Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

Elections are often determined by a small number of votes. Some elections are won with margins of less than 50 votes, such as the 2018 elections for the Idaho Senate District 15 (6 votes), the Washington State Senate District 42 (46 votes), the Minnesota House of Representatives District 5A (11 votes), and the Illinois House of Representatives District 54 (43 votes). In 2017 in Virginia, a single vote was thought to have resulted in candidate Shelly Simond’s election, but the election was later determined to be a tie after a poll watcher reported that a discounted ballot should be counted and a panel of judges agreed. Every vote counts.

Listen to Trust Your Voice Podcast for an audio version of this brief.

Elections are the means by which voters select their leaders and representatives. This is a foundational principle of our democracy. Elections and voting “[give] people an opportunity to have their say” and provide an outlet for the expression of public opinion and discussion of important issues. Additionally, elections “serve to legitimize the acts of those who wield power,” and attend to problems of succession of leadership before they arise.

John Dickerson for Khan Academy explains in more detail why elections and voting matter (3 min):

In particular, “trust in the electoral process is integral to acceptance of the outcome as legitimate.” For the American public, ensuring a “secure and resilient electoral process” is essential to the interest and health of our democracy. “Our Republic flourishes when citizens are confident that their vote is free, fair, and secure,” says True the Vote founder Catherine Engelbrecht. Concern about election fraud and interferences, therefore, “ jeopardizes our entire system of government, eroding our trust in elected leaders and undermining our confidence in the system by which they govern – beginning at the polls and rising up through the highest offices in the land.”

Putting it in Context

History

In 1787, when the Founders wrote the Constitution, only one chamber — the House of Representatives — was directly elected by the people. The President was selected by the Electoral College, and senators were selected by state legislatures. The framers expected that senators elected by state legislatures would not feel pressure from the populace. But bribery cases and deadlocks plagued the Senate selection process; in fact, Delaware had so much trouble electing a senator that the state legislature did not send a senator to Washington between 1899 and 1903. The troubles led to a call for the direct election of Senators, which eventually became the law of the land through the 17th Amendment to the Constitution in 1913.

Early elections in U.S. history were infrequent and voters were not required to register in advance. During the late 1800s, the election process became more complex with the addition of voter registration, which required election officials to maintain lists of voters, and the exchange of open ballots for closed ones.

America’s first election took place on February 4th, 1789. George Washington was elected president and John Adams was elected vice president. TED-Ed takes us back to visualize what the first election was like (4 min):

Elections Basics

On the national level, congressional House and Senate elections occur every two years and presidential elections occur every four years. State and local elections take place in any year and at any time, such as for statewide elections of mayors and legislators or more local elections such as mayors. You can see your state’s upcoming election dates here.

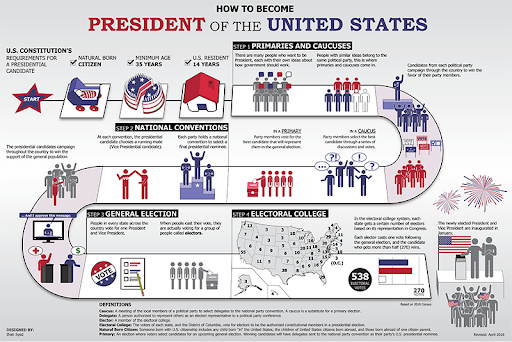

Primary elections and caucuses, the processes by which parties nominate candidates for the general election, take place anywhere from the late winter through summer depending upon the schedule set by state laws. General elections are held the first Tuesday of November in even-numbered years.

On an election day, voting takes place throughout the country in voting districts, also called election districts or precincts. These areas are divisions of a larger geographic area such as a city or county. In some areas, just one precinct votes at a single location. In other areas, many precincts vote together in a vote center. Voters in each precinct report to a specific location for voting, a polling place such as a school, church, or community center, where they may vote for federal, state and/or municipal candidates or initiatives. You can find your polling place here.

Voting districts are created by the state legislature in power at the time of the Census; some states require bipartisan or nonpartisan commissions to oversee the districting, while many do not. For more on how the Census affects redistricting, see The Policy Circle’s Decennial Census Deep Dive.

Ballots & Ballot Measures

Ballots at each voting location are tailored so that individuals only vote in elections relevant to them. Some areas use paper ballots, which are then fed into voting machines. Other areas vote electronically on “touch screen” machines that resemble ATMs. Having electronic ballots allows any ballot style within a jurisdiction to be programmed from any location. Outside of the polling place, mail-in voting or absentee voting allows individuals to receive their ballots by mail if, for example, they are unable to vote in person for reasons such as disability or being overseas. Different states have different rules for voting by mail.

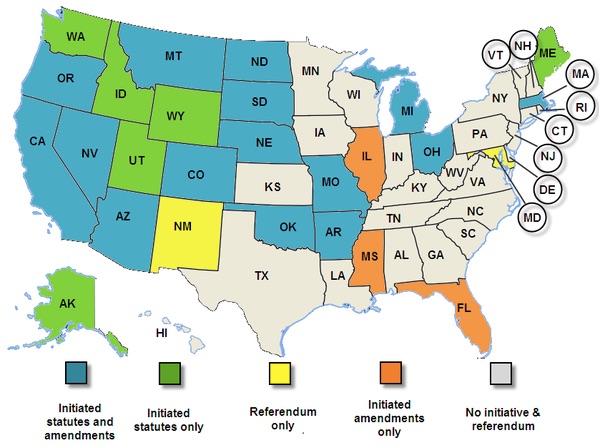

A ballot measure “is a law, issue, or question that appears on a state or local ballot for voters to decide.” All fifty states allow statewide ballot measures on ballots, and 49 states require a ballot measure if they are considering making a change to the state constitution. In most states, ballot measures are statutes or amendments referred by the state legislature, such as tax increases, or advisory questions that do not actually change the law but are meant to gauge voter opinion.

In 26 states, citizens are allowed to initiate amendments or statues by collecting signatures in support of placing a measure on the ballot. Such a measure, called a ballot initiative, is essentially “a petition signed by a certain minimum number of registered voters” to “bring about a public vote on a proposed statute or constitutional amendment.” It becomes law if it receives enough votes. For ballot measures in your state, visit the National Conference of State Legislature’s Statewide Ballot Measures Database, or contact your local or state election office. Ballotpedia’s Ballot Initiative Map illustrates initiative processes in each state.

Primaries, Caucuses, and Conventions

The primary and caucuses stage is an important part of the presidential election process. These forums provide an opportunity for individual citizens to be very influential in selecting the presidential candidates. Primary elections and caucuses are held in each U.S. state and territory as part of the nominating process.

The results of primaries and caucuses determine how many delegates each state awards to each nominee. Primary elections are financed and run by state and local governments; just like in the general election, voters go to a polling place and cast their vote. Caucasus are private events run by state political parties. Individuals are identified by the party as potential delegates, and the party then has an informal vote to determine who will serve as delegates to represent the state at the national party convention. Conventions “finalize a party’s choice for presidential and vice presidential nominees” through a vote of delegates. Read on about the difference between primaries and caucuses.

The Washington Post breaks down how the Iowa Caucus works (2 min):

Some states have open primaries, meaning any voter can participate in primary elections regardless of political party. In other states, voters must be affiliated with a party in order to vote in that party’s primary. See the laws in your state here.

The Electoral College

Although we directly elect both our Representatives and our Senators, our President is ultimately selected by the Electoral College. The Electoral College system “gives all American citizens over the age of 18 the right to vote for electors, who in turn vote for the president. The president and vice president are the only elected federal officials chosen by the Electoral College instead of by direct popular vote.” Each state has as many electors as it has members of Congress.

TED-Ed explains (5 min):

See how many electoral votes your state has here, and see The Policy Circle’s Electoral College Deep Dive for more.

The Role of Government

Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution provides the original guidance on elections being within the purview of the states. While there have been amendments and legislation since, the general rule is that states oversee elections. Over the past 50 years in particular, however, the federal government’s role in elections has increased.

Federal

The Constitution limits the role of the federal government to specific tasks that mostly support states and localities with elections. This includes providing states with Census data to facilitate redistricting, providing funding to update election equipment, and assisting states with election security threats. Additionally, the federal government takes authority over voting rights by passing voting rights laws.

Legislation

The Civil Rights Acts (first outlined in the Civil Rights Act of 1870 and subsequently amended in 1957, 1960, and 1964) established federal protections against discrimination in voting, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 added additional protections based on race and language.

The 1993 National Voter Registration Act (also known as the NVRA or the Motor Voter Act) was enacted “to enhance voting opportunities for every American. The Act has made it easier for all Americans to register to vote and to maintain their registration” by requiring states “to provide eligible prospective voters the opportunity to apply to register to vote for federal elections via mail; when they apply for or renew a driver’s license; or at any office that provides public assistance or state-funded programs.

The Help America Vote Act (HAVA) in 2002 required states to implement provisional voting, to provide voters with voting information, to update and upgrade voting equipment and statewide voter registration databases, and to develop voter identification and administrative complaint procedures. Additionally, the act authorized federal funding to help states meet these standards and improve election administration, and established the Election Assistance Commission (EAC) to assist states and distribute funds.

Congress

The House and Senate Appropriations Committees appropriate funds for elections to the states. Congress also plays an important role in overseeing federal elections (the House Administration Committee and the Senate Rules and Administration Committee), certifying congressional electoral college results (the House and Senate together), and resolving contested elections (either the House or the Senate, depending on the contested race).

The Election Assistance Commission

The Election Assistance Commission (EAC) is an independent, bipartisan commission “charged with developing guidance to meet HAVA requirements, adopting voluntary voting system guidelines, and serving as a national clearinghouse of information on election administration.” The EAC additionally creates voting system guidelines and operates the federal voting system certification program, maintains the National Voter Registration form, certifies and tests voting equipment, and serves as a resource for states and localities by conducting voting and election-related research.

The Federal Election Commission

The Federal Election Commission (FEC) is an independent regulatory agency that administers and enforces federal campaign finance laws pertaining to U.S. Congressional, Presidential, and Vice Presidential Campaigns. On the whole, the federal government plays a much larger role in overseeing campaigns than it does in overseeing elections. To explore these intricacies, see The Policy Circle’s Deep Dive on Campaign Finance.

State and Local

The decentralized election administration in the U.S. leaves states and localities primarily responsible for administering elections. This ranges from determining voter ID requirements and voter eligibility to purchasing voting equipment, and means “that no state administers elections in exactly the same way as another state, and there is quite a bit of variation in election administration even within states.” On the one hand, this can create problems related to inconsistent application of laws. On the other hand, it allows individual districts to experiment and innovate with procedures that are best for their particular circumstances.

For example, states are in charge of elections during emergency situations like natural disasters or other situations that may impact an election. State election officials work closely with emergency management departments, the governor’s offices, and other state agencies to assist local election officials in developing contingency plans and procedures, such as how to provide important voting information to individuals impacted by emergency situations. The federal government has only assisted in emergency situations impacting an election in 1992 in Florida after Hurricane Andrew, after the 9/11 attacks in 2001, and in 2006 in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina.

Election Officials

Each state appoints a chief election official or board that has authority over elections that occur in the state. Roughly half of the states select the secretary of state to serve as the chief election official, but other states have an election official or a board or commission appointed by the governor. Duties include designing, coding, and distributing ballots; certifying candidates; testing and delivering voting equipment; ensuring local officials adhere to election laws; administering the statewide voter registration database; and calculating results. The National Conference of State Legislatures breaks down selection methods at the state and local levels.

At the local level, either a single individual or a commission (or a combination thereof) administer elections. Larger jurisdictions may have a dedicated election administrator, but smaller counties may have a county clerk or registrar that serves as the election official. If election duties are divided among multiple offices, it is most likely that one office, board, or official handles voter registration and the other oversees actual election administration on election day.

The National Association of Election Officials conducts seminars and workshops in addition to a certification program for election officials. The National Association of Secretaries of State (NASS) and the National Association of State Election Directors (NASED) also provide a forum for state election officials to exchange best practices.

Current Challenges and Areas for Reform

Election Fraud

Election fraud has occurred in every state. Examples of fraud include:

- Impersonating a voter by using the name/identification (such as a fake voter registration card) of another person

- Registering under a false name or address

- Ineligible voting by individuals who are not registered, not U.S. citizens, or are convicted felons who have not regained the right to vote, etc.

- Duplicate voting, such as by requesting a mail-in ballot and voting on election day

- Buying votes by bribing legally registered voters to vote a certain way

- Stuffing the ballot box, indicated by boxes filled at or near 100% (such as one Georgia precinct with a 243% turnout)

- Coercing or intimidating voters to cast fraudulent ballots. This can happen outside the polling location, such as in nursing homes where populations of elderly and/or disabled voters may be taken advantage of. Sometimes a nursing home will apply for ballots for all of its residents, regardless of their desire to vote. Those assisting voters at nursing homes may also fail to read all the candidate names, not fill out the ballot according to the voter’s decision, prompt the voter to vote in a certain way, or submit a ballot even though the voter has declined to vote.

The good news is there are safeguards against most of these types of voter fraud. The Election Assistance Commission gives a behind-the-scenes look at what goes into securing an election (5 min):

Vigilant election officials or poll watchers act as the last line of defense against fraud. Voters can serve as poll watchers, also called election observers, whose job it is to observe the polling place on election day to ensure equipment is properly tested, voters cast their ballots, and officials count results. Partisan citizen election observers are appointed by political parties or candidates, and nonpartisan citizen election observers are appointed by non partisan organizations or civic groups. Poll watchers need to participate in training sessions in order to serve and are usually required to be registered voters, but each state has specific qualifications. Look at your state’s qualifications or see The Policy Circle’s Active Voter Guide for how to be a poll watcher.

Voter Identification

In the U.S., 35 states have laws either requesting or requiring voters to have some form of identification when they vote at their polling location. Depending on the state, voters may be required to bring photo identification with them (such as a driver’s license, a military ID, or a voter registration card) or the state may accept non-photo identification (such as a bank statement with a name and address). In the case of a voter lacking proper identification, they may be able to cast a provisional ballot, which would only be counted after the voter’s identification is verified. Ballotpedia, the National Conference of State Legislatures, and Rock the Vote break down voter ID requirements by state.

Proponents argue that such requirements prevent voter impersonation, and this protects and boosts confidence in the election process. Critics argue that voter fraud is rare, and a working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) determined ID laws seemed to have “no significant impact on fraud or public confidence in election integrity.” Additionally, there are concerns that strict voter ID laws can place an undue burden on voters since between 5% and 20% of eligible voters lack an accepted form of identification. The Federalist Society breaks down the arguments (5 min):

Studies of the effects of voter ID laws on voter turnout are mixed. In a review of ten studies on voter identification laws by the Government Accountability Office, five found ID requirements had no statistically significant effect on voter turnout, another four found statistically significant decreases in voter turnout, and one found an increase in voter turnout. The NBER working paper did not find strict voter ID laws to have a significant negative effect on voter turnout “for any subgroup defined by age, gender, race, or party affiliation. Meanwhile, a study by the University of Wisconsin-Madison found strict voter ID laws in place during the 2016 election reduced voter turnout in Dane and Milwaukee Counties by about 2%, and that “burdens of voter ID fell disproportionately on low-income and minority populations.”

In Crawford v. Marion County Election Board (2008) the Supreme Court ruled Indiana’s strict photo ID requirement was not burdensome, but warned that ID requirements could be challenged if they did burden voters. This prompted states with strict identification laws to offer free voter IDs to those who lack forms of accepted government-sponsored identification. A study by Harvard Law School found free IDs can still be a burden especially for low-income individuals or minorities who must factor in costs of travel to state agencies, wait times at these agencies, and even legal fees needed to secure government-issued documents. Ensuring avenues exist for all voters to meet the requirements of voter identification with ease can help balance enfranchisement for all voters and confidence in the electoral system.

Voter Registration Records

State election officials are obligated by federal law to keep voter registration records as up to date as possible. This not only means adding new registrants to the list, but also sometimes canceling registrations. In the case of people who have died, moved to another state, or have become legally incompetent, this is important to prevent anyone from impersonating them and trying to vote in their place.

This holds true for convicted felons, whose voting rights vary from state to state. In 48 states, convicted felons are not allowed to vote while incarcerated, but most can regain the right after release. This may require completing their sentence, probation, or parole, and paying any outstanding fines or fees before their rights are restored. You can see your state’s specific requirements here. Once their voting rights are restored, prison officials inform election officials, and the individual is responsible for re-registering to vote.

Some states have gone beyond these examples and have removed people from voter registration lists “because they have skipped voting in several consecutive elections and they have not responded to a letter asking them to confirm where they live.” Some argue that updating registration lists is absolutely imperative for preventing fraud, and that people are contacted well in advance before they are removed. Others maintain this method of voter removal is a “purge” that turns voting rights into a “‘use it or lose it’” scenario, and that “American voters have the right to choose not to vote and not to be penalized for doing so.” Additionally, eligible voters can be removed from the registration list by mistake. In December 2019, Georgia removed 300,000 inactive voters from its registration list, but then reinstated 22,000 that had been taken off due to errors. This confusion can prompt suspicions with the process.

One suggestion is publicizing lists of the voters to be removed so any potential errors can be corrected. In 2019, Ohio Secretary of State Frank LaRose took the list of 235,000 names meant to be removed from the voting registration list and let voting rights groups “scour the data and see whether they could spot irregularities.” The group found over 40,000 names had been accidentally added to the list by county election officials or election software errors.

To help maintain voter registration lists, election officials can also turn to other sources such as change of address information from the Department of Motor Vehicles (although some states say they have trouble with this system) or the U.S. Postal Service’s Change of Address System. The Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC) is a state-managed nonprofit organization that helps states maintain accurate voter registration records. See which states participate here.

Vote-by-Mail

Each state has its own rules for mail-in voting that dictate under what circumstances voters are allowed to vote by mail. In eight states (California, Colorado, Hawaii, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Vermont and Washington), ballots are automatically mailed to eligible voters, but in-person polling locations are still an option on Election Day. Other states require voters to request mail-in ballots, also called absentee ballots, if voters are unable to physically vote at a polling place or would prefer to vote at home. Some states require voters to have a valid excuse, such as inability to vote in person due to illness, injury, disability, travel, or living arrangements outside of state such as college students or military members and their families. See your state’s requirements here.

Many voters express enthusiasm for mail-in voting, with some reports indicating the convenience of mail-in voting gives voters the time and ability to learn about all the offices and candidates on their ballot. Voting by mail, however, is not convenient for everyone and can even be exclusionary. Mail delivery is not uniform across the U.S., such as on Native American reservations, which is why even states with all mail voting still have the option to vote in person. Overall, the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research found that voting by mail “increases turnout rates modestly,” but that these turnout rates do not benefit one party over another.

Some jurisdictions report saving money by reducing staff and equipment at physical polling stations. Other jurisdictions report excess expenditures, as increased printing costs and costs for machines that are needed to scan paper ballots can add up.

Finally, while it is easier to catch fraud at polling stations because of voter ID laws and watchful election officials and observers, coercion or vote buying is a rare but very real possibility with a mail-in ballot. Counterfeit ballots, however, are practically impossible because a ballot’s size, style, and even weight are different from county to county, resulting in dozens of unique aspects of a ballot that would need to be copied perfectly in order for a machine to read it. According to the Heritage Foundation’s online election fraud database, out of 250 million votes that were cast by mail from 2000-2020, there were 204 cases of fraud.

The coronavirus pandemic reignited debates surrounding vote-by-mail, as there were questions regarding the safety of in-person voting during the November 2020 election. Some called for expanded mail-in ballot options since these “could prompt further emphasis on social distancing and dramatically lessen turnout.” Pushing too quickly for an all-mail system that does not guarantee enough in-person polling sites also had the potential to be risky, says David Becker of the Center for Election Innovation & Research. A sharp reduction in polling places could lead to longer lines for voters and administrative headaches for election officials. This has been the case as local and state election boards have closed over 1,500 polling places between 2014 and 2020. A large shift to vote-by-mail “requires planning, training, procurement of new technology and education of the electorate… Printing and secure storage of huge increases in paper ballots, postage, secure drop-box locations and additional ballot scanners all must be considered.” Expanding access to vote by mail while still ensuring there are enough polling stations to accommodate in-person voters will give all Americans voting options.

The Wall Street Journal dives deeper into the vote-by-mail debate (6 min):

See the National Conference of State Legislature’s list for state-by-state legislative action, including bills relating to vote-by-mail and delaying elections.

Cybersecurity & Election Interference

Freedom House, a nonpartisan organization that monitors and reports on the state of freedom and democracy around the world, notes there are three main forms of election interference:

Freedom House, a nonpartisan organization that monitors and reports on the state of freedom and democracy around the world, notes there are three main forms of election interference:

- Legal measures, through which authorities can hinder political expression

- Technical measures, which are used to restrict access to news sources or communication tools. For example, in 2019 Australia reported cyberattacks against computer networks three months before its parliamentary elections (linked to China) and Ukraine’s Central Election Commission faced cyberattacks during the presidential election (linked to Russia).

- Informational measures, when information is manipulated. This is the most common method; state and nonstate actors employed “informational measures to distort the media landscape during elections in 24 countries in 2019.” Since 2014, Russia has been linked to disinformation campaigns in Hungary, Germany, Finland, Spain, the UK, and the U.S., particularly by groups associated with Russia spreading disinformation across social media platforms.

In 2016, “Moscow launched a multipronged cyber operation during the presidential campaign that included the hack and leak of Democratic emails, the use of bots and trolls on social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, and the electronic probing of state election systems.” Intelligence officials have been warning lawmakers about intentions of foreign interference targeting the November 2020 elections. National Counterintelligence and Security Center Director William Evanina explains that “the diversity of election systems among the states, multiple checks and redundancies in those systems, and post-election auditing all make it extraordinarily difficult for foreign adversaries to broadly disrupt or change vote tallies.” Still, foreign influence particularly by China, Russia, and Iran and on social media are meant “to sway U.S. voters’ preferences and perspectives, to shift U.S. policies, to increase discord and to undermine confidence in our democratic processes.”

Protections Against Election Interference

Protections Against Election Interference

States are in charge of administering elections, but “the federal government is the leading actor in protecting the country from foreign attack. Thus when America’s election infrastructure is attacked by a foreign entity, responsibility for election cybersecurity falls to (or in between) both.”

Security

At the state and local levels, election officials can step up their security. Cybersecurity vendor Area 1 Security Inc. tracked over 12,000 local officials and found more than half of these officials used email systems with limited protections from phishing attacks. Over 660 were using their personal email addresses for election-related business, “a practice that could expose their work systems to impersonation or other forms of online fraud.” Officials in jurisdictions in Michigan, Missouri, Maine, and New Hampshire were using a software product that had been linked to online attacks by a Russian intelligence service and that the National Security Agency had warned was a target for online attacks.

Communication

According to the Report of the Select Committee on Intelligence, “the communication and cooperation went badly” between the federal government and state governments. The federal government reportedly alerted states of attempted intrusions in the summer of 2016, but made no mention of these attempts being from a hostile foreign power. Lack of necessary security clearance among state election officials meant federal officials spoke to the wrong people at the state level.

Operations

While giving more election officials security clearances could help, the National Background Investigations Bureau has a ballooning backlog of people waiting for clearances. Operational procedures also need to be considered. For example, state officials said the Department of Homeland Security “‘didn’t recognize that securing an election process is not the same as securing a power grid.’” Having policies and procedures in place that proactively address potential challenges in securing elections, instead of reacting after and emergency arises, will help protect our elections.

Voting Processes

Beyond ensuring the integrity of elections, some question the American election process as a whole and believe the system should be reformed to address ideological polarization. For a number of years, distrust and pessimism regarding American democracy has been growing; according to December 2021 Schoen Cooperman Research on U.S. perceptions of government (December 2021):

- 51% of voters say U.S. democracy is at risk;

- 26% believe U.S. democracy is secure;

- 85% of Americans concerned about political extremism;

- 67% say the country has become more divided in the past year;

- 80% of Americans “want elected officials to work together to solve problems as opposed to remaining true to their ideological beliefs, even if less gets done[.]”

This has led to calls to change election processes in the U.S. One method that has gained popularity in recent years, particularly at the local level, is ranked choice voting (RCV).

As described by Ballotpedia,

“Ranked-choice voting is an electoral system in which voters rank candidates by preference on their ballots. If a candidate wins a majority of first-preference votes, he or she is declared the winner. If no candidate wins a majority of first-preference votes, the candidate with the fewest first-preference votes is eliminated. First-preference votes cast for the failed candidate are eliminated, lifting the second-preference choices indicated on those ballots. A new tally is conducted to determine whether any candidate has won a majority of the adjusted votes. The process is repeated until a candidate wins a majority of adjusted votes.”

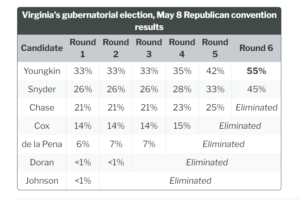

As of April 2022, 43 jurisdictions used RCV in their most recent elections, including the New York City mayoral race and Virginia gubernatorial race in 2021. The following graph illustrates how Glenn Youngkin won the Virginia gubernatorial nomination in May 2021 after 6 rounds of vote-counting using RCV:

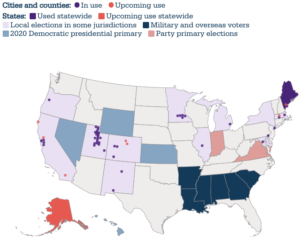

According to FairVote, 10 million voters in 52 cities, 1 county, and 2 states are projected to use ranked choice voting for all voters in the next election. Additionally, military and overseas voters cast RCV ballots in federal runoff elections in 6 states:

In New York, RCV was approved in a 2019 referendum, with the hope that it would draw more diverse candidates and prevent vote splitting among voting blocs. Critics maintained RCV would disenfranchise voters who might not have time to learn the process, particularly seniors, non-English speakers, and people without internet access. To combat this, the city conducted outreach in-person, online, and through multimedia, which included multilingual materials. Overall, there was a 29% increase in citywide turnout over 2013’s mayoral primary, which some take to indicate RCV did not suppress voters. Exit polls show 95% of voters surveyed found the ballot easy to complete.

Western Washington University’s Todd Donovan explains that RCV has the potential to allow voters to more fully express their preferences for candidates, as opposed to being allowed to choose only one. This could allow smaller parties to show their voters’ preferences are instrumental in getting a winning candidate elected. However, Lee Drutman of New America notes that whether or not RCV increases the number and diversity of candidates is unclear, as there are few examples to point to. The same goes for whether RCV reduces polarization.

To reduce polarization, the Institute for Political Innovation (IPI) goes one step further in proposing Final Five Voting, which would combine primaries and ranked choice voting in the general election. The argument for this method is that primaries as they are currently held lead candidates to move further to the left or right, increasing polarization. Additionally, the concept of plurality voting (whoever has the most votes wins, as opposed to whoever received the majority of votes) makes it difficult for anyone outside of the two-party system to make an impact. Katherine M. Gehl, IPI founder, explains how this process would work (17 min):

Conclusion

Needings to assess candidates, investigate ballot measures, and ensure proper identification can make anyone feel overwhelmed by an election, even without the added prospect of foreign interference, domestic fraud, and a decentralized voting system. Yet it is this same decentralized voting system that gives each of us the ability to make a difference. When Americans are aware of the problems facing elections, they can best determine and act on what can be done to address these challenges in their communities, by starting a ballot initiative, volunteering on election day as a poll worker, or reaching out to election officials and other community members.

Taking small steps at the local level allows each of us to do our part to protect against fraud and interference in elections while also ensuring all eligible Americans can easily express their right to vote. Your first hand involvement with the electoral process will set an example to others around you and possibly inspire their participation. This only helps grow the number of active and involved citizens, and ensures free and fair elections as envisioned by our Founders and enshrined in our Constitution. We have the ability to maintain our democracy, and our confidence in it.

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Find out what your state and district are doing to ensure free, fair, and secure elections.

- Do you know when your state’s upcoming elections are?

- What is the status of voter participation in your community or state?

- What are your state’s voter ID laws or requirements?

- What are your state’s election security policies?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Who are the contacts at your state or local election office?

- Who administers elections at your state and local level?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with neighbors or community organizations.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, communications@thepolicycircle.org, for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policy makers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Make sure you are registered to vote.

- Check your state’s registration deadlines if you are not yet registered and see if your state offers online registration.

- Talk to the young people in your life about registering or pre-registering to vote.

- Explore your ballot in advance, including candidates and ballot measures.

- Investigate your state’s process for ballot initiatives, and consider starting your own ballot initiative to bring an important issue to the attention of voters and legislators.

- Check your state’s requirements to be an election observer/poll watcher or a poll worker, and if you’re eligible and able, volunteer.

- See The Policy Circle’s Active Voter Guide for more ways to get engaged in elections.

- Are you or is someone you know voting for the first time in an upcoming election? Get started with The Policy Circle’s First Time Voter Guide.

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.

Additional Resources

US Vote Foundation Election Directory

Ballotpedia Elections Calendar

More information:

Brookings: Podcast – Protecting American elections from foreign interference

Indiana State Leadership Council’s deep dive on Women’s Suffrage

List of Common Terms regarding elections.

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.

Deep Dives

Want to dive deeper on Election Processes & Innovations? Consider exploring the following: