Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this Policy Circle Brief

Case Study

In 2016, at the age of 54, world-renowned mountain climber Conrad Anker suffered a heart attack while attempting to summit the tallest unclimbed mountain in Nepal. At an elevation of 20,000 feet, Anker had to rappel and hike down the mountain before he could be helicoptered to a hospital in Kathmandu for surgery.

Now, although Anker still climbs, he acknowledges “the heart is the one muscle that can’t fail. So, it’s about realizing where you are in life and knowing your limits”. As Vice President of the Khumbu Climbing Center at the base of Everest, which trains Sherpas and climbers, he hopes to serve as a mentor for future climbers. In the movie Religion of Sports: Hold Fast, Anker climbs El Capitan in Yosemite with his mentee, Alex, a cancer survivor. “One way to give back in retirement is to share your talents and skills with people,” Anker says.

For Anker, that thought comes naturally and is influenced by his time in Nepal, where aging and death are just part of life. Everyone accepts this, and the idea of staying forever young is a foreign concept. Elders are respected and play an important role in families and society. Multiple generations live together and support each other, and this family support is valued almost more than any kind of financial support. This may be at odds with how many people view aging in the United States. As Anker asks, “What does it say about our culture when Forever21 is a celebrated brand?” Is it possible to alter the cultural view of aging?

What is Aging?

Aren’t we forever young? If 50 is the new 40, when do we actually become part of the “elderly” population? There are 65-year-olds who can no longer drive, but also 90-year-olds who still enjoy skiing. Stanford psychologist Laura Carstensen tried a new description for people over 65: perennials, like the plants that blossom “again and again” if given proper care and support.

Forbes contributor Howard Gleckman has a different point of view. As he says, “Words do matter, and I fear that hiding behind bland descriptions like “perennials” is just another form of denial. As long as we think of ourselves as immortal (which perennial implies), we’ll have even less reason to plan emotionally, financially, and physically, for the near-inevitability of age-related limitations.”

Why it Matters

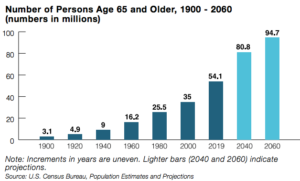

In 1950, life expectancy in the United States was 65.6 years for males and 71.1 years for females. As of 2021 (the latest CDC report as of 2023), it was 73.5 years for males and 79.3 years for females. According to The Administration for Community Living, 17% of Americans were over the age of 65 in 2020; by 2040, that number is expected to grow to 22% of Americans. The size of this population will impact all areas of life, from society and the economy to politics and health care.

Putting it in Context

The Economics of Aging: A New Workforce and New Customers

People are healthier and living longer, and due to years of stagnant real wages and the overall economic shift to less labor-intensive occupations, more people are working longer. In a report published in November 2022, 18.9% of adults over age 65 were working or looking for work in 2021, compared to 10% in 1985. Additionally, as shared in the November 2022 report, the rate of new entrepreneurs in the United States was highest among the 45-54 year age group, reaching 0.44% in 2021 and 0.37% for the 55-64 year age group.

Many suggest that the pandemic and inflation have harmed the financial prospects of older Americans. American workers over age 55 have seen the slowest employment recovery since the pandemic began, and are still years away from being eligible for Medicare, even though they may have lost health insurance provided by their employer. The ability to begin collecting Social Security early at age 62 provides a financial lifeline to older Americans who lost their jobs, but also means fewer years of building up retirement savings and a lower level of monthly benefits. Inflation has led many Americans to delay their retirement plans and contributed to “unretirement,” with older Americans returning to the labor force.

A workforce of older adults can provide institutional wisdom and training, and many organizations are tapping this knowledge by better accommodating older workers. For example, automaker BMW redesigned its production facilities to better accommodate older workers. Simple changes such as softer floors, larger fonts on computers, and ergonomic seating increased productivity and decreased absenteeism.

However, numerous lawsuits regarding the Age Discrimination in Employment Act may imply employers see older workers as a disadvantage. According to an Urban Institute study, over half of the surveyed full-time, full-year workers (ages 51 to 54) experienced “employer-related involuntary job separation.”

Employers must also come to terms with the fact that an aging population entails serving aging customers and their unique demands. The market for the generation of older adults is worth over $9 trillion in the United States alone and is projected to grow through 2050. In order to capitalize on this market, companies and organizations may need to reshape their business strategies. The MIT AgeLab was established specifically for this purpose and works with businesses, government, and other organizations to innovate product designs, restructure policies, and change how services are delivered to better serve an aging population.

Aging 2.0 is another company that works to create a network of innovators that serve individuals ages 50 and older, and also helps aging-focused startups, particularly in the areas of caregiving, healthcare technologies, and artificial intelligence. Addressing the needs of older Americans through AI research and entrepreneurship has resulted in advancements that help both patients and clinicians, such as wearable smart devices that track biometric data to assist with daily living at home. Still, there is room for more growth in this industry as technology startups aimed at people age 65 and older have seen a recent decrease in investment funding.

An Aging Society: Housing and Community Design

Another concern for the aging population is living arrangements. Private options outside of one’s own home include “Senior Only” complexes, such as retirement communities, and assisted living facilities. Many of these facilities are nonprofit organizations and can request 501(c)(3) status as elderly housing organizations. Approximately more than 810,000 Americans live in assisted living communities, and there are almost 5,000 continuing care communities and 26,000 businesses that provide living services for seniors. Public housing assistance for low-income seniors is also provided by the government in the form of reverse mortgages, Section 8 housing vouchers, and home repair or modification assistance loans.

Some areas for local communities to consider when planning for aging citizens include education, housing, mental and physical health, recreation, and transportation. For example, the city of Irvine, California, involved 600 residents in developing a Strategic Plan for Seniors and created a Senior Citizens Council Meeting. Wichita, Kansas, and Findlay, Ohio, are now home to parks and pickleball courts specifically designed for seniors. Five programs in Oklahoma provide social, emotional, and academic benefits to children and seniors by using rooms in retirement homes as Pre-K classrooms during the week.

The communities in which senior citizens live have proven to be accurate predictors of their physical and mental health. Residents of more affluent communities have a life expectancy of 87 years, tend to have high levels of cognitive function and lower levels of obesity. Those from more economically disadvantaged areas, such as Native American reservations, have life expectancies closer to 70 years and tend to have chronic health issues, and negatively self-rate their health status.

Individual buildings can also better serve older adults. Geriatrician Louis Aronson calls architecture designed specifically for the needs of an aging population “silver.” A “silver” building would be “well-lit, quiet, accessible, and safe. It would be spacious enough to accommodate walkers and wheelchairs and provide room for a caregiver.” Although simple ideas, these elements are not widely incorporated in assisted living facilities or senior communities. Ideas like Aronson’s can help not only accommodate mobility and accessibility issues but also maximize independence and quality of life for older adults.

Aging and Poverty

Financial security for an aging population is of the utmost importance, but many aging Americans spend what should be the golden years in poverty. As of 2023, the most recent data states that in 2020, approximately 9% of people aged 65 and older (5 million individuals) lived below the Federal Poverty Level. A second measurement, the Supplemental Poverty Measure (SPM), accounts for regional variations in costs (such as for housing) as well as non-cash benefits (such as SNAP); based on this measurement, just under 10% of persons age 65 and older lived in poverty in 2020. Women aged 65 and older had a higher poverty rate (10.1%) than men (7.6%).

In one PEW research survey, half of working adults said they had enough money to retire comfortably. The latest available reported median income as of 2023, for those age 65 and older was $26,668 in 2020, which decreased from $27,398 in 2019. Most low-income men and women are likely to live just on social security benefits, where the average benefit is about $21,384 annually.

Role of Government

Federal Role

The Older Americans Act created the Administration on Aging (AOA), a separate agency under the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The AOA has developed a network of national aging services that consists of 56 State Units on Aging and 655 Area Agencies on Aging. Funding for the state and area agencies is based on the number of residents over the age of 60. The AOA also works with and helps to fund services for elders, including the Eldercare Locator, the National Institute of Aging for aging research, the National Council on Aging, and the National Center on Elder Abuse, among others. In Congress, the Senate Special Committee on Aging does not have legislative jurisdiction but studies and publishes material on aging-related issues, makes recommendations to Congress, and holds hearings on financial security, fraud, and wellness. The FY 2023 AOA budget, which is $2.378 billion, is divided into four main categories:

- Nutrition: $1.138 billion

- Transportation: $295 million

- Recreation: $135 million

- In-home care and adult day care: $798 million

To see additional funding and budget allocation visit the Administration for Community Living’s report here.

State Role

State Units on Aging (SUAs) are designated by state legislatures and administer the Older Americans Act in their area. Each state organizes how its aging department functions based on the needs of the state. State units divide federal funds among area agencies and coordinate and oversee services offered by area agencies. Some states also have their own senate committees on aging and offer state-specific resources for residents.

Local Role

Area Agencies on Aging (AAA) are “local leaders on aging” that work on “planning, developing, funding and implementing local systems of coordinated home and community-based service.” AAA’s can be a city, county, government council, or regional planning commission designated by an elected official, as well as a public or nonprofit private agency. These agencies offer health and wellness programs, financial assistance, transportation services, educational opportunities, and nutrition programs. Many of these services are provided through Senior Citizen Centers, which serve as community centers where agencies can interact with senior citizens and understand their needs.

Community Services

The Older Americans Act (OAA) provides social services and programs for individuals over 60 and their families to provide extra support. Through state and local agencies, the act provides nutrition services, support for family caregivers, community service employment opportunities, services to prevent abuse and neglect, and access to programs like Medicaid. Additionally, the National Minority Aging Organizations Technical Assistance Centers and the National Resource Centers on Native American Elders provide services that target economically disadvantaged groups.

Medicare and Medicaid

Medicare is a federal insurance program that primarily serves people age 65 and older, as well as disabled people and dialysis patients, regardless of age or income. It is run by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), a federal government agency that is part of the Department of Health and Human Services. Medicare State Health Insurance Assistance Program (SHIP) provides local insurance counseling and assistance for Medicare beneficiaries. There are over 3,300 local SHIPS that offer services regarding coverage options, fraud, and billing problems. Despite the fact that more than 28 million Medicare beneficiaries are in a Medicare Advantage plan, its spending cuts have been debated.

Medicaid is a federal-state assistance program that serves low-income Americans regardless of age. Medicaid is run by state and local governments; there is a set of general federal guidelines to follow, but options (such as waivers) vary from state to state.

Social Security and Pensions

Social Security provides a basic monthly income for older workers and their families and is financed with payroll taxes. As of March 2022, over 65 million people received Social Security benefits; older Americans made up about 80% of beneficiaries. As the population of adults eligible for Social Security increases, the system, which is already spending more than it takes in, will be placed under more strain. By 2037, “the trust fund reserves are projected to become exhausted,” and taxes will only cover about 75 percent of scheduled benefits.

For those with limited income over age 65 or those who are disabled or blind, Social Security administers Supplemental Security Income (SSI). Unlike Social Security, SSI is not based on work history. SSI also covers health costs and provides eligibility for food assistance. Women have a higher risk than men of having low income and needing to rely on Supplemental Security Income; as women are often employed in lower-paying jobs and more likely to interrupt work to care for children, they accrue less income over time.

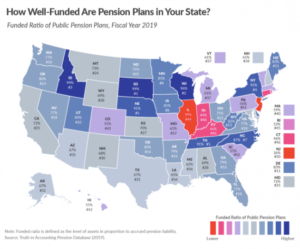

Another group of the population facing challenges is public sector employees. AARP estimates that 90% of workers in the United States are covered by Social Security, but close to 21 million current and former public sector employees, such as teachers and firefighters, are covered by local- or state-funded pension plans. In 2021, there were 296 states and 4,632 local public pension systems. In most of these pension plans, a share of the employee’s salary goes to a pool of funds that is invested on behalf of the employee and will be repaid in retirement, meaning that public pension funding comes mostly from investment earnings.

Like Social Security, public pension plans are running a deficit due to over-promising the value of benefits. The assumed rates of return used by most statewide retirement systems are much higher than actual earnings on investments. Although each state has its own funds, the total national public pension funding shortfall was $1.49 trillion at the end of 2020, but positive market performance has helped shrink the deficit; by the end of 2021, total unfunded state pension obligations were less than $800 billion, the most well-funded they’ve been since 2008.

According to information released in November of 2022 by the Pension Rights Center, the median income from state or local government pensions was about $22,860 in 2021. For a federal government pension, it was just over $26,734, but federal employees have a different plan called the Federal Employees Retirement System (FERS), which is not directly affected by the state public pension crisis.

See how well-funded your state’s public pension plans are.

Challenges and Areas for Reform

Address Fraud

Addressing the needs of senior citizens also involve taking steps to ensure adequate protection for this population. Senior citizens are frequently the target of scams and fraud, the most common of which are related to healthcare, investment, and – because older Americans are more likely to own homes – homeowner and reverse mortgage fraud. Such scams can have crippling financial effects; according to a report by Bloomberg, scammers financially exploit as many as 5 million older Americans every year, resulting in losses of over $30 billion.

Individual seniors are not the only ones affected by scams. In April of 2019, federal authorities charged over twenty people involved in a coordinated Medicare scam that “peddled unneeded orthopedic braces to hundreds of thousands of seniors.” Medicare beneficiaries are affected because their private information in the hands of fraudsters can be resold for other illegal purposes. Additionally, the entire Medicare program’s loss due to the fraud is estimated at $60 billion.

In 2018, 36 states, Puerto Rico and the District of Columbia addressed fraud against senior citizens, and 24 states enacted legislation. Moreover, according to the FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center, elder fraud cost Americans over the age of 60 more than $966 million in 2020. The Elder Abuse Prevention and Prosecution Act of 2017 added a national level of prevention to support the efforts of the states. Many government officials have also called on the FCC and FTC to do more to work with telecom companies for protection from fraud.

Fight Disease

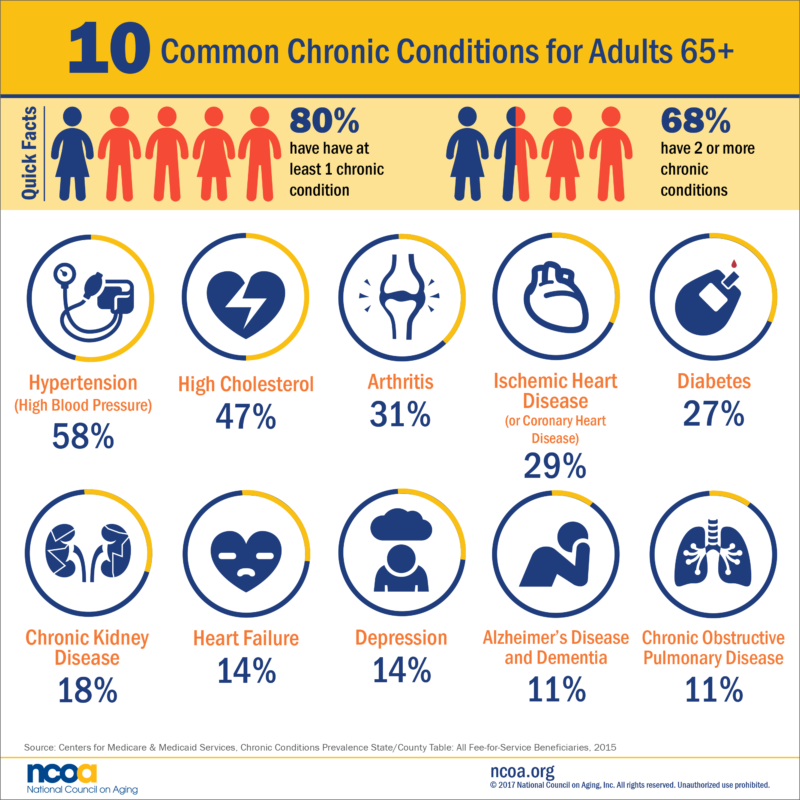

According to the National Council on Aging, 4 out of 5 adults over age 65 have at least one chronic condition, and over ⅔ have two or more chronic conditions. The CHRONIC Care Act, a provision to extend care for chronic conditions, passed the Senate with bipartisan support in September 2017. The act extends provisions for independent care at home and supplemental benefits to meet the needs of chronically ill Medicare Advantage enrollees.

One chronic condition is dementia. In the United States, 5.7 million people live with dementia, and families bear 70 percent of dementia care costs through unpaid caregiving and out-of-pocket expenses. In January 2019, the Building Our Largest Dementia (BOLD) Infrastructure for Alzheimer’s Act (P.L. 115-406) was signed into law. It will create a national public health infrastructure to implement effective Alzheimer’s interventions, focusing on diagnostic practices, preventative measures, and funding for public education, data analysis, and technical assistance to public health officials and healthcare professionals.

Ensure Financial Security

Make Saving for Retirement Easier

Prior to the coronavirus pandemic, about 35% of workers in the private sector did not have a defined contribution or benefit plan from their employer. Employers are noticing. A growing number of employers are making efforts to help workers with savings accounts, “reflecting concern over the impact money problems are having on productivity levels and workers’ ability to retire.”

Their efforts are supported by legislation. The SECURE Act, signed into law in December 2019, “is the most sweeping retirement bill in more than a decade,” according to American Century Investments. The bill changed the required distribution age, eliminated age limits for IRA contributions, and expanded employer plans to certain part-time employees, among other changes. At the state level, twelve states, now including Pennsylvania and Hawaii, have auto-IRA accounts that encourage workers to save for retirement.

Making saving easier is particularly important in light of the coronavirus pandemic. The CARES Act allowed people under the age of 59.5 affected by the coronavirus to take a distribution of up to $100,000 from an IRA or 401(k) without penalty. A survey from Kiplinger and digital wealth management company Personal Capital found almost 60% of Americans withdrew or borrowed money from an IRA or 401(k) in 2020. Axios explains, “Most U.S. retirement accounts were underfunded already, and the survey shows that the pandemic caused a significant number of Americans to pull money out, potentially setting them back even further.” More than half of those who withdrew money said they planned to work longer or delay their retirement.

Get Social Security on Sound Financial Footing

In 2022, 19.4% of federal government spending went to Social Security. Yet, projections show that Social Security will no longer be able to pay full benefits starting between 2034 and 2037. Options to prevent fund depletion include increasing the share of wages subject to payroll tax, cutting benefits, or raising the retirement age to reduce the number of years people receive benefits. For example, an immediate benefit reduction of 13% or an increase in payroll tax rate from 12.4% to 14.4% would allow for full Social Security benefit payments for 75 years. According to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, Social Security will run cash deficits of $2.8 trillion over the next decade, and the program will be insolvent by 2034. Both Social Security and Medicare programs will be responsible for nearly 80% of the deficit’s rise between 2023 and 2032, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

Provide for Caregivers

Palliative Care

The World Health Organization defines palliative care as “an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing…life-threatening illness.” This includes providing pain and symptom relief, integrating psychological and spiritual aspects of care, and offering a support system for patients and families. According to Dr. Diane Meier at the Center to Advance Palliative Care, the goal is to lessen the suffering of people who have serious illnesses so they can live in dignity. This is not the same as hospice, which refers to care for terminally ill patients with a life expectancy of less than six months.

There are few educational opportunities that explain what one should expect when hit with a serious illness or how to navigate the healthcare system. Organizations such as the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CACP) work to reduce this knowledge gap by providing information, resources, and webinars and by creating Wikipedia pages that point to options in care.

Insurance Coverage

Until a few years ago, Medicare, Medicaid, and most private health insurers only provided palliative care services for patients in hospice care or in the hospital. Because of this, people misunderstood palliative care and hospice care to be the same thing. Medicare now covers advanced care planning provided by medical professionals to help patients learn about health care options and determine the best options for their wants and needs.

With this change in Medicare coverage, payment methods may need to be restructured in order for clinicians to better manage care measures. Alternative Payment Models (APMs) are approaches offered by the Quality Payment Program from the Department of Health and Human Services. APMs give “added incentive payments” and are based on the performance of services provided to Medicare patients.

Family Caregiving

There is also the issue of compensation for family caregivers. One AARP study found that care provided by millions of unpaid family caregivers across the U.S. was valued at $600 billion in 2021. Another AARP Study found that about 41.8 million Americans served as unpaid family caregivers to an adult over 50 in 2020, up from 34.2 million in 2015. The average caregiver provides almost 24 hours of care per week. Family caregivers also note financial impacts; almost 30% of respondents said they had stopped saving, and 22% said they had used up personal short-term savings. About 11% of caregivers indicated they had to start working, work more, or pick up a second job to cover financial caregiving impacts.

Employment impacts are common among family caregivers as well. Six in ten categories reported having to go to work late, leave early, take time off, reduce hours, or take a leave of absence.

The Family and Medical Leave Act allows eligible employees 12 work weeks of leave in a twelve-month period. Approximately 60% of US workers meet the law’s eligibility requirements. About 53% of family caregivers said they had unpaid family leave, and 39% said their employers offered paid family leave, although only 26% said their employer offered employee assistance programs.

A number of bills have been introduced to address family caregiving. Such credits could make up for some of the lost income and lost Social Security benefits when working family caregivers decrease their hours or leave the workforce to provide care. Proposals for Social Security caregiver credits have bipartisan support and have been introduced in every Congress since 2001, but have never advanced out of committee due to concerns about financing and preventing abuse of credits.

Promote Education Initiatives

Medical Professionals

Training for medical professionals was designed in the seventies and has not evolved to account for people living longer with chronic illnesses. Doctors are often not trained to explain treatment options, the paths ahead, or advanced care planning such as palliative care, nor are they compensated for doing so. Dr. Meier notes that there is no federal standard for medical education regarding caring for older adults, although there is a movement to change this. The Palliative Care and Hospice Education and Training Act, which was backed by the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, the Hospice Action Network, and the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization, among others, promotes palliative care research, education, and training. The bill was passed by the House in January 2020 but did not make it through the Senate.

Citizens

The Council for Economic Education has developed National Standards for Financial Literacy, a framework for teaching personal finance in schools, as many people do not fully recognize how harmful it is to borrow against their retirement savings to pay bills. Others, especially younger Americans, have difficulty budgeting and saving for retirement due to the costs of debt and everyday expenses. Per the Council for Economic Education’s 2020 Survey of the States, 21 states require high school students to take a course in personal finance, and 25 states require high school students to take an economics course. For more, see The Policy Circle’s Financial Literacy Brief.

Conclusion

Staying physically active and cognitively engaged while planning for age-related limitations, and having local family support and connections with the community are key efforts to retaining a sense of purpose throughout life. Changing the culture to embrace aging as a part of life and incentivizing planning for the future can help policymakers and individuals incorporate aging into their decision-making process, whether it relates to employment, community planning, education of healthcare professionals, or product and service development.

What You Can Do/Ways to Get Involved

Measure: Find out what your state and district are doing about the aging population.

- Do you know the demographics in your community or state? How much of the population is over the age of 65?

- What legislation has there been in your state related to aging, community planning, healthcare, or pensions?

- Is there a task force or project in your state or community, or does one need to be formed?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Who oversees your state’s aging units or the agencies on aging in your area?

- What organizations exist in your area?

- Find your state’s AARP office

- Does a higher education institution in your state have a program, similar to MIT’s AgeLab?

- What steps have your state’s or community’s elected and appointed officials taken?

- Does one of your legislators serve on the Senate Special Committee on Aging?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with first responders, faith-based organizations, local hospitals, community organizations, school boards, or local businesses.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, communications@thepolicycircle.org, for connections to the broader network, advice, and insights on how to build rapport with policymakers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Learn about the policies put in place by your state’s unit on aging and your area’s agency on aging to understand the needs of your state and community, existing programs, and how these are funded.

- Investigate the state pension funding gap, and see how well your state is doing.

- Talk to your elected officials to determine what is being done about important issues affecting seniors, such as fraud protection measures.

- Take a walk around your community and consider how housing, recreation, and transportation for seniors have been incorporated into city planning.

- Consider the workforce in your community. Does the workforce in your place of employment include adults over 65? How does your work serve aging customers?

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.

Thought Leaders & Additional Resources

Government Agencies

Legislators

Organizations

The Cost of Aging

- Wharton University of Pennsylvania: The Time Bomb Inside Public Pension Plans

- The George Washington University Milken Institute School of Public Health: Study on the Growing Cost of Aging in America

- NIH Operating Plan: National Institute on Aging

Society

- Stanford Medicine’s Longevity: The Benefits and Burdens of an Aging Society

- National Institute on Aging: Aging Well in the 21st Century

- USAging: Policy Priorities

Economy

- Justice in Aging: Older Women and Poverty

- WSJ: How Aging Japan Defied Demographics and Turned Around its Economy

- PEW: When Do Americans Plan to Retire

Care

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.