Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

“Government regulations” may sound like a complicated concept that is hard to grasp and even harder to influence. This Policy Circle brief provides an overview of the regulatory process, its purpose and origination, and how regulations provide the foundation for a free market to create an economic environment for civil society to flourish.

This Policy Circle brief will explain the process of creating and implementing regulations, explore examples of how government regulation influences your daily life, and finally, how you can make an impact.

Whether you want to open a restaurant featuring your grandma’s Italian pasta, take your business national, or teach at the local school, you are affected by local, state, and federal regulations.

Case Study

A Department of Energy (DOE) rule published in early January 2001 increased the energy efficiency of residential clothes washing machines. The Heritage Foundation reported the regulation increased the price of new appliances, and consumers would spend less on energy and water bills. However, Mercatus Center calculates the net cost for households increased unless the washing machine was used at least 300 times per year (5.8 times per week), well above the 282 average. Additionally, consumers and product reviewers encountered issues, like mold, in newly popular front-load machines that met the new efficiency standards.

Why washing machines? Because washers are a common household appliance that we may not consider steeped in government regulations. Manufacturers must comply with the regulatory standards yet still meet the needs of consumers.

After research in the sunshine state discovered the correlation between vehicle emission levels and air pollution in the 1950s, the state enacted environmental and emissions regulations to reduce pollution levels. The respective state agency was founded in 1967 by then-California Governor Ronald Reagan.

Following suit, the Nixon administration created the Environmental Protection Agency and passed federal laws in the 1970s to reduce automobile emissions. California was, and is still today, the only state authorized to set its own regulations. Other states may implement standards similar to California since its regulations are stronger than the federal standard but are not authorized to establish their own. By 2035, California will require all vehicles sold in the state to be electric, hydrogen-fueled, or plug-in hybrid.

Regulations affect the everyday lives of Americans in inconspicuous and also obvious ways. Regulations may seem, at the outset, to diminish choice or freedom, like which vehicle you can purchase in California after 2035; yet one overarching purpose of regulations is to ensure the longevity of civil society.

Why it Matters

Generally, regulations create a standard of ground floor conditions to implement laws for any given area of industry or public service. Alternatively and simultaneously, regulations may impede the entrepreneurial ability to introduce innovations and freely operate in the industry or market in question.

Since regulations have the power to impact innovation, business, and the delivery of services, policymakers tasked with creating regulations must balance the safety and security of societal and government infrastructure with the public interest, along with fostering creativity and innovation in a free market.

In recent years, the popularity of the “sharing economy” sparked debate over how to regulate services such as Uber and Airbnb. Ridesharing and renting temporary living spaces is nothing new. Taxi cab companies and hotels, both federally regulated, might not appreciate the competition, but consumers want more choices than what has always been.

Private citizens use their own vehicles and homes to make money and provide a service to the consumer. How does the government regulate the sharing economy? How quickly can governments respond to innovation?

Wharton’s Professor Sarah Light explores this topic in her paper: “The Role of the Federal Government in Regulating the Sharing Economy,” which discusses how business intersects with the law and regulations and explores how innovation spurs regulatory change. Light purports that experimenting on a small scale to see what regulations work is the best way to navigate the intersection of innovation and regulation.

Introducing a new way to access an established industry is good for the consumer, drives competition, and inspires innovation.

Innovative ventures face many challenges, such as adjusting to rapid growth, finding talent, and competing in a fast-paced and diverse economy. When you pile on burdensome regulations that are broadly applied, the chance for success dwindles. According to the Small Business Association, only about half of startups remain in operation after five years.

Putting it in Context

History

The process of developing regulations, or rulemaking, is an indispensable aspect of American civil society. According to the Federal Register’s Guide to the Rulemaking Process, “[a]n agency must not take action that goes beyond its statutory authority or violates the Constitution.” This limited authority prevents agency overreach.

Industries like energy and consumer manufacturing are highly regulated because the federal government provides oversight of industries that have high interactions with the populace. The balance between the oversight to protect citizens while fostering industry growth remains an area of debate.

Opponents speculate constant introduction of regulations is unnecessary oversight that diminishes fresh ideas and causes frustrating and unnecessary burdens on individuals and businesses while doing little to protect interests. Proponents of regulations consider they support citizens’ safety and well-being and foster a healthy marketplace.

Federal regulations are “a set of requirements issued by a federal government agency to implement laws passed by Congress.” Rulemaking is the procedural process that executive branch agencies use to issue new federal, state, or local regulations. The process is meant to be informative and transparent and can take anywhere from several months to several years.

For federal regulations, the rulemaking process includes:

- A federal agency evaluates possible rules to implement a federal law

- The agency provides a forum for the public and interested parties to review the proposed rules for a period of time

- The agency proposes the final rule.

This rulemaking process remains the same when the agency considers removing an existing regulation. The federal rulemaking process is governed by the Administrative Procedure Act (APA):

“The core pieces of the act establish how federal administrative agencies make rules and how they adjudicate administrative litigation…clarifies that rulemaking is the ‘agency process for formulating, amending, and repealing a rule,’ and adjudication is the final disposition of an agency matter other than rulemaking.”

In addition to passing laws that require regulations that spur the rulemaking process, Congress provides oversight of an agency’s actions and process. The Office of Management and Budget’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) reviews proposed rules and conducts a cost-benefit analysis to determine if the benefit of the proposed regulation outweighs the cost to implement.

One of The Policy Circle’s core values is civic engagement. The onset of the internet and digital rule proposal means the public has greater access to participate in the rulemaking process on the federal level. To learn more about your state’s regulatory process, check out this guide by the Library of Congress.

By the Numbers

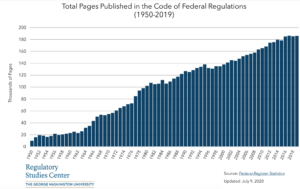

The Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) codifies the general and permanent rules published by the executive departments and federal agencies in the Federal Register. The first CFR was published in 1938 and includes 50 broad subject areas, from Banks to Agriculture to Highways.

Here’s the growth in the last 60 years:

- In 1960, it was 22,877 pages

- In 1975, it was 71,224 pages

- In 2000, it was 138,049 pages

- In 2019, it was 185,984 pages.

The situation is similar at the state level. It would take over 23,000 hours, or 11.5 years, of reading to get through state regulations. See your state’s regulatory rankings in CATO Institute’s Freedom in the 50 States Index.

The Role of Government

Regulation occurs at the federal, state, and local levels. When the government sets a new standard, or ‘policy criteria,’ an agency proposes regulations that agencies, states, regulatory bodies, individuals, businesses, etc. must follow. Examples of local regulations include zoning ordinances, rent controls, and restrictions on the sale of mixed drinks at restaurants. Examples of state regulations include legal drinking ages, speed limits on state highways, and occupational licensing.

Federal Level

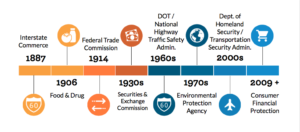

In some cases, it is more efficient to have one federal agency than it is to have 50 state agencies. Regulatory compliance costs tend to be lower when firms face the same regulations in all 50 states instead of complying with multiple regulations across state lines.

The following is a broad timeline of agencies and when they were created:

Federal regulatory agencies include the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The FDA is a federal regulatory agency tasked with maintaining food and drug quality in the United States. According to the agency’s website, it carries out its mandate through the “development of performance characteristics, testing methodology, manufacturing practices, product standards, scientific protocols, compliance criteria, ingredient specifications, labeling, or other technical or policy criteria.”

When a regulation aims to achieve a goal – such as reducing environmental impact – it has unintended results like higher costs or a reduction of performance, as is with regulations on washing machines.

An Example:

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is one of the many federal regulatory agencies. According to the EPA, “Congress passes the laws that govern the United States, but Congress has also authorized EPA and other federal agencies to help put those laws into effect by creating and enforcing regulations.” For an extensive list of federal agencies, see USA.gov.

Even when a law passes, it often does not include details on how state and local governments should implement the law or how individuals and businesses should follow the law. Congress authorizes government agencies, such as the EPA, to create regulations that set specific guidelines and requirements.

For example, the Clean Air Act regulates air emissions but does not give specifics. Instead, the law authorizes the EPA to establish standards that explain what levels of what type of pollutants can be legally emitted into the air and what the penalty will be if those levels are exceeded.

Individuals can view and comment on rules by visiting Regulations.gov. As stated earlier, technology significantly increases the public’s participation in this process, so the agency has more information to review than just from interested parties.

Congressional Review Act (CRA)

The Congressional Review Act was adopted in 1996 to give Congress more oversight of executive agency regulations. The Act enables Congress to overturn a final rule issued by a federal agency. The agency is prevented from reissuing a similar rule in the future unless authorized to by Congress.

Role of the Private Sector

Historically, the private sector helps to drive innovation, but it cannot sidestep government regulations to operate. Innovation may present challenges to current industry regulations meant to ensure the public interest and public confidence.

Quite recently, Congress passed three major bills “which aim to improve America’s infrastructure, boost competitiveness with China, and accelerate new climate technologies,” the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), CHIPS Act, and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). As outlined in this brief, now begins the regulatory process.

Though these pieces of legislation promise to accomplish significant policy efforts for the U.S.’s economic stability, growth, and sustainability, agencies must work quickly through the rulemaking process. The private sector has the potential to continuously and creatively contribute to these efforts, foster innovation, and improve regulatory efficiency.

Current Challenges and Areas for Reform

Regulations must balance the need to keep individuals and the environment safe while minimizing any negative impact on entrepreneurial activity or disproportionate cost to the consumer, which is the engine for economic growth and employment.

Broad Efforts at Reform

Founding Father James Madison made a case for a less complicated system of rules and regulations:

“It will be of little avail to the people, that the laws are made by men of their own choice, if the laws be so voluminous that they cannot be read, or so incoherent that they cannot be understood: if they be repealed or revised before they are promulgated, or undergo such incessant changes, that no man who knows what the law is today can guess what it will be tomorrow. “

Given how long it would take any person to read and understand hundreds of thousands of pages of regulations that implement our laws, strategies for reform are continuously discussed. Arguably, the most important purpose of government regulation of many industries and services is for public benefit. However, if many average Americans were surveyed on the topic of regulations, their understanding of the nuances surrounding regulations would most likely be limited.

National Affairs contributor James Broughel explains that regulatory bodies and the regulations they propose have evolved to benefit special interest groups within any given industry because of their influence on the rulemaking process, which negates their intended purpose. This phenomenon is a theory known as “regulatory capture.” On the other hand, Broughel surmises that “public interest” holds two perspectives: one, that regulators genuinely have the agency mission and the people they serve at heart when they propose regulations at that time; and two, from a purely economic perspective, that regulations serve to correct market failures.

Broughel suggests a new phase of regulatory reform should include both – an overarching reform theory that includes both economic stability and growth coupled with public interests. He goes on to spur “free-market thinkers” into playing a more influential role in the rulemaking process and to do a better job at communicating their public interest to the public at large.

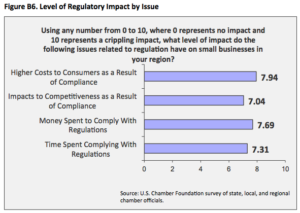

Costs

Implementing regulations come with a price tag. For example, businesses sometimes need to hire specialists familiar with new, relevant regulations to conduct adequate tracking and reporting, increasing the costs, which transfer to the consumer.

By one estimate, compliance costs for manufacturers rose 7.6% each year between 1998 and 2012. Since the 2008 Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, regulatory costs have increased, which puts a palpable strain on business owners.

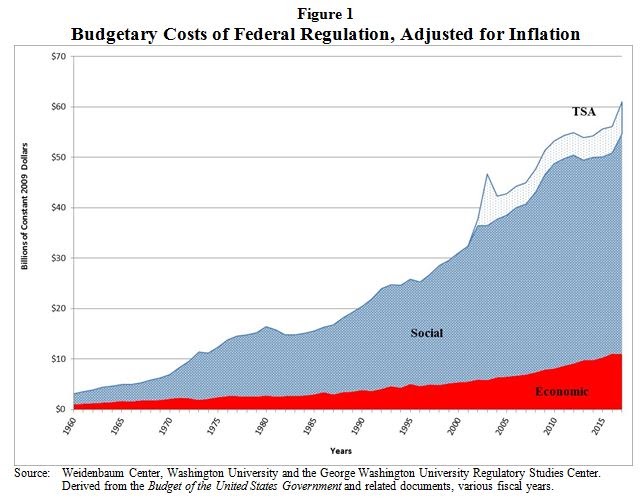

The U.S. Treasury collected approximately $1.4 trillion in individual income taxes in 2014, meaning “the annual costs of regulations may be roughly as consequential as what the public pays in income taxes.” Tracking the cost of regulations, however, is not straightforward. This table outlines federal agencies’ budgetary growth in hiring regulatory staff.

Measuring the cost of regulations is difficult to capture and is no longer thoroughly studied, according to Broughel. Economists and regulators have moved away from developing regulations with the cost in mind; yet regulators in the industry are the ones influencing the rulemaking procedure, and some move in their own self-interest to prevent further regulatory costs, which also inhibits the influx of new ideas.

Regulatory Buildup

According to the Mercatus Center at George Mason University’s paper on Regulatory Accumulation and Its Costs, policymakers “pay little attention to how the buildup of regulations over time has hindered innovation and damaged economic growth.” Since 1997, total regulatory restrictions have increased by almost 20% to over 1 million.

During the Clinton Administration, the average annual number of significant regulations with an economic impact of over $100 million was 36. During the Bush Administration, it increased to 45, and again to 72 during the Obama Administration. A 2020 estimate from Mercatus scholars says regulations dampened economic growth by 0.8% annually between 1980 and 2012.

Mercatus estimates these losses in economic growth amount to income losses of a cumulative $13,000 per American. Still, final costs can be as much as six to eight times a share of income for low-income households than for high-income households since regulatory accumulation is often associated with higher prices.

Many regulatory agencies rely on third parties to track, manage, and analyze regulatory activity. Multiple service providers for different agencies lead to redundancy, mismanagement, and fragmented systems that add to the regulatory buildup. Esper is a regulatory technology company “pioneering a new platform to manage the end-to-end rulemaking processes in government agencies.” Implementing technology that cross-checks regulations via a searchable database to show intersecting or overlapping regulations can help ease regulatory accumulation and its associated costs.

Occupational Licensing

According to the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL), occupational licensing requires “workers to submit verification of training, testing, and education – and often pay associated fees – before beginning a job in their chosen field.” Improper training can cause harm to the public, like in the medical field, so a standard of licensure increases public safety. Additionally, individuals who aim to work in a field must demonstrate their commitment to legally work in the field by fulfilling prerequisites and legal requirements to do so.

Opponents argue that licensing creates barriers to employment, and “licensing burdens often bear little relationship to public health or safety.”

For example, a public interest firm’s report, Institute for Justice, found a cosmetologist needs 11 times more training than an emergency medical technician. This is just one of the 25% of all jobs that requires an occupational license today. Sixty years ago, only 5% of jobs required a license.

Licensing is a requirement at local, state, and national levels for certain occupations. Truck drivers and cosmetologists, for example, typically have state-issued licenses. Some workers, such as taxi drivers, may be licensed by their city. Workers in a few occupations, such as airplane pilots, must obtain a federal license because airspace is regulated by the Federal Aviation Administration.

One way to help ease the burden on individuals is through licensing reciprocity. Licensing reciprocity is the concept of developing “common frameworks for how states recognize licenses from other states” and includes mutual recognition or acceptance of licenses granted by other jurisdictions; similar to how a driver licensed by Arkansas is lawfully allowed to operate a motor vehicle in California. Interstate licensure acceptance is established by comparable standards.

For example, Arizona’s Universal Occupational Licensing bill, enacted in April 2019, sets guidelines for recognizing licenses from out of state. For more on Arizona’s legislation, listen to this podcast from the Federalist Society’s Regulatory Project for more on Arizona’s legislation.

In the medical field, the Nurse Licensure Compact “allows nurses to practice in states that participate in the compact without undergoing additional licensing requirements,” and has been crucial during the coronavirus pandemic, even prompting states not part of the compact to issue emergency licensing waivers to support overwhelmed hospital systems.

You can read about your state license and permit requirements here. For a few state comparisons, like those pictured below, see this analysis of your state in the Institute for Justice’s report, this Mercatus report, this National Occupational Licensing Database produced by NCSL, The National Governors Association for Best Practices, and The Council of State Governments.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Impact on Small Business

Regulations are often “promulgated without regard for the unintended consequences, particularly for small businesses.” A Mercatus study found “that as complication in regulation grew, there was a decline…in the number of small firms; the increase in complication of regulation did not affect large firms” except for an association with a decrease in hiring among all firms.

Entrepreneurs and small businesses are often subject to four levels of regulation: federal, state, county, and city. These include licenses, permits, and certificates. These regulations can overlap and conflict, which makes compliance confusing and costly.

The National Federal of Independent Businesses (NFIB) 2020 Problems and Priorities report, “Unreasonable Government Regulations,” “Uncertainty over Government Actions,” “State/Local Paperwork,” and “Federal Paperwork” all rank in the top fifteen most essential problems facing small businesses (out of seventy-five total potential challenges). As of September 2022, NFIB reports small businesses expect increased improvement, but are still recovering from the pandemic and are burdened by inflation.

The Regulatory Flexibility Act, and subsequent amendments, consider the effects of regulations on small businesses and organizations, but regulations still pose problems for small businesses and prospective entrants. A further step proposed is to exempt small businesses from certain regulations if they are not a source of the problem the regulation seeks to solve.

Government Restraint

The more a society’s resources are allocated by the government, the less the market can direct to their most productive uses. Excessive government regulation stifles growth and should be limited (see The Policy Circle’s Economic Growth Brief for more.)

The Trump Administration introduced a rule that for every one new regulation, two regulations had to be repealed. Halfway through 2019, the Competitive Enterprise Institute reported just over 1,000 rules and regulations had been issued; for context, the annual count has not been below 3,000 since the 1970s. For more, see the Office of Management and Budget’s Unified Agenda of Regulatory and Deregulatory Actions.

Regulations Abroad

How do U.S. regulations compare to those of other countries? The Netherlands, Canada, Australia, and the UK have all adopted legislation that requires the government to offset the costs of new regulations. The Netherlands adopted a “net quantitative burden reduction target” to reduce regulatory burdens by tying new regulations to revisions of existing regulations. Canada’s 2012 One-for-One rule is similar to an Australian policy that says reductions in existing regulatory burdens must fully offset the cost burden of one new regulation. The UK went one step further: its “One-in, One-out” rule became “One-in, Two-out” in 2013 and “One-in, Three-out,” in 2016.

In recent years, European policymakers have started to ease regulations to “champion entrepreneurship that can kick-start much-needed economic growth.” Still, “costs and hassle” facing new companies, startups, and entrepreneurs are a constant reality.

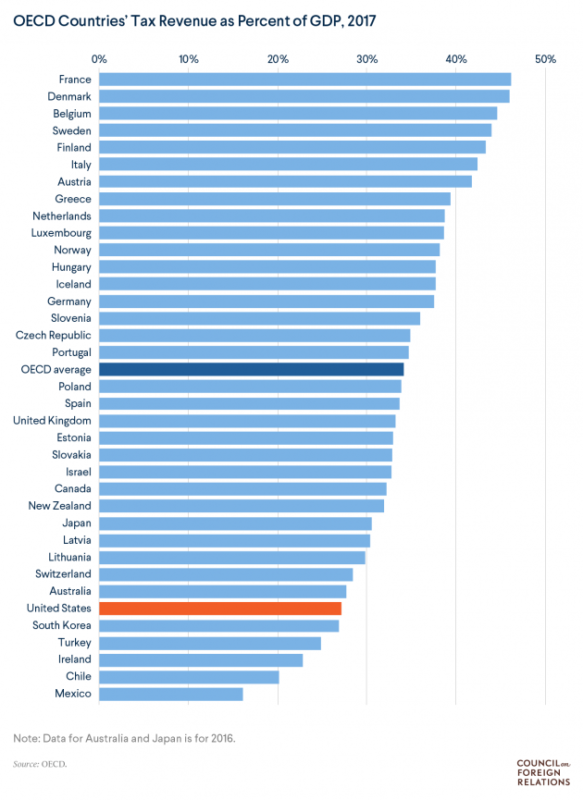

Unlike in the United States, where entrepreneurs “have used stock options for employees to spur innovation,” many entrepreneurs in the EU are stifled by the need to “navigate onerous tax rates and restrictions.” Almost half (49%) of venture capitalists and founders say European regulations make them hesitant to invest. This makes it more difficult for startups to generate a profit and spur economic growth. It speaks to a larger debate in economics that focuses on the role of regulation in the economy and its impacts on economic growth. Take a look at the graph comparing different countries’ tax revenues.

Conclusion

Economists and institutions provide grants that invest in innovative ideas with the potential to transform society for the better. The balance between order, standards, and safety with economic prosperity and innovation is, and continues to be, a challenge for our federal and state governments.

There is a fine line between regulations that benefit society and keep individuals and the environment safe and regulations that inhibit entrepreneurship, economic growth, and employment opportunities. Understanding the costs and consequences of imposed regulations, and exercising restraint to prevent such adverse effects, are key to local, state, and national environments that allow individual creativity to thrive.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Find out what your state and district are doing about rules and regulations.

- Do you know how your state ranks in the number of regulations?

- What are your state’s occupational licensing laws?

- Is there a task force related to regulatory reform, or does one need to be formed?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- What steps have your state’s or community’s elected and appointed officials taken?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is an excellent opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Find allies in your community or nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with community organizations and local businesses.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team at communications@thepolicycircle.org for connections to the broader network, advice, and insights on how to build rapport with policymakers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Submit public comments on regulations at regulations.gov.

- Research the regulations impacting your life. Many regulations have unintended consequences and require an informed public to shine a spotlight on them.

- Look at the National Council of State Legislature’s Occupational Licensing Database or the Small Business Association’s licenses and permits to learn about your state’s rules and regulations.

- Reach out to local business owners and entrepreneurs to learn what regulations they must comply with.

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.

Thought Leaders/Additional Resources

The Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. The OIRA administrator is often referred to as the “regulatory czar.”

Jeff Rosen: Putting Regulations on a Budget, National Review

Susan Dudley: Director of the George Washington University Regulatory Studies Center

Additional Resources

- “Over Regulated America,” The Economist

- List of Most (to least) Regulated States, Mercatus Center

- George Washington University’s Regulatory Studies Center

- The Federalist Society’s Regulatory Transparency Project

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.

Deep Dives

Want to dive deeper on Government Regulation? Consider exploring the following: