Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

Case Study

When we calculate our taxes, we usually consider taxes in terms of how much money we will need to pay. But this thinking doesn’t include all the indirect costs that taxes impose, such as the number of hours Americans spend recordkeeping, learning about the law, filling out the required forms and schedules, and submitting information to the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). According to research from the American Action Forum (AAF), filing taxes requires 8 billion hours of paperwork. This is the equivalent of 25 hours per person, or 54 hours per taxpayer, meaning the average working American spends about a week preparing taxes.

The IRS estimates the cost of filing taxes to be $86 billion annually, although this cost only factors in the individual income tax and business income tax. AAF estimates the number is closer to $170 billion for other tax returns.

How much time or money have you spent to fill out your tax return?

Why it Matters

If you’ve ever taken a close look at your paycheck, you’ve seen how much is deducted in taxes. And if you’ve ever taken on the mammoth task of filing your own taxes, you know there is nothing simple about the process. There are taxes on the money we make, the items we buy, and the property we own, and then there are different taxes and tax rates for individuals and businesses. How Americans think about taxes needs to be put in context and connected to what taxes pay for at both the state and national level – anything and everything from highway construction to Social Security – and what their effects are in terms of government debts and deficits.

Putting it in Context

History

Taxes have played a significant role in U.S. history, dating back to the country’s inception. “Taxation without representation” was a primary driver of the original thirteen colonies’ desire to gain independence from England. Grover Norquist, president of Americans for Tax Reform, writes in Foreign Policy, “Taxation in the colonies consisted of property taxes, poll taxes on men over 18, excise taxes, and forced labor contributions of a few days a month to build roads and assume other ‘public functions’ such as constable, assessor, or ‘hog reeve’ (an officer charged with the prevention or appraising of damages by stray swine,’ according to the Oxford English Dictionary).” Subsequent British taxes levied on the American colonies, such as the Stamp Act of 1765 and the Tea Act of 1773, fueled the colonists’ revolt against England.

Taxes have played a significant role in U.S. history, dating back to the country’s inception. “Taxation without representation” was a primary driver of the original thirteen colonies’ desire to gain independence from England. Grover Norquist, president of Americans for Tax Reform, writes in Foreign Policy, “Taxation in the colonies consisted of property taxes, poll taxes on men over 18, excise taxes, and forced labor contributions of a few days a month to build roads and assume other ‘public functions’ such as constable, assessor, or ‘hog reeve’ (an officer charged with the prevention or appraising of damages by stray swine,’ according to the Oxford English Dictionary).” Subsequent British taxes levied on the American colonies, such as the Stamp Act of 1765 and the Tea Act of 1773, fueled the colonists’ revolt against England.

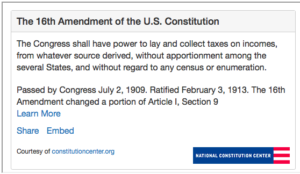

Federal income tax in the United States was first enacted in 1913, after the 16th Amendment was ratified, “making it possible to enact a modern, nationwide income tax.”

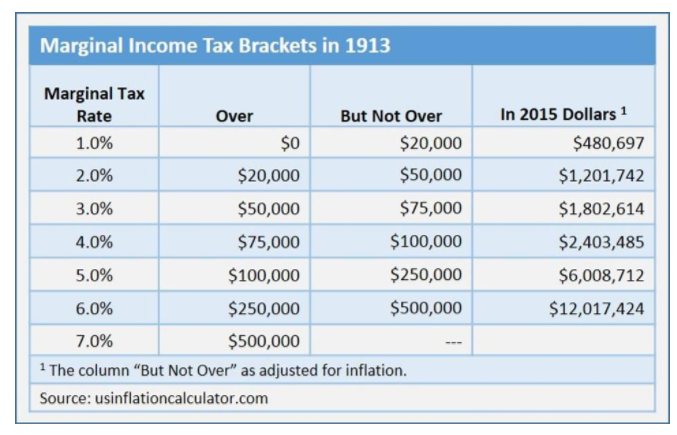

After ratifying the 16th Amendment, Congress passed the Underwood-Tariff Act, also called the Revenue Act of 1913, which levied “a graduated income tax on U.S. residents.” The chart below, from the Forbes article, “A Brief History of the Individual and Corporate Income Tax,” contains the marginal tax brackets in place in 1913 and what the approximate equivalent amount would have been in 2015. It illustrates how “the new income tax applied primarily to higher wage earners… For example, an individual earning $20,000 in 1913 would have been in the 1.0% marginal bracket. $20,000 in 1913 is equivalent to $480,697 [in 2015] (based on an average annual rate of inflation of 3.17% over the 102-year period).”

Middle class Americans began paying income taxes in the 1930s. President Franklin Roosevelt “increased taxes, and, perhaps for the first time, reached into the middle class” to help fund the new government programs created under the New Deal to combat the economic crisis of the Great Depression. Since then, individual income tax has remained essential to our government’s revenue. In fact, the individual income tax has provided between 40% and 50% of total federal revenue since the 1940s. Today, individual income tax revenue is the federal budget’s single largest source of revenue.

Taxes have always been controversial, including the right of the government to tax citizens in the first place. While Article I of the Constitution authorized Congress to levy taxes, the Founders limited Congress’ ability to impose direct taxes on citizens by requiring that taxes be apportioned among the states, meaning that tax levels in each state had to be tied to population. The 16th Amendment to the Constitution removed this restriction, thus enabling Congress to tax at will.

Types of Taxes

Individual Taxes

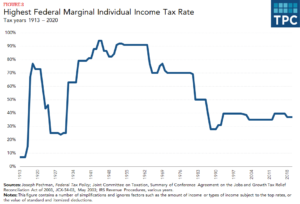

Individual taxes are levied upon individual taxpayers in the form of payroll and income taxes at the federal, state and sometimes local levels. At the federal level, payroll and income taxes generate the most revenue and pay for services from Social Security to national defense. State and local taxes can include income tax, sales tax, and property tax, which provide public services such as public schools and law enforcement. U.S. individual income tax rates have varied considerably over the last century. The top rate has dropped considerably from 70% in the early 1960s to 28% in the late 1980s but has risen since then, as the graph below illustrates. Many economists have taken advantage of the variation in taxes over time to study the effect of taxes on economic growth, often finding an inverse relationship between the two.

Individual taxes are levied upon individual taxpayers in the form of payroll and income taxes at the federal, state and sometimes local levels. At the federal level, payroll and income taxes generate the most revenue and pay for services from Social Security to national defense. State and local taxes can include income tax, sales tax, and property tax, which provide public services such as public schools and law enforcement. U.S. individual income tax rates have varied considerably over the last century. The top rate has dropped considerably from 70% in the early 1960s to 28% in the late 1980s but has risen since then, as the graph below illustrates. Many economists have taken advantage of the variation in taxes over time to study the effect of taxes on economic growth, often finding an inverse relationship between the two.

Meanwhile, the payroll tax (known on your pay statement as “FICA,” which stands for Federal Insurance Contributions Act) has overtaken the income tax as the federal tax that more Americans pay. A payroll tax is a tax paid on the wages of employees and is used to finance social insurance programs like Medicare and Social Security. All working Americans pay payroll taxes, but not all Americans pay income tax. This is due in part to payroll tax rate increases passed by Congress during the 1980s, and to measures that increased the progressivity of the income tax. Although the payroll tax is technically divided between the employer and the employee (in the form of withholdings, or money deducted from your paycheck), the employee ultimately bears its total cost in the form of lower take-home pay.

In 2018, 144.3 million taxpayers reported earning $11.6 trillion in adjusted gross income and paid $1.5 trillion in individual income taxes.

About half (51%) of federal government revenue comes from individual income taxes; another 31% comes from Social Security and Medicare taxes as part of payroll.

High individual tax rates mean that individuals, families, and small businesses have less income and less incentive to work, save, and invest.

General Corporate Taxes

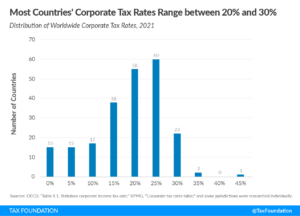

Corporate income taxes – taxes on the profits of businesses – comprise between 5-10% of federal revenue. The corporate income tax rate has fluctuated from 1% (1909-1915) to 52.8% (1968-1969). Today, the federal rate is 21% after the 2017 changes to tax legislation took effect. Many states also impose corporate taxes on businesses. Corporate income is generally subject to two levels of taxation, once when it is earned at the corporate level and again when income is distributed as a dividend to shareholders.

To avoid the double taxation of corporate income, many small business owners structure their businesses such that their profits are taxed at the individual rate. These “pass-through” businesses have been incredibly popular; between 1980 and 2014, the number of businesses organized as pass-throughs grew from 47% of businesses to 80%. This option is only available to closely-held business entities, including sole proprietorships, partnerships, and S corporations. All others are taxed at the corporate rate, which is graduated, similar to individual rates.

This two-minute Prager U video covers taxation on small businesses and pass-throughs:

Property Taxes

A property tax is a tax on a piece of owned property, based on the value of the property, including land. It is calculated by the local government where the property is located, and paid by the property owner. It is “a kind of user fee that residents pay voluntarily by their decision to locate in a particular community.” The average American household spends just under $2,500 on property taxes annually, but this varies by location. A 2021 study found that about 20% of homebuyers cited lower property taxes as a reason to move to a different area; see more about what is driving domestic movement in the U.S. in The Policy Circle’s Migration Between States Brief.

Property tax rates also usually represent the level of public services available; for example, property tax rates are a consideration for households with children as local school systems are primarily funded through local property taxes. Nationwide, property taxes pay for 37% of school budgets, on average; this can be as high as 59% in New Hampshire and as low as 13% in Alabama.

Key Terms to Know

Conversations surrounding tax policy usually focus on two main types of tax options: progressive and flat taxes. In a progressive tax system, as taxable income increases, it is taxed at a higher rate. This means different tax rates are levied on income in different ranges, called brackets. This is how the U.S. tax code operates, and it applies to both individual and corporate taxes. Here’s an example of a woman who makes $100,000 in a progressive system (such as in the U.S.): based on tax brackets, the first $50,000 she makes is taxed at 15% (50,000 x 15% = $7,500) and everything above that is taxed at 25% ($50,000 x 25% = $12,500) so she will pay ($7,500 + $12,500) $20,000 in taxes.

Khan Academy breaks down progressive tax brackets:

A flat tax, on the other hand, applies the same rate to all taxpayers. So, someone who earns $50,000 per year and someone who earns $100,000 per year pay the same percentage.

Prager U takes a closer look:

Consumption taxes are levied when people consume a good or service, and were used by the U.S. government for much of our history before being replaced with an income tax. Consumption taxes are thought to encourage savings and investment, behaviors that drive economic growth. However, some argue that consumption taxes are regressive, meaning they unfairly burden middle and lower income families more than high earners.

One example of a consumption tax is an excise tax, sometimes referred to as a “sin tax.” These taxes apply to a specific class of goods such as alcohol, tobacco, or gasoline. They are implemented as much in an attempt to change consumption patterns as to collect revenues. Excise taxes are a type of indirect tax, meaning the tax is passed off only to the consumer of the product in the form of an increased price. In the U.S., excise taxes account for about 3% of federal government revenue.

Another type of consumption tax is a value-added tax (VAT), “a tax on the difference between what a producer pays for raw materials and labor and what the producer charges for finished goods.” Essentially, it means the tax is levied on the “value added” to a good or service between production and consumption. More than 160 countries around the world, including Canada and most countries in the European Union, use VAT.

When it comes to calculating and paying taxes, deductions are usually expenses a taxpayer incurs during the year that can be subtracted from that taxpayer’s gross income, thus lowering the taxable income. Taxpayers can choose one of two types of deductions. Standard deductions are the portion of income not subject to tax. A taxpayer’s standard deduction is based on things such as filing status, meaning whether you are married, single, or have dependents or are claimed as a dependent on someone else’s tax return. With itemized deductions, a taxpayer lists all tax-deductible expenses for the year, such as medical expenses or eligible charity donations.

While deductions reduce the amount of taxable income, tax credits actually reduce the amount of tax a taxpayer owes. The most well known tax credits are the Earned Income Tax Credit and the the Child Tax Credit program. The latter made headlines after the coronavirus economic stimulus bill passed in March 2021 granted a one-year expansion of the tax credit for the 2021 tax year for many households.

The Role of Government

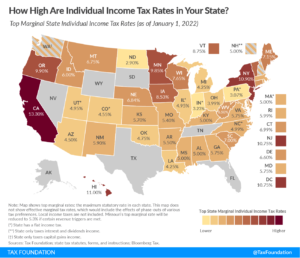

Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution gives Congress the power to “lay and collect taxes, duties, imports, and excises” to “provide for the common defense and promote the general welfare.” Governments pay for the services they provide with revenue obtained through taxes on income, consumption, property, and wealth. Individuals and businesses are subject to taxes by local, state, and the federal government. The federal government relies on income taxes as its primary source of revenue. State governments’ main sources of revenue are income and consumption taxes. Local governments rely almost entirely on property and wealth taxes. This map illustrates the income tax burdens levied by state governments. As you can see, the differences are substantial.

Fiscal Policy

The purpose of taxation should be to raise the revenue necessary to meet the government’s spending requirements while not distorting economic decision-making, or discouraging the spending, savings and investment potential for all Americans. During times of slow economic growth, it is particularly important to examine if the tax code reduces economic activity and whether fundamental reform is needed. This is the role of fiscal policy, the idea that “governments can influence macroeconomic productivity levels by increasing or decreasing tax levels and public spending.” For example, the government can stimulate the economy by lowering taxes to give consumers more spending money.

The looming debt crisis also makes spending restraint an urgent priority, since without that restraint it will be impossible to keep the tax burden on our economy from growing much heavier. Likewise, tax policy that spurs economic growth will in theory increase revenue for the government by generating more corporate and individual income that can be taxed, as well as generating more taxable economic activity for consumption-based taxes. The Congressional Budget Office and the Joint Committee On Taxation both analyze and run models for tax policy, giving much consideration to how businesses and individuals respond to tax changes.

For more, see The Policy Circle’s Economic Growth Brief and Federal Debt Brief.

Federal and state roles when it comes to taxation has created some friction. For example, the American Rescue Plan – included in the $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief packaged passed in the spring of 2021 – “provided $195 billion for state governments to help offset soaring costs related to the pandemic and plug budget holes stemming from the economic downturn” with the caveat that states could not use the money, “directly or indirectly, to cut taxes.” Arguing that the mandate is “overly vague, unconstitutional and would unfairly penalize states in good fiscal health,” there is a “showdown between states and the Treasury Department over the limits of the federal government’s fiscal authority.”

Another area of concern is in State and Local Tax (SALT) deductions. SALT deductions allow taxpayers “to deduct certain taxes paid to state and local governments” when filing federal taxes. The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act implemented a $10,000 cap on SALT deductions, when previously there had been no cap. Lawmakers in high-tax states like New York, New Jersey, and California have pushed for a repeal, as the deductions cap “disproportionately affected tax filers” in these high-tax states. Others argue a SALT cap “helps prevent the federal tax code from being used to subsidize high taxes levied by state and local governments.”

Challenges and Areas for Reform

Marginal Tax Rates

The marginal tax rate is the percentage of the next dollar earned that goes to the government. This is different from the average tax rate, the percent of income that goes to the government. One major difference between the two is that marginal tax rates affect incentives to work.

Let’s take the example from above of the woman making $100,000 in a progressive system (such as in the U.S.) that taxes the first $50,000 at 15% ($50,000 x 15% = $7,500) and everything above it at 25% ($50,000 x 25% = $12,500) will pay ($7,500 + $12,500) $20,000 in taxes. This makes her average tax rate 20% ($100,000 x 20% = $20,000) but her marginal tax rate is 25%, because every extra dollar she earns will be taxed at 25%.

Let’s say she makes $125,000. The first $50,000 is still taxed at 15% ($7,500) but the rest is taxed at 25% ($75,000 x 25% = $18,750), so she now must pay ($7,500 + $18,750) $26,250 in taxes. Her extra $25,000 results in an extra tax burden of $6,250, reflecting the marginal rate of 25% ($25,000 x 25% = $6,250). Additionally, her new average tax rate is 21% ($125,000 x 21% = $26,250). This increase in the average tax rate will happen every time she earns more money, either through working more hours or getting a promotion or raise. Thus she may not be motivated to work more.

For a visual guide, check out this breakdown of how marginal taxes work:

This is especially problematic for welfare programs, which “often impose high effective marginal tax rates that make it harder for low-income people to transition out of these programs and into the middle class.” For more on marginal tax rates and their adverse effects, see The Policy Circle’s Poverty Brief.

Property Taxes

One issue surrounding property taxes is that localities are heavily dependent on them. According to Steven P. Lanza, Associate Professor in Resident at the University of Connecticut Economics Department, governments usually mix taxes so no one type does all the work. However, states limit municipalities’ revenue-raising options, leaving property taxes to cover most services. This is why some tax experts argue that more balance among revenue sources could minimize other concerns with property taxes, such as when property values decline.

When property values decline, property tax revenue also declines, along with the services that must be pared down or canceled due to lack of funds such as garbage pick up or street light maintenance. The municipality would need to increase property tax rates to offset the lack of funds, but increased taxes on declining home values negatively impacts the households that live there. This is on top of disparities that already exist in valuing homes.

Analysis from University of Chicago concluded that local governments undervalue expensive properties and overvalue less expensive properties. This tends to result in poor and working-class families paying more of their income for housing, even when these lower-income communities struggle to provide critical services. One potential solution supported by experts like Gary S. Forshner, Adjunct Professor at Monmouth University’s Kislak Real Estate Institute, is to use a sliding scale for tax rates.

Forshner and many others also advocate for pooling tax revenue into a central account for equitable funding of public education and services. This could eliminate disparities, but others argue this could mean a household’s local taxes would cover services that the household would not be using. Another idea is to tax the value of land, rather than the value of property. This scenario would encourage building additional housing in denser forms so the tax on the land would be more distributed. This could ease housing supply issues, but would likely require changes in zoning laws, which can be difficult to implement. See The Policy Circle’s Housing Brief for more on zoning laws.

Income vs. Consumption Taxes

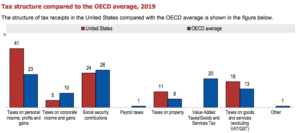

The debate of income vs consumption taxes boils down to whether to tax what people earn or what people spend. In the U.S., the main federal tax on individuals is the personal income tax “on both labor income (wages and salaries) and capital income (interest, dividends, and capital gains).” In fact, taxes on income and individual profits in the U.S. generated 41% of total tax revenue in 2019, compared to an average of 23% of total tax revenue among all other OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) countries. Critics of excessive reliance on income taxes note that a lower return on investment due to taxes disincentivizes saving and investment.

While the U.S. leans more on income taxes, other developed countries rely heavily on consumption taxes, such as the VAT that is common in Europe, or sales taxes in the U.S. By relying more heavily on VAT and other consumption taxes, these countries can maintain a lower income tax rate on both income from labor and capital (investment). Theoretically, this system encourages people to defer consumption and invest and/or save their income. Taxing interest, dividends, and capital gains, on the other hand, means less investment and savings than there would be in a tax-free world.

Critics of a consumption tax, however, maintain that while it does not punish wealth as income taxes do, it “places an increased economic strain on lower-income taxpayers.” Additionally, VAT is a more standardized option than a sales tax, but can add excess “bureaucratic burdens on businesses.” Finally, critics note that a substantially high tax rate would be required to raise the same amount of revenue as an income tax that includes capital income. An alternative somewhere in between in the U.S. is to modify the income tax to eliminate taxes on returns on investment such as capital gains, based on the argument that gains from additional saving and investment encouraged by removing capital taxes would cover losses in revenue. Econlib breaks the arguments down further.

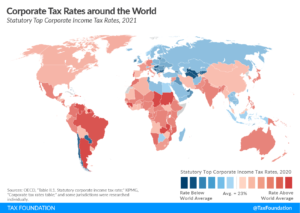

Corporate Taxes

Though the overall tax system in countries with consumption taxes is more regressive than the tax system in the U.S., (meaning that middle class consumption represents a larger share of government revenue), these countries are sometimes viewed as more competitive for business investment because of lower corporate income tax rates.

The general economic consensus is that high corporate tax rates inhibit business activity and can persuade companies from establishing offices in the country with higher rates. For a number of years, parent companies of many U.S businesses have chosen to relocate to countries that offer a better business climate, including lower tax rates, through a process known as “inversion.” Some companies choose to relocate manufacturing facilities for both lower tax and labor, thereby impacting job creation. Companies also tend to keep income generated outside of the U.S. in offshore accounts to avoid higher U.S. tax rates. The U.S. Treasury Department cracked down on this controversial practice in April 2016 with new regulations, and the 2017 tax legislation increased incentives for companies such as Apple to “repatriate” by lowering the corporate income tax from the highest rate of any developed country to closer to the average rate imposed by developed countries.

Kimberly A. Clausing, Deputy Assistant Secretary of Tax Analysis at the Treasury Department, explained in a testimony before the Senate Committee on Finance that even with the 2017 tax legislation changes, “U.S. companies continue to shift corporate profits offshore, reducing the U.S. corporate tax base and U.S. tax revenues.”

U.S. companies are not the only ones; Reuters explains that many major economies “are aiming to discourage multinational companies from shifting profits – and tax revenues – to low-tax countries regardless of where their sales are made. Increasingly, income from intangible sources such as drug patents, software and royalties on intellectual property has migrated to these jurisdictions, allowing companies to avoid paying higher taxes in their traditional home countries.”

The OECD and the G20 countries have tried to garner international cooperation on this since 2013, and Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has renewed a push for a global corporate minimum tax rate. In June 2021 the Group of Seven (G7 – Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the U.K., and the U.S.) agreed to support a minimum 15% global corporate tax rate. In October 2021, 136 countries agreed to the minimum rate; each will individually need to enact domestic legislation.

The Tax Gap

The tax gap is “the difference between taxes owed and tax collected,” and the IRS says this occurs due to errors, fraud, and lack of resources to enforce collections. The last time the IRS formally published data on the tax gap it used data from 2011 to 2013; at that time, the report showed annual losses of $441 billion. Since, the WSJ reports that “growth of cryptocurrencies and foreign-source income, as well as outside estimates that suggest a tax gap of $7.5 trillion over the next decade, mean past IRS research has almost certainly undercounted the losses.” IRS Commissioner Charles Rettig told the Senate Finance Committee the actual tax gap could be closer to $1 trillion per year.

Past estimates from the IRS itself “have suggested that it could bring in an additional $5 to $7 in revenue for each added dollar spent on enforcement.” Bipartisan consensus supports more highly skilled investigators and better technology to help close the tax gap, particularly in light of growing budget deficits and federal debt, which have ballooned in due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Taxes in Action: The Tax Cut and Jobs Act

The Tax Cut and Jobs Act (TCJA), passed in December 2017, was the biggest tax overhaul in the U.S. in 30 years. Here are some of the highlights:

Personal Taxes

The structure of seven income tax brackets remained unchanged, but rates and income bands within the brackets changed. For example, the top rate fell from 39.6% to 37%.

Deductions

The standard deduction nearly doubled under the TCJA, and itemized deductions at the state and local levels were limited to $10,000 annually. A likely effect of this will be far fewer taxpayers choosing to itemize deductions. Additionally, the laws increased the child tax credit and created a non-refundable credit for non-child dependents. Other deductions, including moving expenses, licensing and regulatory fees, and union dues, were suspended.

Affordable Care Act Individual Mandate

The Affordable Care Act required households without qualifying health insurance to pay a penalty. As of January 2019, the TCJA essentially eliminated this penalty by reducing it to $0. For more on the Affordable Care Act and its status, see The Policy Circle’s Affordable Care Act Deep Dive.

These tax provisions (with the exception of the ACA mandate tax) are set to expire after 2025. The Tax Policy Center goes more in depth on these personal tax changes. Changes to taxes on businesses, on the other hand, are mostly permanent.

Corporate Tax Rate

One of the most significant changes implemented by the TCJA was the reduction of the top corporate income tax rate from 35% to 21%, which brought the U.S. rate down from being one of the highest among developed nations to average.

Pass-through Income

Pass-through businesses – which include sole proprietorships, partnerships, and S-corporations – pay taxes of their firms earnings at the individual income tax rates. The TCJA creates a 20% deduction for pass-through business income (with some exclusions based on income levels).

Foreign Earnings

U.S.-based firms and corporations have a strong incentive to shift investments and profits to countries or jurisdictions overseas with no taxes or taxes lower than what they are in the U.S. The TCJA introduced a tax system designed to reward repatriation of overseas profits while penalizing shifting profits overseas. For example, it introduces a deduction for foreign-derived intangible income (FDII). This refers to intangible property like patents, trademarks, and copyrights; a pharmaceutical company would then be able to deduct income from overseas drug sales if the patent on the drug is held in its US parent company. Based on early evidence, it is unclear whether these efforts have fewer companies to shift investments and profits elsewhere.

Both Investopedia and the Tax Policy Center take more in-depth looks at the changes from the TCJA.

Effects

Growth

At the start of 2017, the U.S. had a rather low growth rate, especially compared to the rapid growth from the end of World War II to 2007. The argument in support of the The TCJA was that “the accumulation of physical and intangible assets, the location of that capital in the United States, and the efficient allocation of that capital across businesses, sectors, and asset types” would result in higher productivity. Economists do not currently agree on whether or not the TCJA increased business investment. American Action Forum President Douglas Holtz-Eakin notes that the growth rate of investment and the growth rate of labor productivity steadily increased after 2017, and that the tapering off in 2019 coincided with impacts from trade tactics. The IMF concluded (pdf) that business investment growth was stronger than had been anticipated, but noted data from a survey indicated only 10-25% of businesses attributed their planned increases in investment to the tax code changes and that increases in aggregate consumer demand spurred investment.

American Families

Many analyses show that most families did receive a tax cut; the Tax Policy Center calculated an average household paid about $1,600 less in 2018 than they would have without tax code changes. Aparna Mathur of the American Enterprise Institute (AEI) notes that personal income grew 4% in 2018, showing labor market improvements, but whether that is the result of the TCJA or post-recession recovery is still unclear.

A second large effect on American families has been changes in tax refunds. According to IRS statistics released in February 2020, the total number of refunds issued fell by about 3% from February 2019. Tax refunds are essentially delayed earnings – if too much tax is withheld from someone’s earnings, that person is owed money by the IRS. Due to withholding changes from the TCJA, many taxpayers that didn’t adjust their paycheck withholdings received larger paychecks and therefore smaller refunds. For many consumers that live paycheck to paycheck, receiving a tax refund is mostly an expectation; according to H&R Block CEO Jeff Jones, 86% of Americans say their tax outcome makes or breaks their financial confidence for the year, even though a smaller refund really means they did not overpay the government in the first place. As of 2022, this has evened out; totaled refunds filed increased from 2021 to 2022.

Corporations

Since the corporate tax rate was substantially lowered, it is no surprise that corporate tax revenues are also substantially lower than they were before the tax rate was reduced. The corporate income tax revenue in 2017 was just shy of $300 billion; in 2019, it was $230 billion. Additionally, Aparna Mathur of AEI found repatriations (U.S. companies bringing back profits into the U.S.) saw a massive increase at the start of 2018. Many economists saw the rate cut as important for U.S. competitiveness on the global stage, while others saw a giveaway to corporations that had little impact on investment and workers.

In 2021, corporate income tax revenue was $370 billion, an increase of 75% over 2020 and an all time high reflected by the economy rebounding after the pandemic.

Key Takeaways

Nothing in the economy happens in a vacuum, especially tax cuts – other economic happenings are always in play. The law’s design is for long-term economic impact, so it is difficult to say what the overall economic effects are, or what they will be, particularly since the economy has been so heavily affected by the coronavirus pandemic.

The inherent complexity of the economy, and the mixed results of our attempts to impose our will upon it, is why the free-market Mercatus Center think tank offers the goal of simplicity. Tax season is met with stereotypical moaning and groaning. This is not likely to end, but a simpler tax code can certainly make compliance much easier. A simpler tax code will also result in less interference with market behavior. In turn, this means a simple tax code is one that is predictable, which can help businesses and individuals learn what to expect and be more certain in their choices for growth and investment. Finally, many Americans believe the tax code is unfair because of “loopholes.” A simpler tax code can promote fairness by reducing or entirely eliminating provisions that favor some groups or activities over others.

Conclusion

Benjamin Franklin famously wrote in a letter that “nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” As long as there are essential government services, we can be sure they will be financed with taxes. What we do have power over in the tax system, however, is ensuring taxes are simple, equitable, and sustainable.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Find out what your state and district are doing about taxation.

- Do you know about your state’s budget and finances?

- What are your state’s tax policies?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Who are the members of the departments of treasury, revenue, or taxation in your state?

- What steps have your state’s or community’s elected and appointed officials taken?

- Has there been any recent tax-related legislation in your state?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with neighbors, community organizations, and local businesses or entrepreneurs.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, communications@thepolicycircle.org, for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policy makers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Investigate you own finances – how much is taken out of your paycheck in taxes?

- Reach out to local business owners and entrepreneurs about their tax burdens, or to your local chamber of commerce.

- Investigate how your state compares to others in terms of tax revenue from income, sales, and corporate taxes.

- See the National Conference of State Legislature’s State Tax Actions Database for recent actions in your state.

- Consider contacting a tax professional in your community to hear their thoughts about tax policy in your state.

- Write to your federal, state, or local government officials about your interest in tax policy.

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.

Thought Leaders and Additional Resources

For tax policy specifically:

- Americans for Tax Reform, the enforcer of the Taxpayer Protection Pledge

- The Tax Foundation

- The Tax Policy Center

- The National Taxpayers Union

These think tanks also have top-notch scholars who promote free-market policies with an eye towards economic growth and limited government:

- The Mercatus Center at George Mason University

- Manhattan Institute

- American Enterprise Institute

Videos on Taxes:

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.

State Briefs

Want to learn more about how states are dealing with this issue? Read our state-specific briefs below: