Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this Brief.

Listen to the Trust Your Voice Podcast for an audio version of this Brief:

Case Study

J.J. McCorvey of the Wall Street Journal recognized his mother was recently widowed, living without a second household income, and “approaching the reality of living on Social Security.” But when he asked himself what his mother’s savings looked like, he confessed he had no clue. “Like so many people of my generation,” he writes, “I had never talked in-depth to my parents about their finances.”

Growing up, McCorvey explains his parents insulated him and his brother “from the worrisome and complicated world of credit cards, mortgage payments and consolidation loans.” This lack of communication compounds itself over time, leaving generation after generation without financial acumen. Had he known about his mother’s withdrawal from a 401(k) plan, for example, he says he likely would not have cashed out on his own 401(k) and would have instead rolled his funds into an IRA.

Luckily, it only takes a few steps to change direction. Instead of living in the moment or paycheck to paycheck, “focusing more on simply surviving financially than living,” McCorvey has taken it upon himself to “get us better at living for the future.” He has investigated and educated himself on 401(k)s. He discusses financial literacy and shares articles and podcasts with his friends. He has even opened savings accounts for both him and his mother.

“Now, if we don’t, in turn, have some of those conversations with our parents, we miss out on this incredible opportunity to pay them back for raising us the best they could with the resources at their disposal.” They’ll learn together, because it’s never too late to start.

Why it Matters

Financial literacy is defined as “‘the ability to use knowledge and skills to manage one’s financial resources effectively for lifetime financial security’.” Financial literacy is more than knowing financial facts; it is also understanding and applying this financial knowledge to the parts of our lives that depend on sound financial management: managing monthly bills, budgets, credit cards, and loans; having a savings plan for the future; deciding where to live and buying a first home; getting married and providing for a family; or starting a business and planning for retirement.

Financial literacy is defined as “‘the ability to use knowledge and skills to manage one’s financial resources effectively for lifetime financial security’.” Financial literacy is more than knowing financial facts; it is also understanding and applying this financial knowledge to the parts of our lives that depend on sound financial management: managing monthly bills, budgets, credit cards, and loans; having a savings plan for the future; deciding where to live and buying a first home; getting married and providing for a family; or starting a business and planning for retirement.

Without a stable foundation of money management skills and an understanding of financial issues, individuals are less able to optimize their welfare and are more vulnerable to making questionable investments or to exploitations. This can have even larger repercussions on a state and national level, as it can lead to higher social safety net usage, inability to achieve independence, and overall lower quality of life for society, communities, and families. And if we as citizens are not financially responsible, how can we hold our elected officials accountable to manage public finances?

Start by familiarizing yourself with this glossary of financial terms, or test your knowledge with the financial literacy quiz by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA).

Learn the essentials to better understanding and managing your finances from industry experts Lorraine Gavican-Kerr, Indiana State Treasurer Kelly Mitchell, and Scott Niederjohn in The Policy Circle’s Move the Needle Virtual Experience: Achieving Financial Freedom:

Putting It Into Context

What is Financial Literacy?

Financial literacy encompasses knowledge of financial products as well as basic numeracy and budgeting skills. To an even greater extent, financial literacy is about understanding finances and economics so individuals can make the best financial choices to pursue their goals. This means not only understanding interest rates, different kinds of mortgages, and why credit scores matter, but also knowing how to take action and apply this knowledge to financial decisions throughout life.

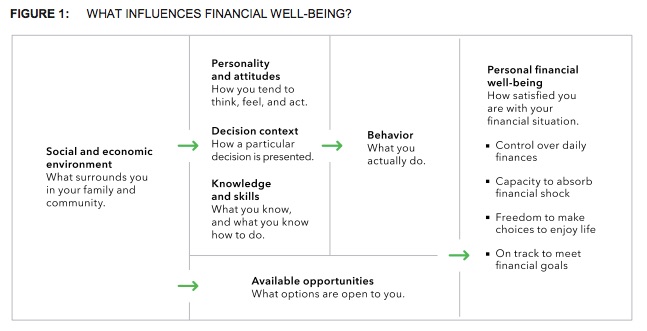

Beyond any financial facts, turning knowledge into action is what truly enables financial well-being, explained by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau as “a sense of both financial security and financial freedom, in the present moment and when considering one’s future.” This entails addressing all the pieces that influence and are affected by financial management, from individual income and budgetary priorities to accessing jobs and educational opportunities.

By the Numbers

Financial literacy among Americans has been steadily declining. According to the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) Foundation’s National Financial Capability Study, the rate of financial literacy for Americans fell from 42% to 34% between 2009 and 2018, despite the fact that over 70% of Americans self-report being highly financially literate. The latest results in the 2022 FINRA study, Investors in the United States: The Changing Landscape, “reveals a new generation of younger and less experienced investors that is vastly different from older generations in their investment behaviors and attitudes.”

Explore your knowledge and take the FINRA Financial Literacy Quiz.

Banked vs. Unbanked

According to a recent study by a U.S. banking regulator and reported by Reuters in 2022, “the share of Americans who did not have a checking or savings account fell last year to the lowest level since the financial crisis.” Roughly 4.5% of 132.5 million households within the United States were “unbanked” meaning they have checking or savings accounts but have used alternative financial services such as paying bills or cashing checks through a service other than a bank or credit union. In total, 66% of the American population is fully banked (has a checking or savings account and has not used an alternative financial service in the past year). Younger, low-income Americans are most likely to be underbanked or unbanked.

Debt

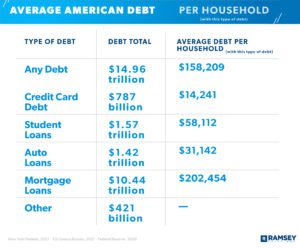

The National Financial Capability Study found that almost 80% of Americans have at least one of six types of debt, including credit card balances, mortgages, auto loans, student loans, unpaid medical bills, or non-bank loans such as those from the government or payday loans. Another 30% of Americans have three or more of these types of debt simultaneously.

These rates have remained fairly constant since 2012, but jumped slightly during the pandemic. According to Experian, the total U.S. consumer debt balance in 2020 grew $800 billion, a 6% increase over 2019 and the highest annual growth jump in over a decade. American household debt hit a record $14.6 trillion in spring of 2021, and was approaching $15 trillion in the fall of 2021. Heightened inflation throughout 2021 and 2022 has not helped this; according to the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey covering March-April 2022, there was a 32% increase in the number of people saying they were relying on credit cards and loans to meet their spending needs. Further, a recent 2022 study found that households “increased debt at the fastest pace in 15 years due to hefty increases in credit card usage and mortgage balances.”

Planning

Planning

According to the U.S. Federal Reserve’s Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households, only 36% of non-retired American adults believe their savings are on track for a secure retirement, and 26% of Americans have no retirement savings at all. Over half of the respondents in the National Financial Capability Study indicated they have not even tried to determine how much they would need to save for retirement.

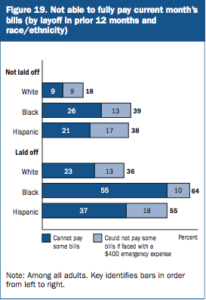

Long-term planning may be a burdensome endeavor, but Americans do not fare much better in the short-term. The Federal Reserve found more than 25% of American adults had one or more bills they were unable to pay in a given month, or were one $400 financial setback away from being unable to pay them. Only 49% of respondents to the National Financial Capability Study indicated they have 3 months’ worth of emergency funds – this is an improvement from the 35% in 2009, but still just barely half of the respondents.

Gender

A study by Charles Schwab found that parents are more likely to emphasize budgeting with their daughters and investing with their sons. This gender gap extends throughout life and greatly affects women’s financial confidence. Women are more likely than men to feel anxious about finances and only 31% of women with at least a bachelor’s degree were comfortable managing their investments. In fact, only 17% of American women between the ages of 60 to 75 passed a retirement income literacy survey from The American College of Financial Services. In the Federal Reserve’s report, which included 3 questions to test financial knowledge, women answered only about half of the questions correctly (52%, compared to men answering 65% correctly) and were more likely to select “don’t know” or skip the question (39%) compared to men (27%).

Of women age 65 and older in 2019, 14.4% of widows, 15.8% of divorced women, and 16.9% of never-married women had total incomes below the official poverty threshold, compared to 4.7% of married women.

Further, studies have demonstrated that by 2030, “roughly $30 trillion is slated to change hands in the U.S. Often referred to as “the great wealth transfer,” this exchange will happen as aging baby boomers pass on assets to the next generation, and women are set to inherit a large portion.”

This financial shift makes financial literacy even more important. As women take on more significant roles in the economy, understanding financial concepts becomes essential for making informed decisions about investments, savings, and overall wealth management.

Race

Black (41%) and Hispanic (38%) respondents to the National Financial Capability Study were more likely to report having trouble in covering unexpected expenses, compared to white respondents (27%). In the 2021 Personal Finance Index from the Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America and George Washington University, white participants answered 55% of the questions correctly, whereas Black participants answered 37% of questions correctly and Hispanic participants answered 41% of questions correctly. This gap “remains after controlling for other socio-economic factors such as gender, education, marital status, and household income.”

Students

Student loan debt is the second largest debt category, behind mortgage debt and higher than both credit card and auto loans. In the U.S., close to 45 million borrowers owe over $1.5 trillion in student loans. Across income levels, about 44% of National Financial Capability Study respondents (ages 18-34) have student loans they need to repay. Of those, 42% had been late with a payment at least once that year and 48% expressed concern about being unable to pay off their student loans. Older cohorts also face the stressors of debt; in fact, the Federal Student Loan Portfolio shows the 35-49 age group owes more than the 25-34 age group, demonstrating that repaying loans can be a burden that remains well into years when people are having children and buying homes.

The Role of Government

Federal Level

The Treasury Department’s mandate is “to maintain a strong economy by promoting the conditions that enable economic growth and stability at home and abroad.” However, the department also acknowledges that “federal agencies are not solely, or even predominantly, responsible for providing financial education to Americans.” Instead, it recommends the federal role in financial literacy education be “developing and implementing policy, encouraging research, and developing educational resources as needed,” rather than trying to reach every American directly.

The federal government’s role has mostly been through the “dissemination of financial education research, best practices, and resources for practitioners.” The 2020 U.S. National Strategy for Financial Literacy identifies five priority areas for federal activity, which are:

- Basic financial capability;

- Retirement savings and investor education;

- Housing;

- Post-secondary education; and

- Veterans

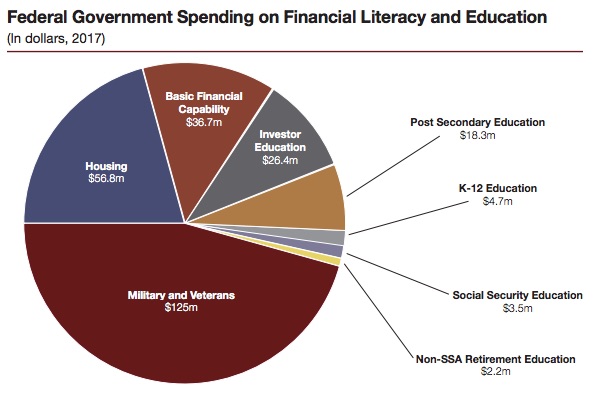

Annually, the federal government spends close to $300 million on financial literacy and education programs to educate Americans (as of early 2022, the graph from 2017 is the most recent available from Treasury reports). These activities span 23 federal agencies and entities, ranging from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s Money Smart program, to the National Credit Union Administration’s Financial Literacy & Education Resource Center, to the Financial Literacy and Education Commission’s My Money resources.

Annually, the federal government spends close to $300 million on financial literacy and education programs to educate Americans (as of early 2022, the graph from 2017 is the most recent available from Treasury reports). These activities span 23 federal agencies and entities, ranging from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s Money Smart program, to the National Credit Union Administration’s Financial Literacy & Education Resource Center, to the Financial Literacy and Education Commission’s My Money resources.

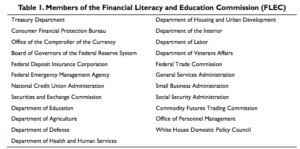

Financial Literacy and Education Commission

The Fair and Accurate Credit Transactions Act of 2003 established the Financial Literacy and Education Commission (FLEC), under the Department of Treasury’s Office of Consumer Policy. The Commission, comprised of over 20 federal agencies from the Departments of Defense and Labor to the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the Small Business Administration, was tasked with developing a national strategy on financial education and a national financial education website, MyMoney.gov, through which consumers can access financial education tools and resources.

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) was established as part of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Project Act after the 2008-2009 financial crisis. The CFPB has oversight of “consumer financial products…including checking and savings accounts, payday loans, credit cards, and mortgages,” and is also tasked with conducting financial education programs. Through these programs, CFPB protects consumers by empowering them “to help themselves, protect their own interests, build skills, strengthen their financial decision-making, and choose the financial products and services that best fit their needs,” says Director Kathleen L. Kraninger.

The CFPB’s interactive programs have had success, with many receiving “helpfulness” ratings of at least 80%. In 2019, over 5.4 million people used the Ask CFPB education tool for resources, how-to guides, and answers to common financial questions.

Overlap

The CFPB’s program successes stand out amongst the multiple education activities and programs across a number of federal agencies. According to the Treasury Department, this is primarily because many of these programs lack “reporting and metrics for measuring program effectiveness.” Additionally, there are over 40 federal websites on financial education topics, “resulting in a fragmented and confusing system for providing information to the public.” Reports from the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the Government Accountability Office (GAO) have long noted that “financial education activities exist in many different agencies, often without a requirement that they use or build on programs or resources already paid for by taxpayers.”

For example, the CFPB does not consolidate any of the existing financial education programs across various federal agencies, and the Treasury Department describes the FLEC as “an information-sharing body among federal agencies with limited success advancing a national strategy to promote access to quality financial education for all Americans.”

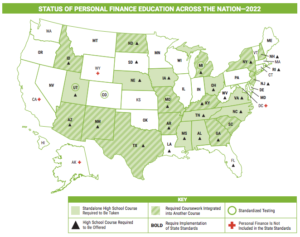

State Level

In the chart above, only a very small portion of $300 million in federal funding for financial literacy goes to K-12 and post-secondary education. In the U.S., education is primarily a state and local responsibility. According to the Department of Education, “it is States and communities, as well as public and private organizations of all kinds, that establish schools and colleges, develop curricula, and determine requirements for enrollment and graduation.” In fact, the Department of Education estimates that at the elementary and secondary levels, over 90% of all education funds come from non-Federal sources.

This means that deciding whether and how to incorporate financial literacy education into education curricula is left to the states. It also means that when citizens petition for more financial literacy education in their school districts, they are addressing their concerns to state and local governments, school districts, and boards of education. As a result, many endeavors are state-based public-private partnerships, such as the New Jersey Coalition for Financial Education, the Tennessee Financial Literacy Commission, and the Finance Authority of Maine.

You can use the Department of Education’s Resource Map to access your state’s department of education and see administrators, offices, services, and resources.

Role of the Private Sector

Financial institutions mainly improve financial literacy by offering financial services, with a particular focus on retirement planning. The CFPB estimates that financial institutions invested about $160 million on financial education. Nonprofits in this sector are dedicated to a variety of financial literacy challenges, such as publishing research and national statistics or providing educational resources. Many state and local governments across the country have been engaging in public-private partnerships with financial institutions and organizations to tackle financial education and literacy challenges. For example, the Bank On Program, which started in San Francisco and has since expanded across the country, focuses on expanding financial resources to unbanked populations. The State Financial Officers Foundation brings together leaders from the public and private sectors to share best practices and help state financial officers implement fiscally responsible public policy.

The Treasury Department says non-government entities including nonprofit organizations and the private sector are better able “to respond to needs more quickly, develop customized strategies to deliver financial education, and remain engaged and follow up with those served over time.” This has allowed a wide variety of organizations and private sector companies to take on various aspects of financial literacy and education. There are organizations that strive to implement financial literacy education standards in schools, such as Council for Economic Education and Junior Achievement; organizations geared towards women, such as Smart Women Smart Money and Ellevest; and organizations that offer educational financial literacy courses, programs, and resources, such as EVERFI, Savvy Money, Rock the Street, Wall Street, and the Job Creators Network. Find an organization in your state with Jump$tart State Coalitions Map.

The Treasury Department says non-government entities including nonprofit organizations and the private sector are better able “to respond to needs more quickly, develop customized strategies to deliver financial education, and remain engaged and follow up with those served over time.” This has allowed a wide variety of organizations and private sector companies to take on various aspects of financial literacy and education. There are organizations that strive to implement financial literacy education standards in schools, such as Council for Economic Education and Junior Achievement; organizations geared towards women, such as Smart Women Smart Money and Ellevest; and organizations that offer educational financial literacy courses, programs, and resources, such as EVERFI, Savvy Money, Rock the Street, Wall Street, and the Job Creators Network. Find an organization in your state with Jump$tart State Coalitions Map.

Financial institutions are another essential resource, from TD Ameritrade’s Education Center to Merrill Lynch’s WomenInvested to Bank of America’s Better Money Habits with Khan Academy. Local financial institutions may also have special programs. For example, Wintrust Community Bank, a regional bank in Chicago, has a Junior Savers program to teach children about money management. Employers offer resources as well; many companies have programs that help recent college graduates manage and eventually pay off student loans.

Challenges and Areas for Reform

Measuring Financial Literacy

Financial literacy and education programs across federal agencies lack a method of measuring their impact on the general public. If one were to exist, how should it be measured? Financial education standards or core competencies can provide a means for evaluation, but primarily for financial skills such as basic mathematical and financial concepts. Knowledge of financial literacy concepts is a good place to start, but where does asset management – including managing intangible assets such as your education and life experience – fit into the mix? These components of financial education are not necessarily something that can be taught in a classroom.

The CFPB began to explore these aspects of financial capability with a Financial Skill Scale that measures not only financial knowledge, but also the skills needed to act upon and put that financial knowledge to use. After measuring skills and applications, the CFPB also took a step towards measuring outcomes. Its Financial Well-Being Scale is a set of 10 questions for consumers to use to measure their financial well-being. The questions are based on research to develop “a consumer-driven definition of financial well-being…to allow practitioners and researchers to accurately and consistently quantify, and therefore observe, something that is not directly observable – the extent to which someone’s financial situation and the financial capability that they have developed provide them with security and freedom of choice.”

Teaching Financial Literacy

According to a 2022 Investopedia study, half of Americans feel they possess a strong understand of financial literacy basics, but “far fewer have the same level of understanding when it comes to investing and digital currency.”

Only 28% of undergraduates surveyed in the 2015-2016 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study could correctly answer three financial literacy questions. A 2018 study found students from states with high school financial education course requirements had higher credit scores, and the Council for Economic Education found financial education requirements were related to a decreased likelihood of holding credit card balances.

A growing number of states have been taking action to address financial literacy. For the 2021 legislative session, thirty-eight states, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia introduced financial literacy legislation. According to the Council for Economic Education’s 2022 Survey of the States, 25 states require economics classes in high school for graduation and 23 state require students to take a course on personal finance.

The Council for Economic Education’s 2022 Survey of the States, there has been progress in personal finance by stagnation in economic education; 22 states required economics for graduation in 2011, and that number has only risen to 25 in 2022. Overall across the nation, fewer states are requiring students be tested in economics in 2021 than in 2011. According to an The Nation’s Report Card on Financial Literacy from the American Public Education Foundation, there is still room for improvement: 12 states, Puerto Rico, and Washington, D.C. earned grades of “D” or “F,” 21 states earned grades of “C,” and 17 earned grades of “A” or “B.”

Curriculum Standards

The Council for Economic Education established in 2013 a set of national standards for financial literacy. A strong curriculum can help students, but flexibility is another important component. For many schools and districts, introducing new classes presents funding and staffing challenges. Staffing in particular is critical; a survey of 800 teachers by the George Washington University’s Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center found 90% believe personal finance should be taught in schools, but half admit to not having a solid enough understanding to teach financial literacy themselves. Both the Council for Economic Education and the Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center offer free training and resources to better equip teachers so they can teach these concepts to students.

Other companies such as EVERFI have developed digital learning tools that also help deliver this content to students in schools across the country without strains on finances or teachers. Additionally, collaborations between the private sector and nonprofit organizations provide influential opportunities for students. The Chicago-based Big Shoulders Fund’s Stock Market Program, for example, brings business professionals into classrooms to teach and share knowledge with students about investing and the financial industry. The Charles Schwab Foundation announced it plans to make personal finance courses available for free in every middle and high school in the U.S. by 2025, and will train roughly 25% of its U.S. employees as volunteer instructors. The program, called Moneywise America, is designed with the Council for Economic Education and Jump$tart Coalition.

Student Loans

Of the almost 45 million borrowers with student loan debt, 7 million are delinquent or in default on their loans. Addressing financial literacy in high school, or even earlier in students’ careers, can better equip students with financial knowledge to plan for college or other post-secondary pursuits. For example, the Council for Economic Education’s Survey of the States found state high school financial literacy requirements were related to increased applications for grants, aid, and other low-interest loans among students. Another available resource are 529 College Savings Programs, investment vehicles to save for future education costs. The National Association of State Treasurers created the College Savings Plans Network, which offers resources to 529 plans in each state.

Continuing this education and ensuring resources are available for students in college can also help students during their post-secondary schooling and after graduation. Georgia State University used a variety of methods, including financial advising and consistent communication for students, and incentives for students to boost their grades and qualify for scholarships. The combination of approaches helped to reduce the average time students took to complete a degree by half a semester, which was estimated to have saved the class of 2016 approximately $15 million in tuition and fees as compared with earlier cohorts. Federal work-study programs are another means through which students can meet the costs of higher education while also gaining valuable work experience.

Destigmatizing Talking about Finances

In T. Rowe Price’s 2018 Parents, Kids & Money Survey, a full third of young adult respondents said money was a taboo subject while growing up and over 40% described their parents as reluctant to discuss finances with them. Only 15% of parent respondents said they had financial discussions more than a few times a month with their children. This trend appears to have been altered by the pandemic, with 44% of kids and 43% of parents reporting in the 2021 survey having more money conversations since the pandemic began.

Economist Ryan Decker explains that, despite 20 years of education and work experience in the economics and finance sector, it was one upper-level elective course that gave him any idea about personal finance and how to manage money. He breaks down the importance of teaching, learning, and talking about personal finance (13 min):

Having conversations within families can help eliminate the discomfort that sometimes comes up in discussions about money and finances. Warren Buffett, CEO of Berkshire Hathaway, is in agreement: he created an animated children’s series called “Secret Millionaire’s Club,” each episode of which tackles a different financial lesson meant for children to learn and use in business and life.

A spring 2021 survey from CreditCards.com found that 37% of U.S. adults said friends and family were their top resources for financial advice, indicating stigma may be lessening for some. Still, 31% said they get no financial advice at all, and 43% said they had taught themselves the most about managing money.

Confidence and Personal Responsibility

If children have exposure to financial concepts, they will be less inclined to view money and finance as taboo subjects. This in turn can help build financial confidence at a young age that allows individuals to learn through experience and practice as they grow. Regulations can only do so much; “formal policy and consumer protections against fraudulent and predatory practices” cannot protect people from making poor financial decisions, says Professor Joyce Serido of the University of Minnesota. Instead, consumers must take it upon themselves to “understand their responsibilities and their rights about saving and spending decisions.”

Having access to credible resources outside of school or household environments is another integral component of ensuring financial well-being. Financial advisors, such as tax professionals, wealth managers, and financial planners, can offer advice on anything from long-term planning and avoiding fraud to understanding investments and financial risk. Financial coaches have a slightly different role. J. Michael Collins, faculty director of the Center for Financial Security at the University of Wisconsin describes the unique role of financial coaches (2 min):

Dave Ramsey, financial author, radio show host, and founder of Ramsey Solutions, describes financial coaches in particular as a “personal money mentor,” because financial coaching takes into account one’s individual circumstances and goals, and then tailors a plan to make those goals a reality. Whether clients plan to buy a home, change professions, or fund higher education, coaching can offer “encouragement and support to adhere to positive financial behaviors” and provide “a much-needed boost to self-control” for clients.

According to CreditCards.com’s spring 2021 survey, about a quarter of U.S. adults turn to financial institutions, financial websites, and financial advisers for financial advice.

Breaking Cycles

The taboo, intimidation, and even embarrassment associated with finances keep people from having important financial discussions. “When you ignore your financial situation,” says Shannon McLay, founder of The Financial Gym planning firm in Manhattan, “minor problems happening on a regular basis build up to very substantial challenges.” When not addressed, these challenges perpetuate financial difficulties within families that can even extend from generation to generation, called intergenerational poverty.

The Georgia Center for Opportunity’s Intergenerational Poverty Project survey found 65% of parents surveyed have had utilities shut off and teens acknowledge their families “are struggling from paycheck to paycheck.” At the same time, 59% of parents and 66% of teens in families experiencing intergenerational poverty defined their financial situation as “on solid footing,” and 63% of parents and 64% of teens said they would define their financial situation as the same or better when compared to others.

The Georgia Center for Opportunity’s Intergenerational Poverty Project survey found 65% of parents surveyed have had utilities shut off and teens acknowledge their families “are struggling from paycheck to paycheck.” At the same time, 59% of parents and 66% of teens in families experiencing intergenerational poverty defined their financial situation as “on solid footing,” and 63% of parents and 64% of teens said they would define their financial situation as the same or better when compared to others.

Regardless of circumstances or level of income, if individuals do not see their current situation as problematic, there will be little impetus to address behaviors or change habits. Removing the taboo of talking about money leads to learning and the ability to identify problematic situations. With more learning comes more knowledge about where to find reliable resources, and opportunities that build the confidence individuals need to take control of their financial well-being.

This thinking has prompted the implementation of financial education components for individuals from low-income backgrounds, such as families receiving social safety net benefits. In Delaware and Oregon, for example, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program recipients have access to financial coaching services. For more on TANF and similar programs, see The Policy Circle’s Entitlements Brief.

Prison inmates are another population that can benefit from financial education opportunities. Having a basic “understanding of how to manage personal finances and efficiently allocate earnings are crucial components of ensuring offenders do not turn back to crime in desperation,” explains the Center for Financial Inclusion. According to a RAND Corporation study, prisoners who participated in such educational programs were 13% more likely to gain employment after release than prisoners who did not participate.

Population Focus: The U.S. Military & Veterans

According to Eric Elbogen, Professor in Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Duke University, “a sometimes overlooked factor in veteran homelessness is difficulty with financial literacy.” A 2013 study of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans by Elbogen and colleagues found “a consistent correlation between money mismanagement and homelessness overall…regardless of income level, demographics, or clinical factors such as post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or traumatic brain injury (TBI).” In fact, in terms of predicting future homelessness among veterans, financial management proved to be just as important as income.

by Elbogen and colleagues found “a consistent correlation between money mismanagement and homelessness overall…regardless of income level, demographics, or clinical factors such as post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or traumatic brain injury (TBI).” In fact, in terms of predicting future homelessness among veterans, financial management proved to be just as important as income.

Resources

One of the first financial protection measures for military service members was the Military Lending Act of 2006 (MLA), which set a limit on payday loan interest rates for active military members and their families. A Department of Defense study found members of the military are as much as four times more likely than civilians to take out payday loans, and that some of the largest concentrations of payday lending businesses are around military bases. Some studies have even found lenders can circumvent the MLA, particularly because veterans are not covered by these protections. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau offers resources specifically for military families and veterans who can be targeted by scams.

Instead, in response to the awareness regarding the importance of financial literacy, the Department of Defense established in 2016 an Office of Financial Readiness. Each military department has since implemented programs to “provide members of the armed forces comprehensive financial literacy training,” including a required personal financial management training course, optional financial services and classes offered on military bases, and financial classes during a one-week Transition Assistance Program during discharge. The Department of Defense also offers financial counseling for members and spouses and has a statutory obligation to conduct an annual evaluation to measure the impact of this financial literacy training.

Additionally, the Department looked to the private sector for further assistance; in 2017, the Army Reserve began working with personal finance expert Suze Orman to “strengthen soldiers’ financial readiness through an informational video series, town hall discussion, base visits, and written material.” Also in the private sector are organizations such as the Wounded Warrior Project, which has a financial education program. Syracuse University’s Institute for Veteran’s & Military Families was co-founded with JP Morgan Chase and has financial resources and programs for the military-connected community.

Outcomes

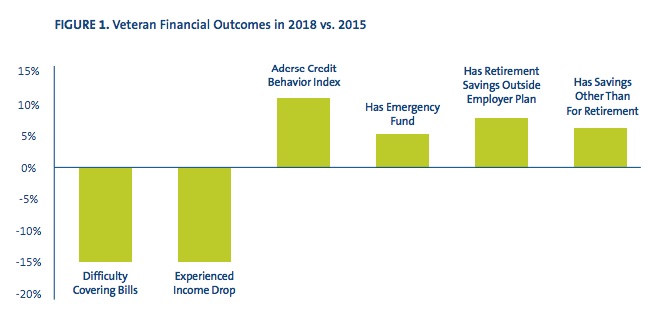

A Status of Forces Survey indicates the investment in financial training for military service members has been beneficial, with many even “demonstrating fewer financial problems and more constructive financial habits than the population as a whole” and having higher average levels of financial well-being, based on the CFPB’s scale. Data from 2019 indicate about 70% of military personnel survey were comfortable with their finances and able to make ends meet, although this data also do not capture potential impacts from the Coronavirus pandemic.

The U.S. Financial Capability Survey focusing on veterans also notes some of the benefits of the military’s financial training. Compared to veterans surveyed in 2015, veterans surveyed in 2018 (after the establishment of the Office of Financial Readiness in 2016) were less likely to have difficulty covering expenses or have experienced a drop in income, and were more likely to have an emergency fund and have savings.

However, the study did find increases in problematic credit card behavior among veterans between 2015 and 2018, and female veterans compared to male veterans in 2018 reported higher levels of financial stress and lower levels of financial self-efficacy. The main U.S. Financial Capability Survey also noted veterans are more likely than non-veterans to have taken a loan or withdrawal from their retirement accounts. Data from 2019 show over one-third of service members reported having no or less than one month of emergency savings, and 20% of service members spend all or more of their income on a monthly basis.

In a 2021 Military Family Lifestyle Survey, over half (53%) of all post-9/11 veteran respondents said they were experiencing financial stress, with 30% citing excessive credit card debt; 24% citing unemployment or underemployment; and 22% citing student loans.

Conclusion

Despite the millions of dollars of spending on financial literacy education at the federal level, our citizens still lack the basic financial capabilities of planning, saving, and investing that foster self-sufficiency. Inconsistent quality and mandates across states have left individuals without the knowledge, skills, and support they need to make the best financial decisions they can.

This doesn’t stop at the individual level, either: “Financial literacy and education should be seen as a vehicle to guard against market failures and foster competitive markets.” Education initiatives and knowledge-sharing endeavors that start with states, local communities, and individuals hold the keys to successfully delivering this knowledge. Each individual that is capable of managing their finances not only helps themselves but also helps others by contributing to the economic system and economic freedom.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Find out what your state and district are doing about financial literacy, and see what other resources are available in your state. There are many non-profits and other conferences, organizations, financial advising companies, banks, credit unions, insurance companies, and financial counseling services that have developed great programs.

- What is your state policy on financial education requirements?

- What financial literacy or related courses are offered at your district’s schools?

- How financially literate is your state? (WalletHub survey or National Financial Capability Map)

- Is there a coalition or task force on financial literacy in your community or state? Does one need to be formed?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, city council members, boards of education, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Who are the members of boards of education in your district?

- Who in your community is a subject matter expert? Consider financial institutions, professionals in the financial field, or teachers.

- Which journalists or media outlets cover education or economics and personal finance in your state or community?

- Who is your state treasurer or financial officer?

- Congress holds the power of the purse – who are your representatives?

Reach Out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of our immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in your state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with community organizations, school board members, financial institutions, and professional associations.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, communications@thepolicycircle.org, for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policymakers, and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Educate yourself – read frequently, explore courses that are offered at your community colleges, or see what resources may be available at your community organizations, local financial institutions, or businesses.

- Educate others – can you be a mentor through a community organization, financial institution, or with your school district?

- Organizations such as Secure Futures, Rock the Street, Wall Street, and Lakeland University’s Office for the Advancement of Free Enterprise Education Economics for Heroes Program look for volunteers who can teach personal finance and financial education. Look for similar organizations is your community.

- Talk it out with children – consider if there’s a way to include your children in conversations about money or activities like budgeting and grocery shopping.

- Hold your public officials accountable. Ask your representatives in Congress which committees oversee financial literacy education, or the effectiveness of these programs.

- Advocate for financial literacy in your state – take a look at the Council for Economic Education’s Advocacy Toolkit to get started.

- Plan ahead – paint pictures of your 5-, 10-, or ever 20-year visions for yourself. What do they entail? Consider working with the resources at your disposal, finding a financial advisor, or opening an investment or savings account.

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.

Thought Leaders and Resources

For Communities

Cities for Financial Empowerment

NeighborWorks America – Training and Professional Development

Center for Responsible Lending’s State-based policy and resources

For Individuals

Center for Responsible Lending

Danny DeMichele: Women’s Business Resources

The Simple Dollar: Minority Woman-Owned Business Guide

Online Resources

Council for Economic Education

Better Money Habits (Bank of America + Khan Academy)

TD Ameritrade’s Education Center

J. Michael Collins, University of Wisconsin

Scott Nierderjohn, Lakeland University

We would like to thank the following contributors for their assistance and advice during the creation of this brief:

Helen Crawley-Austin, Founder of Mastering Money with Helen Crawley-Austin

Amanda Muldoon, Account Management and Support Manager, representative of 3Rivers Federal Credit Union (Fort Wayne, IN)

Derek Kreifels, President, State Financial Officers Foundation and Smart Women Smart Money

Lorraine Gavican Kerr, Managing Director, Investor Education & Content at TD Ameritrade, Inc.

Patricia Besser, Managing Director, Private Client Advisor at Bank of America

Robin King, Chief Executive Officer, Navy SEAL Foundation

Sandra Lawson, Executive Director, Global Markets Institute, Goldman Sachs

Stephanie Rader, Partner, Goldman Sachs

Paris Forest-Hadley

Dana Slaby

Elizabeth Taylor

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.