homelessness were Mississippi, Wyoming, Arkansas and Georgia.

The Department of Veterans Affairs

According to a 2021 report by the Government Accountability Office (GAO), the VA has spent 6 years on the GAO’s High-Risk List and “still lacks a clear and comprehensive roadmap to address VA health care concerns and has not demonstrated meaningful progress.” The VA was added to the High-Risk List in 2015 based on the following issues:

- Ambiguous policies and inconsistent processes;

- Inadequate oversight and accountability;

- Information-technology challenges;

- Inadequate training for VA staff;

- Unclear resource needs and allocation priorities.

Accessing VA care centers can be difficult for many veterans, especially those in rural areas, but this is also the case among private providers. Across all health-care providers, there are worker shortages, a lack of available appointments, a lack of awareness about the specific issues facing veterans and poor training in evidence-based treatments. In the Bush Center’s 2021 survey on Advancing Veteran Employment, Education & Health and Well-being, fewer than half of survey respondents agreed that private providers understand military culture and health challenges facing post-9/11 vets and service members. Among the survey respondents, 72% said they had trust in the VA, up from 60% in 2016.

Conclusion

Over 200,000 Americans transition from active-duty service members to veterans each year, affecting not only the veterans themselves but also the families and cities they return to. While the backgrounds of veterans vary, they are all tied together by their work in serving the U.S. military and many of them face unique issues, ranging from health concerns related to their deployments to finding the best path to new careers in the civilian workforce. Several institutions, from the federal Department of Veterans Affairs to state, local and private organizations work to support veterans. Understanding the ways these departments and institutions work together helps inform our society of their successes, such as through outreach to financially vulnerable veteran communities, and shortcomings, such as through difficulties for some in accessing VA care. As a result, we can work toward more tailored policies and effective strategies for the next generation of veterans in the country.

Ways To Get Involved & What You Can Do

Measure: Find out about the presence of the veterans in your state and district.

- Is there a VA location nearby?

- Do you know how large the population of veterans is in your community?

- Is there a coalition or task force dedicated to serving veterans in your community, such as one addressing homelessness or mental health?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Are there any veteran-serving organizations operating in your community?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with law enforcement, first responders, faith-based organizations, local hospitals, community organizations, school boards, and local businesses.

Plan: Set some milestones with others to maximize your impact based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, communications@thepolicycircle.org, for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policy makers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Consider volunteering with an organization that benefits service members, their families, or veterans in your community.

- Talk to local business owners or reach out to your local chamber of commerce to find out about veteran employment in your neighborhood.

- Acknowledge veteran families in the businesses that you are part of.

- Reach out to veterans and ask about their experiences.

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.