Introduction

Watch The Policy Circle’s 6th Annual Leadership Summit panel discussion, #1 Priority: Safety in Communities featuring a discussion on crime and safety in America:

View the Executive Summary for this Brief

In October of 2021, Nestor Hernandez was released from prison and placed on parole after serving time for aggravated robbery despite twice violating his parole conditions. Almost exactly one year later, on October 22, 2022, Hernandez was granted permission to visit the hospital for the birth of his child, where he first threatened his girlfriend in the maternity ward before he eventually shot and killed nurse Jaqueline Pokuaa and social worker Katie Flowers, all while wearing an active ankle monitor. After the shooting, Dallas Police Chief Eddie Garcia responded, sharing that he was “outraged at the lack of accountability in the justice system.”

In recent years, disturbing reports like this have flooded news and media channels, with concern surrounding the acts of violence and fatal consequences of a broken justice system. The surge of rising crime rates sparks concern. It weighs heavily on the minds of many Americans, with 61% of registered voters ranking crime in 2022 as “very important” when weighing political decisions.

Between 2019 and 2021, property crimes like robbery, burglary, and larceny went down, while homicide rates went up by 39.42% and aggravated assault went up by 14.9%. Similarly, while examining these trends on a local level, a report showed Chicago neighborhoods saw seven major crime categories spike to the highest levels since 2018. What does this mean for national crime data? What are the factors that are leading to this surge in crime?

A crime is a fact; an act is either criminal or lawful. Safety, however, is more nuanced because it involves perceptions and feelings. This Policy Circle Brief will explore crime, its effects on individuals, businesses, and communities, the challenges of crime data, and the role of government, including current challenges and ongoing measures of reform.

Case Study

The “Broken Windows” theory first published in 1982 in The Atlantic by social scientists George L. Kelling and James Q. Wilson, theorizes that minor signs of disorder in an area or community, like a broken window, may encourage further chaos and lead to environments where more significant crimes can occur. According to Rafael Mangual, the Nick Ohnell Fellow and head of research for the Policing and Public Safety Initiative at the Manhattan Institute, this theory “reflects an understanding of how we psychologically process information about visible disorder.”

While aspects of this theory have been heavily debated, a recent case study demonstrated the power of removing decay and disorder by restoring vacant and overgrown urban land. The study revealed significant impacts on crime rates and the feeling of safety from residents in the surrounding area.

In a randomized trial, vacant lots in Philadelphia were revitalized, including efforts of “cleaning and greening,” removing trash, planting grass and trees, and installing open, ungated low-level fences to encourage residents to visit the new greenery. Not only did residents living near the upgraded lots report significantly increased perceptions of safety, but data demonstrated that actual crime rates fell. Following the implementation of the upgraded and revitalized lots, crime rates dropped by 13.3%, gun violence dropped by 29.1%, and burglary rates fell by 21.9%.

The study found that with this reduction of gun violence, these efforts could “translate into over 350 fewer shootings each year if the vacant land interventions were scaled beyond just the location of the study, to the entire city.” Areas around the city demonstrated efforts to combat the broken windows phenomenon by organizing community improvement opportunities to clean up public spaces like parks, plant public gardens, and revitalize empty lots to discourage disorderly behavior and, ultimately, crime.

To learn more about this case study and other similar studies, watch the video below from Kite and Key Media:

Why It Matters

Merriam-Webster defines crime as “an illegal act for which someone can be punished by the government; a grave offense especially against morality; something reprehensible, foolish or disgraceful.” Safety is defined as “the condition of being safe from undergoing or causing hurt, injury, or loss.”

Safety is defined as “the condition of being safe from undergoing or causing hurt, injury, or loss.”

Crime and safety go hand in hand. Crime is more than a statistic because it impacts our sense of safety. Understanding how crime affects individuals and their perceptions, businesses, and communities helps us better gauge the safety of where we live, work, and how we engage with others in our local areas.

Individual Perceptions of Crime

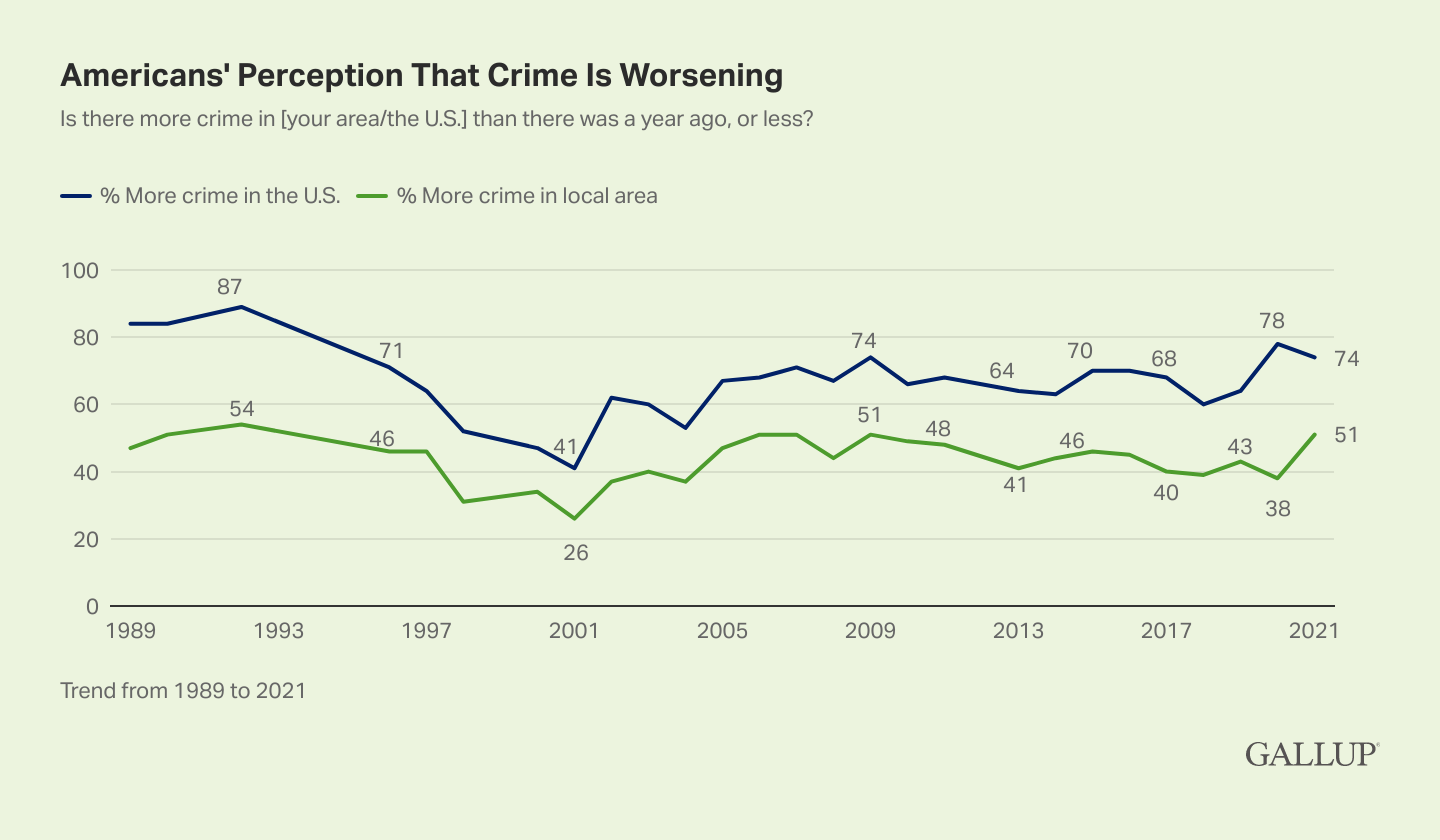

While crime, whether through direct or indirect experiences, impacts every individual differently, the perception of crime also plays a critical role in decisions on the individual level. According to a Gallup poll conducted in October 2021, 51% of Americans said they felt local crime worsened, up from 38% in 2020 – the highest level since 1972. In April 2022, Gallup reported 53% of Americans worried “a great deal” about crime – the highest uptick since 2016.

The rates of crime impact decisions made by an individual from where one lives, works, or spends time. Further, studies have shown that even just the perception of crime has “an adverse impact on life satisfaction beyond those associated with real crime.”

Crime Affects Businesses

Crime not only impacts individuals and their decisions on an individual level but also, directly and indirectly, impacts businesses. “Crime—burglary, robbery, vandalism, shoplifting, employee theft, and fraud—costs businesses billions of dollars each year. Crime can be particularly devastating to small businesses, who lose both customers and employees when crime and fear claim a neighborhood.”

Crime impacts businesses as well as consumer choices, and understanding how consumers respond to crime has critical implications for economic development opportunities. A recent study illustrated that higher levels and occurrences of violent crimes and property crimes are “significantly associated with both business failure and relocation.”

In August 2022, Starbucks announced more locations would close due to “a high volume of challenging incidents that make it unsafe to continue to operate, including drug overdoses in bathrooms and violent incidents involving theft.” Changing dynamics within cities and the subsequent perceptions of safety, alongside the changing crime rates across America, influences business on the local level as well as major corporations, ultimately impacting opportunities for continued community growth.

Crime Affects Communities

The impact of crime on both individuals and businesses directly shapes communities. The decline or failures of businesses due to crime, and even the mere perception of crime, can lead to drastic impacts on a community and reduce the appeal of neighborhoods over time. Businesses provide an “economic base of a neighborhood, and their closure or out-migration may initiate or exacerbate a cycle of decline, which itself may lead to heightened rates of crime.”

A recent study also demonstrated that crime rates impact businesses’ viability in general and reduces commercial property values and economic activity in communities. This decline often leads to residents migrating outside cities with higher crime rates in search of safer communities. To understand more about the reasons for relocation, and the role that crime and safety play, read The Policy Circle’s Brief Migration Between States.

Putting It Into Context

History

The Founding Fathers of the United States recognized the need to establish an orderly, peaceful nation as the cornerstone of civil society. To fully understand crime, we must first examine the relationship between the rule of law and the authority of law enforcement to provide and maintain order.

The legal framework for civil order is found in the U.S. Constitution, which secures and protects the rights of law-abiding citizens and consequences to those who operate outside of the law. Under the 10th Amendment of the Constitution, the federal government has limited powers, leaving the state governments to make and enforce laws for public health, welfare, and safety within their borders. State law enforcement agencies enforce state laws, while cities, counties, and municipalities are charged with enforcing laws at the local level.

By The Numbers

Understanding crime data is critical because crime trends influence policy and policing decisions, as well as decisions on an individual level. Traditionally, since the 1930s, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) has captured and provided national crime data through the Uniform Crime Reporting (UCR) Program with a report known as the Summary Reporting System (SRS). However, as of January 1, 2021, the UCR Program retired the SRS data collection system in favor of a new system: the National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS), which provides more detailed information on crimes, including circumstances and locations. Whereas the previous system only reported the number of incidents, NIBRS includes data on any and all reported offenses. For example, during an armed robbery, an assailant robs one person and kills another. Previously, only the most severe offense (i.e., homicide) would be recorded. The new system counts each offense (i.e., robbery, homicide) separately, which paints a clearer picture of crime in the U.S.

Crime Data Challenges

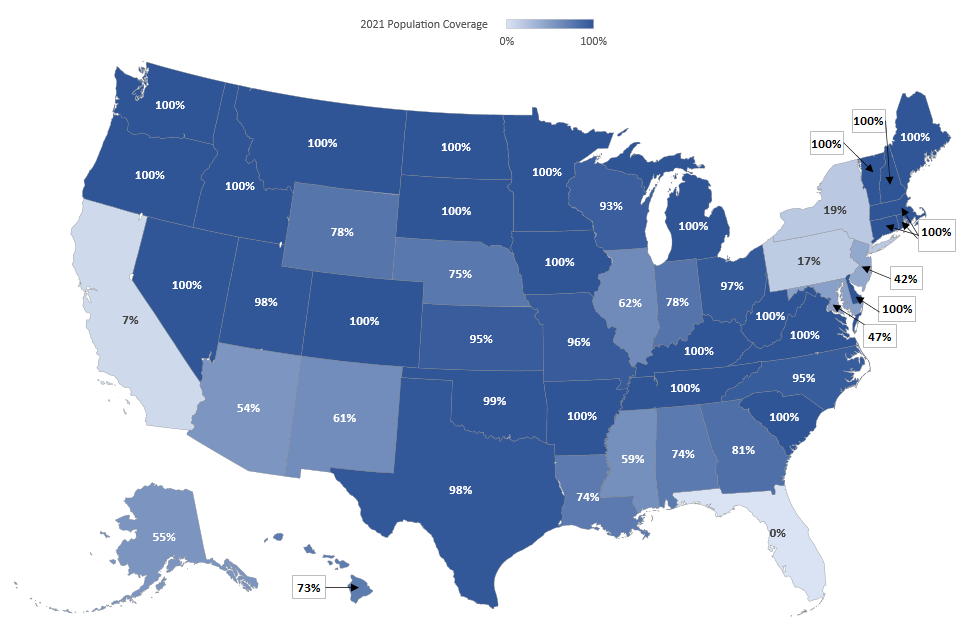

While in the long run, the NIBRS provides a much more detailed picture of crime and the surrounding data, there are major challenges in the current existing crime data, and the transition between new programs has painted an incomplete picture of crime today. Notably, a major challenge is the fact that reporting to NIBRS is voluntary at the federal level, and the FBI cannot compel reporting. Of the nearly 19,000 law enforcement agencies nationwide, 7,000 of them did not report their 2021 data to NIBRIS, including the NYPD, LAPD, and the entire state of Florida, compared to 85% of agencies who reported in 2020. Further, the shift from the SRS to the NIBRIS cost state and municipal governments millions of dollars. While the federal government provided significant aid to many law enforcement agencies, nearly 40% failed to submit their data.

The following graphic shows the percentage of law enforcement agencies in each state that fully reported their data to the FBI in 2021. Incomplete data means the FBI can only provide estimates. While the estimates may accurately reflect what we read about in the headlines, they are still an incomplete accounting of crime data. Accordingly, the FBI issued a disclaimer maintaining that the data cannot be used to decipher accurate trends or rankings of cities and states.

The recent and significant changes in how the FBI collects crime data will greatly impact accurate data points for years to come. “The result is that national crime estimates in the next few years will carry more uncertainty than ever before.”

Crime Data & Reporting

The Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) categorizes crimes as follows:

- Violent crimes: offenses that involve force or the threat of force (e.g., murder and nonnegligent manslaughter, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault);

- Property crimes: monetary in nature; do not use force against others (e.g., burglary, larceny-theft, motor vehicle theft, and arson).

Most states use similar classifications to categorize crime. To search for crime data reported by your state’s law enforcement agencies to the FBI, see the FBI’s Crime Data Explorer. To explore a particular law enforcement agency, see the Uniform Crime Report, maintained by private firm AH Datalytics.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS) is an agency within the Department of Justice whose primary goal is to gather, review, and disseminate information about crimes, criminals, and victims. The BJS publishes a yearly report called the National Criminal Victimage Survey (NCVS.) The report includes information on the victims of crime and not just the crime itself. According to the 2021 NCVS, less than half (45.6%) of violent crimes and 30.8% of property crimes were reported to authorities.

In addition to federal and state government entities, numerous organizations collect, analyze, and report crime data. For example, the non-partisan think tank Council on Criminal Justice publishes reports using available state and local crime data. The Major Cities Chiefs Association (MCCA), a professional organization of police executives in the largest cities in the U.S. and Canada, also collects and publishes violent crime reports, along with position papers, and other resources for police professionals.

Importantly, none of these data sources paint a full or timely picture because they rely on different (and often incomplete) data sources.

Local Crime Reporting

CompStat, short for Comparison Statistics, is one of many program management systems used by local police agencies nationwide to collect, measure, and analyze crime data. Developed by the NYPD in 1994, New York City was the first police department to implement this form of local tracking to provide police with the most exacting and powerful tools: information, transparency, and accountability.

Cities across the country rely on a variety of resources and tools to report crimes in their local communities. For example, The University of Chicago Crime Lab has been instrumental in supporting the Chicago Police Department by tracking crime and analyzing crime trends. For additional information, listen to The Policy Circle’s interview with the Founding Executive Director of the Chicago Crime Lab, Roseanna Ander here:

Cost of Crime

While currently presenting a challenge, the numbers surrounding crime are critical and directly impact policies and spending directed towards crime-control efforts. A November 2021 study estimated that the annual cost of crime in the United States is “$4.71-5.76 trillion including transfer from studies from victims to criminals and $2.86–$3.92 trillion net of transfers.” State and local governments spent $123 billion on police in 2019, which is approximately 3.7% of state and local general expenditures for operational costs (e.g., salaries and benefits).

The Role of Government

The Founding Fathers made it explicitly clear that the powers of the federal government and its role in criminal law are limited. In fact, the U.S. Constitution only mentions three federal crimes: treason, piracy, and counterfeiting. Congress passes legislation that defines the acts that constitute federal crimes, which are contained within Title 18 of the United States Code, and include “arson, use of chemical weapons, counterfeit and forgery, embezzlement, espionage, genocide, and kidnapping.”

The 10th Amendment of the Constitution provides that the “powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

A crime at the federal level must involve some type of federal interest or cross state lines. Examples include drug trafficking, crimes that take place on federal property, and crimes involving violations of immigration or tax law. Federal crimes are prosecuted by United States Attorneys in the federal criminal court system. Search for the U.S. Attorney assigned to your district by clicking here.

Some crimes fall under both state and federal jurisdiction. Still, the vast majority of criminal law exists at the state level, and most of the crimes we read about in the headlines, like homicides and assaults, are violations of state or local laws. Accordingly, responding to crime is primarily a function of state and local governments.

Just as the punishments for federal crimes are set by the federal government, state and local governments set the punishments for crimes committed within their jurisdictions. State law enforcement agencies are tasked with enforcing state laws, while cities, counties, and municipalities enforce the law at the local level.

Federal Legislation

During the mid-1990s, in American politics, both parties positioned themselves to appear “tough on crime,” adopting “top-down” approaches – more officers, more prosecutors, and stiffer penalties for crime deterrence. The Clinton administration enacted the largest and most comprehensive federal crime bill to date.

The 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act increased the number of prosecutors in high-crime areas, increased funding for states to hire new police officers and build prisons, created the Office on Violence Against Women, and established the Office of Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) to implement “community policing” practices.Part of the 1994 Act increased financial resources for local community law enforcement for a “bottom-up” approach to policing – getting officers out of police stations and vehicles and embedding them into the communities they serve.

Even with a nationwide decrease in crime rates, critics of the 1994 Act say it increased incarceration rates by mandating life sentences for repeat offenders, which included nonviolent offenses. Years later, President Clinton acknowledged that increased incarceration rates were an unintended and regrettable consequence of the bill.

Additional changes to infrastructure surrounding crime and law enforcement were seen in response to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. In 2007, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) created the Office for State and Local Law Enforcement (OSLLE) to act as a liaison between DHS and state, local, tribal, territorial, and campus law enforcement agencies across the country. The result was increased communication, training, and sharing of information between local law enforcement and the DHS in an effort to combat future terrorist attacks.

In more recent legislative efforts, in response to Covid-19, and in an attempt to provide financial relief to local governments, President Biden’s American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARPA) allocated $10 million for “policing and other public safety efforts” and $6.5 million for state and local communities. The U.S. Department of the Treasury issued guidance for the eligible use of these funds related to law enforcement, which included hiring, training, equipment, community policing programs, gun trafficking efforts, and mental health services, especially for crime victims.

According to The Marshall Project, “flexible” funding requests for funds issued out of the ARPA resulted in the inability of the federal government to specifically track how states and localities spent ARPA distributions on criminal justice measures or programs. You can find more about how your state or city spent their ARPA funds by searching here and see if the use of the funds met compliance and reporting requirements set out by the Department of the Treasury.

State & Local Policies

As outlined above, the 10th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution provides states the autonomy to govern themselves. The process to pass a law at the state level is similar to the process at the congressional level. Search and access your state’s laws and legal procedures with this resource guide.

Every state has the capacity to implement laws that reflect the values of its citizenry coupled with the responsibility to maintain a safe and orderly environment. State laws that address crime are no different and you can search for your state’s criminal code here.

Since states decide on the criminality of certain acts, they also create and implement laws regarding how to penalize citizens who break those laws. One of the most contested topics between states is capital punishment, i.e., the death penalty. Nearly half of the states have eliminated the death penalty, while others have modified the conditions by which that sentence might be suitable and the method by which it is carried out.

One important aspect of state and local laws is the continuous efforts of lawmakers and policymakers to adequately address the needs of the people they represent and serve. The scope of law and policy may be extensive and complex, but their purpose and responsibility is to provide a safe and orderly environment for each citizen.

Prosecution

A critical function of state and local level governments to address crime is found in the role of the prosecutor and prosecutions. According to the American Bar Association, a prosecutor is “an administrator of justice, a zealous advocate, and an officer of the court… [and] should exercise sound discretion and independent judgment in the performance of the prosecution function.” The function of prosecution and the indispensable role of prosecutors has a powerful impact on crime.

The top prosecutor in a locale, and one of the most defining members of a criminal justice system, is the District Attorney (DA). The DA may design and implement prosecution strategies to serve the needs of the governing administration, respond to public demand, or redesign how the office prosecutes criminal cases altogether, however they do not make laws. That remains a duty of the legislative branch.

In short, the DA has a considerable amount of discretion and can choose to prioritize which crimes are prosecuted and what sentences are administered. While criminal justice reform has long been subject to discourse, the prosecution’s discretion has recently sparked major debate and concern around the nation. Within this debate, some believe decriminalizing previously prosecutable offenses diminishes the values of civil society. In contrast, others believe decriminalizing certain nonviolent offenses, or not prosecuting petty crimes allows for more focus and resources to be allotted to more serious crimes.

According to reform-based efforts enacted through prosecutorial efforts, one assessment shares that some prosecutors are using their role to influence policy “aimed at lowering the transaction costs of criminal behavior while raising the transaction costs of criminal enforcement.”

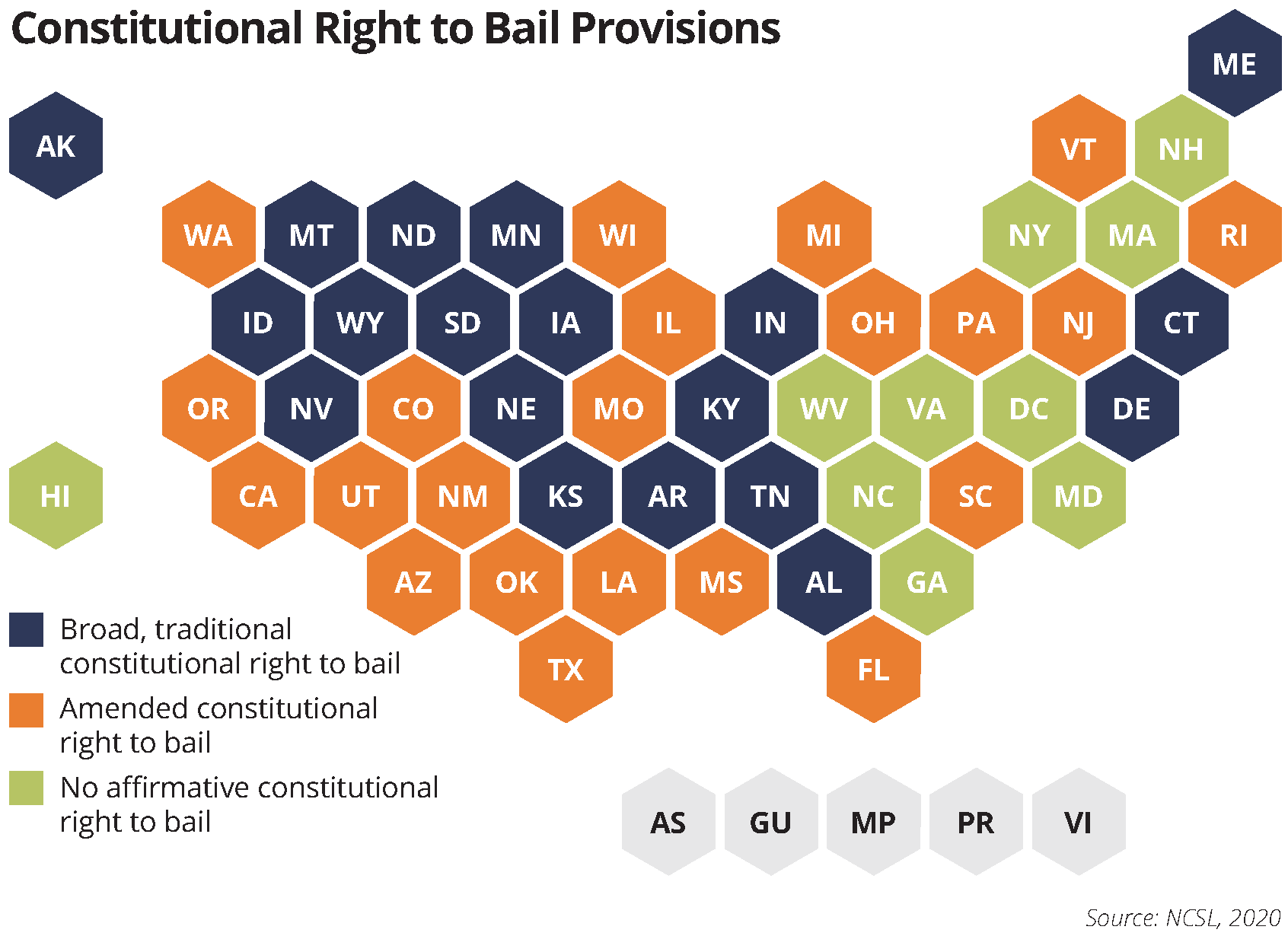

One highly debated aspect of prosecutorial policy is “pretrial release.” Originating from protections from “excessive bail” in the 8th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, the purpose is to release individuals from jail prior to trial once they agree to return to court. A judge decides whether an individual may be released, according to state laws, and determines the conditions of their release. For more information on your state’s pretrial release policy, look here.

Pretrial release does little to guarantee the individual will not commit a crime while released, as described in the events at the beginning of the Brief. The shooter, Hernandez, was granted permission to visit his newborn in the hospital even though a condition of his release was to wear an ankle monitor.

Punishment

An essential component of “justice” is whether the “punishment fits the crime.” An important tenet of our country’s values centers on liberty. Imposing on, or severely limiting, an accused person’s personal liberty is something our Founding Fathers considered a very serious issue and is continuously upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court. Arresting, jailing, or imprisoning someone accused directly imposes on a person’s civil liberties. The burden lies on the prosecution to prove a defendant committed the crime and receives appropriate punishment.

In the federal court system and in most states, the judge is solely responsible for imposing a sentence using the advisory guidelines and sentencing structures put in place by the legislature. Depending on a defendant’s criminal history and the specific crime at issue, judges may be bound by mandatory minimum sentencing imposed by statute or have wide discretion in structuring a sentence.

In fashioning a sentence, judges are left to balance several competing policy goals, including imposing a punishment that is proportionate to the crime, retribution for the victim(s), deterring the offender and others from committing the crime in the future, and protecting public order by incapacitating and (perhaps) rehabilitating the offender.

There is great debate about whether longer sentences actually deter people from committing future crimes and, thereby, benefit public safety. Analysis of a June 2022 study conducted by the United States Sentencing Commission indicates that longer sentences are highly effective in deterring crime, which is contrary to some prosecutorial strategies to impose lenient sentences even for violent crimes.

Compiling the data to adequately evaluate the effects of prosecution and punishment strategies on actual crime rates takes time. It is important to note that crime and prosecutorial strategies vary from city to city, as do the methods to reduce crime.

Current Challenges and Areas for Reform

Undoubtedly, the continuous news of crime rate increases, along with devastating stories of tragedy, deeply impact the everyday lives of Americans and the feeling of safety. Safety is a two-pronged concept: whether we feel safe, and whether we are, in fact, safe. One important aspect that contributes to not feeling safe is the perceived randomness of crime. As a civil society, we assume that there are “safe spaces”- schools, churches, grocery stores, etc., however, these spaces have been violated by violence in recent years. As we aim to better understand the challenges surrounding crime and areas for reform, it’s important to also look deeper into the crime that we hear about the most: mass violence and gun violence.

Current Challenges

Mass Violence

A 2022 study conducted by The Associated Press and Northeastern University examined databases and details surrounding mass violence between 2006 and August of 2022, and found that 2,742 victims had lost their lives in 526 mass killings in the United States. These horrifying acts include not only death by guns, but also by knives, fires, vehicles, and other weapons.

Gun Violence

Death by gun violence has continued to weigh heavily on the minds of Americans. The Gun Violence Archive (GVA) collects daily data from across the country and compiles it into tables and graphs by category and type of gun violence. In 2021, GVA reported approximately 20,985 gun violence deaths (excluding suicides), an increase of 7.4% from 2020, and 691 mass shootings, an uptick of 13.3% from 2020.

Mass shootings (a shooting incident that kills 4 or more people, not including the shooter) have increased in recent years. A study of mass shootings by The Violence Project (supported by the National Institute of Justice) from 1966 to 2019 found that 20% of mass shootings took place between 2015 and 2019, and more than half occurred since 2000. In 2022 alone, there have been at least 46 school shootings resulting in injury or death – the most since 2018 (as of November 2022).

The challenges of both mass violence and mass shootings have created and perpetuated a weakened feeling of safety amongst Americans with 53% of Americans sharing they worry about gun violence and safety every single day.

Policing

Understanding the role of police and the challenges in policing is critical in order to better understand crime and the current challenges to prevent increased crime. A review of the effectiveness of police presence found that time and locale-targeted police presence had a significant impact on crime reduction; meaning police departments that deployed police at specific times and in specific areas gleaned the most benefit to reduce or prevent crime.

The Manhattan Institute studied the recent rise in homicides in cities across the country and the correlation with “policing and criminal justice.” Many police departments across America experienced a decrease in police officers and recruiting over the last few years.

The Council on Criminal Justice reports police recruiting has not kept up with population increases, which puts a strain on local police departments.Even prior to the pandemic, the decrease in police officer recruiting and retention created a “workforce crisis” in law enforcement, forcing departments to examine the causes and create effective solutions. Fewer officers mean less manpower to cover considerable ground, longer response times for calls, and prioritizing some crimes over others. Naturally, this led to some upticks in crime because there were simply fewer officers available.

For more information about policing in America, watch The Policy Circle’s Move the Needle on Understanding Law Enforcement Brief.

Contributing Factors to Crime

Discussions about what leads to crime and possible solutions sometimes leads to contentious debate, as demonstrated in the Honesty with Bari Weiss podcast conversation between two thought leaders, Lara Bazelon and Rafael Mangual, on the subject. Even with a robust disagreement, a few elements relating to crime are readily agreed upon.

Disinvestment. When business and industry leave an area, jobs and local financial investment go with them. Some Chicago neighborhoods have experienced the effects of disinvestment for decades. The Brookings Institution provides an in-depth examination of the relationship between divested neighborhoods and gun homicides.

Urban centers. Highly-populated areas that experience significant income inequality, unemployment, low educational attainment, and poverty are more heavily steeped in crime.

Educational attainment. Studies show a correlation between exposure to violence at a young age and indicate that decreased educational attainment (i.e., high school diploma, an equivalent, or the highest grade reached) may subsequently lead to criminal behavior. Alternatively, higher educational attainment directly impacts future employment opportunities and earning potential. The theory is that achieving a higher level of education enhances earning potential, which diminishes the need to engage in criminal behavior. Communities rife with low education attainment, high unemployment, and other socio-economic factors tend to be more consistently subject to pervasive crime.

Areas of Reform

Understanding crime rates and how they relate to our safety is the first step to taking action. As Stand Together Trust fellow Vikrant Reddy shared in The Policy Circle Crime and Safety panel, “We’ve stumbled upon this really bizarre model where we let people get away with stuff over and over and over again, then when we finally do decide to catch and prosecute, the sentences can be very, very long. So what you have is this system that is more focused on the punishment than it is on the prevention. I think that fundamentally the strategy that works is to pour more of the resources into prevention than into punishment. “

Although this overview alone cannot cover every possible solution to reduce and prevent crime, there are a few to consider and possibly explore.

Role of the Private Sector

The private sector can contribute to the “bottom-up” approach to help address one of the contributing factors that lead to crime – lack of economic opportunity. Businesses create jobs in the areas they operate, drawing consumers to their business, and potentially attracting other businesses as well. This generates tax revenue which can be used to further support community development and reinforce local infrastructure, including safety programs, affordable housing, youth development initiatives, workforce programs, area clean-up, and refurbishing public spaces.

Small, localized investments contribute to addressing symptoms of crime by creating economic opportunity. Though these efforts do not overtly address overarching or systemic factors that impact the relationship between high-risk areas and crime, providing economic investment in a community certainly helps move the needle in that direction.

Government Agency Coordination

Federal and state government agencies responsible for the safety and well-being of the citizens they serve play a crucial role in combating crime. The role of federal, state, and local governments should be to create cooperation between agencies and develop collaborative initiatives that address the various aspects of crime and support solutions to crime that are driven from within communities.

Education & Workforce Development Programs for Offenders

Nearly all of the 2.2 million incarcerated individuals will be released from prison at some point, and 4 in 10 are reincarcerated again within 3 years. The Second Chance Act (SCA), passed in 2008, grants federal funds for strategies to support individuals recently released from prison with services and support programs to reduce recidivism and improve reentry into society.

Provided under the SCA, Correctional Adult Reentry Education, Employment, and Recidivism Reduction  Strategies Program (CAREERRS) recipients use SCA funds for education and employment services to help individuals obtain a high school diploma (or an equivalent), and address employment challenges as a result of incarceration. The National Institute of Corrections indicates that previously incarcerated individuals who participate in “Offender Workforce Development” are 33% less likely to be re-incarcerated.

Strategies Program (CAREERRS) recipients use SCA funds for education and employment services to help individuals obtain a high school diploma (or an equivalent), and address employment challenges as a result of incarceration. The National Institute of Corrections indicates that previously incarcerated individuals who participate in “Offender Workforce Development” are 33% less likely to be re-incarcerated.

Youth Employment Programs

Summer employment programs for youths and young adults (typically aged 14-24) provide pre-employment training (e.g., work readiness, teamwork, conflict resolution), on-the-job skills, wages, and exposure to various businesses and industries. Employers register with the governmental agency administering the program, youths and young adults register to participate (participant numbers are limited according to the program), and the administrator connects the two.

Mental Health

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), people with mental health issues comprise a large portion of the incarcerated population:

- About 2 million people with serious mental illness are booked into jails annually;

- 66% of women in prison have a history of mental illness;

- 70% of the youth in the juvenile justice system have a diagnosable mental health condition; and

- Of those already incarcerated, approximately 37% of people in state and federal prisons, and 44% of people in local jails have had a history of mental illness

Mental health has become more and more a focal point of policy leaders to better understand the citizens they serve and the sects of the population that are disproportionately affected by crime. According to NAMI, in order to combat growing mental illness, and reduce the number of mental health crises leading to crime and incarceration, policies must be set to not only create more accessible mental health resources but also invest in crisis response systems and reduce the role of law enforcement in mental health crises not affiliated with crimes.

On the local level, Seattle’s Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD), is a program used by police to intervene before a crime is committed. According to the National Institute of Justice, LEAD is “a pre-booking, community-based diversion program designed to divert those suspected of low-level drug and prostitution offenses away from jail and prosecution and into case management and other supportive services.” After enrollment in the LEAD program, 58% of participants were less likely to be arrested and due to its success, LEAD has been adopted by various law enforcement agencies nationwide.

To learn more, explore The Policy Circle’s Brief on Mental Health.

Criminal Justice Reform

Although the issues surrounding crime and safety are complex and heavily debated, the need for transformation surrounding criminal justice and incarceration is one that many agree is necessary. With increasingly higher numbers of American adults in prison, jail, or on probation or parole, the role of government continues to significantly expand to meet these needs. With initial reform efforts to improve the criminal justice system, reduce recidivism, and begin to reduce excessive sentencing for nonviolent offenders, a more balanced and limited role of government can be achieved.

Conclusion

Crime and safety are inextricably linked. This overview outlined the challenges in collecting and understanding crime data and provided resources to find the actual crime rates for our communities. Accessing real crime data and understanding the factors that various contribute to crime can help us better understand the complex task of addressing it, which impacts our sense of safety, as well as how safe we actually are.

“Solving” the issue of crime requires a multi-pronged, multi-service approach and should ultimately be addressed within the communities most adversely affected by crime along with the governmental agencies tasked with the safety of each citizen.

Ways to Get Involved & What You Can Do

Measure: Better understand and find out more about the crime data in your state and district and explore the latest with the FBI’s Crime data Explorer system.

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Who is your District Attorney? Are they appointed by the President? What are their priorities? Discover more with this resource here.

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Discover more about the prosecutor in your district, and foster collaborative relationships with law enforcement, first responders, faith-based organizations, local hospitals, community organizations, school boards, and local businesses.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team at communications@thepolicycircle.org, for connections to the broader network, advice, and insights on how to build rapport with policymakers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Discover and support local organizations focused on community revitalization

- Reach out and connect to local community members focused on educational and employment opportunities

- Volunteer with local organizations that focus on crime prevention pathways in your community

- Explore mentorship opportunities in community centers and local organizations

- Report any suspicious activity or crimes in your communities to improve the existing crime data

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.