Introduction

Watch The Policy Circle’s Move the Needle Virtual Experience featuring a discussion on literacy in America. This conversation features British Robinson, President and CEO of the Barbara Bush Foundation; Dani Hedlund, Founder and CEO of the Brink Literacy Project; and Anne Wicks, Director of Education and Opportunity at the Bush Institute:

View the Executive Summary for this Brief

“Once you learn to read, you will be forever free,” Frederick Douglass, abolitionist and statesman.

When Brandon Griggs took his middle school exams, he didn’t care whether he passed or failed. He was preoccupied with the fact that he didn’t have electricity or food at home, let alone access to the internet or a home computer. In addition to multi-generational challenges of survival, Brandon’s schools were broken — providing sub-par instruction, inadequate funding, and limited resources. Ultimately, Brandon received the lowest possible score on his state exams. He witnessed his friends turn to crime because it was the easiest way to make a living. “Only 16% of African-American youth are proficient in reading by the time they reach high school,” Brandon shared during a 2019 Tedx Talk titled The Illiteracy to Prison Connection. “In many cases, by the time we realize that it is the case, it is far too late to reverse the damage that has been done to them by our broken schools.”

The only way to learn to read and write is through proper education and instruction. Literacy impacts nearly every aspect of daily life, including pursuing a career, attaining financial independence, and navigating healthcare. Literacy influences how people understand the world and dictates how they navigate their life choices.

According to the 2019 Nation’s Report Card, issued by the U.S. Department of Education, more than 60% of U.S. public and non-public school students were below grade level in reading. In the United States, 54% of American adults read below the equivalent of a sixth-grade level, and nearly one in five adults reads below a third-grade level. In the latest 2022 Nation’s Report Card that specifically tested the reading levels in fourth and eighth grade students, both grades demonstrated an increase in the number of students below the NAEP Basic reading level.

This Policy Circle Brief will explore literacy in the United States, including the change in literacy rates over time, the impact of the pandemic on literacy among our youth, the variance of literacy results across different demographic groups, and the policy changes proposed to improve literacy.

Why It Matters

Low literacy is defined as being unable to complete tasks related to comparing and contrasting, paraphrasing, or making low-level inferences. With low literacy rates, we see inequities continue to widen as low literacy correlates with:

- higher unemployment;

- reduced income;

- higher incarceration rates; and

- poorer health outcomes.

As reported by the Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy, the children of parents with low literacy levels have a 72% chance of being at the lowest level of literacy when they become adults, creating a cycle of illiteracy and poverty that can span generations. A Gallup study commissioned by the foundation estimated that raising every American adult’s literacy rate to a 6th-grade reading level would generate an additional $2.2 trillion a year for the U.S. economy.

Higher literacy levels also have a positive impact on non-economic outcomes, according to a study from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). This study found a correlation between higher literacy rates and trust in others, political efficacy, participation in volunteer activities, and self-reported health.

While some programs focus on improving literacy among adults, multiple studies show that investment in reading skills during early childhood programs produces more effective long-term results. Students who master literacy skills have the fundamental skills needed for academic success and better employment opportunities as adults. According to ProLiteracy, an estimated $106–$238 billion in annual healthcare costs are linked to low adult literacy skills in America.

With challenges to improve both childhood and adulthood literacy skills, it is critical to note that it is not an either-or programming solution, and both K-12 and adult literacy programs must garner attention and funding.

See The Policy Circle Briefs on Health Disparities & Determinants of Health and Financial Literacy for more information on these topics.

Putting It Into Context

Definition

The Oxford dictionary defines literacy as “the ability to read and write.” UNESCO goes further, defining literacy as “the ability to read and write, to understand, interpret, create, communicate and compute, using printed and written materials associated with a diverse context.”

However, there are also levels within literacy, ranging from low to high. The Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), a test of adult skills, ranks literacy skills from 1-5. The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) defines “Low English literacy” as those performing at PIAAC literacy proficiency Level 1 or below or who could not participate due to a language barrier or a cognitive or physical inability to be interviewed. “Mid or High English literacy” refers to those performing at PIAAC literacy proficiency Level 2 or above.

Historically, in the United States and around the world, access to literacy was used as a tool for oppression. When the abolitionist and statesman Frederick Douglass was a young boy in Maryland in the 1820s, anti-literacy laws in the state forbade people from teaching enslaved people how to read and write. By teaching literacy, the laws argued, people would become liberated. Similar arguments were made to prevent women from learning to read. “Once you learn to read, you will be forever free,” Douglass said.

By The Numbers

Measuring Literacy

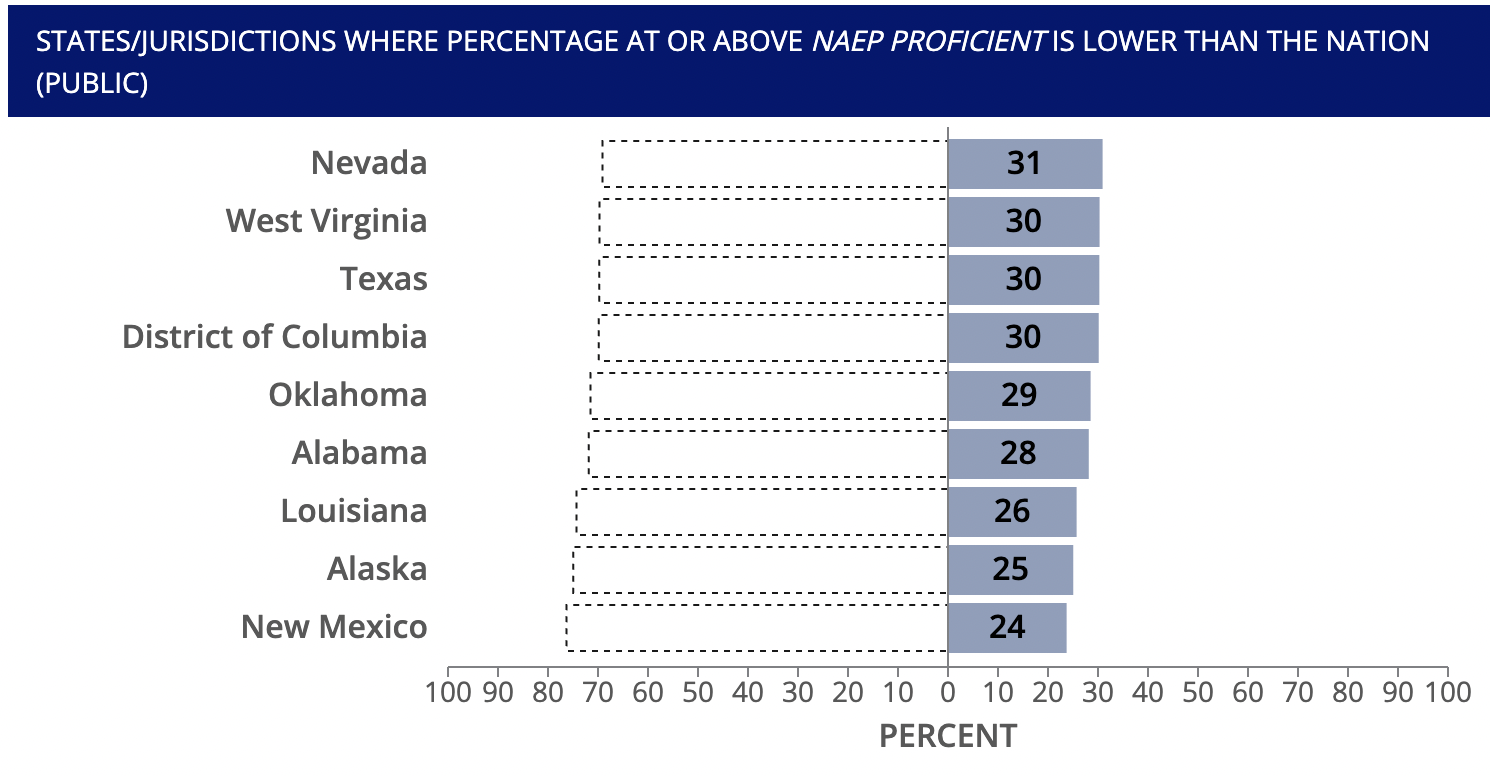

Students in K-12: The United States measures literacy in children through the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), which publishes its findings through the Nation’s Report Card. The NAEP, a congressionally mandated project of the U.S. Department of Education, administers reading assessments to the country’s students in grades 4, 8, and 12. Results from the most recently published data from 2019 show that less than 40% of students in public and non-public schools were reading at or above grade level. Less than 30% of students met that threshold in large city public schools. The states with the lowest percentages of students reading at grade level were the District of Columbia, Texas, and West Virginia (all with 30% of students reading at grade level), Oklahoma (29%), Alabama (28%), Louisiana (26%), Alaska (25%) and New Mexico (24%).

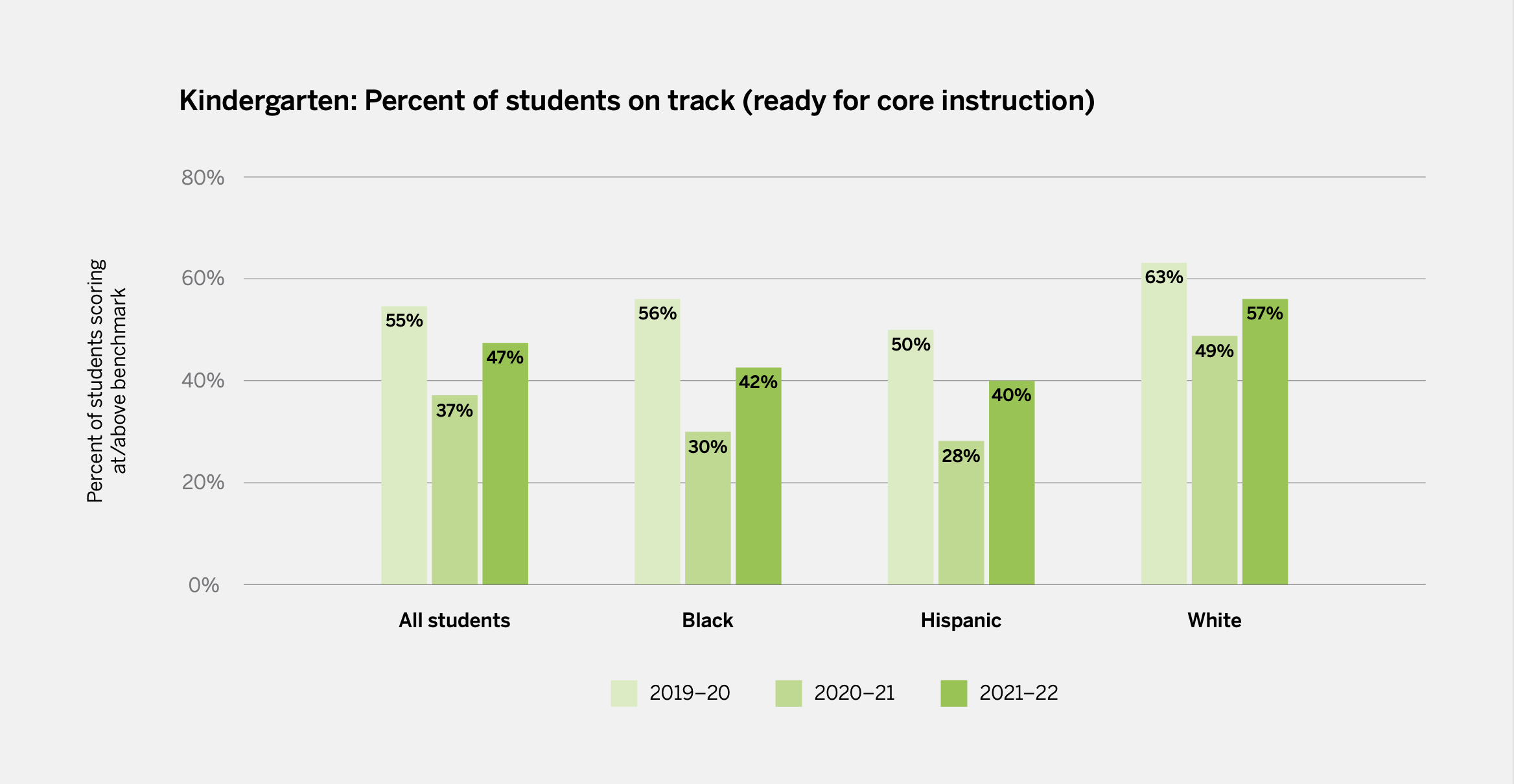

Multiple studies have found that the reading levels in school-aged children in the United States have decreased even further since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The decreases in literacy rates are highest for children in grades K-2. Further decreases also can be found along demographic lines, with more significant gaps between higher-and lower-income pupils, as well as among White students and Black and Hispanic ones. In the fall of 2020, 37% of kindergarteners in the United States were on track to learn to read, down from 55% a year earlier – this trend continued across all elementary-school students.

While the studies showed that returning to in-person learning did increase literacy rates, by 2022, literacy rates were still below 2019 numbers.

Adults: In the United States, 4 in 5 adults are literate, but more than 130 million adults have low literacy skills. That equates to about 1 in 5 adults reading at or below a Level 1, which means they have difficulty understanding printed or digital materials. National averages show that 54% of adults read at or below the equivalent of a sixth-grade level. Further, a critical component of adult literacy also ties into the parent/child literacy connection, in which parent involvement serves as one of the largest predictors for early literacy achievement. There are many factors to consider when measuring the impact of literacy in the United States, including:

- Of adults with low literacy, 10% receive support services, such as adult-literacy programs;

- 43% of adults with the lowest literacy skills live in poverty;

- One-third of adults with low literacy are unemployed;

- White adults make up 35%, and Hispanic adults make up 34% of U.S. adults with low levels of English literacy;

- Immigrants comprise 34% of the population with low literacy skills; and

- Those who are employed have an average annual income of $34,000, nearly two times lower than workers with higher literacy levels.

The average adult literacy score in the United States was below the international average, with the United States ranking 13th out of 24 countries tested. Literacy levels vary across states as well. According to data from PIAAC, the states with the highest adult literacy rates were New Hampshire, Minnesota, North Dakota, Vermont, and South Dakota. States with the lowest literacy rates were California, New York, Florida, Texas, and New Jersey. (For a complete list of statistics by state, look here.)

Low education levels in adults are also correlated with higher incarceration rates. According to the most recent study available, the 2016 PIAAC prison study, 94% of incarcerated adults had a high school degree or below, compared with 64% of adults in the general population. According to the same study, 29% of inmates had low literacy (below a level 2), compared with 19% of the general population. A 2013 Rand Corporation study found that inmates that participated in education programs were 43% less likely to return to prison after their release. Several organizations focus on increasing literacy rates for incarcerated adults to address the issue. The Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy highlights the following programs:

- The Petey Greene Program, one of the most extensive multistate volunteer tutoring programs, has over 1,000 volunteer tutors from 30 different universities reaching 50 correctional facilities;

- In Massachusetts, The Hampden County Sheriff’s Department offers adult literacy courses, special education, vocational training, and credit courses with local colleges; and

- The Coalition on Adult Basic Education launched a committee to bring adult education programs into prisons across the country.

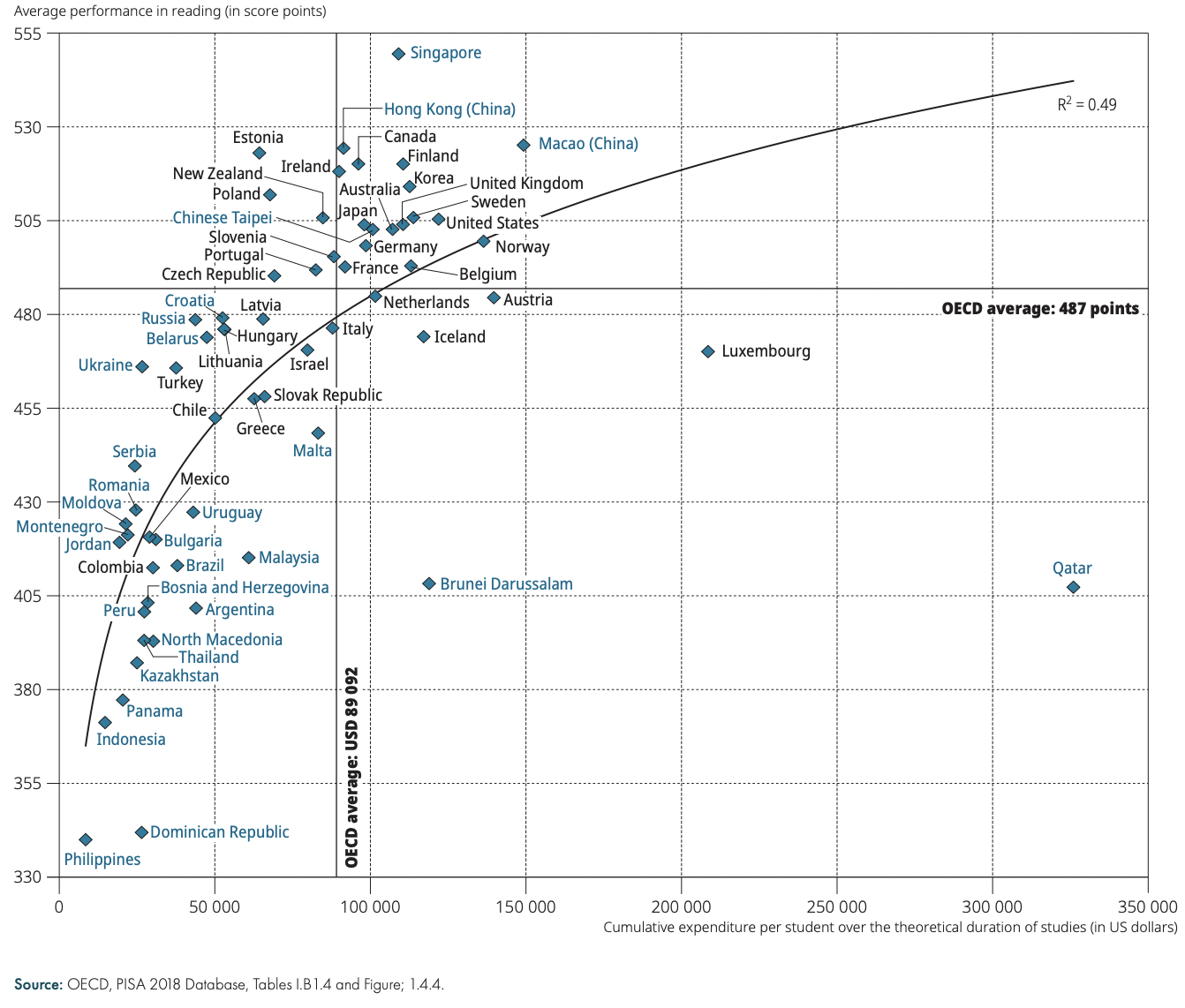

The United States Global Literacy Ranking: Literacy rates for students in the United States have not increased since 2000, according to the 2018 results of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), an international exam administered by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The United States ranked 13th out of 79 countries and regions for reading levels; the United States ranked 37th for math. (The PISA rankings divide Chinese provinces as separate regions, stating that each province is comparable to a typical OECD country. With both sets of rankings, three Chinese provinces had higher scores than the United States.) The PISA results also show a correlation between education spending and literacy rates, but only up to a point.

Funding

According to PISA data, the United States spends over $100,000 per student on education throughout their entire K-12 education. This is higher than the OECD global average of $89,000 per student. The only countries/provinces that spend more per student are Norway, Austria, Macao (China), Luxembourg, and Qatar; of those countries, only Macao had higher reading scores than the United States. The United States spends more on education than Canada, Ireland, and New Zealand, but its reading scores are lower than those countries.

According to U.S. Census Bureau data, per-pupil annual spending averaged $13,494 in 2019-20, which was the ninth consecutive year with an increase. Spending varied considerably by region, with the Northeast averaging $21,123 per pupil and the West averaging $12,802 per pupil. States that spend the most per pupil were New York ($25,520), the District of Columbia ($22,856), and Connecticut ($21,346). States that spent the least per pupil were Idaho ($8,272), Utah ($8,366), and Arizona ($8,785). In contrast to K-12 education, the United States spent an average of $438 per student per year for basic adult education classes.

Approximately 92% of funding for education spending is generated via state, local, and private sources. For example, over 80% of funding for public school districts came from local property taxes in 2016-17. The Department of Education maintains a database of federally funded state programs. For general information on school funding, see The Policy Circle’s Education: K-12 Policy Brief.

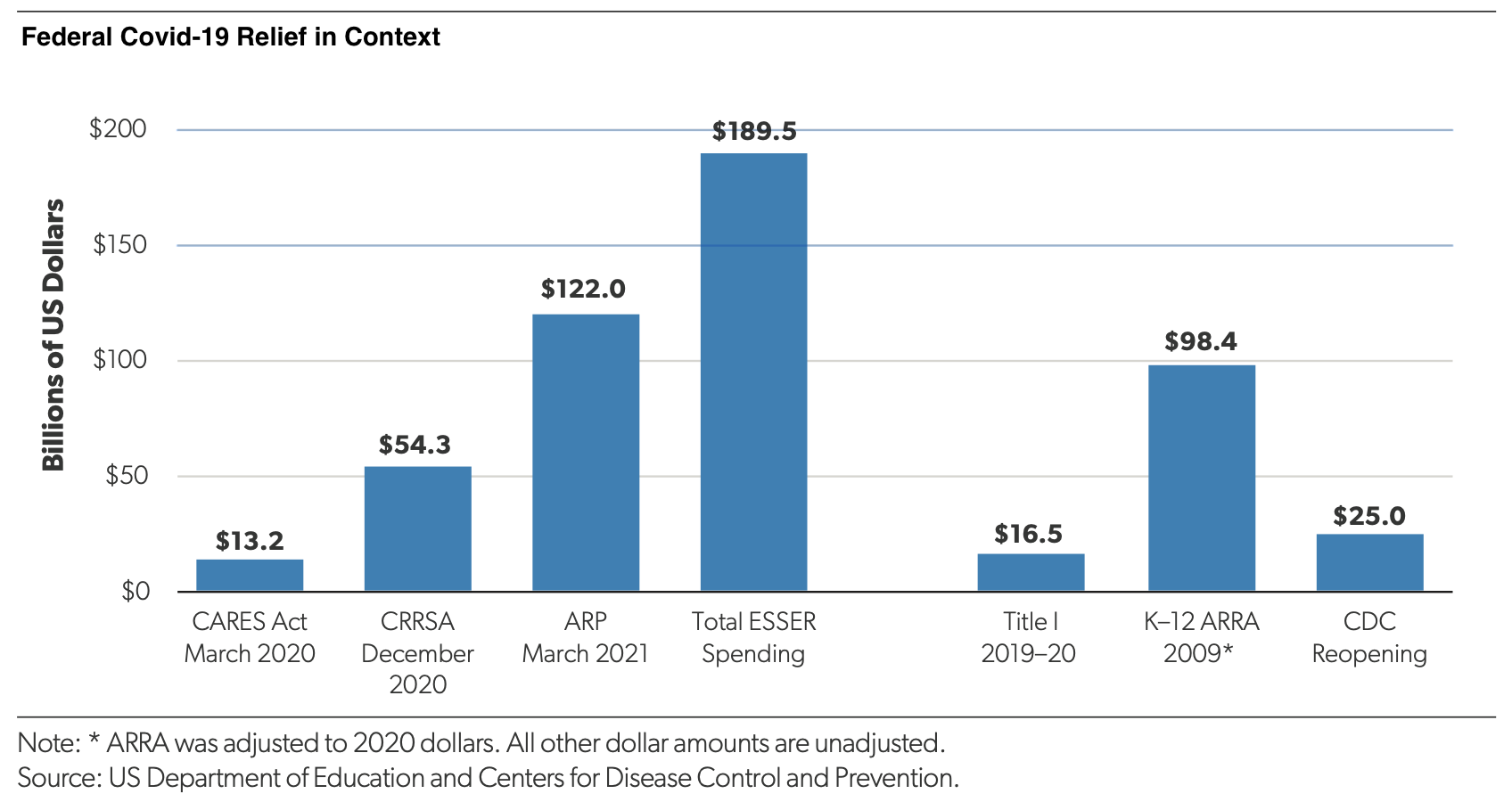

Since the pandemic, the federal government provided an additional $190 billion to schools through three legislative acts, across two administrations, referred to as Elementary and Secondary Schooling Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds. ESSER funds distributed under the Biden administration were part of the larger American Rescue Plan Act. The federal government granted these emergency relief funds to help address the impact that the COVID-19 pandemic had on schools across the country.

The Role of Government

Federal

According to the Department of Education budget for 2022-23, the federal government requested $88.3 billion for the department, up $15.3 billion from allocations in 2021-22.

The following Congressional committees work on issues related to education:

- The U.S. Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, as well as the subcommittee on children and families; and

- The House Committee on Education and Labor.

The federal government has a limited role in education policy, as the policy and funding dedicated to education is primarily a state and local responsibility. This stems from the Tenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which says: “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” However, since President Andrew Johnson first signed legislation to create an Office of Education in 1867, subsequent administrations have wrestled with how much the federal government should influence education policy.

According to the Department of Education, the Office of Education was designated as an “office” and not a cabinet-level “department” specifically to ensure it would not infringe on states’ rights. However, between 1867 and 1980, the Office of Education grew as the federal government enacted several critical pieces of legislation relating to education. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter consolidated several government agencies into the current Department of Education, creating a cabinet-level department. Each president appoints a Secretary of Education, who runs the department during the president’s administration.

According to the department’s mission statement, it has the following main tasks:

- Establishing policies on federal financial aid for education and distributing and monitoring those funds;

- Collecting and disseminating data;

- Focusing national attention on educational issues; and

- Prohibiting discrimination and ensuring equal access to education.

The Department of Education also maintains a database of appropriations, broken down by state and program, which includes the most up-to-date funding allocations for each program. The following vital programs are ranked here by the amount of funding received in 2020:

- Pell grants;

- Title 1 grants;

- Special education;

- The federal student loan program;

- And impact aid.

The National Defense Education Act (1958)

While federal legislation before World War II focused on domestic issues within the United States, the start of the Cold War with the Soviet Union marked a turning point in which U.S. policy aimed to ensure the competitiveness of Americans globally. According to the Department of Education, Congress passed the National Defense Education Act (NDEA) in 1958 in response to the Soviet Union’s successful launch of the Sputnik satellite into space, with a budget allocation of over $1 billion. The House of Representatives’ original report on the bill states: “It is no exaggeration to say that America’s progress in many fields of endeavor in the years ahead–in fact, the very survival of our free country–may depend in large part upon the education we provide for our young people now.”

The Elementary and Secondary Education Act (1965)

The Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 (ESEA), created as part of President Lyndon Johnson’s “War on Poverty,” ushered in an era of increased federal involvement in education and provided the foundation for many current education policies. ESEA increased the Department of Education’s budget from $1.5 billion to $4 billion in the two years following enactment.

Since 1965, Congress has reauthorized the ESEA several times, most notably through the 2002 No Child Left Behind Act and the 2015 Every Student Succeeds Act.

Significantly, the ESEA created the Title I program to authorize federal aid for children living in poor urban and rural areas. With $16.5 billion in funding in 2021, Title I is still one of the most extensive federal programs in 2022, second only to Pell Grants in the amount of funding it received.

To ensure that states continued to have autonomy, the ESEA gave money directly to states, which then funded the individual schools within their borders. The original 1965 ESEA deployed funds to improve literacy in schools in the following ways, many of which formed the groundwork for future legislation in subsequent administrations:

- Family literacy services for students in schools where a “substantial” number of parents have low literacy levels, limited English proficiency, or do not have a high-school diploma;

- Federal grants for textbooks;

- Aid for schools to develop libraries;

- State-based literacy instruction plans for reading and writing from early education through grade 12; and

- Subgrants to states for early childhood programs, local agencies, and public and private organizations to provide literacy instruction to students in need.

The Individuals with Disabilities Act (1975)

In 1975, the Ford administration passed the Individuals with Disabilities Act (IDEA), which guarantees access to a “free appropriate public education” to every child with a disability. IDEA provided services to more than 7.5 million students in the 2018-19 school year. IDEA also grants states to support special education and early intervention services, along with discretionary funds for state educational agencies, technology, and parent training.

No Child Left Behind (2002)

In 2002, President George W. Bush signed No Child Left Behind (NCLB), a reauthorization of the 1965 ESEA, into law. NCLB increased federal regulation of school systems by requiring states to administer yearly tests in reading and math in grades 3-8 and at least once in grades 10-12. According to Ballotpedia, NCLB resulted in total federal funding for education increasing by nearly 50%, from $35.6 billion in 2000 to $53.1 billion in 2003. This included $11.1 billion in grants for special education, $2.9 billion in subsidies for improving teacher quality, over $2 billion for administering state assessments and $1 billion for the Reading First program.

NCLB also required states and school districts to provide families with “report cards” on schools and districts that included data on achievement by race, ethnicity, gender, English language proficiency, migrant status, disability status, and low-income status. It also tied federal funding to the academic progress of schools.

When NCLB passed, only 32% of fourth graders read at a “proficient” level, with large gaps between the country’s highest- and lowest-performing students. The parent’s guide stated the NCLB aimed to increase literacy in the following ways:

- Providing federal funding for reading teachers in early education and other programs that “scientifically based research has shown to be effective”;

- Providing federal funds to early-childhood programs before Kindergarten to develop pre-reading skills;

- Requiring all schools that receive Title I funding to involve parents in programs;

- Ensuring schools teach students phonemic awareness, phonics, reading fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension; and

- Using yearly tests ensures that all students are “proficient” in reading and math.

However, NCLB also had critics, including the education secretary under President Barack Obama, who stated in a speech that the law “created dozens of ways for schools to fail and very few ways to help them or reward success.”

Race to the Top (2009)

Facing criticism of No Child Left Behind, the Obama administration instituted new policies to address literacy. One education policy, Race to the Top, provided $6 billion in grants to schools that met the following criteria:

- Developed “rigorous” and “common” standards for assessments;

- Gave parents data about students; and

- Helped with interventions for the “lowest-achieving schools.”

Though Race to the Top did not explicitly call for adopting Common Core State Standards, 48 states adopted these in the aftermath of Race to the Top to receive grants. Under the Common Core State Standards, each grade level had to set quantifiable benchmarks in reading and math.

Every Student Succeeds Act (2015)

In 2015, the Obama administration passed the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), which the Congressional Budget Office initially estimated would cost $23.9 billion in 2016, with an additional $142.2 billion from 2016-2020.

Under the ESSA, accountability for schools shifted to the states. For example, schools still had to administer standardized tests, but rather than meeting federal standards states could set their own performance goals.

The ESSA addressed literacy in the following ways:

- Continuing standardized tests for reading while shifting accountability from the government to the states;

- Adopting Common Core standards for teaching and testing English and math;

- Authorizing a program called Literacy Education for All, Results for the Nation (LEARN); based on “scientifically based research;”

- Supporting literacy programs in low-income communities; and

- Increasing funds for school libraries.

Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (2020-21)

In the first 100 days of his presidency, Donald Trump issued an executive order limiting the federal government’s role in education, saying: “It shall be the policy of the executive branch to protect and preserve state and local control over the curriculum program of instruction, administration, and personnel of educational institutions, schools, and school systems, consistent with applicable law.”

However, within a few years, the closures of school buildings in March 2020 amid the COVID-19 pandemic pushed the Trump administration to help pass the first of three Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief funds (ESSER), initially giving schools $13.2 billion in grants. Within the next year, Congress, under both the Trump and Biden administrations, would pass two additional ESSER funds, with an additional $54.3 billion and $122 billion, respectively, in education grants. Overall, between March 2020 and March 2021, the federal government provided $190 billion to schools through ESSER.

Several components of ESSER aim to address the decline in literacy, including the following programs:

- The Adult Education and Family Literacy Act, with $674,955,000 for adult education grants in 2021-22;

- Increased funds for what the legislation calls “evidence-based practices” to support early literacy programs;

- Programs that increase literacy rates in English language learners and students with disabilities;

- Professional development to staff in early education and grades K-12 for early intervention in “scientifically based” literacy instruction;

- Parent training and family literacy programs;

- Pre-K and early-childhood programs to teach early literacy; and

- Classroom cleaning so that adults can access them for literacy programs in the evenings.

A report from the Brookings Institution states that as of mid-2022, it was too early to see if the $190 billion in emergency funding through ESSER would offset the learning loss students experienced during the pandemic and related school closures. Another report from the American Enterprise Institute questions how much of ESSER funds will actually go toward addressing learning loss connected to the COVID-19 pandemic, noting that ESSER funding is 11 times annual Title I spending and nearly five times total federal K-12 spending in 2019-20.

State

According to the federal Department of Education, “education is primarily a State and local responsibility in the United States.” Ultimately state governments decide education policy, address literacy levels in their states and decide the extent that they allow innovation and parental choice in education.

State boards of education manage requirements in their states and have the following key responsibilities:

- Establishing schools and colleges;

- Developing teaching standards and curricula;

- Developing testing requirements and measures of academic performance; and

- Determining requirements for enrollment and graduation.

Members of state boards of education are selected in various ways:

- Governors appoint state boards for a fixed term in 30 states;

- In 10 states, state boards are elected on ballots;

- In three states (New York, Pennsylvania, and South Carolina), the legislature appoints the boards;

- In four states (Louisiana, Mississippi, New Mexico, and Ohio), the state boards include elected and appointed members; and

- In Washington state, the board consists of elected school board members and one member elected by private schools.

The National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) maintains separate databases to track state-level education legislation on a wide range of topics, including accountability, education finance, high school graduation, dropout rates, religion in schools, school choice, and school safety. For general education information, see The Policy Circle’s Education K-12 Brief.

education legislation on a wide range of topics, including accountability, education finance, high school graduation, dropout rates, religion in schools, school choice, and school safety. For general education information, see The Policy Circle’s Education K-12 Brief.

Since the passage of the 2015 Every Student Succeeds Act, states have set standards for the performance of students in their schools. Each state submits an ESSA consolidated state plan to the federal Department of Education, which includes individual state profiles, summaries of elements of the state plans, and relevant legislation. The ESSA State Plan database includes state-by-state benchmarks for reading, literacy, and graduation rates, along with state-specific legislation. The federal Department of Education maintains a database of key state contacts, including each state’s departments of education, special education, and adult education.

The Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies includes a breakdown of adult literacy scores by state. The National Assessment of Education Progress includes state data on reading levels for children. The latest data shows that the state-average scores for fourth-grade reading levels were lower in 17 states in 2019, compared with 2017, while 34 states reported no change. Further decreases since 2020 are expected due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to the data, no state had a majority of students reading at or above grade level. The states that ranked highest in fourth-grade reading levels were Massachusetts (45% of students reading at grade level), New Jersey (42%), Wyoming, Connecticut, Utah, Pennsylvania, and Colorado (all at 40%). The states with the lowest percentages of students reading at grade level were the District of Columbia, Texas, and West Virginia (all at 30%), Oklahoma (29%), Alabama (28%), Louisiana (26%), Alaska (25%) and New Mexico (24%).

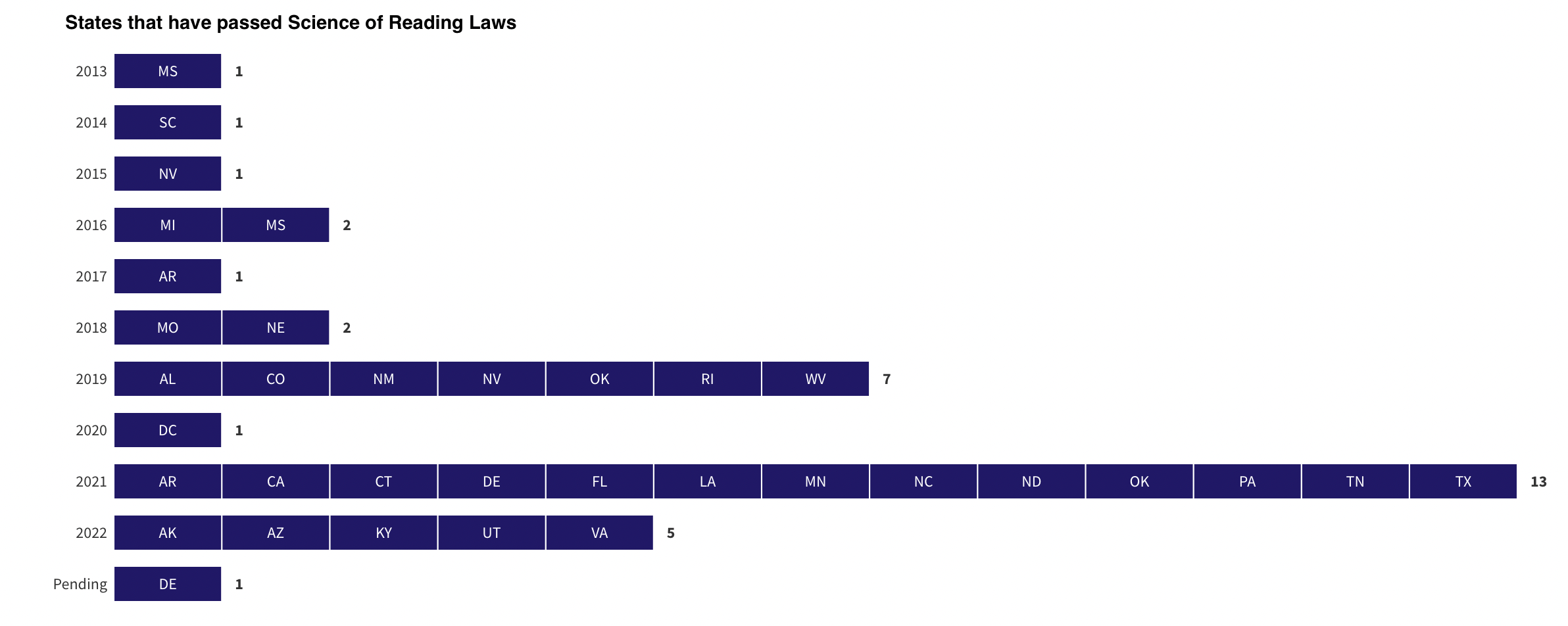

Only one state, Mississippi, recorded an increase in its state reading levels between 2017 and 2019. Various reports have offered a wide range of reasons for Mississippi’s increase in reading achievement, including early-literacy programs and professional development using Common Core standards, in addition to an increased focus on the “science of reading.” Statistics also show Mississippi holds back a higher percentage of K-3 students who do not master skills – more than any other state.

early-literacy programs and professional development using Common Core standards, in addition to an increased focus on the “science of reading.” Statistics also show Mississippi holds back a higher percentage of K-3 students who do not master skills – more than any other state.

Eight states offer programs for families to choose schools or supplement resources (such as tutoring, textbooks, or online courses) through Education Savings Accounts (ESAs), including Arizona (the first state to implement ESAs), Florida, Indiana, Mississippi, New Hampshire, North Carolina, and Tennessee. In Arizona, 90% of the money the state would have paid for a child to attend a charter school is deposited into a parent’s account.

Local

Within each state, regions are broken into local school districts. The number of districts per state varies widely; individuals can look up their local school districts here.

Public schools in these districts are governed by school boards that are elected or appointed by the city’s mayor. Local school districts authorize charter schools, which are publicly funded but operate independently of local school boards and government guidelines. Most importantly, local governments create budgets for their districts. School districts develop educational policies, decide to open or close schools, and hire staff. For more information about how local school boards operate, see The Policy Circle Understanding School Boards Brief.

Private Sector and Nonprofit Programs

The United States has many private sector and nonprofit organizations focused on increasing literacy rates. The National Literacy Directory includes a database of literacy programs throughout the country. Other organizations that work on literacy include the following:

- Save the Children, a U.S-based program that helps fund literacy programs both within the country and worldwide. In the United States, the program focuses on rural communities living with economic difficulties.

- Believe in Reading provides grants for literacy programs to nonprofit organizations. It has funded 245 programs, including the purchases of books for local libraries and children in migrant camps, tutoring for at-risk children in early education, and the purchases of test-prep books for adults.

- ProLiteracy focuses on increasing adult literacy through programs and grants. It also provides a database of grants available for literacy programs.

- The Junior Library Guild provides grants to build libraries.

- Take Stock in Children, a Florida-based program, provides mentoring and college scholarships to academically qualified students from low-income neighborhoods.

- Barbershop Books, approaches literacy in the context of families and communities, in addition to providing culturally relevant reading material

- Bernie’s Book Bank, a Chicago-based nonprofit organization, distributes books to children in need to increase literacy.

Challenges and Areas for Reform

Curriculum

While the federal government does have common-core standards with the benchmarks students need to meet in literacy, it does not provide a curriculum on how children learn to read. While federal legislation, from No Child Left Behind to the Every Student Succeeds Act, includes language calling for “scientifically based” or “evidence-based” programs to teach reading, these terms are subjective, and curricula have changed over time.

In the last decade, the United States has undergone a shift in determining what constitutes “scientifically based.” In 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, EdWeek surveyed the most popular literacy programs in the country and found that at the time, most of them did not have a phonics-based approach. One of the top programs was The Units of Study for Teaching Reading, developed by Lucy Calkins at Columbia University’s Teachers College in New York City, the largest graduate school of education in the country. According to Forbes, Calkins’ curriculum is among the most popular in the country.

In Calkins’ original curriculum, children stuck on a word would use an approach called “three-cueing,” which involved looking at pictures rather than decoding letters to help sound out words. The curriculum was premised on the idea that children were natural readers who would learn to read by learning to enjoy reading and becoming “lifelong readers.” In 2022, following extensive research on the science of reading, Calkins retreated from her premise and in a major change, her new curriculum includes lessons on phonics and decoding for the first time. However, as of July 2022, her publisher delayed publication over some states’ concerns about how the new book mentions race, gender, and other forms of identity.

Several states have enacted their own versions of “science of reading” laws that mandate teaching phonics. As of July 2022, 30 states, across all regions in the United States, had either passed full science of reading laws or implemented policies related to them; 19 of these states initiated legislation since 2020.

Alongside these changes, several textbook publishers have changed how they teach reading, with a greater focus on phonics. A 2020 National Council on Teacher Quality report found that 51% of the schools in their study teach children to read through phonics-based programs, up from 35% in 2013.

Learning Differences

Dyslexia, a brain-based condition that impairs the ability to read, affects 20% of the population, making it the most common learning disability in the United States. The Department of Education helps fund the National Center on Improving Literacy, which aims to increase screening, identifying, and teaching students with literacy-related disabilities, such as dyslexia.

Children and adults with dyslexia can learn to read, but that often requires specialized education. Dyslexia is difficult to diagnose, with studies showing many cases of dyslexia are misdiagnosed or missed altogether. Children with dyslexia may not receive proper support without proper screening, leading to difficulties in school and increased dropout rates. In the United States, the national dropout rate for students with learning disabilities was 24% in 2020, compared with 5.3% of all students. In a famous case, the physicist Albert Einstein, who was dyslexic, struggled in school to the point that an elementary teacher said: “nothing good would come of him.” Einstein only succeeded when he changed to a school that took a more visual approach to education.

In 2015, the Obama administration issued a “Dear Colleague” letter stating that dyslexia, dyscalculia (affecting mathematical computations), and dysgraphia (affecting writing skills) were specifically covered under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). The letter states that students with these learning disabilities are entitled to additional support and intervention through Individualized Education Programs (IEPs). However, school districts still determine the specialized-education services in their districts, and some may not have the services a child needs.

ESAs are another way families can access specialized education for students by receiving funds to cover tuition at schools that meet individual needs.

Addressing Systemic Barriers to Literacy Access and Greater Literacy Equity

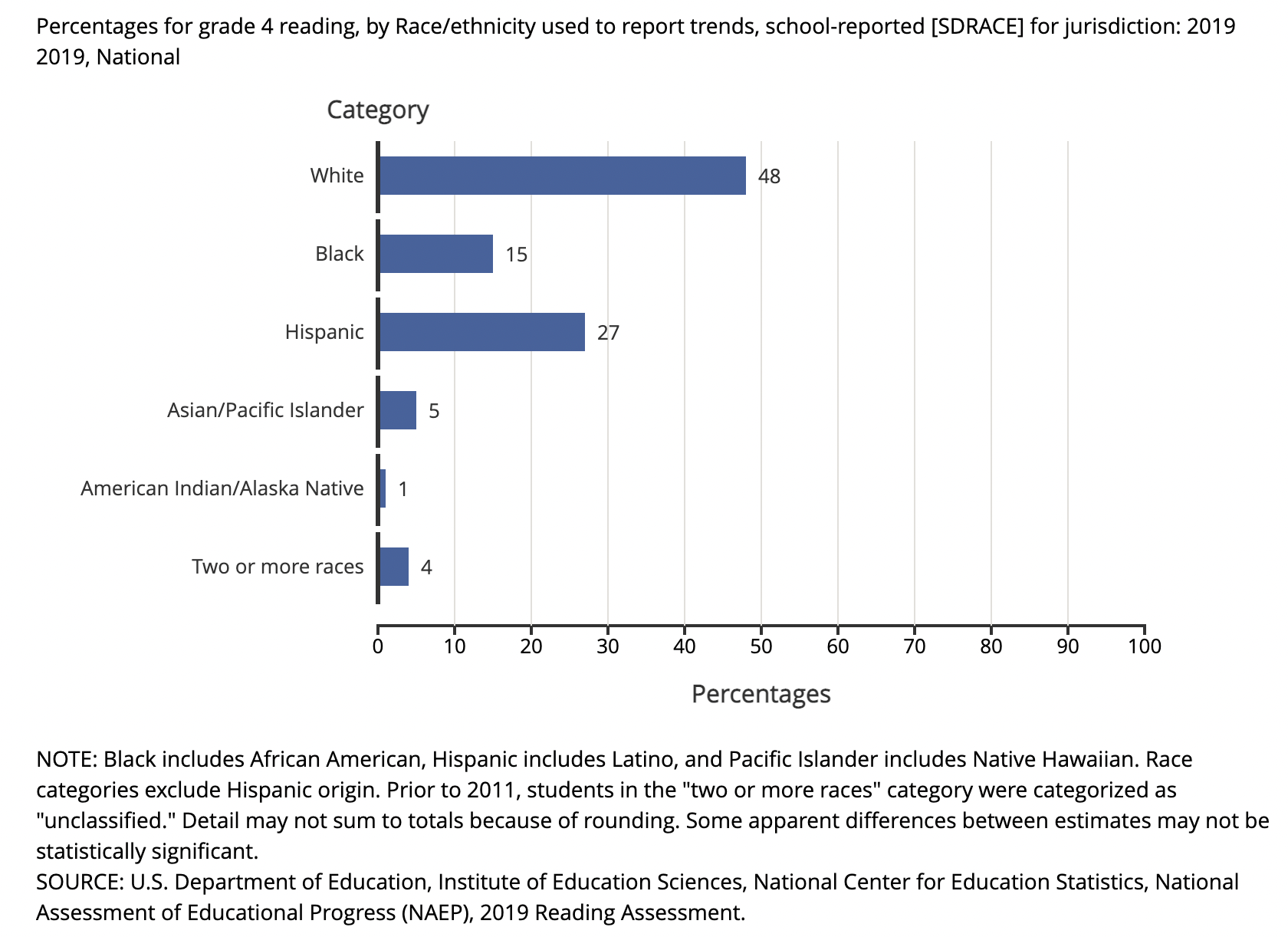

Since No Child Left Behind, state testing is broken down by race, ethnicity, and income status. The results show gaps in reading levels between White, Black and Hispanic students and along socioeconomic lines. The 2019 Nation’s Report Card showed that 55% of White fourth graders were not reading at grade level, compared with 72% of Black fourth graders and 67% of Hispanic fourth graders.

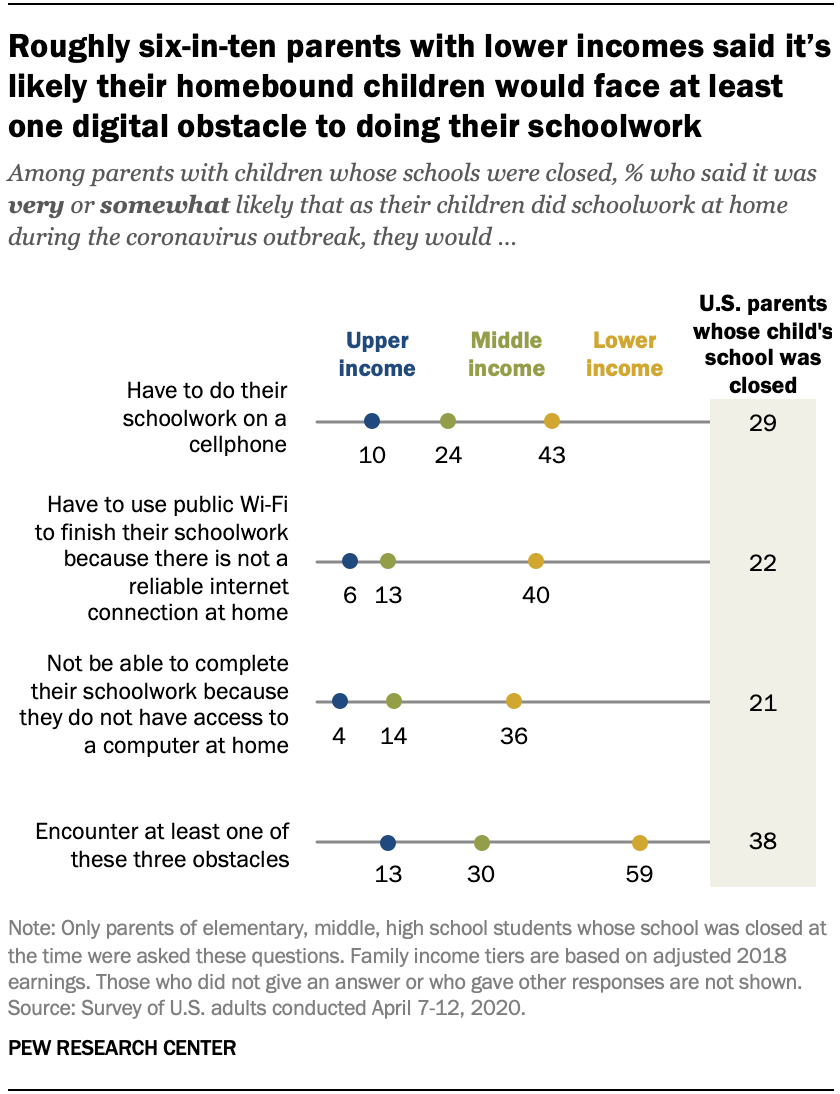

There were similar discrepancies in comparing the economic impact of literacy among students; the data shows that 79% of students who are eligible for “free and reduced lunch” (a term the government uses as a proxy to measure student poverty) were not reading at grade level, compared with 49% of students who did not qualify for for “free and reduced lunch.” Multiple studies have shown that these gaps widened during the COVID-19 pandemic and related learning loss that occurred from a stop to in-person learning. Given that most schools turned to remote learning when physical buildings closed, those with access to high-speed internet and/or an adult at home who was able to guide lessons had an advantage over those who did not.

There are many approaches to trying to reduce these gaps. In November 2021, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) provided:

- $14.2 billion for the Affordable Connectivity Program, which provides eligible households with discounts on broadband services.

- Over $7 billion to schools and libraries to provide broadband access through the Emergency Connectivity Fund.

According to an open-data database maintained by the fund, the government ultimately allocated fewer funds than it budgeted for.

Private companies have also tried to increase connectivity in rural areas, including a partnership with the SpaceX Starlink Internet Program and the Ector County school district in Texas, where nearly 40% of families did not have internet access in the 2019-20 school year. Another approach to closing the racial and socioeconomic gaps in reading looks at how zip codes impact access to education. Because many school districts receive funding from local property taxes supplemented by parent associations, there is a wide variance among richer and poorer neighborhoods, with students in wealthier areas receiving more resources. The federal government has tried to reach students in need through Title I funding, but there are several other approaches as well.

According to EdBuild, a nonprofit group working on school funding, 969 school districts in the country have “divisive borders” that keep schools divided by the race and income levels of their families. It argues for redrawing school-zone lines to increase economic and racial diversity. But critics argue that rezoning laws can perpetuate new boundaries that “exclude families of color.”

Another approach is to increase access to school choice through vouchers or ESAs, which give families funds to use for educational expenses, such as private-school tuition and tutoring.

In July 2022, Arizona’s governor signed legislation making all school-age children in the state eligible for Education Savings Accounts. Under the law, families that opt out of public and charter schools can receive $6,500 a year per child for education, including private school, homeschooling or tutoring. In August 2022, Senator Tim Scott (R-SC) proposed the Raising Expectations with Child Opportunity Vouchers for Educational Recovery (RECOVER) Act to give parents unspent education funds from the American Rescue Plan to use towards tutoring, private-school tuition, books, testing fees, and specialized services for children with disabilities.

Another approach is to increase the number of charter schools, defined as publicly funded independent schools established by teachers, parents, or community groups under the terms of a charter with a local or national authority. Unlike most public schools, charter schools do not have geographic boundaries that enroll students based on where they live and are not required to follow the guidelines of local school boards.

Nationally, charter schools have more support among Blacks and Hispanics across both major political parties. School choice through extending access to charter schools has advocates and critics. Advocates argue that charter schools can help address the disparities entrenched in the public school system by giving families more choice in where to send their children

Critics argue that charter schools may give federal funds to private companies to open schools and take money away from traditional public school systems thereby indirectly exacerbating existing inequalities among students in traditional public schools. For this reason, the Biden administration tightened regulations for operating charters in 2022; previously, every administration, from Bill Clinton to Donald Trump, had supported legislation for increasing access to charter schools.

In the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, enrollment in public schools fell by 3.3%. At the same time, charter school enrollment rose by 7%, the number of homeschooled children doubled to 10% and 35% of private schools reported an increase in enrollment.

Others argue that it’s impossible to generalize charter schools because they vary widely by location, funding, and management organizations. According to the most recent data from the 2019 Nation’s Report Card, over 65% of fourth graders across both charter schools and public schools were not reading at grade level. Likewise, a Department of Education study using data from the 2019 Nation’s Report Card found there was “no measurable difference” in average reading or math scores among fourth-grade and eighth-grade students in traditional public and public charter schools.

Conclusion

Though adult literacy is correlated to higher employment rates, greater trust in institutions and better health outcomes, over 50% of American adults read at or below a sixth-grade level. While there are programs that focus on increasing adult literacy, investment in reading skills during early-childhood programs produces more effective long-term results.

The majority of fourth graders in the United States were not meeting reading benchmarks in 2019, and most states reported decreases in reading levels between 2017 and 2019. Early studies show that the pandemic has exacerbated these trends, with widening gaps indicating that the most at-risk students are falling further behind their peers. The federal government has tried a wide range of solutions, from increasing Title I funding to creating a National Report Card to enforcing common core-curriculum standards. Most recently, the government poured $190 billion into schools as part of the relief efforts under the Trump and Biden administrations. In the meantime, some administrations and legislators have looked to improve access to school choice through vouchers, Education Savings Accounts, and charter schools. Ultimately, the country will need to find a path forward so that more children learn to read and in turn, become more literate, successful adults.

Ways To Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Learn about the literacy rates in your state and school district.

- Use the Nation’s Report Card to see what percentage of fourth-grade students are reading at grade level in your state and in your district. Are these rates above or below the national average? What discrepancies do you notice across different areas?

- Use a skills map from the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) to see your district’s adult literacy rates.

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? What are they doing to improve literacy? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them. These people include elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Ask your local school-board member how your district is addressing literacy rates.

- Is there a community-based initiative or task force addressing adult literacy in your neighborhood?

- Find out if your senators or representatives are members of the committees that address literacy in your state.

- What commissions address literacy in your state?

- Use the National Literacy Directory to see if there are nonprofit organizations in your area addressing literacy that you could be involved with.

- Are you aligned with its mission statement?

- What is the organization’s budget?

- How is the organization funded?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with faith-based organizations, community organizations, school boards, and local businesses.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team at communications@thepolicycircle.org, for connections to the broader network, advice, and insights on how to build rapport with policymakers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Consider participating in The Policy Circle’s Civic Leadership Engagement Roadmap (CLER). CLER 3.0 focuses on education

- Find out what your district is doing to reach the children in your community who are not meeting reading benchmarks.

- Work with local politicians and organizations to find solutions.

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.

Key Sources

- The Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy is dedicated to expanding access to literacy services for adults nationwide because of the transformative power of literacy. They believe that literacy not only provides dignity to every person, but provides the opportunity for exploring ones fullest potential.

- The National Center for Education Statistics is the primary federal entity for collecting and analyzing education data in the United States. It fulfills a Congressional mandate to collect, analyze and report statistics on the condition of American education.

- The National Conference of State Legislatures maintains a database for tracking education legislation

- The National Literacy Directory includes a database of literacy programs throughout the country.

- The Nation’s Report Card, part of the National Assessment of Educational Progress, includes national data from assessments in subjects such as mathematics, reading, science, and writing.

- The Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies-PIAAC is also known as the Survey of Adult Skills. It is an international study of key cognitive and workplace skills of adults ages 16-65. Related references to the PIAAC study include the following:

-

- The OECD’s country note on the United States

- The PIAAC Prison Study, published in 2016, includes data from US prisons in 2014.

- The PIAAC Skills Map, which includes breakdowns from the PIAAC study by state and county

-

- The Programme for International Student Assessment-PISA– is an international exam administered by the OECD

- Proliteracy is the largest adult literacy and basic education membership organization in the country.

-

- The State of Global Learning Poverty: 2022 Update report was published by the World Bank, UNESCO, UNICEF, USAID, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office.

- The United States Census Bureau publishes data about the people and economy of the United States.

- The United States Department of Education is a cabinet-level agency. The following key sources are within the department:

-

-

- A database of appropriations for federal programs

- The World Literacy Foundation– is a global nonprofit organization focused on literacy.

-

- Literacy First is a non-profit organization that partners with school districts in Central Texas to ensure all children are reading at or above grade level by third grade.

- Brink Literacy Project is a global nonprofit organization that uses storytelling to promote literacy and personal development.

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.