This brief dives into the basics of campaign finance, specifically the key terminology and debates surrounding campaign spending; the types of political organizations that raise and spend money in the political process; laws and court cases that have shaped campaign finance; and helpful information to know before you donate.

Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

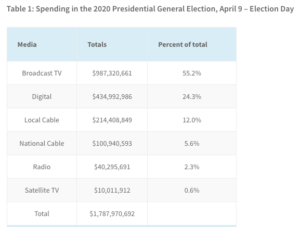

The main purposes of campaign spending are to generate name recognition and reach potential voters with a candidate’s message. Like any enterprise, political campaigns need resources to fund the activities that will help get the candidate elected. The amounts vary greatly, depending on the type of race, whether the race is contested, whether it is national, state, or local, and the costs of media (i.e., buying airtime) in the market.

For more on elections and election basics, see The Policy Circle’s Election Processes & Innovations Brief.

Why it Matters

Free Speech

Participating in fair and open elections is one of the many freedoms Americans enjoy. The First Amendment ensures your right of free speech and it is an expression of this right to contribute directly to a candidate’s campaign, or to make an online video or TV advertisement in support of or opposition to a candidate. In addition to voting, this is how you can make your voice heard. Government is always going to have a position of power, and so free speech in the form of support of or opposition to elected officials serves as an important check on that power. Free and fair elections should maximize people’s ability to run and participate and support candidates. Setting strict limitations and regulations on campaign financing can squelch that participation.

Corruption

Some argue that large contributions make politicians reliant on wealthy individuals or corporations, so they then answer to these donors and contributors instead of the average voter. For example, many point to“the magnitude of quid pro quo corruption in the Nixon White House,” for strict campaign finance laws.

The goal is a light hand that controls corruption while allowing the American people to speak out for what they believe in.

This PBS Crash Course video provides an overview of campaigns and the reasons they are so expensive (9 min):

Money in Politics

Uses

Uses

Campaigns use money to pay consulting fees and salary to political advisors and campaign staff; for travel, events, supplies/equipment, research/polling, and office space; and for political advertising. The political advertising machine is large, from those who direct the strategy to those who make the ads and others who purchase airtime in the target media markets. This includes digital advertising as well as direct mail.

Money is spent differently depending on the type of organization, the activities they are allowed to engage in, and any relevant laws. Hard money goes directly to candidates and is tightly limited by campaign finance laws. The limitations make it hard to raise, but few restrictions make it easy to spend. Soft money cannot go directly to a candidate or a campaign, and can only be used for “‘party-building activities,’ such as advocating the passage of a law and voter registration, and not for advocating a particular candidate in an election.” However, contributions can be unlimited.

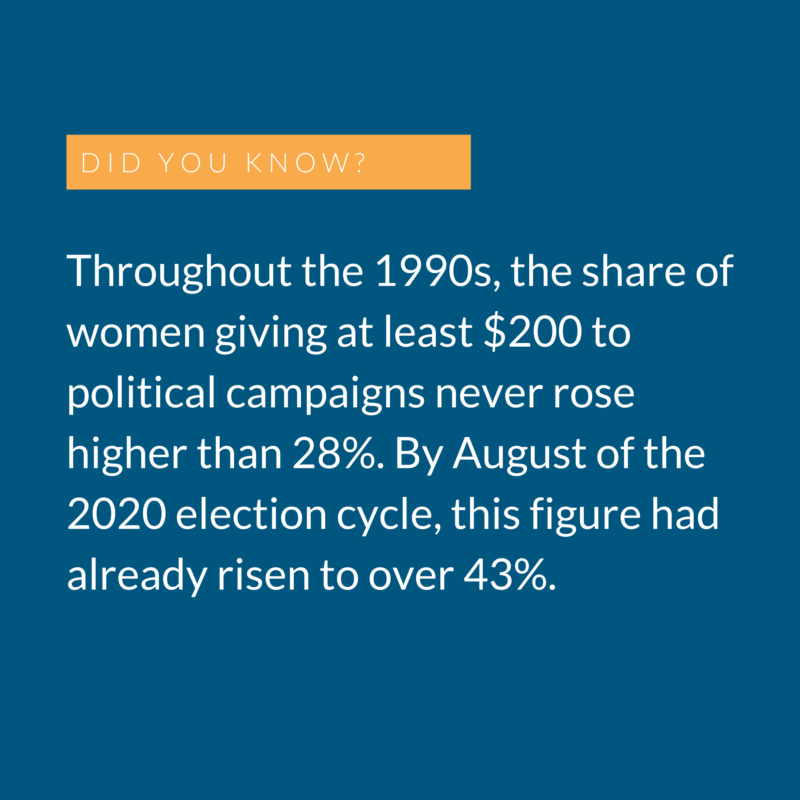

Donors

The Institute for Free Speech notes, “Foreign nationals, national banks, and Congressionally chartered corporations (like Fannie Mae) may not make contributions in any elections – federal, state, or local. Corporations and unions are prohibited from contributing in some states, and certain kinds of corporations, such as public utilities, gaming and liquor licensees, and insurance companies may face special restrictions. Lawmakers have also proposed restrictions on contributions made by donors residing outside a candidate’s state.”

The Institute for Free Speech notes, “Foreign nationals, national banks, and Congressionally chartered corporations (like Fannie Mae) may not make contributions in any elections – federal, state, or local. Corporations and unions are prohibited from contributing in some states, and certain kinds of corporations, such as public utilities, gaming and liquor licensees, and insurance companies may face special restrictions. Lawmakers have also proposed restrictions on contributions made by donors residing outside a candidate’s state.”

Once an individual has raised or spent more than $5,000, he or she must register with the Federal FEC as a candidate and transfer funds into a campaign account, whose funds will be disclosed. The FEC provides easy-to-navigate definitions for election-related organizations.

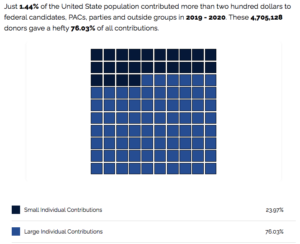

So who does donate? Few Americans actually donate to political campaigns, although the impact is still large. The graphic for 2019-2020 from Open Secrets illustrates:

Political Action Committee (PAC)

PACs are political committees that are “established and administered by corporations, labor unions, membership organizations or trade associations.” As such, they spend money on elections and can donate money to parties or candidates, but are not party-affiliated or an authorized committee of a candidate.

PACs that are established, administered or financially supported by a private sector company or labor organization are called separate segregated funds (SSFs). They are funded by the organization with which they are associated and can only receive contributions from individuals connected to these groups, such as those who work for or own shares in the corporation. Open Secrets keeps track of the top corporate PAC contributors. PACs without such a corporate or labor sponsor are called nonconnected PACs. They are financially independent and are allowed to solicit funds from the public.

Independent Expenditure-Only Committee (Super PAC)

Super PACs “can solicit and spend unlimited sums of money” but “cannot contribute directly to a politician or political party.” This is why they are also called independent expenditure-only committees; independent expenditures (IEs) are made for a communication that advocates for the election or defeat of a clearly identified candidate but is not coordinated with a candidate, candidate’s committee, party committee or their agents.

Super PACs are not legally considered political action committees and are regulated under different rules; for example, PACs can contribute directly to candidates and political parties, but super PACs cannot.

527s

527s are “tax-exempt group[s] organized under section 527 of the Internal Revenue Code to raise money for political activities.” 527 organizations are most commonly used as tools for issue advocacy or to drive voter turnout, and are prohibited from expressly advocating for the election of a specific candidate. They can raise unlimited funds from individuals, labor unions, and corporations, but they must register with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and disclose contributions and expenditures. Registering with and abiding by IRS guidelines, but not organizing as a PAC with the FEC, makes this structure unique among the other political organizations.

501(c)

501(c) is the IRS’s designation in the tax code for most nonprofit groups. 501(c)s account for a small slice of political spending (only 5% in 2012 and 3% in 2016) but are often involved with policy research and/or advocacy, which often inform candidate positions on policy issues.

501(c)(3) organizations are charitable organizations that are “absolutely prohibited from directly or indirectly participating in, or intervening in, any political campaign,” based on IRS code.

501(c)(4) organizations are categorized as “social welfare organizations” and may engage in some political activities as long as they spend less than 50% of their money on politics. 501(c)(4) organizations are unique because they can engage in political spending but are not required to disclose donors.

501(c)(5) organizations are labor unions and 501(c)(6) are trade associations like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. Both operate similarly to 501(c)(4) organizations.

If you are affiliated with a 501(c) organization, here is a helpful guide to navigate the lines of political and non-political activity.

The Role of Government

Federal

The Federal Election Commission (FEC) oversees federal elections. This independent regulatory agency administers and enforces federal campaign finance law, meaning it has jurisdiction over U.S. House, Senate, Presidential and Vice Presidential campaign finance.

Federal campaign finance law focuses on public financing of presidential campaigns, public disclosure of funds raised and contributed to federal political candidates, and limits on such contributions and expenditures.

State

States set their own campaign finance laws, but they must also comply with federal law. For example, some state level laws are set in the state constitution or created through ballot measures, while others borrow from the federal government’s guidelines, and still others create their own approach and experiment from there.

States must also comply with federal Supreme Court decisions as well as court decisions from their local circuit or state. Federal and appeals court precedent applies to all elections, but outside of those rulings, states are able to create their own laws. For example, some states allow corporate contributions to state elections, while such contributions are prohibited in federal elections.

All states have a governing body for campaigns and that oversees state and local elections, either through a State Board of Elections, its office of the Secretary of State, an ethics commission, or another campaign finance-type regulatory body. The National Conference of State Legislators (NCSL) has broken down election laws and campaign contributions limits, and Ballotpedia compares campaign finance laws across the states.

Legislation

Financing campaigns is nothing new; according to the Journal of Legislation at NDL Scholarship, “Simply put, money has always been a part of the American political process.” For example:

- 19th century gubernatorial campaigns in Kentucky solicited contributions ranging from $5,000 to $10,000 (about $150,000 to $300,000 today).

- In the 1896 presidential race, William McKinley is said to have raised and spent between $6 and $7 million dollars (over $200 million today).

- Over one hundred years later, labor unions contributed over $260 million to campaigns in 2020.

This Money In Politics Timeline identifies the first restriction on soliciting campaign contributions as the 1867 Naval Appropriations Bill which “prohibited officers and employees of the federal government from soliciting money for political campaigns from naval yard workers.”

In the early 1900s, “allegations that corporations had exerted outsize influence on prior presidential elections” prompted the passage of the Tillman Act in 1907. After, Congress enacted several more pieces of legislation including the 1910 Federal Corrupt Practice Act, the 1939 Hatch Act, and the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act, all of which established campaign finance limitations, regulations, and disclosure requirements.

The multiple laws proved difficult to enforce since there was no single framework. Congress passed the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 to replace the existing patchwork laws. Congress amended the Act in 1974 to set more limitations on spending and contributions, and to establish the Federal Election Commission, an independent agency to oversee campaign finance.

By the 1990s, “perceived loopholes” in the 1974 Act prompted further reform. Congress enacted in 2002 the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (also called the McCain-Feingold Act) to address issue advocacy (“advertisements that praised or criticized a federal candidate…but did not explicitly call for election or defeat of the candidate.”) and soft money (“funds generally perceived to influence elections but not regulated by campaign finance law.”).

Significant Court Cases

The U.S. Supreme Court has worked to balance concerns about corruption in campaign financing without infringing too broadly on First Amendment rights. “The Supreme Court has consistently held that restrictions on political speech must serve the state’s interest in fighting corruption, or in reducing the appearance of corruption.” This measure is often utilized to prove corrupt quid pro quo exchanges.

Strict scrutiny is the guide used by the Supreme Court when it comes balancing campaign finance restrictions and freedom of speech rights. “Strict scrutiny is the most rigorous form of judicial review… Once a court determines that strict scrutiny must be applied, it is presumed that the law or policy is unconstitutional. The government has the burden of proving that the challenged policy is constitutional. To withstand strict scrutiny, the government must show that its policy is necessary to achieve a compelling state interest. If this is proved, the state must then demonstrate that the legislation is narrowly tailored to achieve the intended result.”

Buckley v. Valeo (1976)

The Federal Elections Campaign Act of 1974 was very broad. Buckley v. Valeo defined what individuals can and cannot do with respect to campaign donations. The Supreme Court ruled that “political campaign spending limits violated the First Amendment” because they ‘“restrict the quantity of campaign speech by individuals, groups and candidates.’”

The Court let stand a federal candidate contribution limit – $1,000 (tied to inflation – today is $2,700) per individual donor per election (counting the primary and general elections separately).

Buckley v. Valeo also struck down a provision of the Federal Election Commission that mandated public financing for presidential elections. With public financing, candidates accept public money and promise to limit how much they receive in private donations and spend on their campaign. Today, there are 14 states that provide some form of public financing for certain elected positions, but since the Buckley v. Valeo decision allowed candidates to opt out, most seek private contributions that do not require them to abide by state spending limits.

Randall v. Sorrell (2006)

“Following the Buckley decision,” explains the Institute for Free Speech, the Court rule in Randall v. Sorrell “that contribution limits ranging from $200-400 per two- year cycle were so low” that they essentially restricted free speech. For a couple of examples, Ohio has a high limit while Colorado, Massachusetts, Connecticut and Montana have very low limits, thus it could be construed that the low limits for contributions restrict the right to express support for candidates, which is a form of speech.

Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010)

The New York Times reports a non-profit group called Citizens United wanted to air a movie during the final weeks before the 2008 Democratic primary election. However, regulations set by the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act “banned the broadcast, cable or satellite transmission of ‘electioneering communications’ paid for by corporations or labor unions from their general funds in the 30 days before a presidential primary and in the 60 days before the general elections.”

The Supreme Court heard the case and struck down the restrictions on political spending by corporations (including nonprofit corporations) and unions. The Supreme Court determined that “across-the-board bans on corporate or union expenditures are unconstitutional.” The federal ban on contributions by foreign nationals, the restriction on contributions to candidates by corporations, and the sponsor disclosure requirements remained law.

The Campaign Finance Institute’s report, “Citizen Funding for Elections,” notes that “political campaigns have always been financed disproportionately by people with above average incomes … But the balance has tilted almost beyond recognition since the Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in Citizen United v. Federal Election Commission … As a result, a number of jurisdictions have been looking recently to rebalance the incentives through new (or updated) citizen funding programs or tax credits to enhance the role of small donors.”

Khan Academy digs into the details of campaign finance and the Citizens United case (9 min):

McCutcheon v. FEC (2014)

This ruling struck down overall limits on federal political contributions. Prior to McCutcheon, there was a direct limit to candidates (as there is now) but also a broad umbrella limit. The courts overturned the broad, aggregate limit.

Chief Justice John Roberts “reaffirmed the federal government’s right to place certain limits on campaign contributions ‘to protect against corruption’” but maintained in the court’s majority opinion, “‘There is no right more basic in our democracy than the right to participate in electing our political leaders…We have made clear that Congress may not regulate contributions simply to reduce the amount of money in politics, or to restrict the political participation of some in order to enhance the relative influence of others.’”

Janus v. AFSCME (2018)

In its ruling in Janus v American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), the Supreme Court ruled “that public sector unions cannot require non-member employees to pay agency fees covering the costs of non-political union activities.” In 2017, unions represented about 40% of the public sector workers, almost 8 million workers. This level of membership gives public sector unions “considerable political influence at the local, state, and federal levels.” The decision supported the argument that requiring members to pay agency fees violated free speech rights and was akin to “compelling them to give financial support to an organization whose political activities they might not support.”

Contributing to Campaigns

Limits and Regulations

You may contribute as much money as you like to a 501(c)(3), (c)(4), (c)(5), or (c)(6), or a super PAC, which conducts independent expenditures. By law, there are no limits on “independent expenditures, or contributions to groups that only make independent expenditures.” If you are contributing directly to a candidate, to a political party, or to a political action committee (PAC), there are limits on the amount you can contribute.

At the federal level, the FEC sets the limit; for state elections, the limit varies by state. In one state-to-state comparison, Alabama allows for unlimited contributions from individuals in State Senate races, State House races and Governor’s races. Alternatively, Wisconsin limits the contribution from an individual to $20,000 for a statewide race, $2,000 for a State Senate race, and $1,000 for a State Assembly race.

Disclosing Donors

As the Institute for Free Speech outlines, “all spending calling for the election or defeat of candidates requires some type of disclosure, and there is more disclosure today than at any previous time in U.S. history.” The FEC requires the entity paying for an ad to be named in broadcast and cable political advertising, as well as print ads. Candidates, political parties, PACs, and super PACs at the federal level and in 49 states must disclose their expenditures, income, and donors. Here is the Open Secrets summary of disclosure rules per organization.

In most situations, when you donate money, you are required to disclose your name, to whom you donated, your address, your occupation, and your employer. That information is held in a public database, and other members of the public (including journalists) may access it. If you contribute to a federal candidate, super PAC, PAC or to a political party organization (like the RNC/DNC), donations over $200 are disclosed.

501(c)(3) and 501(c)(4) organizations are not required to publicly disclose donor information. As noted above, a 501(c)(3) is precluded from doing most political activity, and a 501(c)(4) can only spend 50% of its resources on political activities. 527 organizations are not subject to FEC reporting requirements, but they are subject to IRS reporting.

There is currently a debate as to whether or not nonprofit organizations should be required to disclose donors on their spending. Some argue the lack of transparency serves special interests and contributes to corruption. Others say disclosure requirements could hurt free expression by discouraging participation and donations. When people give to nonprofit organizations, they are not in control of what the organization does. People give because they like the aspects of the organization’s mission, but they are not liable for the organization’s every spending decision.

Try searching the FEC database for a record of contributions, and cross check that with a site like CQmoneyline to identify any donations like those to 527 organizations that weren’t subject to the FEC. Open Secrets also has a donor look up site. The Policy Circle’s Philanthropy and Civic Engagement Brief takes a closer look at donor privacy.

Conclusion

It is up to you to choose how you donate and to whom. Donating is a personal decision and one that can make a difference by making yourself heard. It’s also prudent for you to know the laws if you are donating so you know the information that will be disclosed, and if you are running so you are in compliance.

Thought Leaders and Resources

Institute for Free Speech and its Campaign Finance Sheet for Journalists

Campaign Finance Institute and its State Law Database

Federal Election Commission, its legal-resources, and its Candidate and Committee Guides

National Conference of State Legislature’s Election Resources

Ballotpedia’s Federal Campaign Finance Laws and Regulations and State Laws Map

Campaign Legal Center’s Campaign Finance Resources

Open Secrets Money In Politics Timeline

Ways to Get Involved/What You Can Do

Measure: Find out what your state and district are doing about campaign finance.

- Do you know how campaigns are financed in your community or state?

- What are your state’s laws campaign finance laws?

- Is there a coalition/task force/organization/project on citizen funding in your community?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Who are the members of coalitions, boards, or committees in your state?

- What steps have your state’s/community’s elected/appointed officials taken?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state. Talk to your friends and colleagues.

- Foster collaborative relationships with community organizations, school boards, local businesses.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, communications@thepolicycircle.org, for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policy makers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Search for articles about candidates that interest you.

- Research what groups are supporting each of the candidates. Researching these groups might encourage you to donate to a political organization supporting your cause instead of to the candidate directly, or to contribute to a candidate and also to a philosophically aligned organization.

- Donate – candidates and organizations make it very easy to donate and include the “Donate now” button on their homepage, where you will also see the fine, legal print of how the funds can be legally deployed.

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.