Introduction

View the Executive Summary for this brief.

Strong communities are an essential part of America, but where we live, how we live, and how we interact with each other is changing. The ability to buy everything online, have our groceries delivered straight to our door, and work remotely instead of from an office creates a very different picture of Main Street.

David Bohigian, former acting CEO of the U.S. Overseas Private Investment Corporation (now the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, DFC), looks at sidewalks when he thinks of neighborhoods: “I think the way you judge a neighborhood is by the sidewalks…We talk about capital often, financial capital, but social capital is built on sidewalks.” Sidewalks can offer beauty in the form of well-paved roads and paths around green spaces and central areas; prosperity, as business can grow where there is foot traffic, providing more gathering places that expand opportunities for human connectedness. For more on these three areas of impact in neighborhoods, see Conscious Capitalism.

What else do people today want in their communities? How else are America’s communities and the face of Main Street changing? Is a loss of personal connection through digitization impacting communities? And who plays a role in fixing communities that may be on the decline?

Listen to The Civic Leader Podcast for an audio version of this brief.

Case Study

During a period of urban renewal in the 1950s, manufacturing businesses moved away from the Lower Manhattan industrial district known as SoHo. The lofts the businesses left vacant were attractive to artists as studios and residences, and they were cheap. The only problem was zoning laws, which declared the buildings as non-residential. The SoHo Artists Association worked hard to change the zoning laws: in 1971 the code was amended for artist residency and again in 1986 for open residency.

Today, the SoHo Artists Association’s successor, the SoHo Alliance, continues to work with elected officials and city agencies to control development and preserve the historic district. For 2021, the group, along with other neighborhood stakeholders, became actively involved in rezoning in the neighborhood.

SoHo created the template for “reinventing a faded industrial neighborhood for residents and artists,” and community activists and organizations such as the SoHo Alliance aim to keep it that way. In 2016, the SoHo Alliance helped form a group of local activists, residents, independent realtors, and small business advocates in an all-volunteer, nonprofit called Clean Up SoHo after residents became fed up with litter and overflowing waste on sidewalks. Clean Up SoHo works with the Department of Sanitation, fosters partnerships with community leaders, educates landlords and businesses about their responsibilities under NYC law, and provides options for community outreach.

SoHo created the template for “reinventing a faded industrial neighborhood for residents and artists,” and community activists and organizations such as the SoHo Alliance aim to keep it that way. In 2016, the SoHo Alliance helped form a group of local activists, residents, independent realtors, and small business advocates in an all-volunteer, nonprofit called Clean Up SoHo after residents became fed up with litter and overflowing waste on sidewalks. Clean Up SoHo works with the Department of Sanitation, fosters partnerships with community leaders, educates landlords and businesses about their responsibilities under NYC law, and provides options for community outreach.

Coral Dawson, a member of Clean Up SoHo and founder of Green Below 14, says, “It’s our responsibility as residents who care about our community to raise our valid concerns.” Members agree that cooperation and awareness are essential to making a difference and ensuring the community thrives.

Why It Matters

A community’s well-being is related to that of its residents. A 2018 Harvard study found that, “people who are more socially connected to family, to friends, to community are happier, they’re physically healthier and they live longer than people who are less well connected.” This is not only in terms of physical health and healthcare quality, as geography can often times affect access to care, but also in terms of social community health. For example, Habitat for Humanity homes in Fort Wayne, Indiana, were all built with front porches, giving homeowners the chance to sit outside and interact with neighbors. Residents found themselves living not only in a safe community, but in one that gave them the opportunity to build strong relationships with neighbors and talk to each other, even shoveling each other’s driveways and babysitting. Even the smallest of additions, like a front porch, a park, or a local business, can provide communities with beauty, prosperity, and human connectedness.

Putting it in Context

History

During the 19th and 20th centuries, booming industries and the Industrial Revolution drew workers to cities. During World War II, African Americans and racial minorities migrated north for economic opportunities, further expanding the urban middle and working classes in industrial cities. The result was “middle neighborhoods,” which were “blocks of single-family homes connected by busy arterial streets, with businesses, houses of worship, public schools, and distinct ethnic or racial identities that sustained a social fabric.”

As these houses aged, weak demand and low property values made rebuilding and repopulating the neighborhoods difficult, contributing to “white flight” during the 1960s and 1970s. These urban middle neighborhoods became the focus of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty and an important component of the civil rights movement. A series of violent events in big cities including New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Detroit during the 1960s was met with government community development programs to help create national institutions and financial intermediaries meant to provide local organizations with loans and grants. For more on the role of the Federal Government in America’s housing market, see the Policy Circle’s Housing Brief.

Efforts to revitalize struggling communities in the 1980s and 1990s had mixed results, and many families began migrating to the suburbs during the 2000s. Industrialization originally brought workers and workplaces together; the neighborhood was where people lived in order to work. However, as industrialization brought opportunities for physical mobility through cars and trains, many workers aspired to live “beyond the shadow of the smokestack.” These areas became the suburbs, “living places where one worked to live” and could spend the benefits of work. Soon enough, families flocked to the suburbs as the ability to move away from city centers became a symbol of social and economic success.

The year 2008 marked another economic downturn when subprime lending led to a foreclosure crisis. The subsequent global economic collapse eroded homeownership and property values, making it unprofitable to build new homes and neighborhoods. Although home values have since rebounded, construction has been slow to follow. Many people are having trouble finding neighborhoods in which they can afford to live due to this lack of supply: even a six-figure household income is frequently not enough to purchase a home in the suburbs, leaving many people to live beyond the suburbs, further from central locations with jobs and amenities.

By the Numbers

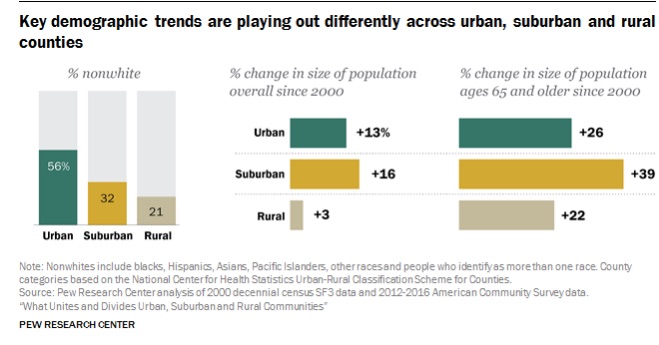

Across the U.S., there are approximately 46 million Americans (15% of the population) living in 1,969 rural counties, 175 million Americans (55%) living in 1,093 suburban counties, and 98 million Americans (31%) living in 68 urban core counties. The population of adults 65 and older has increased the most in the suburbs and immigrants tend to flock to metropolitan and urban areas. Among rural counties, 30% have concentrated poverty, meaning at least 20% of the population is poor. Rural counties also tend to have the smallest share of prime-age workers.

Since 2000, the suburbs have seen large population gains, driven by young adults ages 18-25 and by adults ages 65 and older. Meanwhile, more adults ages 25-44 had been moving to center counties as opposed to the suburbs, although fallout from the coronavirus pandemic shifted this trend more towards less crowded regions. For more on where people have moved during the pandemic, see The Policy Circle’s Migration Between States brief.

The Role of Government

Federal Government

The federal government played an increasingly important role in neighborhoods during the Great Depression through the New Deal’s community development programs. After World War II, however, urban areas in particular drew the government’s attention. The Housing Act of 1949 authorized the government to seize “blighted and slum areas” by eminent domain, demolish the buildings present, and give them to private developers to revitalize.

These government measures drew criticism from activists such as Martin Anderson, who claimed in his book The Federal Bulldozer, “any plan to combat urban ills should involve, or better yet be written by, the people who were the objects of that initiative” so as to have “‘maximum feasible participation’ of the poor in the design and implementation of the government programs that would affect them.”

Government revitalization efforts continued throughout the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, particularly with President Johnson’s War on Poverty and the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964. As part of an amendment to the act called the Special Impact Program, Senator Robert F. Kennedy set up the first Community Development Corporation (CDC) to revitalize communities by providing education, job training, healthcare, commercial development, and affordable housing. In the 1970s, the Federal Home Loan Bank joined the Department of Housing and Urban Development to create Neighborhood Housing Services of America (now called NeighborWorks America) National Community Development System.

Today, larger, more organized CDCs can target federal funding for community development projects in poor urban areas. NeighborWorks America does so by supporting a network of over 240 community development organizations across the country, and frequently works with, reports to, and does research for the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). HUD also supports state and local governments in community development through the Office of Block Grant Assistance. Block Grant programs allow local governments “to address locally identified community development needs” and support activities related to infrastructure, economic development, public facilities, and homeowners and business owner assistance.

HUD received just over $53.7 billion in funding for the 2022 fiscal year. Block Grant programs received $3.5 billion. HUD reports that between 2005 and 2013, Block Grant programs assisted 1.1 million people with homeownership, 33 million people with public improvements, and 105 million people with new public services. However, there is little other evidence of benefits of Block Grant funding, but whether this is due to lack of investment in evaluation methods is unclear. Some argue there is corruption in the program and say that it does not effectively target funding to the populations most in need due to outdated distribution formulas.

State and Local Government

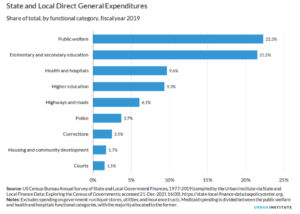

Local governments include county governments, municipalities, townships, school districts, and even water or sewage authorities. According to the most recent data, from 2019, 30.8% of state and local government expenditures went to elementary, secondary, and higher education; 22.4% to public welfare programs such as Medicaid; and 9.6%% to public health and hospitals. Revenue sources include business taxes, sales taxes, and state government transfers. Property taxes tend to be localities’ largest single source of revenue, amounting to almost one-third of revenue in 2019. The Institute for Policy Innovation has also investigated “hidden taxes” taxpayers may be paying at the state or local level that are already calculated into things such as paychecks, gas prices, and licensing fees. Licensing fees, or permitting fees, can be an example of red tape an individual may need to go through in order to establish a business in a community.

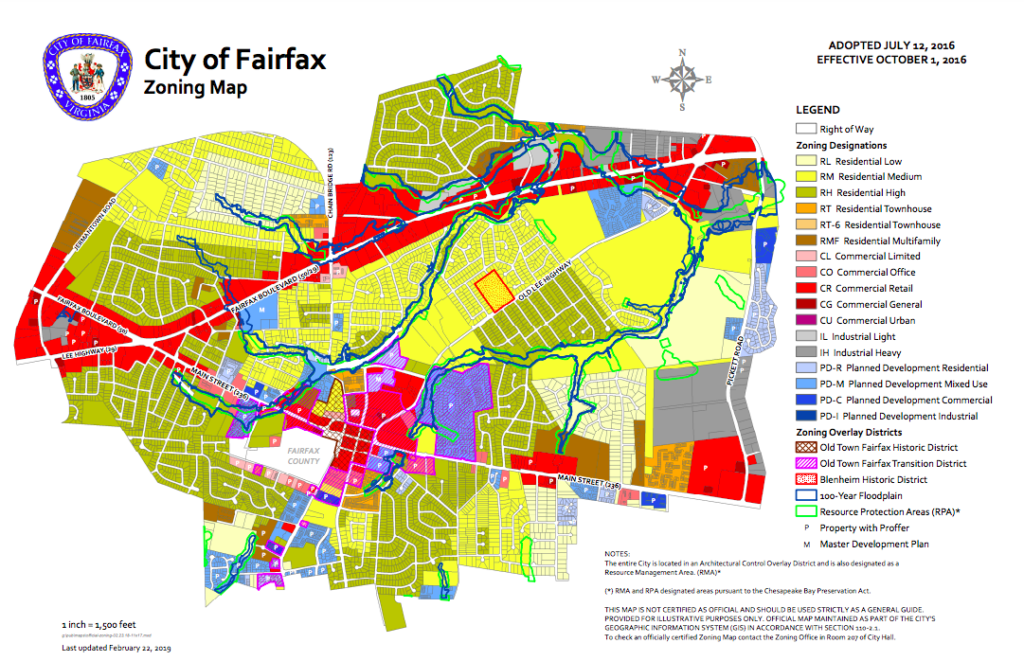

Local government regulations have considerable influence on communities. Zoning, for example, is a “legislative process for dividing land into zones for different uses.” Individual counties, cities, and townships have their own sets of zoning regulations, called ordinances. Even though developers often determine what to build, where they are allowed to build is controlled by local zoning laws, and the “city council is the final decision-maker on all zoning applications.” Essentially, the city council’s decisions on zoning set the rules on everything from the structure of Main Street to whether you can run a business in your house. See more below on zoning.

Despite the importance of local government and the budgets they oversee, hundreds of local government races across the United States see incumbents running without competition. Ballotpedia’s analysis of uncontested elections in 2020 found an average of 40% of local seats were uncontested. Voter participation is another part of the issue; in bigger cities, 15% of elections were uncontested, but only 25% of New York City’s registered voters and only 20% of Los Angeles’ registered voters participated in mayoral races in 2017.

Involving the Private Sector

Agricultural enterprises were the primary forms of small business in the 19th century, but as cities assumed greater economic importance in the 20th century, businesses multiplied. Mom-and-Pop shops opened on Main Street, and many small businesses expanded their scale to fit demand and became large corporations. Senator Robert F. Kennedy was a proponent of “tapping the power and wealth of corporate America for social betterment” as an alternative to big government programs that often failed to involve local community members. Large companies like GE and IBM helped run government programs in a kind of public/private partnership.

Today, AT&T Believes, Quicken Loans’ Rocket Community Fund, and Emerson’s Ferguson Forward program are just three examples of this ongoing role for the private sector. The government-led Opportunity Zones tax incentive program is an example of government incentivizing the private sector to invest in distressed communities. For more on Opportunity Zones, take a look at the Policy Circle’s Creating Career Pathways Brief.

Challenges and Areas for Reform

Small Businesses

Businesses of less than 500 employees are classified as small businesses. Small community businesses have been the lifeblood of neighborhoods since the Industrial Revolution, and communities that create a friendly environment for entrepreneurs open up new ventures, add diversity to the community, and put money back into the local economy. The U.S. Senate Committee on Small Business & Entrepreneurship says small businesses create almost two-thirds of new jobs and employ almost half of the country’s private workforce. According to American Express’ Small Business Economic Impact Study, two-thirds of every dollar spent at a small business stays in the local community, and every dollar spent at a small business creates an additional 50 cents in local business activity. The Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta additionally found small, locally-owned businesses were positively associated with county income, employment growth, and poverty reduction.

At the turn of the century, around 600,000 new businesses opened every year; since the Great Recession from 2007-2009, that number has been cut down to about 400,000. Retail vacancy affects “streetscapes just about everywhere – from north to south, from sea to sea, from urban centers to small towns.” And business owners agree that less competition is not a good thing: more vacancies often results in less overall foot traffic in the area. The New York Times captured how the combination of soaring rents and online shopping has “forced out many beloved mom-and-pop shops.”

The coronavirus pandemic has only exacerbated small business closures; one Yelp analysis indicated almost 100,000 small businesses across the country had closed permanently between March and September 2020. A report from the Federal Reserve determined “around 200,000 more U.S. businesses permanently closed as a result of the pandemic than in a typical year.” The federal Paycheck Protection Program was intended to keep small businesses afloat, but longer term solutions may require more investment in “infrastructure and services that will support our future generations of entrepreneurs.”

These are the kinds of resources that can connect entrepreneurs to the community. A study by the Chicago Federal Reserve supports this idea: the study found the “success of small businesses in any neighborhood is linked…to the extent to which businesses are connected to their regional economies” and recommends investing in areas such as education or labor-force preparedness to assist and better integrate small businesses into neighborhoods, particularly in lower-income areas.

Small Business Saturday is one popular effort to bring attention to entrepreneurs. Started by American Express in 2010, Small Business Saturday takes place on the Saturday after Thanksgiving, between Black Friday and Cyber Monday. It focuses on “business associations, state and local chambers of commerce, small businesses, and other community organizers” and seeks to “encourage Americans to shop at local retailers.”

See the U.S. Small Business Administration’s 2021 Small Business Profile here.

Digital Effects

Reports show that many small business owners are not fazed by technology and shifts to online retail. In 2018, a Wells Fargo/Gallup Small Business Index found almost ⅔ of the 604 small business owners surveyed said their companies have the necessary technology to be competitive in their industries. In fact, as early as 2012, the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Report found over half of U.S. businesses start and operate at home, and 75% of home-based businesses have employees, but work is done virtually rather than in a physical workspace.

The efforts pay off; according to a Deloitte report, relative to businesses that have low levels of digital engagement, digitally advanced small businesses earned twice as much revenue per employee, were almost three times as likely to be creating jobs over the previous year, and had an average employment growth rate that was more than six times as high.

Most small business owners were capitalizing on technology and Internet connections even before the coronavirus pandemic, which has forced businesses that “have long earned their keep through brick-and-mortar operations” to turn to e-commerce. Expanding online presence allowed businesses to diversify their revenue streams, keep staff employed, and expand their audience of potential customers.

Community Technology and News Deserts

Many neighborhood apps combine the physical with digital. Nextdoor is an app that markets itself as “the world’s largest social network for the neighborhood,” and Amazon’s Ring Neighbors app “is more than an app, it’s the power of your community coming together to keep you safe and informed.” In fact, such apps have stepped in to fill the void left behind by the loss of local newspapers over the past few decades, which has led to local news deserts: “areas that no longer have reporters to cover goings-on that aren’t on a national scale.”

Penny Abernathy, chair of journalism and digital media economics at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, notes that newspapers “are often the prime, if not the sole source of news and information, especially in small and mid-sized communities.” However, “news deserts” have been on the rise in the last 15 years; 1,800 newspapers have disappeared, and those that continue printing have lost more than half of their journalists. In Tennessee, the Tennessean bought the Nashville Banner, but only kept 70 of the Banner’s 180 journalists. This means “large swathes of what was once covered, of courts, of institutions, of major kinds of stories just don’t get covered.”

In recent years, public radio stations have increased focus and spending on local journalism, and some board members of the taxpayer-supported Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) have called for requiring nationwide television and radio networks to spend more on local community reporting. Alternative newspaper business models are another option. One membership model seeks public contributions for journalism; a similar model relies on foundations and philanthropies for funding, although this model has been judged for lack of political neutrality. Local activists and “citizen journalists” have the ability to write about information of interest in communities, but are “no substitute for professional journalism.”

Some analysts also advocate targeting social media, as they believe these outlets further damage the news industry. Many newspaper stories are posted on Google and Facebook, but these companies benefit from advertising revenue, not the newspapers. This may be changing; in early 2021, Google and Facebook started looking at striking deals with media companies that would require them to pay news outlets for content.

Do you live in a news desert? Find out with this map from the University of North Carolina Hussman School of Journalism and Media.

Tax Incentives: The Amazon Effect

Amazon tends to be the first thought when people discuss the trend of online shopping, as it ushered in “the age of e-commerce and two-day delivery.” Still, some argue Amazon is not “crushing the hopes and dreams of every mom-and-pop shop in America,” but rather is “changing the way small business owners sell their products.” Amazon claims about half of the items it sells are produced by small- and medium-sized businesses.

Amazon demonstrated its power and influence through the bidding process as it searched for a second headquarters location in 2018. More than 200 North American cities submitted bids, hoping to persuade Amazon with “tax exemptions, abatements, regulatory relief, and taxpayer assistance.” In Arlington, Virginia, where Amazon decided to build a headquarters location, the county board voted unanimously to grant Amazon “an estimated $51 million incentive package that includes $23 million in cash over 15 years as well as a $28 million, 10-year investment for infrastructure and open space.”

In New York, where harsh opposition prompted Amazon to back out of building its headquarters in Queens, the company would have received “up to $1.4 billion in tax breaks through the Relocation and Employment Assistance Program,” which would have cost the city an estimated $33 million in lost revenue, as well as $268 million through the Industrial and Commercial Abatement Program, which would have cost the city another $198 million in lost revenue. Supporters of the plan argued that the 50,000 Amazon workers earning an annual average wage of $150,000 would have brought a large boost of tax revenue, and that “the majority of the tax breaks and grants Amazon would have received were contingent on the company fulfilling its promises regarding hiring and occupying commercial real estate.”

For decades, incentive packages have been used “predominantly to attract manufacturers with lots of employees and capital investment.” Many economists see tax incentives as “corporate giveaways that divert money from education, infrastructure and other priorities that ultimately do more for a region’s economy.” Economists also note the vast majority of tax incentives go to large, established companies, not to local start-ups or community businesses. Politicians in New Jersey have started to change their state laws by scaling down their ability to make big promises and raising oversight standards for their tax incentive programs. In Michigan, lessons learned from past failed bids, like the Foxconn deal that went to Wisconsin and has since run into timing and delivery challenges, shape the way they are attracting businesses today.

For more on these kinds of economic incentive packages, see The Policy Circle’s Government Transparency & Accountability brief.

Social Infrastructure

While neighborhoods change, tried and true institutions continue to provide community benefits. For example, an American Time Use Survey found “spending a few hours at church per week had a huge impact on life satisfaction.” Libraries, parks, religious institutions, and other “physical places that allow bonds to develop” are called social infrastructure. These institutions “provide meeting grounds, they provide modeling and mentoring, and they provide meaning and purpose,” without which people risk isolation, alienation, and well-being.

According to the American Community Life Survey released in 2021, Americans with access to neighborhood amenities, whether they are commercial spaces (ex: bars, restaurants, and coffee shops) or public spaces (ex: parks, libraries, and community centers) benefit greatly. Those with local neighborhood spots report feeling more closely connected to their neighborhoods and those who live in their communities. Likewise, those who live close to neighborhood amenities, report increased feelings of safety and social trust.

Investment in social infrastructure “is becoming a key part of placemaking and urban policy” and there are many different kinds of policy projects that can invest in social infrastructure. For example, public art can “spark revitalization in blighted neighborhoods and turn vacant land into places where people want to live, work, and play.” In New York City, an old abandoned piece of transit infrastructure was turned into a park area which is now the High Line, one of the city’s largest tourist attractions. Similarly, “green infrastructure,” such as parks or community gardens, provides excellent gathering places for recreational activities, community engagement, and health. Schools and libraries, beyond serving educational purposes, are institutions through which community members – particularly children and even immigrants – are able to develop bonds and contribute to the community. Religious institutions, beyond being houses of worship, can “build communities and become institutions of civil society,” as well “provide the safety net and sense of purpose that only tight-knit communities can provide.”

Physical spaces are not the only way to provide social cohesion; festivals and special events can provide communities with extra benefits. During these events, local vendors, artisans, restauranteurs, and hoteliers all benefit from visitors, which contributes to quality of life by strengthening communities, providing unique activities and events, building awareness of diverse cultures and identities, and acting as a source of community pride.

Focusing on inclusivity and providing the opportunity to form human connections is key: “Connections are the ‘glue’ that hold communities together; without them, a community stagnates and the quality of life declines.” Social infrastructure is “less a thing to maximize than a lens that communities and policymakers should apply to every routine decision about physical investment.” For example, Design Center is a Pittsburgh-based nonprofit provides design services and technical support for residents who want to improve their neighborhoods.

Zoning

When it comes to building the actual locations of social infrastructure, zoning laws play an important role as they regulate the use of land and structures built upon it. Zoning ordinances, determined by local government, divide cities into districts, such as commercial, residential, or historic districts.

By controlling what can be built in a particular district, zoning affects where people can live. Not all land can be used for residential purposes, which creates artificial scarcity that increase the cost of land. The gap between what land would cost if there were no regulations inhibiting development within a city, and the price people actually pay for it, is called economic rent. In the 1990s, sale prices were on average 33% higher than construction costs; by 2013, they were almost 60% higher. In this manner, zoning laws prevent Americans from living close to their work or moving to cities with more jobs.

Other concerns include gentrification, when an “influx of higher-income residents to impoverished areas can ‘displace renters and homeowners, jeopardize work practices, disrupt family life, and undermine cultural connections'” as rents rise. However, gentrification is also related to large decreases in aggregate neighborhood poverty rates; increases in employment, median incomes, and poverty; and reductions in childhood exposure to poverty as well as improved education attainment rates for children.

The University of Chicago’s Chang-Tai Hsieh and the University of California’s Enrico Moretti estimated that local regulations, which have grown by 50% over the past 50 years, have dampened the U.S. economy as a whole by 9%. Overly stringent housing regulations, particularly in high-wage cities, have resulted in a $1.4 trillion loss in GDP – essentially the equivalent of New York’s GDP. Cutting back on regulations, streamlining permitting processes, changing zoning laws, and investing in regional infrastructure could foster conditions that would make it possible for people to find affordable housing where they can find jobs.

Another common method for cities such as San Francisco, Washington, D.C., and New York City is inclusionary zoning, a “way to produce affordable housing through the private market.” Through inclusionary zoning, private developers are required or incentivized to “designate a certain percentage of the units in a given project as below market rate (BMR)” and make the price of the units based on the area median income. City governments favor this method of maintaining affordability, as little public subsidy is necessary. However, how much cities can demand from private developers is contested, and whether or not these policies can produce a significant number of units to fit the growing need for affordable housing remains to be seen.

The Policy Circle’s Housing Brief goes into more detail on zoning.

Conclusion

With the influx of new technologies and economic developments, our communities will continue to change. From policymakers at the local, state, and national level, to private business owners and community members, we all play a role in determining the future of our neighborhoods.

There are many way in which citizens can easily step into roles of leadership in their neighborhoods. In New York, for example, the Edgemont Community Council was created to serve as the focal point for the community’s active neighborhood-oriented civic associations, giving residents both a community-wide forum for discussions and a non-partisan representative voice at Town Hall. The Council has representation from ten neighborhood associations and nominates non-partisan School District Board candidates, makes beautification, zoning and permitting decisions, and recognizes annual citizens for their outstanding engagement.

Neighborhood Associations are key to thriving communities. In Nashville, the Whitland Area Neighborhood Association hosts an annual July 4th celebration with canoes filled with ice and refreshments, a local orchestra or band to lead All-American sing-alongs, a children’s bike parade, and a bake-off. In the same area, the Richland-West End Neighborhood Association hosts a Halloween extravaganza that usually attracts 1,500 individual trick-or-treaters in three hours’ time and includes a display of 200 Jack-o-lanterns.

History has shown us how neighborhoods have grown, developed, and changed naturally over time through community engagement and government intervention. We need to be thoughtful about our neighborhoods, and consider how local government, businesses, and everyday engagement stitches together the fabric of our communities. We need to look for opportunities to supply our communities with beauty, prosperity, and human connectedness. Calling on neighbors, planting a community garden, or organizing a local businesses happy hour can have a big impact. These actions, though small, make differences in communities, which in turn can make a difference in the world.

Ways to Get Involved/What Can You Do

Measure: Find out what your state and district are doing about economic development and social infrastructure.

- Do you know the state of social infrastructure in your community or state?

- What are your state’s or municipality’s zoning laws?

- Is there a neighborhood association, or does one need to be formed?

Identify: Who are the influencers in your state, county, or community? Learn about their priorities and consider how to contact them, including elected officials, attorneys general, law enforcement, boards of education, city councils, journalists, media outlets, community organizations, and local businesses.

- Who are the members of the Community Development office in your area?

- Who are contacts at your local Chamber of Commerce?

- What steps have your state’s or community’s elected and appointed officials taken?

Reach out: You are a catalyst. Finding a common cause is a great opportunity to develop relationships with people who may be outside of your immediate network. All it takes is a small team of two or three people to set a path for real improvement. The Policy Circle is your platform to convene with experts you want to hear from.

- Find allies in your community or in nearby towns and elsewhere in the state.

- Foster collaborative relationships with community organizations, school boards, public libraries, and local businesses.

Plan: Set some milestones based on your state’s legislative calendar.

- Don’t hesitate to contact The Policy Circle team, communications@thepolicycircle.org, for connections to the broader network, advice, insights on how to build rapport with policy makers and establish yourself as a civic leader.

Execute: Give it your best shot. You can:

- Talk to your local business owners and entrepreneurs to gain insights about the operations of small businesses.

- Are there ways local businesses can form partnerships with others in your area, such as mentorship programs connected to schools?

- Find out from local real estate and economic developers what challenges they face with zoning laws.

- Engage with your local neighborhood association or other community organizations.

- Observe the social infrastructure of your local areas – what does main street look like? Where is the nearest library, and what services does it provide?

- Explore local election statistics and see the status of voter turnout in your local elections.

Working with others, you may create something great for your community. Here are some tools to learn how to contact your representatives and write an op-ed.

Thought Leaders & Additional Resources

Notable Organizations

- Aspen Institute: Weave, the Social Fabric Initiative to “spread the values of a cultural revolution that replaces hyper-individualism with relationism.”

- Nextdoor, the “World’s largest social network for the neighborhood,” which supports more than 200,000 neighborhoods in the U.S., UK, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Italy, Spain, and Australia. NextDoor depends on NextDoor leaders who act as moderators – this could be a potential role for circle members.

- Empower LA, Los Angeles’ Department of Neighborhood Empowerment through which its neighborhood councils “advocate directly for real change in their communities” and consist of residents, business owners, property owners

- mySidewalk, “a city intelligence tool that makes it easy for analysts in local government to measure performance, make sense of the results, and deliver a compelling narrative to policymakers and the public,” helping cities engage with their constituents for positive social change.

- American Enterprise Institute, a public policy think tank championing democracy and human dignity, free enterprise and entrepreneurship, and human potential; and Manhattan Institute, a think tank that aims to foster greater economic choice and individual responsibility.

Private Sector Engagement

- Since 2014, JPMorgan Chase, the largest bank in Detroit, has been helping revitalize Detroit’s local real estate and small businesses by working with residents, local government, and local nonprofits.

- Salesforce has made revitalizing the San Francisco Bay Area its mission, including getting technology into San Francisco and Oakland schools and donating nearly $70 million and hundreds of hours of volunteer work by employees.

- Humana is working with community-based organizations, businesses, and government leaders from Jacksonville, Florida to Kansas City, Missouri, to improve community health by tackling problems including food insecurity and social isolation.

- Enterprise Holdings, Inc. has partnered with the National Park Foundation to support its recreational, educational, and service programs that advocate for healthy lifestyles, as well as with Project Backboard, a local organization in St. Louis that revitalizes public basketball courts for community use, wellness, and beautification.

Suggestions for your Next Conversation

Explore the Series

This brief is part of a series of recommended conversations designed for circle's wishing to pursue a specific focus for the year. Each series recommends "5" briefs to provide a year of conversations.

Deep Dives

Want to dive deeper on Stitching the Fabric of Neighborhoods? Consider exploring the following: